Chapter 7 Headache in Whiplash

A Comprehensive Overview

Acquiring data from emergency department records is also problematic. Post-whiplash headache may not appear in the first 24 or 48 hours, and even if it does, it may not be the chief complaint and may not be recorded clearly or prominently. Furthermore, not everyone involved in a car crash will present to the emergency department. Prevalence data of whiplash-associated headache are thus estimates and have been reported as varying from 32% to 80%.1 Whereas costs of whiplash have been estimated at $4.5 billion annually in the United States, the costs of whiplash-associated headache are unknown.

Taking a Headache History

Studies of doctors and patients have found that the best way to elicit history is to ask open-ended questions and allow the patient to tell their story. The American Migraine Communication Study, in particular, found this was especially important in taking a headache history.2 Ask patients to describe when their headaches began and how their headaches feel. Allow them to speak, uninterrupted, until they are finished. You will find that with most patients, this takes only about 2 minutes or less. Then you may begin to ask more specific questions to fill in the gaps of what you need to know.

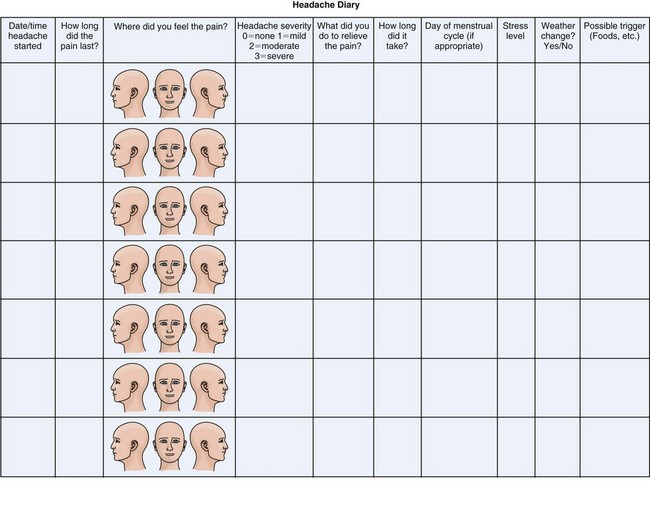

Frequency of headache may at first be daily. However, as recovery progresses, the headache disorder usually becomes intermittent, and it is important to see the frequency and duration of headache attacks. Headache diaries can be useful in this regard (Figure 7-1).

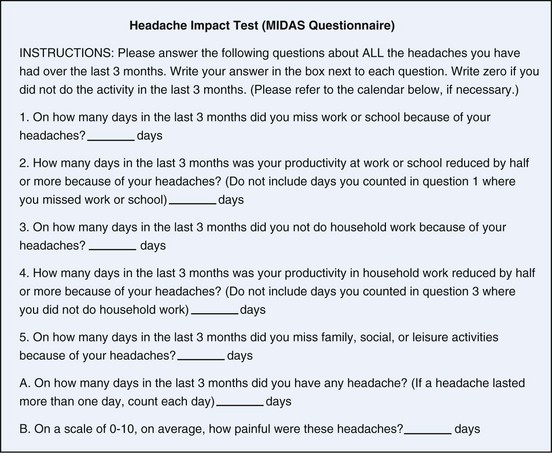

Many patients do not understand the term “quality of pain”; just ask them “What does the pain feel like?” Sometimes, it may be necessary to prompt with adjectives, such as squeezing, dull, sharp, or throbbing, but it is best to avoid this if possible, and allow patients to express it in their own terms. Severity of pain is often expressed in descriptive terms rather than a numeric scale. One person’s “3” may be another person’s “6.” A standard practice in headache medicine is to grade headache pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Others prefer a 0-10 pain scale such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Both scales are useful in the ongoing evaluation of headache to monitor progress of individual patients. Pain scales are subjective and not reliably reproducible between patients. If more objective measures are desired, it should be realized that current technology does not support objective measurement of the experience of pain. The best that can be done is the standardization of subjective reports, and for that, the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) can be used.3 Although the HIT-6 is a measure based on subjective reporting by the patient, it is a standardized method that yields a numeric value and thus means the same thing to everyone. The Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS), devised for measuring disability related to migraine headache, can also be adapted for other headache types and provides a quantifiable scale as well4 (Figure 7-2).

Visual disturbances also occur in association with headache disorders. Some visual disturbances are intrinsic to the headache itself, which usually occurs in migraine headaches. Existing migraine headaches may be exacerbated by a whiplash injury and can certainly be exacerbated by head injury.5 However, visual blurring, double vision, or changes in visual processing can occur as a consequence of mild head trauma or whiplash in those who have never experienced migraine.6,7

And, finally, at the conclusion of the patient encounter, it is useful to ask if the patient has additional issues or questions. Research done at UCLA in primary care indicates that it is more effective to ask, “Is there something else you want to address in the visit today?” than to ask, “Is there anything else you want to address in the visit today?” Surprisingly, this single word change brought out answers in an additional 40% of patients.8

Types of Headache That Might Be Encountered

Posttraumatic Headaches

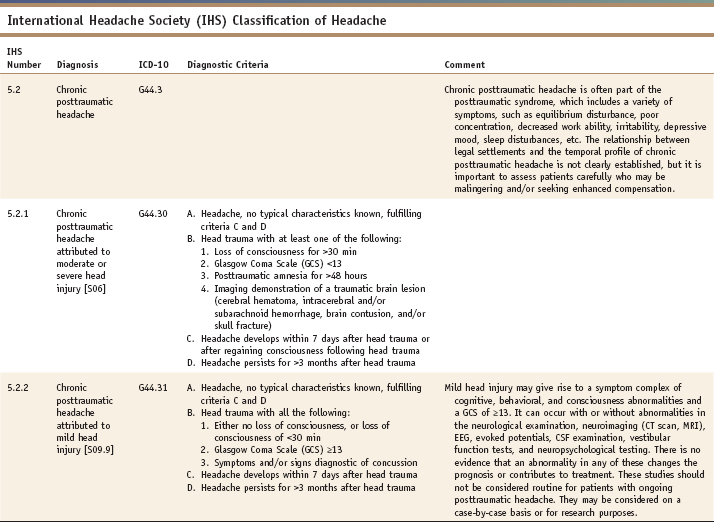

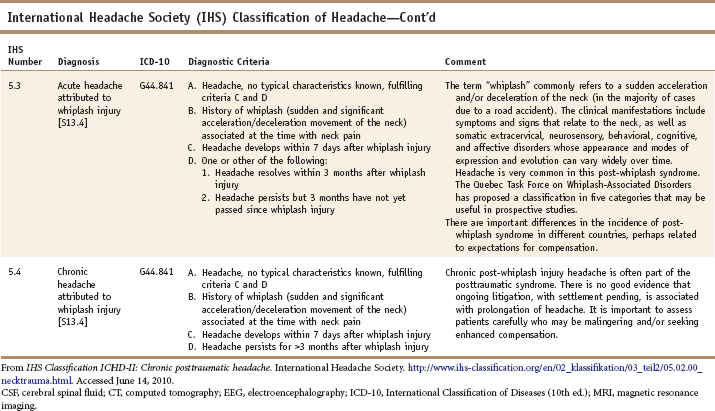

The posttraumatic headache is defined as a headache following head trauma. There are a variety of grading systems for head injury. In terms of classifying posttraumatic headache, the International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition (ICHD-2) of the International Headache Society (IHS) has divided posttraumatic headaches into acute and chronic and into mild and moderate-severe (Table 7-1). In this scheme, moderate or severe head injury requires loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma score of less than 13, or posttraumatic amnesia for more than 48 hours. Mild head injury in the ICHD-2 requires all these: no loss of consciousness or loss of consciousness less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow coma score ≥13, and symptoms or signs diagnostic of concussion.9

Posttraumatic headaches occur in a high proportion of head-injured individuals. Motor vehicle collisions are the most common cause of head injuries, constituting 42%. Earlier estimates indicated that between 30% and 50% of those who sustained mild head injury would experience headache lasting 2 months or more; more recent data suggest acute posttraumatic headache affects up to 80%.10,11 Mild head injury is associated with an increased risk of chronic posttraumatic headache.12 Paradoxically, the severity of head injury is inversely proportional to the severity of posttraumatic headache.13 Posttraumatic headache results in more disability than the primary headaches do (migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, and others).14

There is no usual headache type that characterizes posttraumatic headache. The pain may be constant or intermittent, pulsating or non-throbbing, sharp or dull. In some patients, there may be more than one type of headache pain reported. Photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting are fairly common in posttraumatic headache. The presence of double vision, anosmia, or other neurological abnormalities indicates a higher likelihood of chronic posttraumatic headache. Anosmia, memory loss, dizziness, irritability, depression, anxiety, and personality change occur in 20% to 25% of those with chronic posttraumatic headache.11

The exact pathogenic mechanisms of posttraumatic headache remain unclear. Historically, “chronic” posttraumatic headache had to last more than 2 months. More recently, the IHS ICHD-2 somewhat arbitrarily declared 3 months as the cut-off for chronic posttraumatic headaches.9 Approximately 20% of posttraumatic headaches will last more than 1 year, and a substantial number of these may become permanently chronic headache.15

Whiplash-Associated Headache

Headache occurs frequently as a consequence of whiplash and may affect up to 80% of individuals in the first 4 weeks. Continued symptoms are more likely if there are abnormal neurological findings, degenerative joint disease seen on x-rays, or a prior headache history.11 Headache is often more severe if the occupant of the vehicle is unprepared for the collision. Headache and neurological symptoms are more likely to occur in rear-end collisions.16

There is no specific headache type that characterizes the whiplash-associated headache. The headache symptoms may mimic either tension-type headache or migraine headache and, in one study, were reported in equal proportions. In another study, however, headaches reported were either generalized, dull, aching pain, a mixture of aching and tightness, or more typical tension-type headaches. Only 3% described headache pain typical of migraine. Unlike posttraumatic headache, continuous headache was short-lived, and lasted only 3 weeks in 85% of cases.17

A 2001 study found a fairly even distribution of headache types following whiplash, with 37% reporting tension-type headache, 27% migraine headache symptoms, 18% cervicogenic headache by IHS criteria, and 18% not fulfilling specific headache criteria. Most importantly, however, 93% of patients reported neck pain in conjunction with headache pain.18

Cervicogenic Headache: A Matter of Terminology

There have been diagnostic criteria established by the IHS, as well as by the Cervicogenic Headache International Study Group (CHISG).9,19 The difficulty at present is that it has been determined that upper cervical and posterior head pain is common in primary headache disorders such as migraine, tension-type headache, and even trigeminal autonomic cephalgias. The mere existence of neck pain is not sufficient for a diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. Moreover, existing criteria do not adequately address biomechanical concerns.

The CHISG diagnostic criteria have, since 1998, been somewhat muddied by various reports of migraine symptom patterns. The criterion requiring unilateral neck pain has been eroded by several reports of migraine presenting with neck pain. There has also been a recent study describing reduced cervical range of motion in women with migraine, casting some lack of clarity on that criterion for cervicogenic headache.20 The IHS criteria have, in the revised version, been simplified to the point of a danger of lack of specificity. In the CHISG criteria, the underlying principle is that the diagnosis is not proved without invasive diagnostic anesthetic nerve blockade of C2, the “third occipital nerve,” or other suspected cervical structures, including facets.

Pre-existing Headache Syndromes Exacerbated by Whiplash

A pre-existing headache syndrome is prone to worsening when subjected to a whiplash injury. The argument has been made, in fact, that whiplash headache is solely due to a transitory worsening of a pre-existing primary headache.21 This conclusion was based on the logic that both the collision group and the matched controls had the same long-term prognosis (at 1 year), and that therefore the headaches were primary headaches, with worsening most likely induced by the stress of the accident situation. Given that this study was conducted in Lithuania by the same investigators who did the original Lithuanian study, it would be reasonable to conclude that there might be some bias present.22

A retrospective records review of 2,771 headache patients, looking for correlation with trauma, found a trauma history in 1.3% of migraine patients, 1.5% of tension-type headaches, and 15% of cervicogenic/neck-associated headaches. The majority of the traumatic incidents were believed to include a whiplash action. Some of the headaches occurred remote to the trauma history. This data set suggests that worsening of migraine, if present, is not likely to be long-lasting on the basis of whiplash injury.23 Anecdotally, many headache experts will state that pre-existing headache disorders will be exacerbated by whiplash injuries. Unfortunately, this population is often excluded from study populations, and thus, many questions remain.

Temporomandibular Dysfunction

TMD occurs more frequently in women, with a 4 to 1 ratio reported.24 In the setting of trauma, there has often been a tendency to attribute TMD primarily to personality factors rather than to sequelae of trauma, similar to the tendency to dismiss chronic TMD in nontrauma patients as a function of personality factors or psychiatric disorders.

Clearly, not everyone with TMD is depressed. There is a study that shows no difference in pain levels between depressed TMD patients who received intervention for depression and nondepressed individuals with TMD.25 Most significantly, it has recently been discovered that individuals with TMD are more likely to have an abnormality in the serotonin transporter gene, which indicates that there may be an inherited predisposition to abnormal pain processing in at least some TMD patients.26

Self-care measures for myogenous TMD causing myofascial pain include the use of moist heat, avoidance of chewing gum, and in marked cases, a soft diet. Self-awareness of clenching, which can be difficult to reinforce, is important in order to reduce this behavior. Physical therapy or relaxation training measures may be of assistance. For a discussion of manual techniques used in the treatment of TMD, see Chapter 6.

Low Pressure Headaches

The condition that may well be more common in the setting of whiplash is the low pressure headache due to a subacute CSF leak. This will present with essentially the same symptoms as the acute CSF leak headache but is less likely to be affected by position. There is considerable symptom overlap between low pressure headaches, also known as intracranial hypotension, and whiplash-associated headache. An interesting study, noting this overlap, looked at 66 patients with chronic whiplash-associated disorder and performed radioisotope cisternography in all in search of a CSF leak. A surprising 56% (37) were positive. Symptoms in the positive group were—in addition to headache—dizziness, memory loss, visual impairment, and nausea. Symptoms were markedly improved after epidural blood patch, and half were able to return to work.27

The work-up of low pressure headache should begin with cranial MRI with contrast. Pachymeningeal enhancement can be seen in intracranial hypotension but is not always present. If clinical suspicion persists, the next diagnostic study to be pursued is either myelography or cisternography. Lumbar puncture will need to be performed for either of these studies, and it is essential that an opening pressure be measured. A pressure of less than 60 mm H2O in the sitting position is diagnostic of intracranial hypotension.9 Low pressure headaches tend to be resistant to medication and are treated with an epidural blood patch.

Headache with Autonomic Symptoms

Although infrequent, sometimes headache syndromes with autonomic features can be seen in the setting of either posttraumatic or whiplash-associated headaches. Both cluster headache and hemicrania continua have been reported.28,29

Cluster headache can also occur as a consequence of trauma, and has been reported in the setting of whiplash as well as head injury.29 Cluster headache is a severe headache, sometimes colloquially known as “the suicide headache” because of the excruciating nature of the pain that occurs during attacks. Cluster headache is so named because of the periodicity of headache attacks, which often occur in clusters. Headaches tend to be relatively short, usually lasting 30 to 60 minutes, although they may last up to 3 hours. It is common for cluster headache sufferers to experience two or three attacks per day; up to eight attacks per day have been noted. Often, one of the attacks will occur at night and may correlate with the first rapid eye movement (REM) period of sleep.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree