Infections of the Hand

Patrick G. Marinello

Steven D. Maschke

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Encountering infections of the hand is relatively common for most hand surgeons, and these range from relatively benign to devastating. Prompt diagnosis and treatment should be the priority for all infections of the hand. Primary care and/or emergency medicine physicians oftentimes initially see these patients and are challenged with not only making the correct initial diagnosis but also knowing when to refer to a higher level of specialty care. How effective this channel of communication determines the timing and appropriateness of both diagnosis and treatment, which can greatly alter clinical outcomes. The hand surgeon is charged with determining the appropriateness of continued nonoperative care versus the need for operative intervention. The history, physical examination, and knowledge of hand anatomy with its many potential spaces, in conjunction with advanced imaging studies when indicated, guide the surgeon in making the correct diagnosis and determine appropriate management.

FLEXOR TENOSYNOVITIS

Indications/Contraindications

The volar surface of the hand and fingers frequently comes in contact with potentially harmful objects and environments. The flexor tendons and surrounding sheath are in within millimeters of the skin, making them susceptible to penetration from even minor trauma. Unlike a localized infection in the subcutaneous tissue, inoculation of the flexor tendon sheath provides the bacteria with a path of low resistance to migrate proximally and distally. An innocent-looking puncture wound has the ability to deliver a potentially devastating bacterial organism throughout the tendon sheath of a digit with potential proximal spread into the palm. Although most infections are a result of direct seeding with penetrating trauma, immunocompromised hosts such as patients with poorly controlled diabetes, malnutrition, and HIV are susceptible to hematogenous infections. Healthy patients presenting with flexor tenosynovitis (FTS) without antecedent trauma should have gonococcal infection in the differential diagnosis.

In 1943, Kanavel described four cardinal signs of FTS: (a) flexed posture of the finger, (b) fusiform swelling of the finger, (c) tenderness over the entire course of the flexor tendon sheath, and (d) pain on passive extension of the finger (added later). The bacterial infection causes local edema of the tendon, sheath, and surrounding soft tissues. The vincular and intratendinous vascular supply and nutritional support of the tendon become compromised from the elevated pressure within the sheath with the end result being potential tendon necrosis and rupture. Additionally, the gliding mechanism is quickly compromised leading to stiffness and scarring within the tendon sheath.

Patients either will present with a known injury with progressive pain and swelling or may not recall an antecedent event prior to the onset of symptoms. A high index of suspicion for FTS is paramount and should prompt urgent consultation and evaluation by a hand specialist. If

early in the disease process, a trial of antibiotics, immobilization, and elevation can be tried for a period of 12 to 24 hours. This should be administered in a hospital observation unit where the patient can be closely monitored. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist can be helpful in selecting appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy targeted at the most common pathogens and taking hospital-specific antibiotic resistance into account. If no improvement is seen during this short time frame, the patient is urgently brought to the operating room for a proper irrigation and debridement.

early in the disease process, a trial of antibiotics, immobilization, and elevation can be tried for a period of 12 to 24 hours. This should be administered in a hospital observation unit where the patient can be closely monitored. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist can be helpful in selecting appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy targeted at the most common pathogens and taking hospital-specific antibiotic resistance into account. If no improvement is seen during this short time frame, the patient is urgently brought to the operating room for a proper irrigation and debridement.

The long-term sequela of inadequate or delayed treatment of FTS can be devastating, and this condition must be treated aggressively. Functional loss of the affected digits due to stiffness from adhesions, possible tendon necrosis/rupture, as well as spread of the infection more proximally to potential spaces of the hand are all potential consequences of poor management. Severe cases of FTS may lead to digital amputation. All hand surgeons must have a low threshold to perform an expeditious and complete irrigation and debridement in the operating room. Generally, the risk of inaction is much higher for the patient than are the potential complications from surgical intervention.

Pre-Op Planning and Anatomy

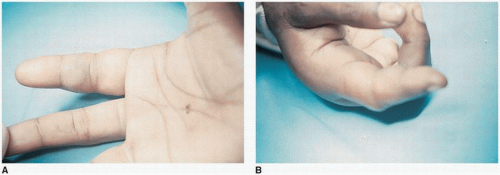

The clinical history of a penetrating injury or spontaneous swelling in the digit of an immunocompromised patient along with positive Kanavel’s signs should be sufficient to make the diagnosis of FTS. All digits need to be examined carefully as more than one finger may be involved. Also, careful evaluation of the palm and wrist for deep space infection or communication between the fingers is critical (Fig. 4-1).

Knowledge of the anatomy of the flexor tendon sheath aids in understanding where the infection may spread. In the middle three digits (index, long, and ring finger), the tendon sheaths run from the A1 pulley to the FDP insertion. For the thumb and the little finger, the tendon sheaths extend more proximally to the radial and ulnar bursas, respectively. If the infection penetrates the tendon sheath of the thumb or small finger, it has the potential to spread into the thenar or hypothenar spaces. Communication at the level of the wrist occurs in a potential space between the flexor digitorum profundus tendons and the fascia of the pronator quadratus muscle. Infection in this space, known as Parona’s space, leads to a “horseshoe” abscess. Tenderness and swelling in Parona’s space should always be evaluated, and when present, surgical decompression proximal to the wrist flexion crease is indicated.

Standard orthogonal view x-ray examination of the affected hand is recommended for evaluation of bony involvement or associated foreign bodies. Advanced imaging with an MRI or ultrasound is not indicated when the clinical diagnosis is clear but can be helpful when the diagnosis remains elusive. Laboratory evaluation is helpful. Complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are useful adjuncts to help confirm a diagnosis. However, it is not uncommon for the acute phase reactants to be normal in the early

stages of FTS. Trending laboratory values postoperatively can be useful to determine resolution of infection.

stages of FTS. Trending laboratory values postoperatively can be useful to determine resolution of infection.

Antibiotics are a critical part of the treatment for this condition. Unfortunately, in our personal experience, most patients have received antibiotics prior to our consultation, and this may affect our ability to isolate the offending organism and target our antibiotic regimen. If the patient is stable, it is our practice to hold antibiotic therapy until after cultures have been obtained either via aspiration of the tendon sheath or intraoperatively.

Surgical Technique

The patient is placed supine on the operating table with the affected upper extremity on a hand table. A well-padded proximal pneumatic tourniquet is applied on the upper arm. For cases of infection, general anesthesia is typically used at our institution. In the acidic environment of an ongoing infection, local infiltrative anesthetic is not as effective. Surgical loupes magnification and appropriate operating room lighting are beneficial.

The upper extremity is then prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. A preoperative surgical time-out is performed verifying the correct patient, laterality, anatomic location of the surgery, allergies, preoperative antibiotics (or if they are held), and the presence of necessary equipment and personal. The arm is gravity exsanguinated, and the tourniquet is inflated to 250 mm Hg. No Esmarch bandage is used for exsanguination in cases of infection to diminish risk of spread. We typically hold preoperative antibiotics, and the patient receives them after cultures are obtained.

A midaxial incision is made centered on the PIP joint of the affected digit (Fig. 4-2). We incorporate the traumatic wound when appropriate but will not alter our incision to include wounds away from the standard approach. The incision is made on the side of the digit with the least contact. For the index, long, and ring fingers, the incision is typically made on the ulnar side while the incision is made on the radial side for the small finger and thumb. The midaxial incision is extended both proximally and distally as far as needed to allow safe and complete surgical decompression. The neurovascular bundle is identified, dissected, retracted with the palmar flap, and protected (Fig. 4-3). The flexor sheath is identified, and the A3 pulley is incised (Fig. 4-4). Specimens for Gram stain and microbiology can be collected at this time. Careful but deliberate debridement of hypertrophic synovium is completed at this time. If antibiotics were held, after collection of specimens for microbiology, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy can be initiated. In more severe infections or delayed treatment, larger incisions and multiple windows into the flexor sheath may be required to accomplish adequate debridement.

Attention is then turned to the palm. A short Brunner incision at the MP flexion crease of the affected digit is made, and blunt dissection down to the A1 pulley is completed (Fig. 4-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree