A COGNITIVE MODEL OF HYPOCHONDRIASIS

The main tenant of the cognitive model is that the disorder results from, and is maintained by, the misinterpretation of normal bodily signs and symptoms as a sign of serious organic pathology. This is similar to the process which is central in the cognitive model of panic. However, the misinterpretations in panic tend to differ from those in health anxiety in a fundamental way that reflects the patient’s perceived time course of the appraised catastrophe. More specifically, panickers tend to believe that the catastrophe is immediately impending during a panic attack while health-anxious individuals believe that the catastrophe (e.g. death or painful suffering) will occur at some time in the more distant future. When the catastrophe is appraised as immediate, panic attacks may be more likely to occur.

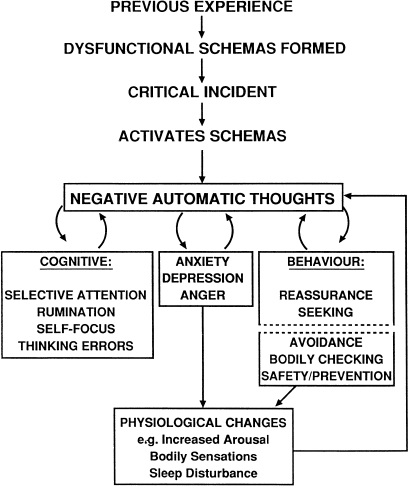

Salkovskis and Warwick are leading proponents of the misinterpretation model of health-anxiety (Salkovskis, 1989; Warwick & Salkovskis, 1989, 1990). In their model individuals are considered to develop hypochondriasis when critical incidents activate dysfunctional assumptions concerning health. These assumptions may form early or later in life but are modified through ongoing experience.

The critical incident may be the experience of unexpected physical symptoms, noticing previously unnoticed bodily signs, the death of a relative or exposure to illness-related information. Once activated these beliefs lead to the misinterpretation of bodily sensations/signs as evidence of serious physical pathology. These misinterpretations occur as negative automatic thoughts, which may involve vivid negative images. In health anxiety these images typically consist of parts of the body ‘giving-out’ or functioning improperly. For example, patients report images of the heart quivering, the lungs only partially inflating, the brain haemorrhaging, and cancer ‘taking over’ the body. In consequence, a number of related mechanisms are activated which are involved in the maintenance of health preoccupation and anxiety. Four categories of maintenance mechanism are distinguished; cognitive, affective, behavioural, and physiological. A cognitive model of hypochondriasis based on Warwick and Salkovskis (1989) depicting a relationship between these mechanisms is presented in Figure 6.0.

Figure 6.0 A cognitive model of health anxiety (adapted from Salkovskis, 1989; Warwick & Salkovskis, 1990)

Cognitive factors

Selective attention processes in health anxiety may resemble those found in panic disorder. For example, there is typically an increased focusing on internal bodily processes such as heart rate, gastro-intestinal activity, swallowing, breathing and so on. In addition, some health-anxious patients focus on the outwardly observable aspects of their bodies and are hypervigilant for signs such as asymmetry of the body, bumps and blemishes on the skin, hair loss or irregular hair growth, and pupil size. Preoccupation with products expelled from the body such as the colour of one’s saliva, faeces and urine may also be present. In these latter cases patients are often checking for noticeable changes in functioning such as the presence of blood colorations. Aside from selective attention to the body, attentional bias for external negative illness-related information is also common. This may take the form of increased sensitivity to particular types of information during clinical consultation and enhanced awareness of external illness information presented in the media. Rumination in the form of worry or mental ‘problem solving’ is a common feature in some cases. Worry about health may be a manifestation of a hypervigilant strategy adopted by the individual so that early signs of illness may be detected, or may be a superstitious strategy intended to ward off dangers of positive thinking (Wells & Hackmann, 1993). Continued rumination about health maintains bodily awareness and contributes to affective symptoms (e.g. sleep disturbance), factors that can contribute to misinterpretation.

Common cognitive distortions (thinking errors) in health anxiety are: discounting of alternative non-serious explanations of symptoms, selective abstraction, and catastrophising. A tendency to discount medical feedback and the results of investigations that fail to find illness may result from particular beliefs, such as: ‘It is possible with the appropriate tests to know with certainty that one is not ill.’ Selective abstraction is a distortion that operates in clinical consultations, it consists of placing undue emphasis on, and taking out of context minor bits of information. For example, the health-conscious patient may be given feedback that his/her blood pressure is ‘within the normal range and should be checked again at a later date’. The idea of repeating the check may be taken out of context and used to infer that there is something seriously wrong that needs monitoring. Catastrophising involves overinflating the significant of signs and symptoms and is often accompanied by a failure to consider benign explanations for them.

Affect/physiological changes

The affective response which accompanies misinterpretations is typically anxiety (although depression is often a secondary feature of longstanding health preoccupation). Autonomic symptoms of anxiety are commonly misinterpreted symptoms in health anxiety. Changes in bodily processes such as bowel function, heart rate, and change in sleep patterns resulting from arousal may be misinterpreted.

Behavioural responses

Several behavioural factors contribute to the maintenance of misinterpretations in health anxiety: checking, avoidance, safety behaviours, reassurance seeking.

Repeated checking of the body such as palpation of the abdomen to check for discomfort, or self-examination such as checking for rectal bleeding, or repeated checking for breast or testicular lumps can lead to soreness and tissue trauma. Discomfort resulting from checking behaviours is likely to be misinterpreted as further evidence of serious physical illness. Even in the absence of physical damage, bodily checking maintains awareness of the body so that normal and benign symptoms are more easily noticed—a perceptual change that can be falsely interpreted as evidence of worsening symptomatology rather than of increased attention. Other examples of bodily checking contributing to physiological changes include repeatedly taking deep breaths to check that the lungs are functioning properly, which can produce muscular strain and chest discomfort; forced swallowing to check for feared anomalies in the throat, which typically makes swallowing seem more difficult; and checking one’s pulse, which increases awareness of its natural variability.

Avoidance behaviour takes several forms. Avoidance may be of certain activities such as strenuous physical exertion, or avoidance of situations which activate health rumination and anxiety such as exposure to media material about illness. In some instances the health-anxious patients will try not to think about illness by attempting to control their thoughts or by distraction. Avoidance of ‘risky’ behaviours such as physical exertion prevents exposure to disconfirmatory experiences, and avoidance behaviours maintain preoccupation with concepts of illness. Attempts to suppress thoughts may be problematic because that leads to a paradoxical increment in unwanted thoughts (see Chapter 8).

A third type of behaviour tied to problem maintenance is the patient’s use of safety behaviours. Specific safety behaviours in health anxiety are intended to reduce the risk of illness in the future. In particular, these are ‘preventative’ behaviours. For example, a patient with cardiac concerns may take an aspirin each day, or vitamin supplements are used on a daily basis when there is no medical reason to do so. In moderation these particular behaviours may not produce problematic bodily responses, however they serve to maintain preoccupation with illness and health concepts, and are capable of maintaining beliefs such as one’s body is weak and needs all the assistance available to remain healthy. Other precautionary responses, such as extensive resting, can be problematic because they contribute to loss of physical fitness and body strength. These symptoms may then be taken as further evidence of serious illness. Some safety behaviours consist of adopting particular bodily postures or controlling bodily responses such as swallowing or breathing. These behaviours maintain bodily-focused attention and intensify symptoms.

Repeated reassurance seeking is the fourth behaviour to be considered in the conceptual analysis of factors responsible for maintaining dysfunctional belief at the misinterpretation and schema levels. Reassurance can be sought in different ways; reassurance seeking behaviours are often subtle and may involve asking a partner or family members about symptoms, or it may involve persistently mentioning and describing symptoms to others. Reassurance seeking may consist of visits to the doctor and requests for investigations and tests. Reassurance seeking can manifest itself in the form of studying medical articles and books in an attempt to self-diagnose and rule-out serious illnesses.

A number of problems exist with reassurance seeking. One of the more salient problems is that conflicting or inconsistent information is given about symptoms, and after repeated presentations to medical professionals patients may feel that they are not being ‘taken seriously’. These factors are capable of strengthening a patient’s desire for further investigations and contribute to the development of negative beliefs about medical competency so that failure to find a physical cause of symptoms provides little comfort.

Summary of model and new directions

In summary, the cognitive model of health anxiety maintains that misinterpretation of bodily signs and symptoms and the physiological/affective, cognitive, and behavioural factors (checking, reassurance seeking, avoidance and safety) associated with them are involved in the aetiology and maintenance of the disorder. The model asserts that individuals misinterpret symptoms partly because of the assumptions and beliefs that are held about the meaning of bodily events. Recent work by Wells and Hackmann (1993) has explored in detail images and associated beliefs in health-anxious and panic patients. For some individuals illness has extremely negative and sinister implications. In these cases there is a strong fear of death and images and beliefs that death will be an experience of external distress or punishment. In other cases there is an inherent concept that following death there will be a continuation of awareness, but this is an awareness of the things that have been left behind. In other cases a key belief is that illness will lead to a change in ability to work or function, and when this is an important determinant of self-esteem there is a predicted diminution in self-concept. Beliefs about death and spiritual concepts (‘meta-physical’ beliefs) may interact with more general negative beliefs about the self in contributing to a fear of illness, and of death.

GENERAL TREATMENT ISSUES

There are two general issues that should be considered in implementing effective cognitive therapy for health anxiety. The first deals with the precise aim of treatment for this disorder. The second, with engagement of patients in treatment.

The primary aim of treatment is not only to challenge the patient’s belief that he/she is seriously ill. The aim of cognitive therapy is to offer the patient an alternative and hopefully more credible explanation of the problem. Therapy focuses on collecting evidence for an alternative psychological model which should present a conceptual shift away from the disease model held by the patient. In practise effective treatment involves a combination of directly challenging disease conviction and building an alternative model. In cases involving feared ‘mechanical’ failures of the body such as cardiac failures, breathing failures and so on, it is possible to devise experiments (like those in panic) to directly challenge belief by trying to make the failure happen. However, when misinterpretations concern diseases, such as cancer, that have a more general effect on the body, experiments mainly focus on collecting evidence for the cognitive model. More specifically, experiments cannot focus on making the catastrophe happen, but focus on demonstrating the effects of selective attention, rumination, bodily checking, etc.

Engagement in treatment

Engagement of health-anxious patients in treatment can be difficult and is hindered by negative patient expectations and attitudes towards health professionals. These attitudes may be based on past deteriorating doctor–patient relationships. In addition, problems can arise from a patient’s seemingly insatiable appetite for listing and describing signs and symptoms in minute detail, and a general preoccupation with physical symptoms at the expense of a concern with psychological factors. Attendance for cognitive therapy is not a guarantee that health-anxious patients are considering psychological explanations of their problem, and can merely reflect an attempt to show that the psychological approach does not work and, therefore, ‘there must be something seriously physically wrong’.

Given this sort of profile it is not surprising that many clinicians initially find some health-anxious patients difficult to engage in treatment. However, steps can be taken to diminish the problem. Engagement in treatment can be facilitated by using the following routine, or similar combination of these methods:

Example of the ‘no-lose’ engagement dialogue

FROM COGNITIVE MODEL TO CASE CONCEPTUALISATION

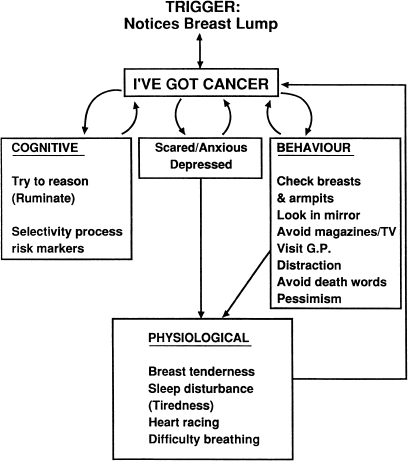

Although Figure 6.0 can be translated into an idiosyncratic case conceptualisation with little modification, simpler forms of the conceptualisation may be presented initially. When panic attacks are present, the first conceptualisation should take the form of the standard vicious circle model of panic (see Figure 5.1, p. 102). An initial formulation of panic offers a convenient way into the cognitive model, and panic attacks should be targeted for treatment before dealing with more chronic health concerns. Successful treatment of panic offers a means of socialising in the psychological model. Since the first stages of treatment focus on symptomatic relief (i.e. reduction in anxious health preoccupation) it is unnecessary to include predisposing beliefs in the conceptualisation at this stage. The central variables are negative misinterpretations and the cycles of maintaining factors as depicted in the idiosyncratic conceptualisation of Figure 6.1.

The construction of the conceptualisation is based on reviewing in detail recent health-anxious episodes, which may be exacerbations of general background health preoccupation. An illustrative excerpt of a therapeutic dialogue used in eliciting material for the conceptualisation in Figure 6.1 is given below. In this dialogue the therapist explores the cognitive, behavioural and affective factors associated with the maintenance of health preoccupation and disease conviction. In the example presented, note that there are a number of points which could have resulted in departures from the therapeutic goal of building a basic symptomatic conceptualisation. However, the therapist remained as focused as possible and flagged important themes for later exploration:

Figure 6.1 An idiosyncratic symptomatic health-anxiety conceptualisation

A significant feature of this patient’s problem was rumination as well as the usual checking and avoidance. An early component of the intervention was the exploration of beliefs concerning rumination to determine whether it had any appraised protective function. Anti-ruminative strategies were implemented early in treatment to demonstrate that reducing rumination about the cause of symptoms reduced health preoccupation.

SOCIALISATION

Treatment success is largely dependent on patients accepting a psychological explanation of their problem. This is most problematic in cases of strong physical disease conviction. Careful consideration must therefore be given to socialising health-anxious patients. The early use of behavioural experiments, in the first few sessions, can be a powerful aid to socialisation. Many of the procedures outlined in Chapter 5 can be adapted for use in health-anxiety treatment. If panic attacks are part of the health-anxiety scenario, it is helpful to begin by conceptualising and socialising with the panic model and treating discrete attacks before moving onto background health fears. In this way, the response of panics to treatment can be used as evidence for the conceptualisation.

Sample socialisation experiments

Treatment relies on building a credible alternative model of the presenting problem which is then adopted by the patient in preference to a physical illness model. On one level the whole treatment process can be viewed as extended and detailed socialisation. Five particular socialisation procedures are discussed below.

Tracking symptom patterns

By tracking the occurrence of symptoms such as dizziness, palpitations, and chest tightness, patterns in their occurrence may become apparent. The existence of symptom patterns can be used to challenge belief in disease-based explanations. For example, if symptoms such as dizziness occur most often in the mid-morning and during working days, this pattern is used to question the validity of a disease explanation: ‘If you have a serious disease why does it affect you most at certain times? Is there anything about these times that could account for your symptoms?’ A discussion of variables that could account for the patterns should be undertaken. Possible causes include: alcohol withdrawal, low blood sugar, or increased stress at a particular time of day. Symptoms can be tracked on modified DTRs or on blank activity schedules. For this strategy to be effective daily recording should be undertaken.

Reviewing the impact of reassurance

In cases where reassurance seeking has been evident the impact of verbal reassurance or medical test results on worry and symptoms should be reviewed. Typically, reassurance alleviates symptoms and worry and the effect can be used to reinforce a psychological explanation of the problem (i.e. ‘If reassurance relieves your symptoms what does that tell you about their cause?’). Questions like the following may be used in this context:

- What happens to your symptoms when the doctor tells you that they are not serious?

- If reassurance makes you feel better, would that work if you are seriously ill? Is reassurance a cure for . … (e.g. cancer, heart disease)?

- Would a serious illness respond to reassurance in this way?

- How do you think the reassurance works?

- What does that tell you about your problem?

The ‘intelligent disease’ metaphor

Both the identification of symptom patterns and a review of modulating influences such as reassurance effects can be used in conjunction with the intelligent disease metaphor. Here, the discovery of symptom patterns or response to reassurance is used to suggest that the illness or disease can ‘think for itself’ (e.g. How would a brain tumour know when it was being reassured?’). If symptom patterns are not evident from monitoring, or reassurance effects are absent, another strategy is a discussion of factors that exacerbate the patients symptom’s. If at first this is unclear, the presence of avoidance is often a marker for exacerbatory stimuli. For example, an individual may avoid watching medical television programmes or reading illness-relevant media material because this material increases symptoms. Such responses can be used as evidence for a psychological exploration of the patient’s problem (e.g. how would reading material about illness make symptoms of a brain tumour worse?)

Selective attention experiments

The use of self-focused selective-attention experiments was outlined in the previous chapter on panic. Similar experiments are effective socialisation strategies in the treatment of health anxiety. Prescriptive self-focusing strategies lead patients to notice normal bodily sensations (e.g. tightness of shoes on the feet, tingling in fingertips etc.) which they have normally not noticed. These procedures can also increase symptom intensity. The impact of these procedures can be discussed as analogous to the effect of bodily checking when this is prevalent. The primary supposition is that selective self-attention intensifies awareness of normal bodily signs and symptoms which are usually present, but new or intensified awareness can be confused as the occurrence of a new serious symptom. (Note: Re-attribution experiments also involve attentional manipulations such as attending to observable symptom-signs in other people. For example, a patient who misinterprets bald patches in beard growth as a sign of skin cancer could be asked to observe other peoples’ beard growth to determine whether this is an abnormal feature and likely to be a sign of danger.)

Education

The role of misinterpretation and the behavioural concomitants of misinterpretation in the maintenance of health anxiety should be presented in detail with reference to the patient’s case conceptualisation (e.g. Figure 6.1). Chapter 5 presents details on the use of education, and metaphor which can be adapted for use in the health-anxiety context.

REATTRIBUTION STRATEGIES

Cognitive restructuring in health anxiety gives equal emphasis to building an alternative understanding of the patient’s problem, and to challenging particular beliefs. In some instances a misinterpretation is not readily amenable to challenges. For example, if patients strongly believe that they have a serious illness but do not know what it is, or believe that the illness is latent (e.g. AIDS), and negative test results are unreliable, direct verbal and behavioural challenges of belief are likely to be unproductive. More generally, reattribution techniques that consist of providing an explanation for each of a patient’s various symptoms are also likely to be inefficient for long-term belief change. This type of approach tends to lapse into repeated reassurance giving, and the patient is likely to present with a weekly list of symptoms to be explained. Cognitive therapy for health anxiety depends on shifting the patient’s emphasis of appraisal away from focusing merely on symptoms to focusing on thoughts and behaviours associated with symptoms. When direct belief challenges can be used they are useful for an initial ‘loosening’ of the patient’s belief, which can then be followed by the collecting of evidence for an alternative model. Moreover, in cases where cardiac and respiratory concerns predominate, or generally where specific short-term catastrophic predictions can be made based on the patient’s belief, direct disconfirmation through experiment is easier to accomplish.

BEHAVIOURAL EXPERIMENTS

Testing patient predictions

Direct belief challenges can be used when there are specific predictions based on the patient’s illness conviction. When a patient believes, for example, that there is something seriously wrong with his/her heart, predictions can be made concerning the conditions under which the problem would manifest itself and lead to catastrophe. For example, vigorous exercise tasks could be employed to test this belief. As in the case of panic treatment, an analysis of the nature of avoidance and safety behaviours will usually suggest particular experiments which can be used to test predictions. These experiments will typically involve reversing avoidance and safety responses. An example of the implementation of a direct-challenge experiment in the case of a 34-year-old male health-anxious patient with a two-year history of belief in suffering from a serious muscle-wasting disease is presented below:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree