Index Pollicization for Congenital Absence and Hypoplasia of the Thumb

Joseph Upton

INTRODUCTION

During the past five decades, no area of hand surgery has changed as much as thumb reconstruction. Techniques for reconstruction following traumatic total or subtotal loss with the transposition of an index or other digit were introduced and refined after the World War II era. Many ingenious methods of pollicization were introduced as basic principles evolved. The introduction of microvascular techniques has made the reattachment of amputated parts the procedure of choice following most traumatic injuries and, as such, has greatly reduced the need for posttraumatic pollicization.

Despite our enthusiasm for microvascular applications in hand surgery and a plethora of new techniques, index pollicization remains the procedure of choice for congenital absence and severe hypoplasia of the first ray. The early contributions of Gosset, Hilgenfeld, and Bunnell in the treatment of traumatic loss were later refined for the child with congenital differences by Littler and Buck-Gramcko. Over the past 25 years, we have built upon this foundation and added further adaptations in a series of 270 pollicization procedures.

INDICATIONS

Thumb Hypoplasia and Absence Deformities

Any child with severe bilateral absence or hypoplasia of the thumb (types IIIB, IV, and V) is an excellent candidate for pollicization, barring any accompanying major neurologic, cardiovascular, or hematologic deficiency that would prevent the child from using the upper extremity effectively. Most experienced surgeons would recommend this procedure for unilateral absence or hypoplasia as well. Those with severe mental retardation or proximal limb deficiencies, such as shoulder-tohand phocomelia, may not be good candidates. Important initial considerations in these patients include the motion status of the shoulder and elbow, as well as the arm and forearm length, all of which determine the position of the hand and arm in space. The child must be able to use her/his new thumb effectively to justify this procedure. Additional indications include the rare mirror hand, five-fingered hand, and other unique malformations.

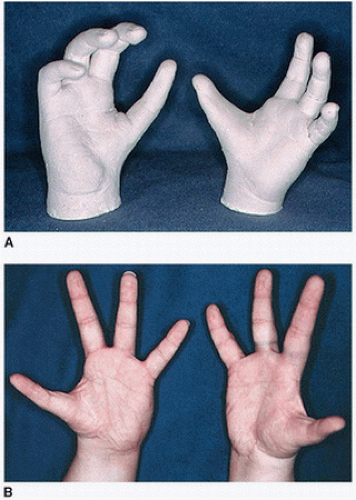

Aesthetic Indications

The importance of appearance has been long overlooked by authors of congenital hand texts. Older children, and particularly teenagers, prefer a one-thumb, three-fingered hand to the four-fingered hand with or without the abducted and slightly pronated index finger. When the normal or slightly stiff index finger has been repositioned as a thumb early in life, all children will adapt and use this ray effectively as a thumb. Creation of a deep, broad first web space, and the size of the intrinsic muscles on the radial side of the thumb, are key variables that impact the final appearance of the new thumb, which, distally, will always be thinner than the normal thumb.

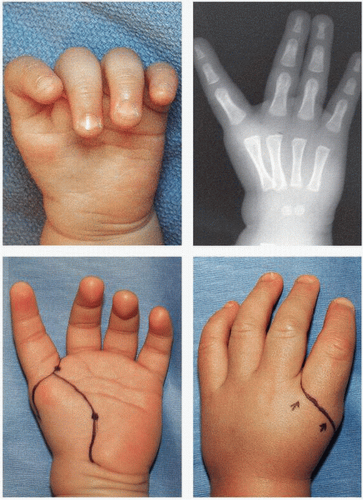

Type IIIB Thumb

The decision to ablate a good-looking thumb with large phalangeal components and a deficient metacarpal (MP) with no carpometacarpal (CMC) joint is difficult for parents in most cultures. In our experience, these families are usually members of strict religious groups and believe that God put it there for a reason. However, many of these patients have bilateral, asymmetrical malformations. It is best to pollicize the most normal index digit first so that the parents may become encouraged by the early outcome and agree to have the same procedure on the opposite hand (Fig. 34-1). However, it is not always possible to convince some parents, who will doctor shop until they find a surgeon willing to build upon the existing hypoplastic thumb. Stabilization of the deficient thumb MP with bone or tendon grafts followed by tendon transfers can be completed in multiple stages. Microvascular transfer of the second toe MP joint with overlying soft tissue to reconstruct the new thumb CMC joint has also been performed in these thumbs. The long-term outcomes have been less satisfactory than a well-performed index pollicization. All experienced pediatric hand surgeons prefer the index pollicization to microvascular alternatives for these indications.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Children with severe associated malformations, especially neurologic, with little chance of function should not be subjected to this additional operation. However, these bedridden patients should be distinguished from those ambulatory children with mild retardation who use their arms and hands

adroitly in their activities of daily living. All cases must be individualized, as there are very few absolute contraindications for this procedure.

adroitly in their activities of daily living. All cases must be individualized, as there are very few absolute contraindications for this procedure.

Those with radial deficiencies have a smaller, stiff, often-contracted index ray and are not good candidates for a formal index pollicization. Judicious rotation-recession osteotomy of the index ray with and without joint arthrodeses is often preferred.

In some cases of thumb hypoplasia, the remaining elements are severed enough to initiate augmentation instead of pollicization. Despite the intellectual appeal of maintaining a five-digit hand, reconstruction of some of their type IIIA thumbs is demanding, and results are often inferior to pollicization.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Physical Examination

A careful physical examination is often all that is necessary to adequately assess these hands. These patients usually fall into two major groups: those with a normal index finger and good thenar muscles and those with radial dysplasias, previous centralizations, and stiff index rays. A detailed documentation of active and passive range of motion, the presence and strength of intrinsic muscles, and flexion contractures of the index and/or other digits should be carefully recorded. Videotapes provided by occupational therapists are very helpful for evaluations of older children and all postoperative patients.

Radiology

Routine anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs are obtained. Angiograms are obtained only on limbs with unusual anomalies, such as the mirror hand or other bizarre malformations in which the arterial blood supply to the index digit may be in question.

Parents and Family

Often, the surgeon’s hardest job is to counsel discriminating parents who have carefully watched their child adapt to every task presented. The use of pre- and postoperative hand molds, photographs of other patients, and actually meeting other patients who use their new thumbs are quite useful. It is very important to give the parents of these children an accurate expectation of the postoperative outcome and to emphasize the diminished pinch and grasping ability of these new thumbs. These new thumbs will never be normal, but the final outcome will be better than those achieved with alternative reconstructions.

Timing of Pollicization

Some controversy will always exist regarding the optimal time for an index pollicization. Although some experienced surgeons such as Dieter Buck-Gamcko and Guy Fouchet have performed these operations on children less than 4 months of age, most wait until the child is between 12 and 24 months of age. Pollicization in a 12-month-old toddler is much easier than that in a 2- to 3-month-old baby. I have found that the size of the hand and not the chronologic age of the child is the primary consideration. Other advantages of waiting include improved cooperation of the child and increased likelihood of performing a much more precise operation on a larger hand. The 1- to 2-year age range is also preferable with our limited knowledge of neuromuscular maturation and central conditioning and plasticity of the cerebral cortex.

SURGERY

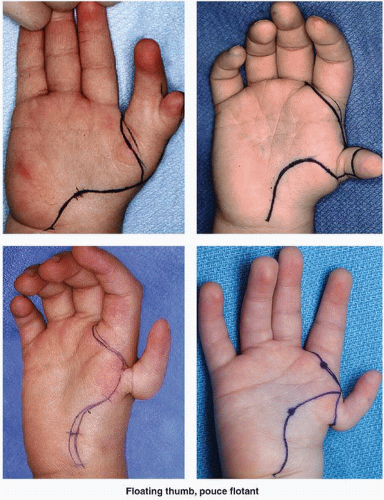

Incisions

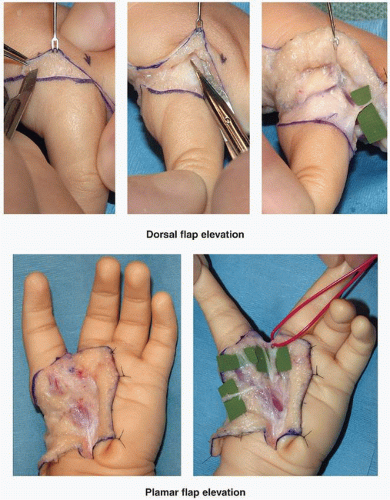

In contrast to posttraumatic thumb reconstructions, adequate skin cover is present in congenital cases, and the need for skin grafts is usually a reflection of poor incision planning. A racquetshaped incision is made across the base of the thumb 1.0 to 2.0 mm proximal to the digitopalmar flexion crease. The radial extension of this incision may extend either toward the palm or directly along the radial border of the hand (Figs. 34-2 and 34-3). Once this incision is made through the dermal layer, upward traction of the skin will enhance the decompression of the fibrous septae, anchoring the skin to the palmar aponeurosis. If this dissection is kept above the palmar fascia,

there is no danger of neurovascular injury. The palmar aponeurosis should not be elevated with the flap (Fig. 34-4, bottom).

there is no danger of neurovascular injury. The palmar aponeurosis should not be elevated with the flap (Fig. 34-4, bottom).

The dorsal incision extends over the index finger at the MP joint level. In most children, two large dorsal veins can be located on either side of the dorsal midline. Once the tight dermal layer has been penetrated, upward traction of the skin flap will enable both sharp and blunt scissor dissections between the two layers of fat on the dorsal surface of the hand. The important dorsal veins and nerves are located between these two layers, which may not be anatomically distinct but which are easily separated with proper retraction (Fig. 34-4, top). If the surgeon retains a generous layer of fat on the dorsal flap, the blood supply to this region will not be compromised. The dorsal flap is raised three to four centimeters proximal for visualization of the venous drainage plexus and to allow ligation of branch(s) to the long finger, which, if left intact, will tether full proximal movement of the digits later in the procedure (Fig. 34-4).

One of the most important functions of these incisions is the creation of a normal-appearing first web space, which means extending the level of the web on the ulnar side of the new thumb to the MP joint, formerly the index proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. This is accomplished by advancing tissue from the ulnar side of the new thumb into the new web space. The dorsal cutback incision, which permits this advancement and is delayed until the precise location of the incision, can be made later in the operation.

Incisions: Types IIB and IV

Small nonfunctional thumbs attached by diminutive soft-tissue pedicles should be ablated in the newborn nursery. The larger, hypoplastic thumb is usually saved until a later decision can be made in regard to its usefulness. There is no standard method for the introduction of this tissue. It is best to plan incisions first as though there were no thumb remnant, and then, one can incorporate the extra tissue into the original design (Figs. 34-3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree