CHAPTER 24 Indications and Contraindications

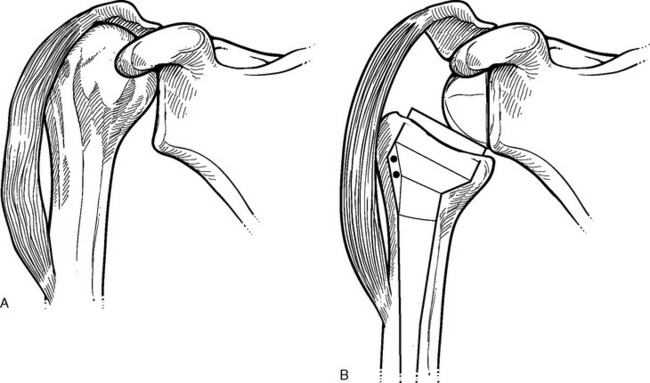

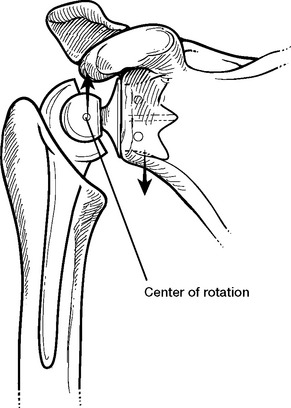

Reintroduction of reverse-design shoulder arthro-plasty has added a powerful device to the shoulder surgeon’s armamentarium. Reverse ball-and-socket shoulder prostheses were initially introduced in the 1960s to treat patients with glenohumeral arthritis and massive rotator cuff tears. The concept of these and subsequent devices is to resolve upward migration of the humeral head and thereby restore the normal deltoid moment arm. This allows the deltoid to power active elevation of the arm (Fig. 24-1). The problem with the initial designs was early loosening of the glenoid caused by the action of deltoid forces on the laterally offset center of glenohumeral rotation (Fig. 24-2). These failures eventually resulted in abandonment of these early prosthetic designs.

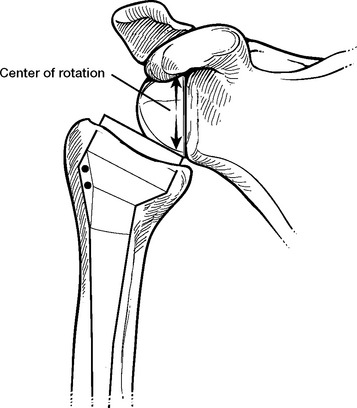

Figure 24-2 Forces acting on the glenoid fixation causing loosening of early reverse prosthetic designs.

In 1987, Paul Grammont introduced a reverse-design prosthesis that used a “glenosphere” component fixated over the scapular neck. In an effort to overcome the failures that had plagued earlier attempts, Grammont’s design placed the center of glenohumeral rotation within the bone of the glenoid instead of lateral to it (Fig. 24-3).1 Most available reverse prostheses take advantage of Grammont’s ingenuity.

ROTATOR CUFF TEAR ARTHROPATHY (GLENOHUMERAL OSTEOARTHRITIS WITH MASSIVE ROTATOR CUFF TEAR)

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy was initially described by Neer and consists of a massive irreparable rotator cuff tear combined with glenohumeral arthritis and, in the late stages, humeral head osteonecrosis.2 This entity has gradually expanded to include all patients with massive rotator cuff tears and glenohumeral arthritis, even in the absence of humeral head osteonecrosis. Although we believe that rotator cuff tear arthropathy as described by Neer and glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a massive rotator cuff tear are two distinct entities, the clinical scenarios are sufficiently similar that we consider them together both in our practice and in this textbook.

Rotator cuff tear arthropathy (glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a massive rotator cuff tear) is the single most common indication for which we per-form reverse shoulder arthroplasty. This indication accounts for nearly half of our cases of reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Clinical Findings

Testing of the individual rotator cuff tendons will typically demonstrate obvious insufficiency. Rotator cuff insufficiency may involve the posterior superior rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor), the anterior superior rotator cuff (supraspinatus, subscapularis), or the entire rotator cuff. Additionally, the long head of the biceps tendon is often ruptured, as demonstrated by the characteristic deformity of the upper part of the arm. Chapter 7 details clinical testing of the rotator cuff.

Imaging Findings

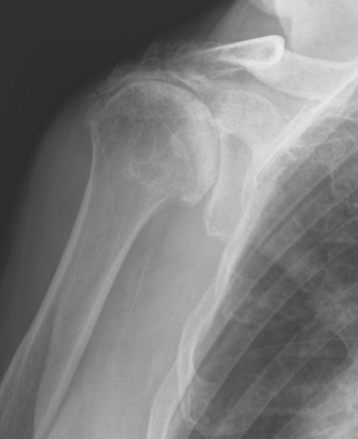

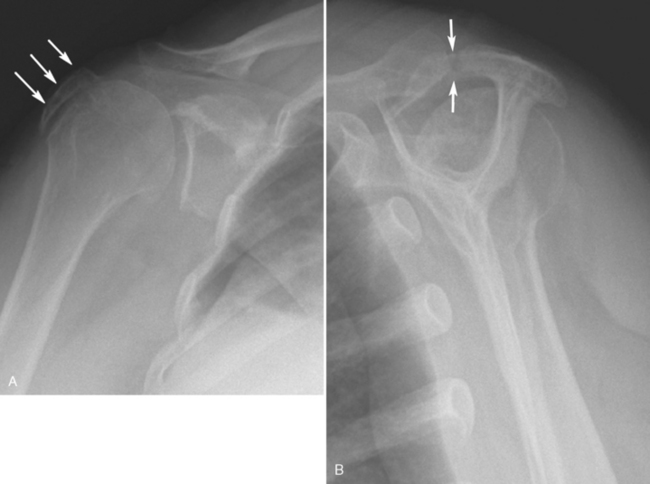

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space. Humeral head osteophytes may or may not be present. Static migration of the humeral head is almost always present. In patients with insufficiency of the posterior superior rotator cuff, the humeral head migration occurs in a superior direction (Fig. 24-4). In patients with insufficiency of the anterior superior rotator cuff, static anterior migration may be apparent on just the axillary radiograph (Fig. 24-5). Less frequently, the patient may demonstrate only dynamic migration of the humeral head as a result of rotator cuff insufficiency. Acromial changes on radiographs of patients with no apparent static superior humeral head migration may show evidence of this dynamic instability (Fig. 24-6). Patients with osteoarthritis and a massive rotator cuff tear will frequently have osseous wear on the undersurface of the acromion, on the superior glenoid, or on both (Fig. 24-7). Less frequently, insufficiency fractures of the acromion may be caused by wear (Fig. 24-8). These stress fractures, however, do not contraindicate use of a reverse prosthesis.

Figure 24-8 A and B, Insufficiency fracture of the acromion (arrows) in a patient with rotator cuff tear arthropathy.

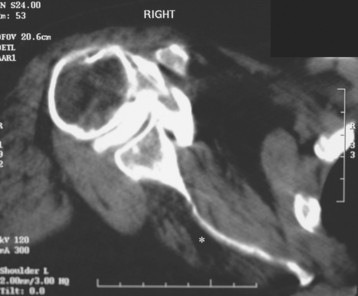

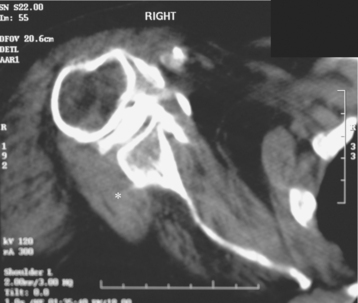

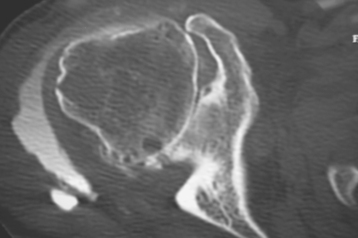

Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging) will always show rotator cuff tears involving more than one tendon (Fig. 24-9). The rotator cuff muscle belly of the torn tendons shows fatty infiltration (Fig. 24-10). In cases with long-standing rotator cuff tears involving the infraspinatus in which the teres minor is intact, the teres minor muscle belly may demonstrate compensatory hypertrophy (Fig. 24-11).

Figure 24-9 Computed tomographic arthrogram demonstrating a massive rotator cuff tear with glenohumeral arthritis.

Secondary imaging studies can confirm osseous wear (glenoid, acromion) in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis and a massive rotator cuff tear. Coronal sections of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging have been used to classify superior glenoid wear (Fig. 24-12).3

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (INFLAMMATORY ARTHROPATHY) WITH MASSIVE ROTATOR CUFF TEAR

More than 10% of patients considered for shoulder arthroplasty with an underlying diagnosis of rheu-matoid arthritis have a large tear of the rotator cuff that contraindicates unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty.4 These patients are candidates for either reverse shoulder arthroplasty (our preferred treatment) or unconstrained hemiarthroplasty (our preferred treatment only in cases of severe osseous insufficiency).

Clinical Findings

Clinical findings in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a massive rotator cuff tear include glenohumeral crepitus and stiffness. Acromiohumeral crepitus may be present. Testing of the individual rotator cuff tendons will typically demonstrate obvious insufficiency. The rotator cuff insufficiency may involve the posterior superior rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor), the anterior superior rotator cuff (supraspinatus, subscapularis), or all of the rotator cuff tendons. Additionally, the long head of the biceps tendon is often ruptured, as demonstrated by the characteristic deformity of the upper part of the arm. Chapter 7 details clinical testing of the rotator cuff.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree