The proximal femur has historically been the site of choice for the realignment of the hip. Intertrochanteric osteotomy (ITO) is the most established hip-joint–preserving procedure. In 1826, John Rhea Barton of Philadelphia performed the first osteotomy on a patient with posttraumatic ankylosis and successfully produced a painless pseudarthrosis. He and Kirmission (1894) were the first to describe proximal femoral osteotomy.

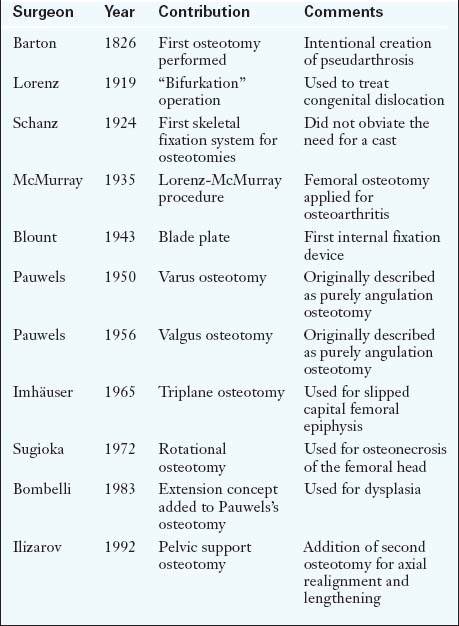

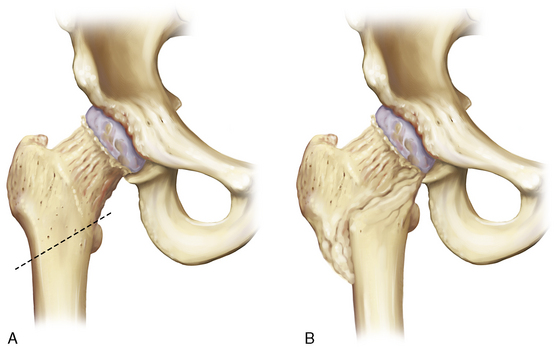

Early on, adult sequelae of developmental hip dysplasia were the most common indications for an ITO (Table 1-1). Early reports of realignment osteotomies of the proximal femur involved either displacement or angulation. Hip dysplasia was the first application of this procedure, although now it rarely constitutes an indication, at least for an isolated femoral osteotomy. Adolf Lorenz (1919) described his “bifurkation” operation, and Schanz (1922)—among others—also introduced a variation of Kirmission’s procedure, mainly for unreduced congenital dislocation of the hip. Both of these procedures were of the pelvic support osteotomy type. Lorenz outlined ten indications for his procedure, with advanced osteoarthritis being the eighth. In his report in 1935, McMurray from Liverpool adopted Lorenz’s procedure, and he is the one who popularized proximal femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis. The so-called Lorenz-McMurray procedure was described—but not performed in reality—as an excessively oblique cut (Figure 1-1). Although it was originally described as a purely displacement osteotomy, it did secondarily employ valgus angulation. McMurray believed that the primary mechanism of pain relief was the bypass of the proximal femur during the transmission of loads from the pelvis to the distal fragment. Displacement osteotomies were widely used in England, with Malkin (earlier) and Nissen (later) being their most eminent proponents.

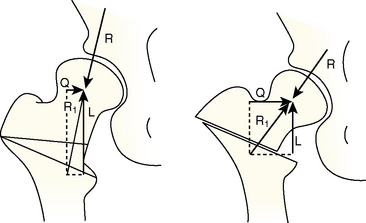

The prototype angulation osteotomy was described in 1950 by Pauwels, who designed a varus osteotomy above the lesser trochanter without displacement; he initially applied this procedure to young adults with hip dysplasia associated with the subluxation of a spherical femoral head. In 1956, he introduced valgus osteotomy for those hips that obtained improved congruity in adduction and for nonunited fractures of the femoral neck. About 10 years after the original description by Pauwels, the procedure came to include the medial displacement of the distal fragment (Figure 1-2).

Early on, Pauwels realized the importance of medial displacement for relieving tension from the iliopsoas and adductor muscles. He was also aware of the necessity of maintaining the overall alignment of the hip. Pauwels’s contribution to the current understanding of hip biomechanics cannot be overemphasized. He was the first to explore the concept of reducing muscle moment arms by changing the orientation of the proximal femur, and he stated that a horizontal sourcil denotes biomechanical equilibrium.

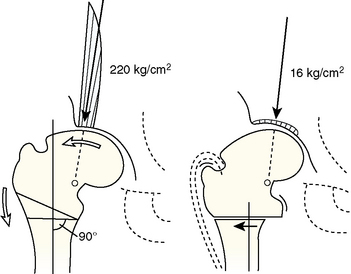

His ideas were taken a step further by Bombelli, who reached the same conclusions through a modified consideration of the primary hip forces. In addition to his theoretical model, Bombelli also modified Pauwels’s valgus osteotomy by adding extension in the sagittal plane for improved femoral head coverage in dysplasia, for the relief of flexion contracture, and for the correction of hyperlordosis. He also suggested that, in the case of a valgus osteotomy, one should exploit the inferomedial capital drop osteophyte (Figure 1-3) and put the lateral capsule to enough stretch to stimulate the formation of the roof osteophyte, both for the purpose of increasing the weight-bearing area of the joint.

The skeletal fixation of femoral osteotomies was first described by Schanz in 1924, who devised a simple external fixation system composed of one screw on either fragment. Because of the obvious biomechanical instability of his device, Schanz’s patients still relied on a plaster-of-Paris spica cast. Blount of Milwaukee popularized the use of internal fixation in 1943 with the use of the “V” blade plate. Interestingly, McMurray used two casts for fixation, whereas Pauwels used a short intramedullary nail until the application of the cast. In 1955, Müller introduced fixed-angle blade plates; the 95- and 110-degree versions are still the ones that are most commonly used for the fixation of varus and valgus ITOs, respectively, although a dynamic hip screw is now also used. The advantage of today’s blade plates is inherent in their design, which allows for the appropriate translation of the distal fragment. Pauwels, Müller, and Bombelli are the surgeons who set forth the principles of femoral osteotomy.

Recent refinements of the varus osteotomy have focused on the amelioration of abductor weakness, which is the major drawback of this procedure. Müller (1984) recommended a simultaneous distal transfer of the greater trochanter, and Nishio (1984) described a dome osteotomy of the femoral neck, which leads to distalization and lateralization of the greater trochanter. The Morscher osteotomy (1999) combines the distal transfer of the greater trochanter and the lengthening of the femoral neck without reorienting the femoral head.

Salvage femoral osteotomies include hip joint resection, Colonna’s trochanteric reconstruction (1960), and pelvic support osteotomies. These osteotomies were originally described by Lorenz and Schanz, and they were popularized by Milch and Bachelor. However, they fell into disfavor because of the significant shortening and valgus malalignment that they produced. Ilizarov (1992) modified the procedure by adding extension in the sagittal plane and a second more distal femoral osteotomy for lengthening and realignment. The best indication for this operation today is the sequela of neonatal hip sepsis in the older child or adolescent.

With the development of so many different types of osteotomies, it is easy to forget the principle stated in 1964 by Blount in his article published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery: “… all of them are in fact variations of one procedure which must be modified according to the clinical and roentgenographic findings.” Depending on the underlying pathology, a number of combined corrections in the frontal and sagittal planes may be implemented and may even be coupled with derotation.

Thus, it is imperative that the surgeon be familiar with the basic tenets of deformity correction. When the osteotomy is at a level that is different from the center of rotation or angulation, the secondary translation of the fragments at the level of the osteotomy will occur (this is the second osteotomy rule, according to Paley and colleagues). When one considers the proximal femur, this corresponds with the medial or lateral displacement of the shaft in the case of a varus or valgus osteotomy, respectively (i.e., displacement–angulation osteotomy). This ensures the optimal alignment of the entire lower extremity, provided that no other deformity is present. Despite the clinical and geometric documentation of the beneficial effect of femoral translation, some surgeons do not advocate this principle, because there are concerns about the technical feasibility of a future total hip replacement.