Administer a tetanus booster to all burn victims who are not with current tetanus immunization.2

Pain control should focus on both an around-the-clock regimen, as well as a rescue medication before dressing changes and during increased physical activity.2

• Pregabalin or Gabapentin have been shown to be equivalent or superior to antihistamines for post-burn pruritis in preliminary studies.6–8

Surgery

Full-thickness burns >2 cm usually require skin grafting. Timing of the procedure is crucial: Skin grafting begun within 72 hours is beneficial for non-scald burns in children and adults younger than 30 years old. Observe all other non-scald full-thickness burns for 8 to 10 days. Wait 2 weeks before performing surgery in children with hot water scald burns; earlier interventions in this group have resulted in worse outcomes.9,10

Nonoperative

Airway management is critical in patients with major burns. Intubation should not be delayed if severe inhalation injury or respiratory distress is present or anticipated.

Prevention of shock using aggressive fluid resuscitation is crucial in those with ≥15% TBSA or in major burns. However, over resuscitation can also result in significant morbidity and mortality.

• In adults, initially give IV crystalloid solution, standard of care being lactated Ringer’s. Major burns should be treated with two large bore IVs preferably placed in nonburned skin. The Parkland formula estimates the rate of fluids for the first 24 hours at 4 mL per kg body weight for each % TBSA effected. One half of this total amount should be given over the first 8 hours, with the remainder given over the next 16 hours.

• Maintenance fluids can continue after the first 24 hours with additional boluses titrated to maintain urinary output of at least 5 mL per kg (1 mL per kg for electrical injuries). Poor urinary output is correlated with higher mortality. After the first 24 hours, the crystalloid solution can be changed to 5% dextrose in 0.45% normal saline with 20 mEq of potassium chloride.

• In children weighing <25 kg, maintain hourly urine output at 1 mL per kg.

• The use of colloids (e.g., albumin) appears to offer no advantage over the use of crystalloids.5,11,12

Remove ruptured blisters. Intact blisters should be left undisturbed unless there are signs of infection. If blisters persist without resorption past 2 weeks, refer to a surgeon as there could be an underlying deep partial burn warranting grafting. Avoid needle aspiration of blisters.13

Special Therapy

Dressings. Superficial burns do not require wound dressings. Simple skin lubricants (e.g., aloe vera cream) are sufficient. All partial- and full-thickness burns should have dressings.

• First, gently clean the burn with mild soap and water. Skin disinfectants (Hibiclens, Betadine) can actually inhibit the healing process and are discouraged. Apply a thin layer of topical 1% silver sulfadine or other antimicrobial. Then, cover with fine-mesh gauze (e.g., Telfa) and secure in place with a moderate degree of pressure.

• Change dressings whenever they become soaked with excessive exudates or other fluids. Wound should be cleansed before each redressing.

• Deep wounds may require biologic dressings or skin grafts.14,15

After epithelialization occurs, use an unscented moisturizing cream such as Cetaphil or Eucerin until natural lubricating mechanisms return. Avoid the use of preparations high in lanolin. Evidence for the efficacy of vitamin E lotions is limited.16

Referrals

Refer minor burn patients to a surgeon with burn care expertise if a full-thickness burn >2 cm is discovered or at 2 weeks if wound epithelialization has not begun. Wound complications can also be the grounds for referral. Full-thickness burns <2 cm in diameter can be allowed to heal by contracture when it is in a nonfunctional, noncosmetic area and the skin is not thin.

Follow-Up

See patients the day after injury to adjust pain medications and assess dressing change competence. In the right patient, visits can then be weekly until wound epithelialization occurs. More frequent follow-up is required if there is insufficient pain control, any concern about the patient or family’s ability to provide care, or if synthetic or biologic dressings have been used.

Complications

• All suspected burn infections warrant aggressive management to include admission and parenteral antibiotics. Burn infections are prone to sepsis and will extend the depth and extent of the burn. Diagnosing infection in burn patients is challenging. It should be suspected whenever increasing erythema, edema, pain, or tenderness is associated with lymphangitis, fever, malaise, or anorexia.

• Necrotic tissue in deep burn wounds may cause progressive tissue injury as well as increasing the risk for infection. Wound excision and grafting is usually beneficial.

• Hypertrophic scarring is usually inevitable whenever epithelialization takes longer than 2 weeks in African Americans and in young children, and 3 weeks in all others. Early application of pressure is recommended. Refer patients promptly if the wound misses its epithelialization milestone or if hypertrophic scarring appears.17

• Increased mortality is associated with age >60 years, nonsuperficial burns covering >40% TBSA, coexisting trauma, pneumonia, and, in one study, female sex.18,19

REFERENCES

1. Deitch EA. The management of burns. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1249–1253.

2. Waitzman AA, Neligan PC. How to manage burns in primary care. Can Fam Physician 1993;39:2394–2400.

3. Pushkar NS, Sandorminsky BP. Cold treatment of burns. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1982;9:101–110.

4. Miller K, Chang A. Acute inhalation injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:533–537.

5. Monafo WW. Current concepts: initial management of burns. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1581–1586.

6. Ahuja RB, Gupta GK. A four arm, double blind, randomized and placebo controlled study of pregabalin in the management of post-burn pruritus. Burns 2013;39(1):24–29.

7. Ahuja RB, Gupta R, Gupta G, et al. A comparative analysis of cetirizine, gabapentin and their combination in the relief of post-burn pruritis. Burns 2011;37(2):203–207.

8. Gray P, Kirby J, Smith MT, et al. Pregabalin in severe burn injury pain: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2011;152(6):1279–1288.

9. Baxter CR. Management of burn wounds. Dermatol Clin 1993;11:709–714.

10. Desai MH, Rutan RL, Herndon DN. Conservative treatment of scald burns is superior to early excision. J Burn Care Rehabil 1991;12:482–484.

11. Alderson P, Schierhout G, Roberts I, et al. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;2:CD000567.

12. Muller MJ, Herndon DN. The challenge of burns. Lancet 1994;343:216–220.

13. Rockwell WB, Ehrlich HP. Should burn blister fluid be evacuated? J Burn Care Rehabil 1990;11:93–95.

14. Hartford CE. Care of outpatient burns. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996:71–80.

15. Mertens DM, Jenkins ME, Warden GD. Outpatient burn management. Nurs Clin North Am 1997;32:343.

16. Barbosa E, Faintuch J, Machado Moreira EA, et al. Supplementation of vitamin E, vitamin C, and zinc attenuates oxidative stress in burned children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Burn Care Res 2009;30(5):859–866.

17. Deitch EA, Wheelahan TM, Rose MP, et al. Hypertrophic burn scars: analysis of variables. J Trauma 1983;23:895–898.

18. McGwin G Jr, George RL, Cross JM, et al. Improving the ability to predict mortality among burn patients. Burns 2008;34(3):320–327.

19. Moore EC, Pilcher DV, Bailey MJ, et al. The Burns Evaluation and Mortality Study (BEAMS): predicting deaths in Australian and New Zealand burn patients admitted to intensive care with burns. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;75(2):298–303.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ulmer JF. Burn pain management: a guideline-based approach. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998;19:151–159.

| Smoke Inhalation and Carbon Monoxide Poisoning |

SMOKE INHALATION

General Principles

The inhalation of heated gas and the products of combustion can cause serious respiratory injury and is responsible for the majority of fire deaths, more so than surface burns and their complications. Any patient with carbon deposits in the mouth, singeing of nasal hair, or other findings suspicious for significant smoke inhalation should be admitted to the hospital for observation, treatment, and possible intubation. Approximately one-third of patients admitted to burn units have smoke inhalation as a compounding complication. Hypoxia, heat, and chemicals can all injure lung parenchyma.

Pathophysiology/Etiology

• Impaired tissue oxygenation results from the carbon monoxide and—with increased frequency—cyanide found in smoke. It can be immediately life-threatening.

• Carbon monoxide (CO) accounts for over half of the fatalities in smoke inhalation (see “Carbon Monoxide Poisoning”).

• Suspect cyanide, which impairs cellular oxidative metabolism, when plastics or organic chemicals are fuels,1 especially with high-temperature and low-oxygen settings.

• Thermal injury results from the inhalation of heated gases.

• The supraglottic mucosa, which has little protection from heated gases, often develops edema and subsequent airway obstruction within 18 to 24 hours after exposure.

• The subglottic tissues are generally protected from thermal injury because smoke is dry with a low specific heat and the upper airway has excellent heat exchange properties, although steam inhalation can result in tracheobronchial burns.

• Elective intubation needs to be considered early in all patients with suspected thermal injury.

• Chemical injury is primarily caused by insoluble irritant gases that affect the lower airways.

• Insoluble irritant gases include aldehydes, amines, chlorine, hydrochloric acid, and sulfur dioxide.

• As with thermal injury, there may be a delay between exposure and clinical manifestation.

Diagnosis of Smoke Inhalation

History

• Positive predictive factors for significant smoke inhalation include unconsciousness, entrapment in an enclosed space, and exposure to known toxins.2

Physical Examination

• Facial burns, singeing of eyebrows and nasal vibrissae, carbonaceous sputum, and oropharyngeal carbon deposits are suggestive of inhalation injury.

• Cyanosis, tachypnea, stridor, wheezing, and crackles are suggestive of the need for aggressive treatment; however, these signs are infrequently found despite the presence of significant injury.

Laboratory Studies

• Carboxyhemoglobin testing should be carried out on all patients. Elevated levels (>2%) should raise suspicion regarding the presence of other toxins (e.g., CO and cyanide).

• Arterial blood gases. Hypoxemia and elevated alveolar–arterial (PAO2–PaO2 >15 mm) gradient are frequently seen in inhalation injury, although they are insensitive indicators of injury and do not predict clinical outcome.

• Pulse oximetry can also be used as a noninvasive measure of oxygenation,1 but may be normal despite the presence of carboxyhemoglobin as CO displaces oxygen from hemoglobin but does not change the concentration of oxygen dissolved in the blood.

Imaging

• Chest radiography generally is an insensitive initial test and should be reserved for hospitalized patients and those with suspected thoracic injury.

Diagnostic Procedures

• Bronchoscopy with direct fiberoptic visualization of the upper and lower airway provides an assessment of the extent of injury. Since the appearance of the subglottic tissues is an unreliable predictor of the need for ventilation, laryngoscopy may suffice for management decisions.3

Treatment

Protocol

• Immediate. Early mortality occurs from asphyxiation due to CO and cyanide.

• Remove patient from offending environment.

• Provide 100% oxygen via a non-rebreathing mask until carboxyhemoglobin level is in the normal range. Maintain a partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) greater than 75.

• If cyanide poisoning is present, induce methemoglobinemia. This can be expedited by contacting the local poison control center.

• Early. Upper airway obstruction causing fatal injury occurs in the first 8 to 48 hours after exposure.

• Endotracheal intubation should be strongly considered on initial assessment if physical findings are suggestive of inhalation injury.2

• If direct visualization of the upper airway with laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy reveals even minimal early swelling or obstruction, endotracheal intubation should be performed because swelling will continue for the first 24 hours.

• Bronchoscopy within the first 24 hours can remove foreign particles that may worsen the inflammatory reaction and may decrease time spent in the intensive care unit.1

• Humidified oxygen or air should be given to thin the viscous bronchorrhea that is produced by injured airways.

• Bronchodilators (albuterol 5% solution, 0.5 mL) may have variable effects, depending on whether obstruction is due to edema or bronchospasm. There is no contraindication to its use in smoke inhalation.

• Steroids and prophylactic antibiotics are contraindicated.

• Antibiotics are indicated for proven infection, which tends to occur with the onset of bronchorrhea 2 to 3 days after the injury.

• Late. Adult respiratory distress syndrome is a late complication.

CARBON MONOXIDE POISONING

General Principles

CO, which causes up to 80% of fatalities from smoke inhalation, is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, nonirritating gas produced by incomplete combustion of carbonaceous materials. It is responsible for 500 accidental and 5,000 suicidal deaths in the United States every year. The CO molecule has 240 times the affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin. Toxic effects are due to tissue hypoxia as carboxyhemoglobin is incapable of carrying oxygen and interferes with oxygen release.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

Although exposure levels do not consistently correlate with carboxyhemoglobin levels and symptoms, the following associations are commonly seen:

• Mild exposure (1% to 15% carboxyhemoglobin) causes headache, dizziness, and nausea.

• Moderate exposure (16% to 40% carboxyhemoglobin) causes severe headache, nausea, vomiting, loss of coordination, and unconsciousness.

• Severe exposure (40% to 60% or greater carboxyhemoglobin) causes seizures, coma, and death.3

History

History may include suicidal or accidental exposure to auto exhaust, smoke inhalation, or exposure to a poorly vented heater or appliance.

Laboratory Findings

• Increased carboxyhemoglobin level. Normal levels are 1% to 3%; levels in smokers are 5% to 6%.

• Patients may have a normal arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2).

• Pulse oximetry should be considered unreliable; it cannot differentiate oxyhemoglobin from carboxyhemoglobin.

Management

Medications

• Remove the patient from exposure, maintain vital functions, and support ventilation artificially if necessary. Patient should remain quiet so as to decrease oxygen consumption.

• Administer 100% oxygen until carboxyhemoglobin is less than 5%; 40% to 50% of the body’s CO can be eliminated in 1 hour with high-dose oxygen.

Special Therapy

• Hyperbaric oxygen can reduce the half-life of CO to 22 minutes, although it cannot be routinely recommended due to equivocal trials.1,4 Despite unproven benefit, it can be considered for severe cases, including CO >40%, loss of consciousness, severe metabolic acidosis (pH <7.1), and end-organ ischemia. Because of the increased binding of CO to fetal hemoglobin, consider hyperbaric oxygen for CO >20% in the pregnant patient.

• Consider transfusion of blood or packed cells to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

• Cerebral edema should be managed with diuretics and steroids.

Follow-Up

Monitor the patient after severe exposure for the following neurologic symptoms: tremors, mental deterioration, and psychotic behavior.

REFERENCES

2. Dries DJ, Endorf FW. Inhalation injury: epidemiology, pathology, treatment strategies. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:31.

3. Committee on Trauma. Thermal injuries. In: ATLS manual, 9th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012:230–235.

4. American Burn Association. Inhalation injury: diagnosis. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:307–312.

5. Buckley NA, Juurlink DN, Isbister G, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for carbon monoxide poisoning. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;4:CD002041.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as “a pattern of behavior used to establish power and control over another person through fear and intimidation, often including the threat or use of violence.”1 It is described as assaultive and coercive behavior to include physical injury, psychological abuse, sexual assault, enforced social isolation, stalking, deprivation, intimidation, and threats. A woman’s lifetime risk for abuse is 23%.2 Nearly 5.3 million incidents occur each year among women 18 years of age and older and 3.2 million occur among men.3 Thirty-one percent of women and 26% of men report some form of IPV in their life. These numbers are likely lower than the actual rates due to underreporting of such actions.2 IPV occurs in same-sex relationships as well with 22% to 46% of all gays and lesbians reporting having been in a physically violent same-sex relationship.4

Domestic violence is not a disease present in the body; rather it is a health-related risk factor.5 It leads to adverse health outcomes such as sexually transmitted infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, unintended pregnancy, chronic pain, neurological disorders, gastrointestinal disorders, migraines, as well as other disabilities. Abuse is a common and complex public health issue. Costs of IPV from direct medical and mental health services are estimated to be around $4.1 billion, with total costs exceeding $5.8 billion annually.6 A public health approach seeks to identify a combination of individual, relational, community, and societal factors that contribute to the risk of being a victim or perpetrator of domestic violence.5 Awareness of the prevalence and effects of IPV in all sectors will assist family physicians in addressing this important health issue effectively.

DIAGNOSIS

The CDC has identified several risk factors and signs and symptoms for IPV, and they are outlined in Table 20.4-1. Many risk factors for both victimization and perpetration are the same. Physicians should be aware that those who are identified as at risk may not be involved in IPV.7

As of 2013, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends clinicians screen all women of childbearing age for IPV, to include those that have no signs or symptoms of domestic violence. Those that screen positive should be provided or referred for intervention. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as well as the American Medical Association (AMA) recommend routine inquiry about IPV with all patients.2 The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) notes it is imperative family physicians be aware of the prevalence of violence in all sectors of society, be alert for its effects in their encounters with virtually every patient, and be capable of providing an appropriate response when these issues are identified. With this awareness, physicians are able to work to prevent violence for patients who are at risk within their practices and communities.4

Several screening tools are adequate for identifying IPV in the primary care setting. The Hurt, Insult, Threat, Scream (HITS); Ongoing Abuse Screen/Ongoing Violence Assessment Tool (OAS/OVAT); Slapped, Threatened and Throw (STaT); Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, Kick (HARK); and Woman Abuse Screen Tool (WAST) have the highest sensitivity and specificity and many can be self-administered.

TREATMENT

For patients exposed to IPV, the SOS-DoC framework can aid physicians in responding to these situations.6

• S—offer Support and assess Safety: Keep the discussion private and confidential. Ask questions regarding severity and frequency of violence and safety of others in the household.

• O—discuss Options: safety plans, legal options and community resources.

• S—validate the patient’s Strength.

• Do—Document observations, assessment and plans including safety plans.

Domestic Violence Risk Factors |

Risk type | Victimization | Perpetration |

Individual | Prior history Being female Young age Heavy alcohol/drug use High-risk sexual behavior Being less educated Unemployment For men: different ethnicity from partners For women: greater education than their partners Verbally abusive, jealous, or possessive partner | Victim of physical/psychologic abuse (strongest predictor) Low self-esteem Low income Low academic achievement Heavy alcohol/drug use Depression Anger/hostility Personality disorders Few friends/social isolation Economic stress Belief in strict gender roles Desire for power/control Involvement in aggressive behavior |

Relational | Couples with income, educational, or job status disparities Dominance and control of the relationship by one partner over the other | Marital conflict Marital instability Dominance and control of the relationship by one partner over the other Economic stress Unhealthy family relationships and interactions |

Community | Poverty Low social capital Weak community sanctions against domestic violence | Poverty Low social capital Weak community sanctions against domestic violence |

Societal | Traditional gender norms | Traditional gender norms |

| ||

Associated signs and symptoms with intimate partner violence | ||

Acute injuries | Psychologic | Nonspecific |

Multiple bruises/anatomical sites involved Mechanism inconsistent with findings Firearm wounds Knife wounds Fractures Delay in seeking care | Acute/chronic anxiety Depression Posttraumatic stress disorder Suicidal ideation Sleep disturbance Substance abuse Social isolation | Abdominal/chest/pelvic pain Headaches Insomnia/fatigue Sexual dysfunction Chronic pain Missed appointments |

• C—offer Continuity, follow-up appointments and identify barriers to access.

• In the case of an injury. Suspect domestic abuse if unexplained injuries are present or if the patient’s explanation seems implausible. Ask direct questions, talk with the patient privately, and provide enough space to answer questions. If a patient discloses abuse, be explicit that physical and sexual violence are never acceptable. Offer assurance and unconditional positive regard. Skill in establishing rapport and communication are critical to help a patient feel comfortable and safe. Accept the answers given, reaffirming your desire to understand and help when you can. Remember, abuse and violence are never easy to talk about.

• Complete documentation. A physician’s notation in the medical record should include an objective report of the abuse history as reported by the patient, detailed drawings of physical findings, laboratory and radiologic findings, and any photographs of abuse injuries. Document in the chart that the symptoms or injuries treated are abuse related and request a follow-up appointment.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

• Know your state’s legal requirements. Every state has legislation designed to protect victims of domestic violence because spouse and partner abuse has been defined as a criminal act. Physicians must be aware of the specific laws and support services for abused persons available in their practice community. Remember to obtain informed consent from an abused person before disclosing the abuse diagnosis to a third party or the police. Elder and child abuse carries mandated reporting in all 50 states, including the District of Columbia.

• Assess the safety of children in the home. Ask directly whether or not children are safe in the home. If the children have been mistreated or are at risk for abuse, refer them to an emergency shelter or child protection services.

• Assess psychologic needs. Determine whether an abused person is using drugs or alcohol or is suicidal. Each requires urgent and appropriate intervention.

• Pregnancy and reproductive coercion. IPV contributes to unintended pregnancies and delayed prenatal care; however, becoming pregnant may also increase the frequency and severity of IPV. Poor outcomes also associated with IPV during pregnancy include preterm birth, low birth weight, and perinatal death. Reproductive coercion is defined by coercion from male partners to make their female partners pregnant or discontinue a current pregnancy.8 It also includes birth control sabotage, which is when a partner interferes with contraception, such as discarding birth control methods (pills/patches/rings, etc.), refusing to use barrier methods, and denying partner access to medical care to obtain birth control.

• Knowledge of community service providers. In caring for an abused patient, the physician’s primary role is to provide that person with good medical care and safe, reliable information about support services. These community services include counseling, home visits, mentoring support, and other community services and providers who have been specifically trained to help survivors of domestic violence. Respect an abused person’s ability to make appropriate choices and decide if and when he or she will leave a violent partner.

• Work to make the office a safe place to discuss domestic abuse. Work with local service providers to obtain sensitive posters and educational materials. Provide patients with educational materials about family violence and community resources. Ensure that these materials are offered in ways that allow patients privacy to access them. Placing them in bathrooms as well as waiting rooms is important. Local agencies may help you with this educational outreach. There are excellent online resources such as “The Family Violence Prevention Fund” (www.endabuse.org) or “The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence” (www.ncadv.org). Toll-free numbers such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline, 1-800-799-SAFE (1-800-799-7233) are also valuable resources for victims. These can be useful tools for working with women and men who experience interpersonal violence in their intimate relationships.

Domestic violence is a common problem and a complex public health issue that must be recognized and treated with sensitivity. In addition to recognizing abuse-related injuries and symptoms, family physicians can provide patients with life-saving information on community resources available to address domestic violence.

REFERENCES

1. National Coalition against Domestic Violence. www.ncadv.org. Accessed March 12, 2014.

2. U.S. Preventative Service Task Force. Screening for Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse of Elderly and Vulnerable Adults, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf12/ipvelder/ipvelderfinalrs.htm. Accessed March 12, 2014.

3. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Intimate partner violence; fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/ipvfacts.htm. Accessed March 26, 2014.

4. AAFP. Violence (Position Paper) (1994) (2011). http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/violence.html. Accessed March 18, 2014.

5. Tacket A, Wathen CN, MacMillan H. Should health professionals screen all women for domestic violence? Plos Med 2004;1:1–4.

6. Cornholm PF, Fogarty CT, Ambuel B, et al. Intimate partner violence. Am Fam Physician 2011;83(10):1165–1172.

7. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Intimate partner violence. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/. Accessed March 26, 2014.

8. Modi MN, Palmer S, Armstrong A. The role of Violence Against Women Act in addressing intimate partner violence: a public health issue. J Womens Health 2014;23(3):253–259.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Child maltreatment is an issue that ought to be in the forefront of a family physician’s mind any time they are evaluating and treating a child. Moreover, family physicians have a uniquely advantageous position for identifying possible abuse, given their relationship to the entire family unit as well as the pediatric patient.

It is important to remember that child abuse has not only immediate, but also long-term health consequences for the victims. As adults, they are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease, liver disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. Childhood trauma is a risk factor for borderline personality disorder, depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders. Victims are more likely to engage in sexual risk-taking as they reach adolescence, and they are nine times as likely to become involved in criminal activities. There is an increased likelihood that victims will smoke cigarettes, abuse alcohol, or take illicit drugs during their lifetime, and they are more likely to themselves become perpetrators of interpersonal violence.1,2

Definition and Classification

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) of 2010 defines child abuse as “at a minimum, any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”3 This federal definition is a minimum, and definitions may vary from state to state.4 From a clinical perspective, child maltreatment can include neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse. Neglect, or the failure of a parent or caregiver to provide for a child’s basic needs, may be in the form of physical, medical, educational, or emotional neglect. Physical abuse, that is, nonaccidental trauma inflicted by a parent or caregiver, may include shaking, hitting, choking, burning, or any number of other acts of harm. Emotional abuse, also known as psychological abuse, can include withholding affection, excessive criticism, threats of harm, and other behaviors that can ultimately damage a child’s emotional development and well-being. Finally, sexual abuse is defined by CAPTA as “the employment, use, persuasion, inducement, enticement, or coercion of any child to engage in, or assist in any other person to engage in, any sexually explicit conduct for the purpose of producing a visual depiction of such conduct; or the rape, and in cases or caretaker or interfamilial relationships, statutory rape, molestation, prostitution, or other form of sexual exploitation of children, or incest with children.”3

Prevalence

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2012 there were 3.4 million referrals made to CPS agencies nationwide involving concerns of maltreatment of 6.3 million children. Of these, 2.1 million reports were investigated, and as a result one-fifth of these found at least one child victim of abuse or neglect—a total of 686,000 children. The vast majority of these cases were neglect (>75%), followed by physical abuse (>15%), sexual abuse (<10%), and finally psychological maltreatment (<10%).1 Per the National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4), which looked at the years 2005 to 2006, one child in every 25 is a victim of abuse each year.

Fatalities occurred at a rate of 2.2 deaths per 100,000 children. Of these, 70% were attributed to neglect or a combination of neglect and another form of abuse, and 44.3% were attributed to physical abuse or a combination of physical abuse and another form of abuse. 70% of those that died were under the age of 3.5

A significant amount of data amassed over the last several decades gives insight into victim, perpetrator, and family characteristics. Children are most vulnerable from birth to 1 year of age, and girls are abused at just slightly higher rates than boys. Caucasian children are at highest risk, followed by Hispanic and African American children.5 Children with disabilities have been found to have lower rates of physical abuse but significantly higher rates of emotional neglect, and those who are physically abused have higher rates of serious injury or harm.6

Greater than 80% of perpetrators are parents, followed by other relatives and unmarried partners of parents, and a greater number of perpetrators are women than men. The incidence of maltreatment is higher for children with no parent in the labor force and those with an unemployed parent and lowest for those with employed parents. According to the NIS-4, children in low socioeconomic households experienced abuse at a rate five times higher than other children—they are three times more likely to be abused and seven times more likely to be neglected. Children whose single-parent had a live-in partner had more than 10 times the rate of abuse and 8 times the rate of neglect compared with children living with married biological parents.7

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

Abuse or neglect may come to the attention of a clinician through any number of presentations. Physical injuries are often not detected or reported, particularly if they are minor and do not require medical attention, and sexual abuse rarely results in abnormal physical examination findings. Rather, children are reported as suspected victims of abuse when an individual reports a suspicious injury or witnesses an abusive event, a caregiver notices symptoms and brings the child for medical attention without recognizing that the child has been injured, the abuser is concerned that the injury is severe enough to warrant medical care, or the child discloses the abuse.8,9

History

As with any medical problem, a thorough and detailed medical history is of vital importance in the evaluation of suspected child abuse. In addition to a standard general medical, developmental, and social history, caregivers should also be asked about pregnancy history, child behavior (do they consider the child to be difficult?), home life stressors, substance abuse by people living in the home with the child, and the overall discipline philosophy of the caregiver(s). It is important to maintain a non-judgmental tone throughout the interview, and use open-ended questions whenever possible. If the child is able to give a history, they should be questioned separately from the caregiver. Statements made by the caregiver and the child concerning the mechanism of injury and the accompanying circumstances should be documented verbatim. The following should raise suspicion for nonaccidental trauma: vague or incomplete explanations for significant injuries, changing explanations, explanations that are inconsistent with a child’s developmental stage or with the severity of injury, or inconsistent explanations from one witness to another.8

If sexual abuse is suspected, it is essential to interview the caregiver and the child separately in order to avoid any biasing of the child. Explain that this interview is for medical purposes and that a more detailed, forensic interview may be required at a later time. To establish rapport, the clinician should start by talking to the child about nonthreatening topics, letting the child know that it is okay to talk to doctors about embarrassing or uncomfortable things. Leading questions should be avoided, and developmentally appropriate language should be used. Again, any descriptions of abuse should be recorded verbatim.9

Physicians must be aware of their local resources, and if a child advocacy center or specialized clinic is available and acuity allows, it is often most appropriate to refer the child for comprehensive interviewing, examination, and treatment in order to minimize the number of interviews required.9

Physical Examination

Minor accidental trauma is a common occurrence in childhood, and it is important to consider the stated mechanism of injury in addition to the injury pattern before concluding that abuse has occurred. While injuries in various stages of healing; injuries to multiple body parts; bruising on the torso, ear, or neck in a child younger than 4; or bruising of any body part in a child younger than 4 months are all concerning for abuse, no pattern of injury indicates abuse with absolute certainty. A thorough physical examination is crucial, particularly because the history is often incomplete or falsified.10

Children should be observed for level of consciousness, responsiveness, and overall demeanor, and their height, weight, and head circumference should be obtained. Findings concerning for neglect may be noted during the general assessment, including failure to thrive, dental caries, patchy hair loss (secondary to malnutrition), and severe diaper dermatitis. Information gained via nonverbal cues may be helpful in safety planning, particularly if the child displays fear of the abuser.8

All injuries should be carefully described and documented as well as photographed. Some bruising may take some days to appear, so reexamination in 1 to 2 days can be useful. Bruising from accidental trauma tends to occur overlying bony prominences where bruising secondary to abuse tends to involve the buttocks, trunk, neck, and head. Additionally bruising from nonaccidental trauma may have a pattern consistent with an object used to inflict injury, that is, linear bruising inflicted by a belt or cord, hand-shaped bruises. Inflicted burns are typically well demarcated, and splash marks are notably absent.8

The neck, torso, and extremities should be palpated to detect occult fracture, and a neurologic examination should be performed to check for spinal cord injury. If possible, a fundoscopic examination should be performed looking for retinal hemorrhages. Finally, the mouth and teeth should be evaluated looking for caries or inflicted injury.10

When sexual abuse is suspected, if there is not an injury that demands emergent examination, physicians should consider referring the child to a center specializing in abuse. Forensic evidence can be collected if the abuse has occurred within the past 72 hours, and some states recommend collecting evidence even up to 96 hours after the abuse. The examination should be explained to the child, and a chaperone should be present for support. Instrumentation is rarely required—female genitalia can typically be examined with labial traction and separation. If instrumentation is required, consider sedating the child for comfort. Finally, it is important to explain to the parents and the child (if appropriate) that sexual abuse rarely results in examination abnormalities and that a normal examination does not rule in or rule out the possibility of abuse.9

Laboratory Studies

The type and severity of injury will dictate appropriate laboratory tests for each case. A coagulopathy workup may be indicated if abuse is suspected on the basis of significant bruising. Liver enzymes and an electrolyte panel may be indicated to look for occult renal and abdominal injuries. Additionally, a complete metabolic panel, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, and a parathyroid hormone levels can be obtained to evaluate for malnutrition and bone mineralization disorders.10

Because the transmission of STIs is uncommon in sexual abuse cases, universal screening is not recommended. Rather, consider screening for STIs under the following circumstances: child has experienced penetration of the genitalia or anus, the abuser is a stranger, the abuser is known to be infected or suspected to be infected with STIs, the child has another household contact with an STI, the child lives in a community with high rates of STIs, and of course, if the child has signs or symptoms of an STI.9

Imaging

When abuse is suspected and a child has a known fracture or is under the age of 2, a complete skeletal survey is recommended. A so-called “babygram” is not adequate to fully evaluate for skeletal injuries in an infant. If intracranial injury is suspected, an MRI of the head and neck is recommended. This may be more sensitive than CT in finding subtle intracranial injury patterns and is more sensitive than CT and plain films in detecting cervical spine injuries.8

Certain radiographic findings are more concerning for abuse than others. Rib fractures; sternal, scapular, and spinous process fractures; and metaphyseal fractures are considered highly specific for nonaccidental trauma. Multiple fractures and fractures in different stages of healing also raise concerns for child abuse.10

Differential Diagnosis

As discussed previously, no injury pattern or radiographic finding is absolutely pathognomonic for child abuse. It may be important to rule out coagulopathies, osteogenesis imperfecta, and other genetic disorders whose signs may mimic those of abuse. Certainly accidental trauma must be ruled out, although it is important to keep in mind that accidental and nonaccidental trauma can coincide.

TREATMENT

Treatment of immediate injuries is the physician’s top priority, and ensuring the child’s continuing safety follows closely behind. It may be appropriate to admit the child to the hospital throughout the evaluation and treatment process to provide that safety.11 Beyond immediate concerns, the treatment of child abuse requires a multidisciplinary approach and should involve the entire family. Physicians should be aware of local resources available for not only the abused child but also the abusive caregiver and the rest of the family.12

Reporting

Physicians are mandated by law to report any suspected child abuse to local child protective services or law enforcement. Child protective services will then determine whether the case warrants an investigation and proceed accordingly. The Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 800-4-A-CHILD (800-422-4453) is an excellent resource and can assist physicians in contacting the appropriate agencies.10

Referrals

Once again, the evaluation and treatment of child maltreatment is a complex endeavor and requires a multidisciplinary approach. If the local area has a child advocacy center or other practice that specializes in child abuse, it is in the best interest of the child to engage with this center early in the process, so that they can benefit from the medical and psychological resources that are available.

REFERENCES

1. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2013. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/long_term_consequences.cfm. Accessed July 17, 2014.

2. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–258.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Administration on children, Youth and Families Children’s Bureau. The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2010. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/capta. Accessed July 17, 2014.

4. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect in Federal Law. https://www.childwelfare.gov/can/defining/federal.cfm. Accessed July 17, 2014.

5. Child Welfare Information Gateway. What is child abuse and neglect? Recognizing the signs and symptoms. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2013. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/whatiscan.cfm. Accessed July 17, 2014.

6. Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, executive summary. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; 2010 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2014.

7. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Child maltreatment 2012: summary of key findings. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2014. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/canstats.cfm. Accessed July 17, 2014.

8. Kellogg ND; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics 2007;119:1232.

9. Jenny C, Crawford-Jakubiak JE, Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. The evaluation of children in the primary care setting when sexual abuse is suspected. Pediatrics 2013;132:e558.

10. Kodner C, Wetherton A. Diagnosis and management of physical abuse in children. Am Fam Physician 2013;88:669–675.

11. American Academy of Family Physicians Policy. Child Abuse. 2013. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/child-abuse.html. Accessed July 17, 2014.

12. American Academy of Family Physicians Policy. Medical Necessity for the Hospitalization of the Abused and Neglected Child. 2013. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/medical-necessity.html. Accessed July 17, 2014.

| Evaluation and Management Sexual Assault Victim |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, sexual assault is a crime of violence against a person’s body and will. Sex offenders use physical and/or psychological aggression or coercion to victimize, in the process often threatening a victim’s sense of privacy, safety, autonomy, and well-being. Sexual assault is the most underreported violent crime secondary to multiple pressures on the victim.1

Many misconceptions are perpetuated about sexual assault. The most common is the assumption that rape is motivated by sexual desire. Rape is a violent crime, motivated by anger or the need for power and control.2 Another is that sexual assault is limited to a specific gender; rather, no gender or sexual preference is immune from assault.3

Epidemiology

National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence 2010 Survey underscored the pervasiveness of this violence, the immediate impacts of victimization, and the lifelong health consequences related to sexual violence. There was a significantly disproportionate impact on women compared with men. Nearly 1 in 5 women (17%) and 1 in 71 men (1%) have been raped in their lifetime. Most female victims of completed rape (80%) experienced their first rape before the age of 25 and almost half (42%) experienced their first rape before the age of 18 (30% between 11 and 17 years old and 12% at or before the age of 10). More than a quarter of male victims of completed rape (28%) were first raped when they were 10 years old or younger.

The survey was also one of the first to attempt to survey sexual preference minorities in order to evaluate the impact on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community as well. The survey found lifetime prevalence of rape in women to be approximately 1 in 8 lesbian women (13%), nearly 1 in 2 of bisexual women (46%), and 1 in 6 heterosexual women (17%). In contrast, while underpowered to report completed rape except for heterosexual men (0.7%), gay and bisexual men had similar rates of sexual violence compared with women. Four in 10 gay men (40%), nearly 1 in 2 bisexual men (47%), and 1 in 5 heterosexual men (21%) have experienced sexual violence other than rape in their lifetime,3 and approximately 50% of rape victims have some acquaintance with their attackers.4

A 2012 Swedish study in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence reported extragenital injuries were almost three times as common as genital injuries, 58% (263/465) compared with 20% (90/450).5 Genital injuries are not an inevitable consequence of rape, and lack of genital injuries does not imply consensual intercourse.4 Only 1% to 2% of sexual assault victims require hospitalization.2,4

Evidence beyond 48 to 72 hours after an assault often is difficult to recover or may be invalid; however, with advances in technology, evidence should be collected and submitted regardless if it is beyond the cutoff point. It is imperative to document the time frame (from time of assault to medical examination) and to encourage victims to proceed with evidence collection as soon as possible, regardless if the victim plans to report the sexual assault at the time of presentation. Multidisciplinary sexual assault teams are encouraged by the U.S. Department of Justice and the American College of Emergency Physicians and may be available in some medical centers.

Consent6

Informed consent or refusal in a language the patient understands should be obtained for each of the following components of the sexual assault evaluation. Follow facility policy for seeking patients’ consent for medical evaluation and treatment. Informed consent of patients for medical evaluation and treatment typically is needed for the following:

General medical care | Evidence collection |

• Notification to law enforcement or other authority | • Pregnancy testing and care |

• Evidence collection and release | • Testing and prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infection (STIs) |

• Toxicology screening | • HIV prophylaxis |

• Release of information and evidence to criminal justice system personnel, SART/SARRT members, and partnering service providers | • Photographs, including colposcopic images |

• Contact with patients for reasons related to their criminal sexual assault case | • Permission to contact the patient for medical purposes |

• Patient notification in case of a DNA match or additional victims | • Release of medical information |

• Transferal of evidence to law enforcement personnel |

|

The history should focus on explicit details of the sexual assault for forensic purposes. Avoid legal terms such as “rape” or “abuse.” Provide a quiet, secure, and private environment. Allow 30 to 60 minutes for the history and the physical examination. Victims should be offered a chaperone for any interaction.

The following details of the history should be obtained:

• Was there drug or alcohol use by the patient before, during, or after the assault?

• Where and when did the assault take place?

• Was there touching or penetration of any part of the patient’s body with a penis, finger, or any object?

• Was a condom used?

• Was there use of any kind of spermicidal foam or gel?

• Is the patient using any other form of birth control (intrauterine device, oral, etc.)?

• Is the patient undergoing fertility treatment?

• Was the patient kissed, licked, or bitten by the assailant? If so where?

• Did the patient clean up in any way after the assault?

• Specifically, did the patient:

• Void

• Insert or remove a tampon

• Change a sanitary pad

• Shower, bathe, douche, wipe

• Change clothes

• Brush their teeth, gargle, chew gum, smoke, eat, drink OR

• Take medications before coming to the emergency department (ED)? If so, when?

• Where are the original clothes, sanitary pads, or cleaning accessories?

• Who brought the patient to the ED?

• What are the names and agencies of the emergency medical services (EMS) providers OR the name and contact information of any stranger, friend, or family member who accompanied the patient?

Physical Examination

Most hospitals have a standard rape kit with instructions to help guide the clinician through the collection and preservation of evidence for forensic evaluation.3 Once the kit is opened, the “chain of evidence” must be maintained; evidence cannot be left unattended.4,8

The examiner should prevent cross-contamination of evidence by changing gloves whenever cross-contamination could occur. Clearly document all findings.

• Before the patient undresses, place a clean hospital sheet on the floor to be a barrier for the collection paper.

• Allow the patient to remove and place each piece of clothing being collected in a separate paper bag. Handle all clothing with gloved hands to prevent contamination of evidence, and it should be handled primarily by the patient.7 A female chaperone should be present for a male physician.

• Clothing can be collected up to 1 month after the assault, provided the items have not been laundered. Clothing should be placed in paper bags.8

• Photograph and recover any trace evidence, including sand, soil, leaves, grass, and biological secretions. Note the body location of the collection.

• Note all injuries by documenting the location, size, and complete description of any trauma, including bite marks, strangulation injuries, or areas of point tenderness, especially those occurring around the mouth, breasts, thighs, wrists, upper arms, legs, back, and anogenital region. A body map may be useful to aid in documentation. Genital trauma occurs more commonly in postmenopausal women.7,9

• Identify and recover moist secretions with a dry swab. Dry secretions should be moistened with a damp swab and then recovered with a dry swab. Debris should be scraped onto a bindle.

• Use a Wood’s lamp to examine the patient’s thighs for fluorescing semen and urine stains. Swab any highlighted areas.

• On the basis of the history obtained, follow the instructions for the pertinent portions of the sexual assault evidence collection kit.

• Toluidine blue dye may be used to identify minor external genital and anal injuries, but it may cause discomfort (burning). Lacerations expose the deeper dermis containing nuclei that absorb this stain.

• A wet mount should be done to check for the presence of bacterial vaginosis, trichomonads, yeast, and sperm. Motile sperm may be seen up to 8 hours postcoitus and nonmotile sperm can be detected beyond 72 hours. Vaginal swabbing should also be collected during pelvic examination for Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

• The absence of sperm may indicate that the assailant had undergone a vasectomy.

• If blood is present at the rectum, anoscopy or sigmoidoscopy and rectal digital examination should be performed on the basis of patient’s history.4,10

• The patient should pluck approximately 15 to 20 pubic hairs to serve as samples for reference.10

• Obtain rectal aspiration in case of anal assault by injecting sterile saline into the rectum and then aspirating.

• Swabs from the victim’s penis should be collected and may be examined for saliva if there is a history of oral copulation.4

In cases where the laboratories are going to be processed by a crime laboratory, following the appropriate local procedure at initial presentation is critical for proper evidence collection. This may require duplicate laboratory collection if laboratories are required to treat the patient. Consider tests that may be appropriate for a given patient:

• Serum or urine pregnancy test

• Rule out an established pregnancy; 1% to 5% of sexual assaults result in pregnancy.

• Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and syphilis testing

• In cases where prophylaxis will be given and chronic abuse is not suspected, cultures and syphilis testing are not necessary.

• Test at initial presentation and repeat at 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months.

• Hepatitis B surface antibody

• Check for the immune status in the previously immunized patient. Hepatitis B testing is not indicated in the nonimmunized patient.

• HIV risk assessment and screening: Patients should be assessed for risk of HIV transmission following assault. (See HIV prophylaxis for additional information.)

• Initial visit and repeated at 3, 6, and 12 months from the date of exposure.

• There is a risk of less than 1% of infection after a one-time sexual encounter.

• Drugs of abuse and alcohol level in serum, urine, and toxicology.

• Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), flunitrazepam (“date rape drug”) serum, and/or urine level are often screened in the Rape Kits but may be performed at the primary hospital as well if medically indicated.

• Laboratory and radiographic studies as indicated.

• Additional testing may be performed with the Rape Kit and a contracted forensic lab.

TREATMENT

Medications

• Pregnancy prophylaxis: Regardless of a victim’s menstrual cycle, postcoital emergency contraception should be offered. In the United States, some of the available regimens for emergency contraception include levonorgestrel (Plan B) alone, the Yuzpe regimen (combination of oral contraceptive pills given in two doses 12 hours apart), and the progestin antagonist/agonist, ulipristal. Levonorgestrel is highly effective up to 72 hours postcoitus, and moderately effective up to 120 hours. Ulipristal, where available, is effective up to 120 hours after intercourse and is the preferred drug beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.12

• Sexually transmitted disease (STD) prophylaxis:12,13 The CDC recommends empiric therapy for common STIs. The recommendations are given below.

Empiric Therapy, per Centers for Disease Control 2010 Guidelines

Gonorrhea | Ceftriaxone 125 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO |

Chlamydial infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO (single dose) or Doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 7 d |

Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO (single dose) |

Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B vaccine without HBIG at the time of visit, then repeated at 1–2 and 4–6 moa |

aThe CDC recommends Hepatitis B vaccine as adequate protection. If there is known exposure to Hepatitis B, provider may consider HBIG within 14 days of exposure.

• HIV prophylaxis. HIV prophylaxis is controversial because of presumed low risk of transmission and the efficacy of antiretroviral drugs after sexual assault is extrapolated from a study of healthcare workers who had percutaneous exposures to HIV-infected blood.12–14

• Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be based on risk factors of HIV exposure (penetration, ejaculation occurred on mucous membranes, multiple assailants, mucosal lesions present on the assailant or survivor, or any other suspicious characteristics).

• PEP consists of zidovudine, and it should be prescribed with the consultation of an Infectious Disease Provider. The CDC recommends that patients be given an initial prescription for PEP for only 3 to 7 days with short-term follow-up for further counseling, medication, and HIV antibody monitoring.1,6,13

Referral

Provide patients with oral and written medical discharge instructions. Include a summary of the examination (e.g., evidence collected, tests conducted, medication prescribed or provided, information provided, and treatment received), medication doses to be taken, follow-up appointments needed or scheduled, and referrals. The discharge form could also include contact information and hours of operation for local advocacy programs.15,16

Follow-Up

An optimal time for a first medical follow-up contact is 24 to 48 hours following discharge. A medical visit should occur within 2 weeks of the acute evaluation; ongoing psychological and counseling support should be provided. A male victim should be referred to an urologist or proctologist. A child should be referred to a pediatrician.15,16

Follow-up appointment should include:14,16

• Pregnancy testing

• STD testing for patients who develop interim symptoms or who declined initial evaluation

• HIV testing

• Continuing Hepatitis B vaccine

Complications

Many victims can experience rape trauma syndrome. In the first phase, days to weeks, symptoms may include anger, fear, anxiety, physical pain, sleep disturbance, anorexia, shame, guilt, and intrusive thoughts. The second phase, “reorganization,” which may last for months, includes physical and emotional symptoms. Patients may experience musculoskeletal, genital, pelvic and or abdominal pain, anorexia, and insomnia. Dreams and nightmares are common and phobias may develop. Patients may develop chronic pain (pelvis, back), fibromyalgia, headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, poor overall health status, sexual dysfunction, somatoform disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, anxiety, depression, eating disorders, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder.14 Children who are sexually assaulted or abused may display variable nonspecific symptoms and/or physical findings.17

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence against Women; Kristin L. A national protocol for sexual assault medical forensic examinations: adults/adolescents. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women; 2013.

2. Geist RF. Sexually related trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1988;6:439.

3. Basile KC, Black MC, Breiding MJ, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention; 2011.

4. Fled Haus KM. Female and male sexual assault. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, eds. Emergency medicine—a comprehensive study guide. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:1952–1955.

5. Moller AS, Backstrom T, Sondergaard HP, et al. Patterns of injury and reported violence depending on relationship to assailant in female Swedish sexual assault victims. J Interpers Violence 2012;27(16):3131–3148.

6. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. Atlanta GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010.

7. Asher S, Award SH, Blackburn C, et al. Evaluation and management of the sexually assaulted or sexually abused patient. 2nd ed. Dallas, TX: American College of Emergency Physicians; 2013.

8. Hochbaum SR. The evaluation and treatment of the sexually assaulted patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1987;5:601.

9. Ramim SM, Stain AJ, Stone IC, et al. Sexual assault in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol 1992;80:860.

10. Dupre AR, Hampton HL, Morrison H, et al. Sexual assault. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1993;48:640–648.

11. The California medical protocol for examination of sexual assault and child sexual abuse victims; 2001:98. www.calema.ca.gov

12. Bates CK. Evaluation and Management of Adult Sexual Assault Victims. In: Moreira ME, ed. Uptodate. UpToDate.com. Published November 5, 2012. Accessed March 18, 2014.

13. Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1–110.

14. Luce H, Schrager S. Sexual assault of women. Am Fam Physicians 2010;81(4):489–495.

15. Burgess AW, Holmstrom LL. Rape: crisis and recovery. Bowie, MD: Robert J. Brady; 1979.

16. Support services: the Rape Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN at 1-800-656-HOPE). https://www.rainn.org/get-help/national-sexual-assault-hotline. Accessed June 2014.

17. Berkowitz CD. Abuse and neglect of children. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, et al., eds. Emergency medicine—a comprehensive study guide. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:115–117.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Acute musculoskeletal injuries are insults to bone, muscle, ligament, or tendon, resulting in a disruption of the normal anatomy. There is no consensus as to when an acute injury is considered chronic. The “acute phase” varies from 6 weeks to 6 months.

Epidemiology

• Ankle sprains account for 2 million injuries per year and 20% of all sports injuries.1

• Knee injuries account for around 1 million emergency department (ER) visits a year.2

• Low back pain has an estimated prevalence of 20% in the U.S. population and acute low back pain is the fifth most common complaint in a primary care setting.3

Etiology

Underlying conditions such as deconditioning, poor biomechanics, or osteoporosis can decrease tolerance of outside stressors and often contribute to acute symptoms, with or without trauma.

General Treatment Approach

Initial treatment involves stabilizing surrounding tissue to protect the injury, decreasing inflammation, and pain control. More specifically this includes:

• Imaging. Choice varies, but can include x-ray, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

• Reductions for joint dislocations.

• Splints or casts for fractures, ligament, and some tendon tears.

• Immobilization for sprains, strains, and fractures.

• Rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) to reduce inflammation.

• Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used but are controversial. A short course (5 to 7 days) can be beneficial for reducing inflammation and controlling pain, but in the long run may slow inflammatory-mediated healing.

• Opioids for pain control in fractures and dislocations.

• Muscle relaxants for pain control; this is most commonly used for acute back pain.

After initial treatment allows for healing and regeneration of affected tissue, most patients do well with physical therapy for strengthening and rehabilitation of the injured area. Some injuries require surgery for definitive treatment.

FRACTURES

Diagnosis

History

History should be obtained with attention to mechanism of injury and risk factors that render the patient susceptible for fracture or impaired healing. The type, direction, and speed of the force applied to the bone can help predict the injury before imaging is obtained. Fractures result from compressive, tensile, and/or sheer stress that overcomes the intrinsic strength of the normal bone. This may happen acutely or over time with repetitive loading, resultant microdamage of cortical bone, and subsequent failure of bone integrity. Acutely, the speed at which this force is loaded will determine the extent of the fracture. Rapid loading diminishes the bone’s ability to absorb force causing fragmentation, whereas slow loading causes a single fragment.

Physical Examination

For a suspected fracture, inspect the affected area for swelling, ecchymosis, asymmetry, and gross deformity; palpate for tenderness; and assess strength, range of motion (ROM), and neurovascular compromise. Key findings that favor fracture include point tenderness over bone, loss of function, and apprehension with movement. Examine the joints distal and proximal to the suspected fracture to evaluate for associated injuries.

Imaging

X-rays are the diagnostic imaging of choice. Multiple views should be obtained as a fracture must be visualized in two or more views to make the diagnosis. Fractures should be described in terms of location, open or closed, direction of fracture line, fragments, displacement, and angulation. If the radiograph does not reveal evidence of a fracture, CT or MRI may be indicated. Imaging of the joint above and below the fracture should be considered.

Treatment

Understanding the three stages of bone healing provides insight into the treatment process. The inflammatory stage begins within the first few hours of injury with hematoma formation and recruitment of inflammatory cells. Soft callus is laid around week 2 at the transition into the repair stage. By week 6, a hard callus replaces the soft, marking clinical union. During the final stage, remodeling, immature bone is replaced with mature bone and strength is regained by 3 to 6 months.

Bone healing is inhibited by smoking, malnutrition, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, and use of steroid, cytotoxic, or NSAID medications.4 Furthermore, other comorbidities such as bone density, nutrition, endocrine abnormalities, and the female athlete triad should be considered for patients having recurrent stress or low-impact fractures.

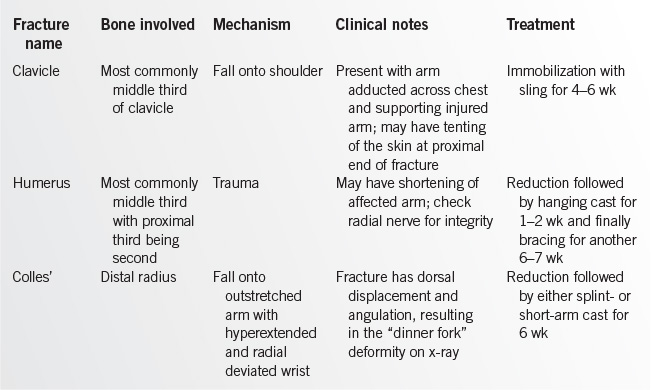

Immobilization via splinting or casting throughout the inflammatory and repair stages of bone healing is crucial. Any fracture that has significant displacement should be reduced prior to immobilization. Reduction can often be achieved in the office or emergency department, but more complicated fractures may require general anesthesia and/or surgery for definitive care. Always perform postreduction imaging and neurovascular examination. Surgery is indicated if misalignment or neurovascular complications are present or if reduction cannot be maintained. If clinical suspicion for fracture is high but radiographs are negative, immobilize as if a fracture is visualized. Specific management of common fractures is reviewed in Table 20.7-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree