Human Metapneumovirus

Caroline Breese Hall

A player in the Mardi Gras of ills of years long past,

Though only recently it’s been unrobed

and now unmasked.

But just what role this respiratory reveler has to show

in its occult genomic soul we’ve yet to know.

— CBH

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) recently has appeared on the stage of human respiratory pathogens. Currently, its role may be described best as an understudy to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Thus far, it has been associated with primarily upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses, and sometimes with asymptomatic infections. Human metapneumovirus infections occur across the age span, with increased severity at each end: the young child and the older, compromised adult. Although hMPV was discovered only recently, serologic data indicate that it probably has been an occult contributor to the burden of respiratory ills for some time.

Van den Hoogen et al. initially discovered this new member of the Metapneumovirus genus, which previously had consisted of only avian pneumovirus. The virus was identified in a retrospective survey of specimens collected over the course of 20 years from patients with respiratory illness from whom 28 specimens were identified as containing hMPV. Within the next 2 years, reports of this same metapneumovirus in respiratory specimens came rapidly from Australia, North America, Europe, and Asian countries.

VIRUS CHARACTERIZATION AND LABORATORY CHARACTERISTICS

hMPV is the mammalian metapneumovirus first associated with disease and, like RSV and the parainfluenza viruses, belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family. Within this family are two subfamilies. The first is the Paramyxovirinae subfamily, which contains the parainfluenza viruses and the Hendra virus, among others. The second is the Pneumovirinae subfamily, which contains two genera: the pneumoviruses, to which RSV belongs, and the metapneumoviruses, to which this new hMPV has been assigned. Initial phylogenetic analysis indicated hMPV was related most closely to the turkey avian metapneumovirus, subtype C. Subsequent morphologic, antigenic, and genomic data have confirmed this relationship.

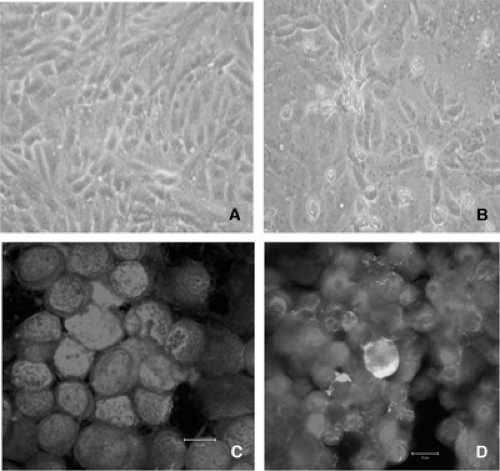

Similar to RSV and other paramyxoviruses, hMPV is an enveloped RNA virus with a nonsegmented, single-stranded, negative-sense genome. The envelope consists of a lipid bilayer that is derived from the plasma membrane of the host cells. Electron micrographs show pleomorphic, spherical, and filamentous particles of various sizes. The spherical particles have a mean diameter of approximately 200 nm, with a range of 150 to 600 nm. The filamentous particles have an average size of 282 × 62 nm (Fig. 190.1). Small, 13 to 17 mm spikes project from the envelope.

A sequencing of the genome has been accomplished and shows it to have a length of about 13.4 kB and eight open reading frames (ORFs) that are transcribed into eight distinct structural proteins. These proteins include the surface transmembrane glycoproteins, the fusion (F), attachment (G), and the small nonglycosolated hydrophobic (SH) proteins; two matrix proteins (M, M2); and three proteins that are associated with the nucleocapsid, the nucleocapsid protein (N), the phosphoprotein (P), and polymerase (L). The surface transmembrane glycoproteins have an arrangement within the virion similar to that of RSV.

hMPV Strains

Considerable strain variation exists for hMPV. Analyses of isolates from multiple countries suggest that at least two major distinct lineages (groups A and B). These two lineages have a nucleotide homology of 80% to 88%, whereas the homology is 93% to 100% within each of these two clusters. The amino acid homology is higher both between (93% to 97%) and within (97% to 100%) the two lineages. Two sublineages or subgroups also appear to exist in each of these two genetic lineages. Although the epidemiologic behavior of these strain groups is still incompletely understood, both appear to circulate simultaneously, with A strains generally predominating, but in those over 3 years of age as many B as A strains occur. However, the immunologic and clinical importance of strain variation remains to be determined.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The emerging epidemiologic picture of hMPV is based on a collage of mostly retrospective studies of relatively small numbers of patients. Nonetheless, the data accumulated thus far clearly show that hMPV is a ubiquitous agent with worldwide distribution that peaks in temperate climates during the colder autumn to spring months. In some countries, its seasonal pattern appears to be similar to that of RSV, although it generally is more variable; in countries with cooler climates, often its the peak of activity is less pronounced. The overall burden of respiratory illness engendered by hMPV compared to RSV and to other respiratory pathogens is still evolving, and direct comparisons are obfuscated by variations in the methods and populations analyzed.

The ubiquitous and early acquisition of hMPV has been shown by multiple serologic studies of various age groups. In Australia, specific antibody to hMPV was present in 90% of individuals by the time they reached the age of 5 years, and in 98% by 10 years of age. In the Netherlands, seroprevalence was similar, with 25% of subjects positive at 6 to 12 months of age, and almost all by age 5 years. Clinical disease, however, is detected in a much smaller proportion of children, suggesting that many infections are very mild or asymptomatic.

The proportion of acute respiratory illnesses caused by hMPV generally has been estimated in most recent reports as 1% to 3% in the general population of all ages, 5% to 9% in young children, and 2% to 7% in adults. The rates have been highly variable in different populations, but usually highest in those younger than 2 years, over 65 years, with underlying conditions, and those hospitalized or in long-term care facilities. Of banked specimens from individuals with respiratory disease submitted to diagnostic laboratories, hMPV has been identified in approximately 4% to 16%. hMPV has been detected in 1% to 4% of specimens from asymptomatic individuals. As with those infections caused by other respiratory pathogens of young children, those from hMPV resulting in hospitalization occur 1.2 to 2.3 times more frequently in boys.

In a recent study (Williams et al.), specimens that had been collected over 25 years from healthy children younger than 5 years of age attending a vaccine clinic were analyzed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the presence of hMPV. Nasal wash samples were examined from 687 visits for lower respiratory illnesses among 463 children, 57% of whom were 24 months of age or younger. Viruses other than hMPV were identified in 279 (41%), with RSV accounting for 103 of the 279 (37%) virus positive samples. In 248 of the virus-negative samples, hMPV was identified in 49 (20%), which, if extrapolated to the total cohort of children with lower respiratory tract disease would indicate that 12% of lower respiratory tract illnesses were caused by hMPV, similar to the 15% from RSV in this defined group of young children.

Two prospective population-based studies have examined the burden of lower respiratory disease caused by hMPV in hospitalized children, one in the United States (Mullins et al.) and one in Hong Kong (Peiris et al.). HMPV was identified by RT-PCR in 3.9% of the 668 samples obtained from children younger than 5 years of age hospitalized for acute respiratory illness in Rochester, New York and Nashville, Tennessee. In comparison, RSV was identified in 18.7%, parainfluenza viruses 1 to 3 in 6.7%, and influenza in 3.4%. The estimated hospitalization rates per 100,000 persons for hMPV were 114 cases for children younger than 12 months of age, 131 cases for 1- to 2-year-olds, and 10 cases for children 2 to 5 years of age.

In a similar population of 587 children 3 to 72 months of age hospitalized with acute respiratory illness in Hong Kong, the rate of hMPV-associated admissions was similar at 5.5%, and the annual rate of hMPV hospitalizations was estimated as 442 hospital admissions per 1,000 children younger than 6 years of age.

Although firm estimates of hMPV’s role in causing respiratory illness are difficult to obtain from recent studies of varying populations and laboratory methods, clearly hMPV appears to be a major actor in the burden of acute respiratory illness borne by the young child and an epidemiologic mime of RSV.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree