Chapter 2. History and clinical examination

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• Take an appropriate history.

• Perform a competent general clinical examination of all joints.

• Understand and use the correct orthopaedic terminology.

• Competently perform the common examinations of large joints.

If you are uncertain about the meaning of a word, look it up in the Glossary on p. 467.

History

In most branches of medicine there is seldom any argument about the correct management once the diagnosis has been established. Orthopaedic surgery is different: the diagnosis is easy but the choice of management is difficult. The appropriate treatment varies from one patient to the next and is determined by age, sex, occupation and home circumstances, all of which must be established while the history is taken. The patient’s attitude is also important and it is helpful to consider the following points while taking the history.

General aspects of a consultation

1. Why has the patient come?

2. How well motivated is the patient?

3. Does the patient have a reason (litigation, for example) not to hope for recovery?

4. Does the patient have realistic expectations of treatment?

5. Has the patient really understood what you have said?

The patient

Reason for consultation

Most patients will be looking for the relief of pain or deformity but many seek only an explanation of their condition and its likely progress. A patient with sudden pain in one joint may be worried because a relative had severe arthritis that began with pain in just one joint and the patient fears that she, too, is destined for a wheelchair. Other patients fear that their pain is the first sign of widespread cancer, particularly if a relative died with bone metastases; and parents’ worries about the shape of their children’s feet can be fuelled by concerned grandparents, friends or health visitors.

These patients need nothing more than a sympathetic ear, firm and authoritative reassurance, and a careful explanation of the condition and its prognosis. To treat the symptoms energetically will only increase the patient’s anxiety.

Motivation

Motivation is very important. Many orthopaedic operations demand hard work and complete cooperation from the patient in the postoperative period. If the patient gives the impression of being unable or unwilling to take an active part in the rehabilitation process, there is unlikely to be a good result from operation, however well it is done. To detect such people before operation is difficult, but only too easy after operation.

Litigation

When symptoms are the result of a road traffic accident or an injury at work, the patient may be involved in legal action to obtain compensation. Although the great majority of patients give a perfectly honest and straightforward account of their symptoms, they cannot help becoming a little introspective if they think that compensation is related directly to the severity of symptoms. Most people involved in litigation will say so, but if this is not mentioned and patients begin the history with the exact date when the symptoms began, they should be asked specifically about impending litigation. A clear and careful record of the symptoms is essential in these patients and may be a little more difficult than usual to obtain.

Patients’ expectations

Sensible patients understand that no operation is painless and that all leave a permanent scar, but some expect the impossible. Athletes cannot accept that declining performance is due to age, and patients with gross osteoarthritis expect a perfect cure. If treatment is offered to patients with unrealistic expectations they are bound to be disappointed, and are sometimes even vengeful. It is as well to recognize such people before any definitive treatment is suggested.

Does the patient understand?

No matter how thorough the explanation of the condition or proposed operation, it is unlikely that the patient will remember everything that has been said. Some understand more than others but a few do not remember a word. Because close cooperation between patient and doctor is particularly important in orthopaedic surgery, special attention must be given to ensuring that the patient understands as clearly as possible exactly what the treatment involves.

Specific questions

Apart from general impressions of the patient’s attitude, specific questions must be asked, both to establish the diagnosis and to select management. Social and occupational histories are vital because the impact of symptoms on lifestyle varies from one patient to the next. It is essential to have detailed information about the patient’s occupation and home circumstances before any treatment is suggested.

Specific questions

1. Symptoms. Record them as precisely as possible.

2. Occupation. Find out the exact nature of the patient’s work.

3. Impact of treatment. How will it affect the patient’s work, life, leisure, etc.?

4. Home circumstances. Are the stairs at home easy to climb? How far away are the shops? Is there any help in the house?

Symptoms

Pain, deformity, swelling and loss of movement in a joint are the commonest complaints in an orthopaedic clinic. The duration, manner of onset (sudden or gradual) and variability of the symptoms must all be established. If there is a joint swelling, is it related to use of the limb? If so, does it begin during the activity, or the next day? These are the same straightforward questions needed in any clinical history except that, when asking about pain, special attention should be paid to referred pain, a classic pitfall for the unwary. The commonest example is pain in the knee caused by disease at the hip.

Occupation

Find out not only the name of the patient’s job but also exactly what it involves. One driver may spend the entire day sitting behind the steering wheel but another will have to load and unload the vehicle, which entails a great deal of heavy physical work. A lathe operator who stands for most of the day could not work with a painful foot but could manage with a stiff knee, while a motor mechanic could tolerate a painful foot but a stiff knee would make it impossible to work in tight corners or under vehicles. The loss of the terminal phalanx of the ring finger would be of little consequence to a labourer, but disastrous to a musician.

Impact of treatment

Treatment always disturbs the patient’s life, sometimes seriously. To suggest an operation that would make a self-employed tradesman unable to work for 2 or 3 months needs careful thought. Timing is also important: to be rendered unfit during the harvest could bring financial ruin to a single-handed arable farmer for whom the quietest period of the year is at Christmas; on the other hand, shopkeepers need to be at their fittest during the Christmas period and, except in a tourist centre, would probably choose August for operation.

Home circumstances

Knowledge of the home circumstances is vital when dealing with the elderly. Problems are inevitable if the patient cannot climb stairs and the only lavatory is on the top floor. If the patient cannot walk out of the house, who will do the shopping?

These mundane details have no bearing on the diagnosis or the operations that are technically possible but they have everything to do with selecting the right treatment for the individual patient.

Clinical examination

Approaching the patient

Every clinical examination should be conducted carefully, confidently and without hurting the patient needlessly, which is difficult when muscles are tight or rigid. The patient must be encouraged to relax. If an injured, perhaps broken limb is to be put into the hands of a stranger, the patient must have complete confidence in the person carrying out the examination.

The simplest and best way of obtaining the patient’s full confidence is to conduct the examination calmly, methodically and without fumbling. The patient can easily tell (as can an examiner) if a doctor or student is doing something for the first time. Only practice brings confidence.

Routine of examination

The established routine for clinical examination in orthopaedic surgery is as follows:

Routine for clinical examination

Routine for clinical examination

| Inspection Palpation | Listen to what the patient tells you. Look at the area. Feel gently for swelling, painful areas, temperature changes and tenderness. Measure limb length and girth. |

| Movement | Move the limb to assess the range of motion. Active movement is observed first, then passive. |

| Stressing | Strain the ligaments to look for abnormal movements. Radiographs are useful but do not replace any part of the clinical examination. |

| Note: Examine painful areas last! | |

Take heed of that final note – in practice there is much to be said for leaving the most painful manoeuvre until last, even if this means breaking the routine of examination. In particular, do not start the examination by leaping to the most painful area, prodding it and making the patient jump; to begin the examination thus usually marks the end of cooperation. There is also much to be said for examining any available radiographs before examining the patient, especially if there is a fracture.

Children, particularly between the ages of 1 and 3 years, must be approached with caution. It is virtually impossible to derive any useful information by examining a screaming and struggling child, but there are several ways to overcome this problem.

First, do not overwhelm the child with attention as soon as he or she enters the consulting room. A quiet talk with the parents will give the child time to appraise the doctor and decide that there is no threat.

Second, children do not like to be laid flat on an examination couch; if any part of the examination can be conducted with the child sitting on the mother’s knee, so much the better.

Third, children do not like strangers examining their bodies but they rather enjoy strangers admiring their clothes, and this vanity can be exploited. To look carefully at a child’s shoes, for example, gives the opportunity to put the hip, knee and ankle through a full range of movement, assess limb length and muscle tone and look for deformities.

Finally, if a child does have to be stripped and laid flat on the couch, leave that until last.

Inspection

Much information can be gained simply from looking at the patient as a whole rather than concentrating on details; a slow, careful inspection of the painful area can give more information than palpation and manipulation combined. The area must be fully exposed and properly prepared: a shoulder cannot be examined through a shirt or a knee through trousers.

When examining a limb, always compare the two and ask yourself the following questions:

1. Is one limb straighter or shorter than the other?

2. Are the joints swollen?

3. Is there muscle wasting?

4. Are there any scars and, if so, are they surgical or traumatic?

Examining a limb

• Deformity?

• Shortening?

• Swelling?

• Wasting?

• Scars?

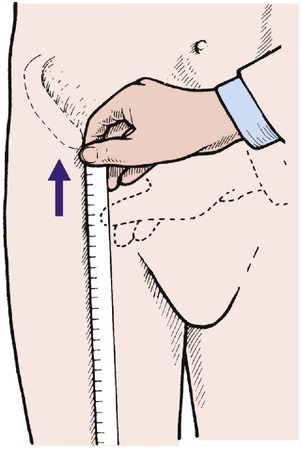

Measurement is part of inspection. To measure the distance between bony points, choose fixed points that are easily recognizable, such as the medial malleolus or anterior superior iliac spine, rather than variable points, such as the umbilicus or the centre of the patella. When applying the end of the tape, run the finger past the bony point and bring the tape back up to it (Fig. 2.1). This reduces the error caused by overlying soft tissue.

|

| Fig. 2.1 Measuring the distance from a bony point. Move the hand just past the bony point and then back up to it. |

When measuring limb girth, be sure that the measurements are reproducible and that the point of measurement is recorded, e.g. the narrowest part of the ankle, the widest part of the calf, or the thigh at a measured distance above the tibial tubercle.

Palpation

There is a strange temptation to start palpation by poking the painful area, but this should always be deferred until last. A hand laid gently on the affected area will detect abnormal warmth, and gentle pressure will identify soft tissue swelling or a joint effusion.

Firmer pressure will locate swellings and tender areas, and show whether the patient is apprehensive when the area is touched. Apprehension is significant, particularly if the joint is unstable, as in patients with recurrent dislocation of the patella.

Sensibility. Sensibility is examined in the usual way, but with a special effort to try to relate the pattern of abnormal sensibility to anatomical structures, such as the distribution of a cutaneous nerve or dermatome (see Ch. 3).

Movement

Always compare the range of movement with the opposite limb. This is essential because there is a wide variation in the ‘normal’ range of movement.

The quality of movement is also important. Is the movement free, or stiff? Smooth or noisy? Does the joint feel loose and unstable? Is it sound? These are subjective assessments and judgement only comes with experience.

Range of movement. The movement in a joint is always measured from 0°, every joint being at 0° when the body is in the anatomical position (Fig. 2.2). This convention is now almost universal but there are still a few who refer to the straight joint as being at 180° instead of 0°, and this causes untold confusion.

|

| Fig. 2.2 The anatomical position with the palms facing forwards and thumbs outwards. |

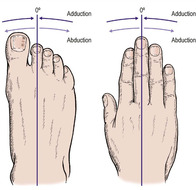

In most joints, flexion/extension are in the sagittal plane and abduction/adduction, which represent movements away from and towards the midline of the body, in the coronal plane. Abduction and adduction of the toes and fingers are measured from the second toe and the middle finger (Fig. 2.3).

|

| Fig. 2.3 Abduction and adduction of the digits. The toes are adducted to the second toe and the fingers to the middle finger. |

Rotation occurs about the long axis of a structure and circumduction is movement of a limb in a circular direction.

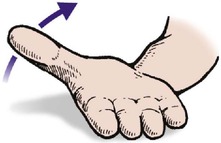

The only slight exceptions to these rules are for the thumb, the movements of which are in a plane facing about 30° forward from the coronal plane. Flexion and extension, abduction and adduction of the thumb are all measured relative to this plane (Fig. 2.4).

|

| Fig. 2.4 Movement of the thumb in the direction of the arrow is adduction. |

Stressing, straining and strength

Ligaments. Ligamentous instability, which is difficult to assess, is detected by stressing the ligaments and looking for excess movement.

Muscle power. Muscle weakness must be looked for and recorded. The muscle power is graded according to the MRC (Medical Research Council) scale, which recognizes six grades of muscle power (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 – do not forget 0):

This may sound complicated but it can be simplified by remembering that 0 is complete absence of power and 5 is normal, and the difference between 2 and 3 is the ability to move the limb against gravity.

Examination of individual areas

Every area must be examined carefully according to a routine but the important parts of the examination vary from area to area. This section sets out the things which should be looked for particularly carefully but this does not mean that the rest of the examination is unnecessary.

Cervical spine

Inspection

Although deformity of the cervical spine is unusual, always look at the head and neck as a whole before palpating or assessing movement. Patients with cervical spondylosis, for example, may have a ‘poke’ neck, and deformities of the cervical spine are seen in the Klippel–Feil syndrome (p. 447) and a few other conditions. Check also that the patient can support the head without difficulty – instability of the cervical spine can be easily missed in a recumbent patient.

Palpation

Midline tenderness over the supraspinous ligament is found after injuries to the neck, such as a sprain or whiplash injury. A defect is sometimes felt in the supraspinous ligament following a major spinal injury, and is a serious finding (p. 152). Tenderness and spasm of the paraspinal muscles extending down to the trapezius are found in cervical spondylosis.

Movement

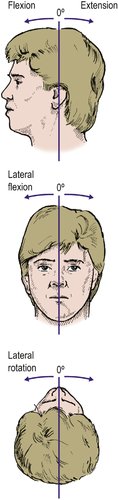

Movement of the neck cannot be assessed in degrees like a simple synovial joint; it is expressed as a percentage or fraction of the usual range, e.g. two-thirds normal, half normal, 50% normal (Fig. 2.5). The patient can be examined sitting down, to eliminate compensatory movements in the thoracic and lumbar spine. The following movements are recorded:

• Flexion – ‘look downwards’.

• Extension – ‘look upwards’.

• Lateral rotation – ‘look over your shoulder’.

• Lateral flexion – ‘lean your head sideways’.

|

| Fig. 2.5 Movements of the cervical spine. |

The combined range of flexion and extension is about 110°. Flexion and extension are best seen from beside the patient, and the lateral movements from behind.

Stressing the cervical spine is not helpful.

Thoracic spine

Inspection

Deformities of the thoracic spine are important.

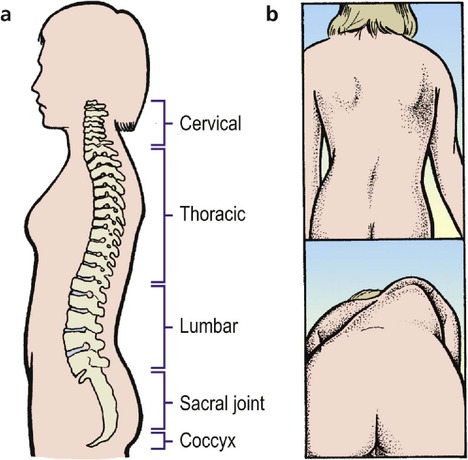

Scoliosis usually develops during adolescence but also occurs in early childhood. The rib ‘hump’ is demonstrated by standing behind the patient and asking them to bend forward with the hands held together (Fig. 2.6 and Fig. 2.7).

|

| Fig. 2.6 The spine: (a) the successive lordosis and kyphosis of the cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions; (b) scoliosis can be seen with the patient standing but is more marked when the patient leans forward. |

|

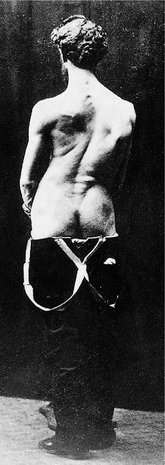

| Fig. 2.7 Thoracic scoliosis. From Sayre LA (1877) Spinal Disease and Spinal Curvature. By kind permission of the Wellcome Institute Library, London. |

Kyphosis is best seen from the side (Fig. 2.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree