CHAPTER 28 Humeral Component

Humeral preparation and implantation of the humeral component of a reverse prosthesis are in some ways easier than with unconstrained arthroplasty. In many cases for which a reverse prosthesis is implanted, the rotator cuff is severely compromised or absent, which facilitates exposure of the proximal humerus. Additionally, because of the nonanatomic nature of the reverse prosthesis, preset resection guides are used in humeral preparation, thereby decreasing the importance of identification of the anatomic neck of the humerus, which is critical during implantation of an anatomically designed unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty.

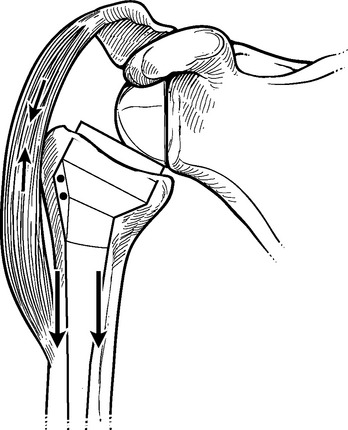

We implant all reverse-prosthesis humeral components with polymethylmethacrylate. The forces acting on the glenohumeral joint of a reverse prosthesis combined with the proximal humeral osteopenia that is often present in candidates for implantation of a reverse prosthesis may contribute to subsidence of uncemented reverse humeral components (Fig. 28-1). Subsidence of the humeral component may cause a critical loss of soft tissue tension and lead to glenohumeral dislocation. Consequently, most manufacturers recommend the use of cement fixation of the humeral component of reverse-design prostheses.

TECHNIQUE FOR INSERTION OF A REVERSE-PROSTHESIS HUMERAL COMPONENT

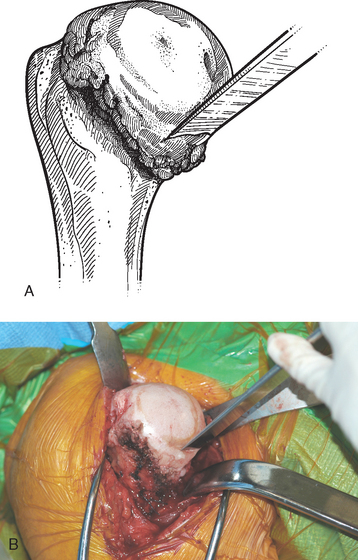

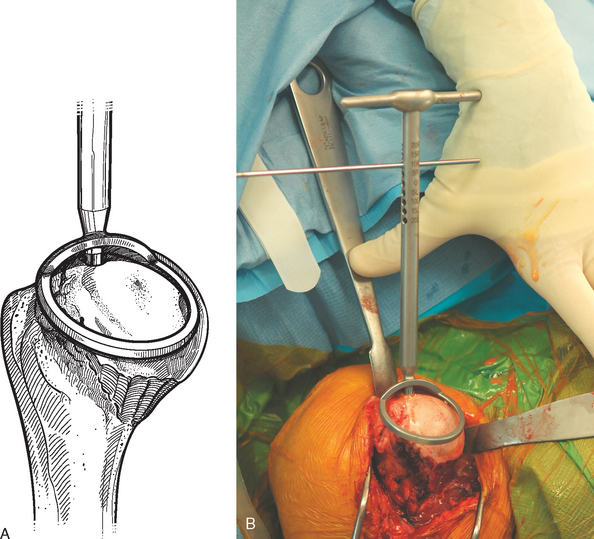

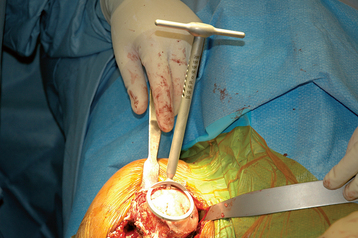

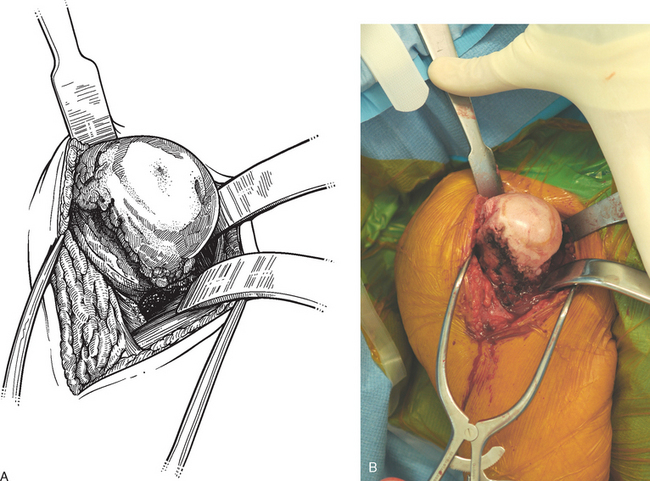

Once the inferior capsule is released from the neck of the glenoid as described in Chapter 27, humeral preparation begins. The humeral head retractor is removed, and the humeral head is dislocated by externally rotating and extending the arm. This maneuver is typically easier than in cases of unconstrained arthroplasty because the compromised rotator cuff offers little resistance to proximal humeral dislocation. A Hohmann retractor positioned superior to the coracoid process is moved to the margin of the humeral head, which is often “bald” (devoid of any discernible rotator cuff), and a modified Hohmann retractor is placed inferiorly and medially at the surgical neck of the humerus to complete the proximal humeral exposure (Fig. 28-2).

Figure 28-2 A and B, Completed exposure of the proximal humerus in preparation for insertion of a reverse prosthesis.

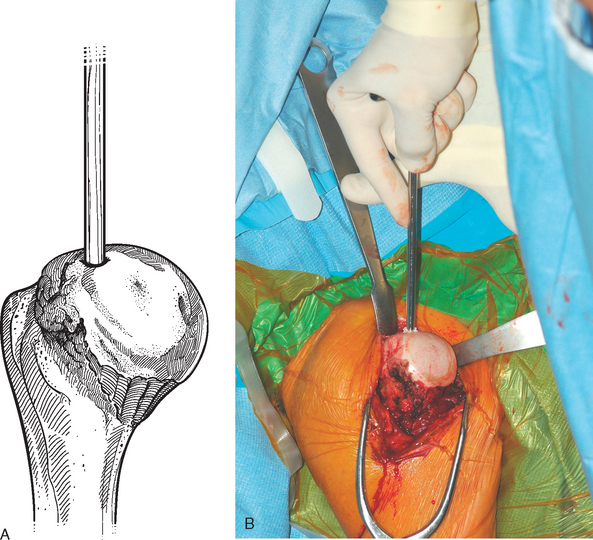

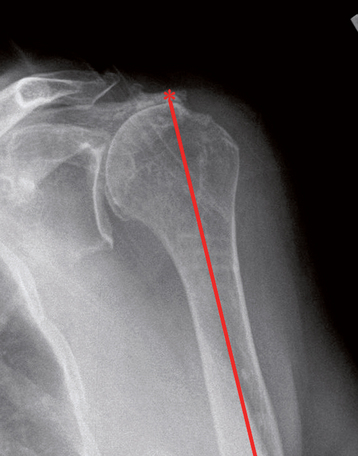

In most patients being treated with a reverse prosthesis, minimal if any peripheral humeral head osteophytes are present. In the uncommon situation in which large humeral osteophytes exist, they are removed with a half-inch osteotome and mallet, just as in cases of unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty (see Chapter 11). In contrast to cases of anatomic arthroplasty in which humeral osteophytes are removed to facilitate identification of the anatomic neck of the humerus to guide resection of the humeral head, osteophytes are removed in reverse-prosthesis procedures to avoid mechanical impingement between the osteophytes and the axillary border of the scapula (Fig. 28-3). A starter awl is used to open the humeral canal (Fig. 28-4). It is helpful to refer to preoperative radiographs to select the proper starting point for the awl, which should be in line with the humeral canal (Fig. 28-5). The humeral head can become deformed in patients with long-standing rotator cuff tears and can make identification of this starting point difficult. The humeral cutting guide, which sets resection at a 155-degree angle of inclination, is placed down the humeral canal (Fig. 28-6).

The system that we use allows selection of humeral cut version from neutral to 20 degrees of retroversion with the forearm used as a reference (Fig. 28-7). The advantage of resecting the humeral head in neutral is that less potential impingement may take place between the medial aspect of the humeral component and the lateral border of the scapula with internal rotation (Fig. 28-8). The disadvantage of resecting the humeral head in neutral is that in some cases the humeral cut may nearly miss the articular surface because the patient may normally have excessive humeral retroversion (Fig. 28-9). Conversely, the advantage of resecting the humeral head in 20 degrees of retroversion is that the humeral cut appears more nearly anatomic (Fig. 28-10). The disadvantage of resecting the humeral head in 20 degrees of retroversion is that more inferior impingement may take place with internal rotation (Fig. 28-11). As a compromise between these two extremes, we routinely select 10-degree retroversion with the alignment guide (Fig. 28-12). Resection of the humeral head is performed by resecting a small amount of bone by cutting just under the guide (Fig. 28-13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree