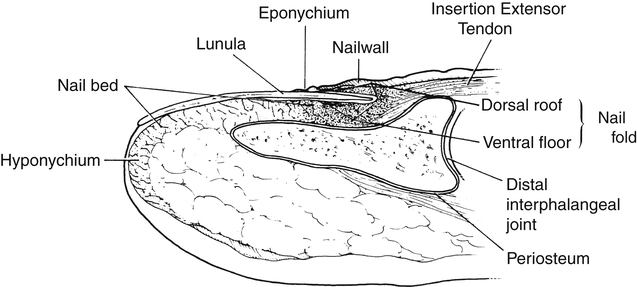

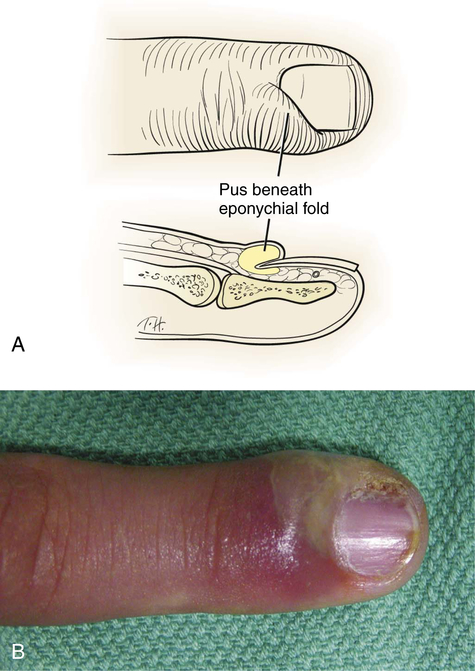

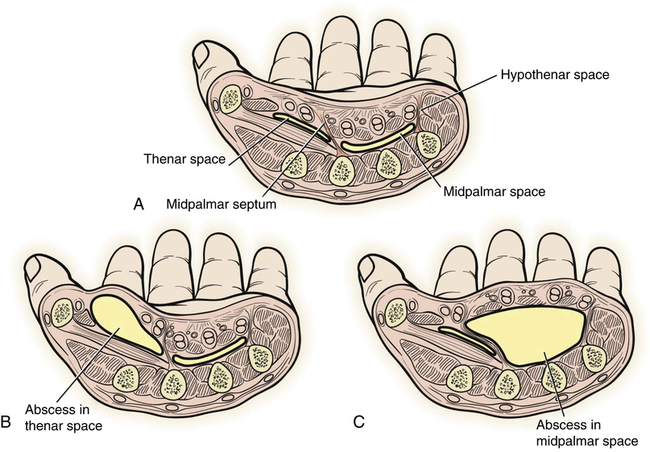

In a 2008 practice analysis by the Hand Therapy Certification Commission, in consultation with Professional Examination Service, most therapists who responded reported treating clients who had infection as part of their diagnosis. Fifty-six percent of respondents reported infections in 1% to 10% of their patients, and 26% reported infections in 11% to 25% of their patient population.1 The terms inflammation and infection differ in that inflammation is, “a localized protective reaction of tissue to irritation, injury, or infection, characterized by pain, redness, swelling, and sometimes loss of function.”2 Infection is the “invasion of the body by pathogenic microorganisms.”3 Infection can lead to loss of tissue and even death in some cases if left untreated. It can occur with a minor scratch or with a major trauma. Since the initial use of penicillin in 1942,4,5 the incidence of hand infections and complications have greatly decreased. However, bacteria evolves, and the sensitivity of bacteria to antibiotics can change. Many infected wounds contain more than one type of offending organism, and some bacteria have adapted to a point that available antibiotics may not affect them. One such resistant organism is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).4 There has been an increased incidence of MRSA in hospitals and the community. By 2003, more than 50% of Staphylococcus aureus isolates in US hospitals were MRSA.4 When the skin is broken, bacteria contaminates the wound. This bacteria will either be fought off by the host or develop into an infection. The susceptibility of the host to infection depends upon many factors, such as the severity of injury and whether multi-systems are involved. Certain conditions increase the susceptibility to infections, such as diabetes mellitus,6,7,8 AIDS, Raynaud’s disease,7 malnutrition, obesity,6,7 renal failure, burns, immunosuppression seen with cancer or transplantation recipients,6 alcoholism, drug abuse, and others.7 Many types of microorganisms can cause infection in the hand, but the most common is Staphylococcus aureus, which may comprise from 50% to 80% of all hand infections.7 The second most common pathogen found in hand infections is β-hemolytic Streptococcus. Many wounds contain more than one pathogen, such as in bite injuries.7,9,10 Infections may start out as cellulitis, a superficial infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that normally does not produce an abscess (a localized collection of pus). The involved area is tender, warm, and marked by erythema. Incision and drainage are not routinely performed for cellulitis, but the procedure is done if an abscess develops.7,10 A trivial injury left untreated may lead to a very serious hand infection that progresses rapidly, called lymphangitis. Lymphangitis can involve the superficial lymphatic vessels that arise from the skin, but can also lead to the deep lymphatic vessels following the course of the arterial system. Some signs of lymphangitis could include fever, nausea, tachycardia, or red streaking up the hand and forearm along the lymphatic pathways. An abscess may form at the elbow or axilla if the infection is left untreated. The most common cause of lymphangitis is a Streptococcus organism5 (Fig. 35-1). Cellulitis and lymphangitis are considered superficial spreading infections. There are other types of infections found in the hand, such as subcutaneous abscesses, synovial sheath, and fascial space infections. Subcutaneous abscesses include paronychias, felons, and subepidermal abscesses. With any infection of the hand, even if located on the palmar surface, more edema may be present dorsally on the hand because of the anatomy and direction of flow of the lymphatic system.7 The perionychium comprises the whole nail structure consisting of the nail bed (germinal and sterile matrix), nail plate, nail fold, eponychium, hyponychium, and paronychium (Fig. 35-2). The nail fold is the proximal depression into which the proximal nail fits. The nail fold has a dorsal roof (eponychium).11,12 The lunula is the white arc seen at the base of the nail just distal to the eponychium. The highly vacularized nail bed shows through the nail normally appearing pink in color.12 The hyponychium, between the nail bed and the distal nail, helps in protection against fungal and bacterial contamination. The hyponychium contains leukocytes and lymphocytes that provide defense against invasion of the subungual area (under the nail). The paronychium is the lateral skin on the edge of the nail plate and bed.11,12 The fingernail is not only important aesthetically but is also needed functionally. The nail provides counter-pressure against the finger when pinching or holding onto an object, which improves the sensitivity. The fingernail is important for protection, can help regulate temperature, and promotes dexterity.11,12 In a traumatic fingertip injury, a subungual hematoma (confined mass of blood under the nail) may develop from bleeding underneath the nail plate. Bleeding separates the nail bed from the nail plate and can cause throbbing pain due to pressure. The hematoma can be evacuated by forming a hole in the nail. This procedure is performed by the physician.11 Paronychia refers to an infection of the soft tissue around the nail or nail plate (Fig. 35-3). It is the most common infection in the hand.13 A hangnail, nail biting, or manicure are often the cause and can start on the lateral border of the nail.13,14 In children, paronychia is associated with thumb or finger sucking. Erythema, swelling, and pain may occur at the lateral fold or base of the fingernail.14 The most common causative organism of an acute paronychia is Staphylococcus aureus.9,10,15 Chronic paronychia is more common in people who immerse their hands in water or detergents frequently. Middle-aged women are most commonly affected, as are people who work in jobs that require frequent cleaning. Finger suckers and individuals with diabetes are more susceptible to chronic paronychias.13 Normally, the hyponychium protects the subungual space from invading organisms. When the finger is repeatedly immersed in water and exposed to alkaline, the protective barrier is violated and bacterial or fungal organisms more easily enter.11 The most common offender is Candida albacans and other fungal organisms.7,13 Individuals with chronic paronychias suffer with repeated erythema and drainage. A decrease in vascularity of the nail fold due to frequent infections may increase the chance of more invading organisms causing new episodes. If not adequately treated, the nail may exhibit permanent nail deformity (Fig. 35-4). When the infection involves the tissue overlying the base of the nail in addition to one lateral fold beside the nail, it is more accurately called an eponychia. In an eponychia, pus can develop near the lunula, the white arch visable at the base of some fingernails.13 An infection can begin on one side of the nail as a paronychia, then less commonly extend around the base to the opposite side of the nail, called a run-around infection.7,10 Therefore, an eponychia can develop from an extension of an untreated paronychia. An infection involving the distal finger pad is called a felon. The finger pad or pulp is divided into multiple compartments by fibrous septa that connect to skin and extend to bone. A subcutaneous abscess (pus) in these tiny compartments causes pressure with swelling and can create redness and an intense pain. A penetrating trauma, such as with splinters or finger-stick blood tests, can be the mechanism of injury.10,14 If left untreated, the abscess from the felon can extend into the distal phalanx and lead to osteomyelitis (inflammation of bone and marrow) or osteitis (inflammation of bone). The tip of the finger holds the highest concentration of sensory receptors in the hand,13 so when pressure develops in the finger pulp, pain is usually severe. The longer the felon is untreated, the greater is the chance that increased tension in the septal compartments causes shut off of blood supply to the distal phalanx.9 The flexor tendons in the hand move within synovial sheaths. Within these sheaths, there is poor vascularization, but the tendons receive much of their nutrition by diffusion from the synovial fluid.13 This synovial fluid environment is enticing for bacterial growth. When infection occurs within the enclosed sheath, a purulent flexor tenosynovitis (or pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis) develops.7,14 Increased pressure from bacterial proliferation within the sheath leads to even less blood supply (through the vincular system) and can cause tendon necrosis and rupture. Flexor sheath infections are most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus and β-hemolytic Streptococcus.13,14 Dr. Allen Kanavel, a pioneer in the treatment of hand infections in the early twentieth century, described four signs (Kanavel’s cardinal signs) to identify purulent flexor tenosynovitis. These are 1) a semi-flexed finger position, 2) uniform volar swelling of the finger, 3) tenderness along the tendon sheath, and 4) excruciating pain with passive extension of the finger.7,13,14 Even if treated early, purulent flexor tenosynovitis can lead to permanent tendon scarring and lack of function. Tendon necrosis or the spread of infection to deep fascial spaces can occur if the infection advances. Although more uncommon, radial and ulnar bursal infections may occur in association with flexor tendon sheath infections of the thumb or small fingers. There may be tenderness and swelling at the distal wrist crease, along the hypothenar or thenar eminence, in addition to the cardinal signs of Kanavel in either the small finger or thumb.13 Infection can develop or pus may accumulate in a number of potential spaces in the hand (Fig. 35-5). Potential spaces are the 1) thenar, 2) hypothenar, 3) midpalmar spaces in the hand, and 4) Parona’s space in the forearm. More superficial spaces are the 5) dorsal subcutaneous space, 6) dorsal subaponeurotic space, and the 7) interdigital web spaces (collar-button abscesses occur here).13 Infection may be caused by a penetrating injury or by spread from an adjacent flexor tendon sheath infection. These clients may present with tenderness and swelling over the palmar spaces. Dorsal hand swelling is also present, as in most other hand infections, since the palm consists of tight fascia that limits the accumulation of swelling. The dorsal hand anatomy consists of a more loosely organized connective tissue that allows greater expansion of edema in the soft tissue.13 The presence of infection in the fascial spaces is treated as a medical emergency and usually requires surgical drainage.7,13 Infection in the bone, or osteomyelitis, can result when an infection is not eradicated in nearby soft tissue or if there is a penetrating trauma.13,16 A felon or bite injury can lead to osteomyelitis, and Staphylococcus is the most common pathogen. Intact bone cortex provides a good barrier to penetration of pathogens, but trauma to the bone allows a pathway for infection. If local inflammation causes necrosis of the bone, called a sequestrum, pathogens can more easily live there due to the deficient vascularity. Antibiotics are less effective in areas of necrotic bone.16 When hardware (such as, pins, screws, and plates) are required for fixation of a bone fracture, pathogens can enter the bone and cause infection. Infection can develop around a pin or screw site (Fig. 35-6). Most pin tract infections are minor if treated appropriately with antibiotics and good wound care around the hardware.13 Incidence of pin tract infections is considered to be infrequent, ranging from 0.5% to 21%.13–19 External fixation may have a higher rate of infection than internal fixation.19 Most infections from pins and screws are minor and do not lead to significant osteomyelitis if treated early. However, this infection can necessitate the early removal of hardware and can result in necrosis of the bone if the infection cannot be controlled.13,16

Infections

General Principles

Markings on forearm indicate progressing erythema and edema. (Courtesy of Dr. James Nappi, Hand & Microsurgery Associates, Columbus, OH.)

Anatomy and Pathology

Perionychium

Paronychia

Eponychia

Felon

Flexor Sheath Infection

Fascial Space Infection

A, Potential spaces of the mid palm. B, Thenar space abscess. C, Midpalmar space abscess. (From Stevanovic MV, Sharpe F: Acute infections. In Wolfe SW, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al, editors: Green’s operative hand surgery, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.)

Osteomyelitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Infections