Indications for Metal on Metal Resurfacing

Andrew A. Shinar

Gregory G. Polkowski

Jeffrey B. Stambough

Ryan M. Nunley

Case Presentation

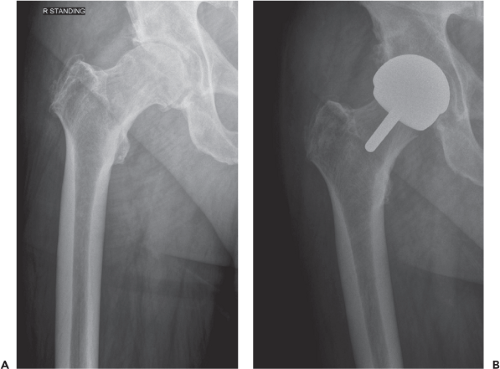

This 50-year male manager of student athletics complained of 3.5 years of left groin pain, which eliminated running sports from his life. He tried to remain reasonably active and had a Harris hip score of 68. Physical examination demonstrated a fit 6-ft, 200-pound man with a moderate limp, equal perceived leg lengths, and painful limited rotation of his left hip. Multiple surgical and nonoperative treatments were offered to the patient, and he chose surgery 6 months later. His preoperative x-rays (Fig. 67.1) showed severe degenerative joint disease.

Introduction

When surgeons consider indications for modern metal-on-metal (MoM) hip resurfacing, they vary from never recommending this procedure (1,2) to using it for most hip arthroplasties they perform (5,6). Many surgeons, however, have never performed a hip resurfacing arthroplasty (HRA) as it requires extra training, and they are further dissuaded by the higher failure rate that will likely occur along their learning curve (3,4,7). The lack of clear-cut evidence claiming resurfacing’s superiority in functional recovery to total hip replacement for certain populations (8,9) further convinces many surgeons that it is not worth the extra training.

Figure 67.1. Preoperative AP pelvis radiograph demonstrating severe osteoarthritis of the left hip. (Images courtesy of Dr. Craig Della Valle, MD.) |

While resurfacing arthroplasty has historically been advocated and performed by a select group of surgeons, a surge in popularity of HRA was seen shortly after approval of one device in 2006. The popularity of HRA has diminished greatly in the United States as mid- and long-term data have become available, underscoring surgeon concerns for possible higher early failure rates and heightened fears with the long-term effects and complications associated with MoM-bearing surfaces. In spite of these issues, thousands of HRAs are still performed annually in the United States. With time, the indications for resurfacing have been refined to account for at-risk populations and the failure mechanisms seen during the initial phase of popularity of this procedure. In this chapter we will address the indications for HRA by exploring several aspects of the patient selection process and surgical decision making that allow for the successful execution of this procedure.

General Considerations

Theoretical advantages of resurfacing arthroplasty include bone preservation, less complicated revisions, and physiologic maintenance with improved gait patters (10). It is safe to say however, that some surgeons are dissuaded by studies that highlight the poor results with revisions of surface replacement (11,12,13,14,15), which would eliminate the temporizing appeal of the procedure. Moreover, results have differed between studies involving small numbers of surgeons and those composed of registries, with more failures occurring in the registry studies (16).

This fact suggests that the surgery might be best left to those with a great deal of experience with it (17). Other

surgeons, however, have had remarkable success in many different patient groups with hip resurfacing, and have seen their active patients recover quickly and return to high levels of activity (18). Better training before embarking on surface replacement may improve the learning curve (19) and better patient selection has improved outcome (4,20,21,22). Further, choosing the implant with the best track record can improve patient outcomes (23). It can be argued that for select populations, hip resurfacing has better outcomes than total hip replacement (24). Choosing surface replacement for these patients and avoiding it in at-risk populations is likely the optimal application of HRA. And while not all revision results have been negative, the procedure may temporize hip symptoms for a prolonged period in circumstances not dominated by metal ion reactions (12,25,26).

surgeons, however, have had remarkable success in many different patient groups with hip resurfacing, and have seen their active patients recover quickly and return to high levels of activity (18). Better training before embarking on surface replacement may improve the learning curve (19) and better patient selection has improved outcome (4,20,21,22). Further, choosing the implant with the best track record can improve patient outcomes (23). It can be argued that for select populations, hip resurfacing has better outcomes than total hip replacement (24). Choosing surface replacement for these patients and avoiding it in at-risk populations is likely the optimal application of HRA. And while not all revision results have been negative, the procedure may temporize hip symptoms for a prolonged period in circumstances not dominated by metal ion reactions (12,25,26).

Further complicating the picture is the evolving adverse outcomes with MoM articulations seen in total hip replacement due to increased metal ion debris and the surrounding reactive tissue (22,28). MoM hip resurfacing has endured some of these complications, especially in younger, female patients (29,30). In terms of revision for pseudotumors, resurfacing in males has done much better than MoM hip replacement in young male patients or versus female patients with resurfacings (30,31). This tendency could be due to the fact that resurfacing is associated with lower serum levels of metal ions (8). The problems with MoM articulations in general are considered to be lower in hip resurfacings than in stemmed implants with large MoM heads, which is probably related to the lack of a modular junction and corrosion occurring between the modular femoral head and stem (32).

The decision to proceed with hip resurfacing over hip replacement will depend on a number of factors. The underlying diagnosis of hip disease, morphology of the proximal femur, and the gender and age of the patient can guide decision making. One study found that poor bone quality or deformity eliminated half of the patients from consideration of hip resurfacing in a group of patients less than 50 years of age (33). Inability to increase offset and leg length in circumstances where it is desirable can further limit indications (34).

Other considerations include whether hip resurfacing has an improved or equal recovery, function, longevity, and complication profile, and for which groups of patients these factors remain advantageous. Complications that can differ with hip resurfacing include adverse local tissue reactions secondary to bearing surface wear, dislocation, leg-length discrepancy, peri-implant fractures, and loosening. We will examine these risks among specific patient groups.

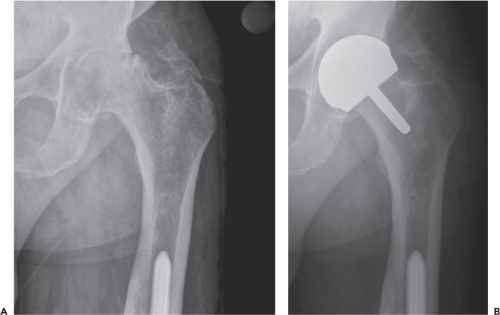

The ideal candidates for hip resurfacing are younger men with osteoarthritis, large femoral head size, and good proximal bone stock (5,31,35). Those with high expected activity levels are often chosen for hip resurfacing, as are those with offset issues (Fig. 67.2) or retained hardware

(Fig. 67.3) that could make conventional total hip arthroplasty more difficult due to exposure and anatomic concerns. Patients with large avascular necrotic lesions, large femoral cysts, or other femoral head deformities such as coxa vara, and substantial leg-length discrepancy (with a desire to correct it) are relatively contraindicated for HRA. In general, elderly patients, patients with low activity, and women (or men) with small femoral head sizes are contraindicated. Special contraindications for MoM hip resurfacing include metal sensitivity, renal impairment, and women of child-bearing age as chromium and cobalt ions do appear to cross the placenta, albeit at lower levels than those seen in the maternal serum (36). The usual THR contraindications of active infection or substantial medical debility likewise apply.

(Fig. 67.3) that could make conventional total hip arthroplasty more difficult due to exposure and anatomic concerns. Patients with large avascular necrotic lesions, large femoral cysts, or other femoral head deformities such as coxa vara, and substantial leg-length discrepancy (with a desire to correct it) are relatively contraindicated for HRA. In general, elderly patients, patients with low activity, and women (or men) with small femoral head sizes are contraindicated. Special contraindications for MoM hip resurfacing include metal sensitivity, renal impairment, and women of child-bearing age as chromium and cobalt ions do appear to cross the placenta, albeit at lower levels than those seen in the maternal serum (36). The usual THR contraindications of active infection or substantial medical debility likewise apply.

Surgeon Issues

Training

The choice to proceed with a resurfacing over a conventional hip replacement must take into account one’s training. Shimmin reported from the Australian Registry failure rates of 5.8% at 4 years if one’s hospital performed fewer than 50 hip resurfacings per year, 4.7% if it performed between 50 and 100, and only 2.7% if it performed more than 100 (17). He reported that it would take a surgeon 50 resurfacings to reach a level of experience commensurate with a low failure rate, and 13 cases to get halfway there. Similarly, Mont reported 11 failures in his first 50, as compared to one failure in his next 50, and then two failures in all cases beyond his first 100. One can argue, though, that these same effects are seen in hip replacement as well, with the learning curve occurring during residency rather than in independent practice. Further, Katz et al. (37) have demonstrated similar volume-related findings to those in the Australian Registry, regarding hip replacements. Both procedures are technically demanding and show superior results when performed by surgeons and hospitals with more experience.

A surgeon well trained in resurfacing of the hip can confidently choose this procedure for male patients under 65, as survival has been comparable so far to conventional hip replacement, and may be better in the long term. With the information available,

it is difficult to prove a substantial difference in functional outcome when hip resurfacings are compared to large diameter head hip replacements. Hip resurfacings do have better ion levels when compared to this group. When resurfacings are compared to smaller head hip replacements, though, randomized trials do tend to show better function in resurfacing but not exceptionally so. Hip replacements likely have a higher risk of dislocation when traditional head diameters are used, and fear of dislocation in these circumstances may prevent greater activity with hip replacement. With the information available, hip resurfacings better replicate leg lengths and offset. Femoral neck fracture, which will be discussed below, is a complication unique to hip resurfacing, but is rare when the procedure is performed in younger males and by experienced surgeons.

it is difficult to prove a substantial difference in functional outcome when hip resurfacings are compared to large diameter head hip replacements. Hip resurfacings do have better ion levels when compared to this group. When resurfacings are compared to smaller head hip replacements, though, randomized trials do tend to show better function in resurfacing but not exceptionally so. Hip replacements likely have a higher risk of dislocation when traditional head diameters are used, and fear of dislocation in these circumstances may prevent greater activity with hip replacement. With the information available, hip resurfacings better replicate leg lengths and offset. Femoral neck fracture, which will be discussed below, is a complication unique to hip resurfacing, but is rare when the procedure is performed in younger males and by experienced surgeons.

Patient Groups

Young Men

Much of the registry data confirms that young men with good bone stock and large femoral heads are ideal candidates for hip resurfacing. Data from the British National Joint Registry have demonstrated that men younger than 60 experience a greater than two times less revision risk than the rest of the population (23). Further results from the Australian Registry confirm these sentiments. At 7 years, men below the age of 65 demonstrated better survival than any other group receiving resurfacing, and better longevity than men in this age group receiving total hip replacement—4.2% versus 4.6% revised at 7 years for those less than 55 (38). This group in particular has a low risk of femoral neck fracture and has high activity levels that could accelerate wear of softer articulations typical in standard hip arthroplasty.

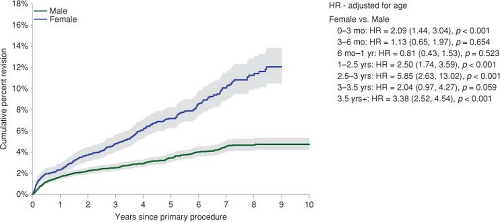

When considering only gender, men have shown better survival than women with hip resurfacing at 7 years in the Australian Registry, with revision of 4.5% versus 10.1% (Fig. 67.4). Older men, however, do worse than younger men, with a revision rate of 6.5% for those 65 and older, and 4.2% and 4.3% for the younger age groups (39). In terms of complications related to gender and age differences, Glyn-Jones et al. (40) found a pseudotumor rate of 0.5% in males younger than 40, 6% in women over 40, and 13.1% in women less than 40.

Elderly Patients

As mentioned, in the Australian Registry, men over 65 with resurfacings are revised at a rate of 6.5% at 7 years. Total hip replacements do significantly better in this age group with rates of 4.4% and 4.6% at 7 years, for those between 65 and 75 and those over 75, respectively. Hip resurfacings in younger age groups do better than in the elderly. The age groups of <55 and those between 55 and 65 have had similar results, with revision rates at 7 years of 4.2% and 4.3%, respectively. This difference is almost statistically significant, versus elderly patients.

Resurfacing is generally not performed in elderly women, as the femoral neck fracture rate is elevated in this potentially osteoporotic group with smaller femoral necks. Shimmin and Back (41) found a rate of 0.98% of femoral neck fractures in men in the Australian Registry in 2005, and a doubling of the rate to 1.91% in women. Interestingly the average age of the women was only 56 years, while that of the men was 62 years.

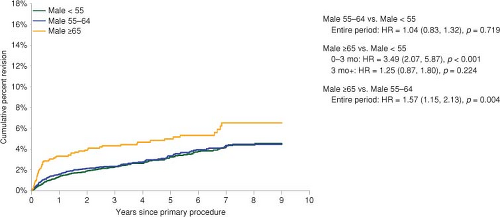

Complications were also found to be higher among the more elderly patients in the initial American experience with hip resurfacing (19). McGrath et al. (42) acknowledged the less-optimal results among elderly patients in registries, but found that in matching their patients over 60 with those under 60, there was no significant difference in revision rate, radiographic failures, or functional score outcome. From the Australian Registry, it appears that once the initial increased failure rate is surpassed, the subsequent yearly failure rate

is similar between males older than 65 and those younger (Fig. 67.5).

is similar between males older than 65 and those younger (Fig. 67.5).

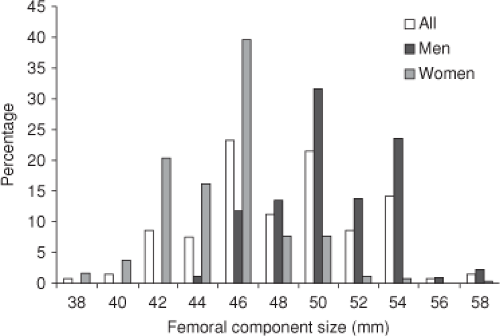

Women with Large Femoral Heads

The issue of head size is more important when considering females for hip resurfacing. It is less important with male patients as a great majority have sizes of femoral head adequate to avoid bearing surface complications (40). Seventy percent of the females in Glyn-Jones’ study had femoral heads 48 mm in size or smaller, as compared to 9% of the males (Fig. 67.6). They could find no definitive cut-off value of head size, but found that those with femoral heads below the average size for their gender had a fivefold increase in risk for adverse local tissue reactions.

The report of Pandit et al. raised the issue as to whether female gender was responsible for the soft tissue masses seen in their patients, as all patients developing these masses were women. A gender specific immune difference or a differential exposure to jewelry could possibly explain this phenomenon. Two factors, however, are more likely confounding variables. As above, women receiving hip resurfacing generally have smaller head sizes than men, and more women have the diagnosis of dysplasia. The smaller head size may prevent fluid film formation, which would increase wear and the propensity for lymphocyte-mediated reactions. Dysplasia, which is more common in women, could cause placement of both components in more anteversion and the acetabulum in more abduction, creating a tendency to edge load the bearing surface, thus increasing wear and the risk for wear-related problems. Implants associated with soft tissue masses have indeed shown wear patches consistent with edge loading (43). Further, dysplastic patients tend to have smaller head sizes.

In reviewing only female patients with hip resurfacing, the Australian Registry has found head size much more than female gender to be the predetermining factor when it comes to survivorship. Both men and women with head sizes less than 50 mm did poorly, the men being revised at a rate of 9.3% at 7 years, and women with heads less than 50 mm with a rate of 11.2%. Similarly, the curve for women with larger heads (50 mm or greater) corresponds closely to the curve for men with larger heads up to 7 years, with revision rates of only 3.5% and 3.7%, respectively (Fig. 67.7 and Table 67.1). Only 13.7% of the women, however, received a head 50 mm or larger, whereas 83.8% of men did so. It appears from this data that in the unusual circumstance of a female femoral head being large enough to accommodate a 50 mm or greater head, there is no contraindication to hip resurfacing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree