Hand Injuries

Allan Durkin

David Halpern

Richard D. Klein

The human hand is a marriage of form and function. It allows us to interact and react to our environment with efficiency and accuracy. Because of its vulnerable position, it is commonly injured at both work and play. Hand injuries are, for the most part, nonlethal, but they have potential for significant morbidity due to loss of function. This morbidity can largely be avoided by timely, appropriate management of these injuries. This chapter will review the fundamentals of hand anatomy and physiology, as well as the management principles for common injuries.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The human hand is a symphony of bones, muscles, nerves, and tendons, and each of these components is critical for efficient function.

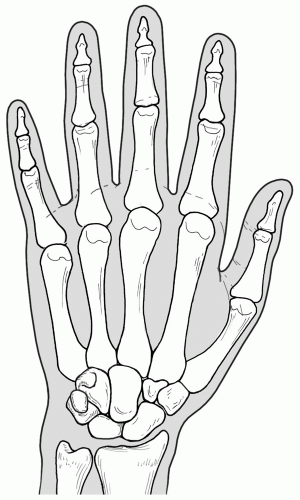

Bony Anatomy

The hand consists of five fingers-thumb, index, long, ring, and small fingers. Each digit holds two major neurovascular bundles on its ulnar and radial aspects. In these bundles lie the proper digital arteries, veins, and nerves. The bony platform of each finger consists of three nonsesamoid phalanx bones with the exception of the thumb, which harbors only two. The phalangeal bones of the hand articulate with five metacarpal bones, which connect the fingers to the base of the hand. The base of the hand consists of eight carpal bones. Traveling radial to ulnar, proximal to distal, the eight carpal bones are the: (i) scaphoid (ii) lunate, (iii) triquetrum, (iv) pisiform, (v) trapezium, (vi) trapezoid, (vii) capitate, and (viii) hamate bones (see Fig. 1). The carpal bones articulate with the radius and ulnar bones, and are supported laterally by a triangular shaped fibrocartilaginous complex, and anteriorly by a complex of ligaments extending from the distal radius into the base of the hand. An important bony structure is the Guyon canal. This bony conduit lies between the pisiform and the hook of the hamate bone. It provides an access route for the ulnar artery and nerve at the base of the hypothenar eminence.

Muscle Anatomy

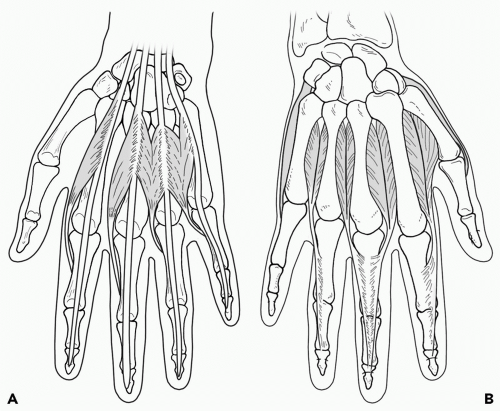

The hand is acted upon by both intrinsic and extrinsic muscles, the extrinsic muscles having the muscle belly within the forearm. The intrinsic muscles are the: (i) thenar, (ii) hypothenar, (iii) lumbrical, and (iv) the palmar and dorsal interossei muscle groups (see Fig. 2). There are three thenar muscles: (i) opponens pollicis, (ii) flexor pollicis brevis (deep and superficial heads), and (iii) abductor pollicis brevis. These three muscles are innervated by the median nerve. There are three hypothenar muscles: (i) abductor digiti minimi, (ii) flexor digiti minimi, and (iii) the opponens digiti minimi. These three muscles are innervated by the ulnar nerve. There are four lumbricals, two of which are innervated by the median nerve on the radial side of the hand, and two of which are innervated by the ulnar nerve on the ulnar side of the hand. These muscles originate from the flexor digitorum profundus as it courses from the wrist toward the distal phalanx. Cumulatively, these muscles provide flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joint, as well as extension at the interphalangeal joint.

The interosseous muscles are innervated exclusively by the ulnar nerve. They are divided into two groups-the dorsal and palmar interossei. The dorsal interossei consists of four muscles, and provides abduction of the index, middle, and ring fingers. The palmar interossei consists of three muscles, and allows adduction of the small, index, and ring fingers toward the middle finger.

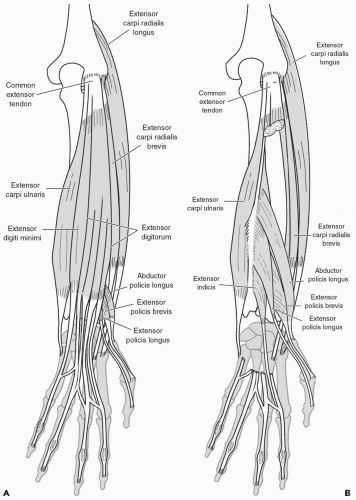

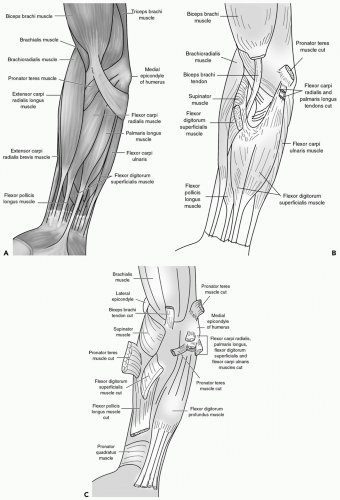

The extrinsic muscles of the hand impact on both wrist and digit motion. They are subclassified into anterior (flexor) (see Fig. 3) and posterior (extensor) compartment groups (see Fig. 4), with the intrinsic muscles having their muscle belly within the hand itself. The anterior compartment is conventionally divided into three separate muscle groups: (i) superficial, (ii) middle, and (iii) deep. With the exception of the palmaris longus tendon, all tendons of these muscles traverse the wrist deep to the flexor retinaculum. The superficial flexor muscles are the flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus. These muscles are innervated by the median nerve, with the exception of the flexor carpi ulnaris, which is innervated by the ulnar nerve. The middle flexors consist of the flexor digitorum superficialis, which is also innervated by the median nerve. This muscle terminates in four separate tendons, which themselves bifurcate at the middle phalanx of the medial four fingers (all except the thumb). At the middle phalanx, the tendon inserts into the medial and lateral surface of the bone. The chiasm generated by the split in the distal superficialis tendon creates a small conduit, through which the flexor digitorum profundus tendons travel to insert on the distal phalanx. The deep flexor muscles are the flexor digitorum profundus, the flexor pollicis longus, and the pronator teres. The flexor digitorum profundus is innervated by the median nerve on the radial side and the ulnar nerve on the ulnar side, whereas the flexor pollicis longus and pronator teres are innervated by the anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve.

The extensor (posterior) compartment is classified by function and is categorized as: (i) hand motion at level of wrist, (ii) finger motion, and (iii) thumb motion. All muscle tendons enter the hand deep to the extensor retinaculum. Hand motion at the wrist is generated by three muscles: (i) extensor carpi radialis longus, (ii) extensor carpi radialis brevis, and (iii) extensor carpi ulnaris. The extensor carpi radialis longus is innervated by the radial nerve, whereas

the two remaining muscles are innervated by the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. Finger motion is generated by three muscles: (i) extensor indicis, (ii) extensor digitorum profundus, and (iii) the extensor digiti minimi. These three muscles are exclusively innervated by the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. Thumb motion is generated by three muscles: (i) extensor pollicis brevis, (ii) abductor pollicis longus, and (iii) the extensor pollicis longus. These three muscles are also innervated by the posterior interosseous nerve. The anterior interosseous nerve is a branch of the median nerve, whereas the posterior interosseous nerves correspond to the deep branch of the radial nerve.

the two remaining muscles are innervated by the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. Finger motion is generated by three muscles: (i) extensor indicis, (ii) extensor digitorum profundus, and (iii) the extensor digiti minimi. These three muscles are exclusively innervated by the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. Thumb motion is generated by three muscles: (i) extensor pollicis brevis, (ii) abductor pollicis longus, and (iii) the extensor pollicis longus. These three muscles are also innervated by the posterior interosseous nerve. The anterior interosseous nerve is a branch of the median nerve, whereas the posterior interosseous nerves correspond to the deep branch of the radial nerve.

Figure 3 A: Superficial extrinsic flexors of the hand. B: Intermediate extrinsic flexors of the hand. C: Deep extrinsic flexors of the hand. |

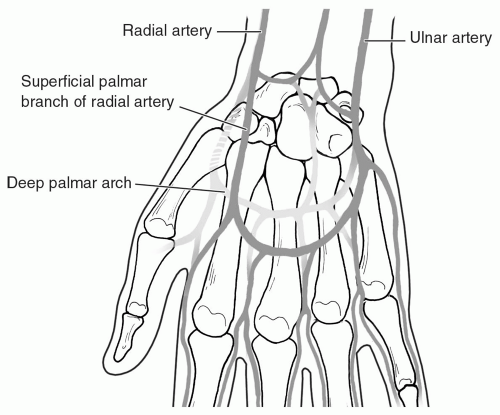

Vascular

The radial and ulnar arteries provide two major conduits for arterial inflow to the hand. (see Fig. 5) These arteries form two separate arterial arcades—the superficial and deep palmar arches. The superficial arch is primarily supplied by the ulnar artery, whereas the deep arch is primarily supplied by the radial artery. These arches supply the common digital

arteries and the princeps pollicis artery to the thumb. These common digital arteries and the princeps pollicis artery then bifurcate and extend medially and laterally along the long axis of each digit, thereby becoming the proper digital arteries. Loss of one digital bundle will not compromise digital vascular inflow resulting in clinically evident ischemia.

arteries and the princeps pollicis artery to the thumb. These common digital arteries and the princeps pollicis artery then bifurcate and extend medially and laterally along the long axis of each digit, thereby becoming the proper digital arteries. Loss of one digital bundle will not compromise digital vascular inflow resulting in clinically evident ischemia.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Injuries to the human hand are rarely life threatening. However, patients who have sustained injury to their hand commonly present with other injuries. It is crucial for the surgeon to not lose sight of this, and concentrate on an obvious hand injury, and undertriage simultaneous injury.

After completing standardized primary and secondary trauma surveys, and assuring that all life-threatening injuries have been addressed, an accurate history regarding the injury should be taken. Of note, the physician should determine early on as to whether the patient injured his/her dominant or nondominant hand. The physician should attempt to define the mechanism of injury (i.e., crush, laceration, burn, etc.), and its perceived effect by the patient. An attempt to define the exact position and orientation of the hand at the time of injury should be made. By so doing, significant clues toward injured internal structures can be determined. Next, define how the patient feels his/her hand. Do they have normal sensation and movement? If not, how does it differ? Again, an adequate catalog of these characteristics offers insight regarding internal damage. The magnitude of injury should also be addressed. Injury from engine-powered machinery will produce a deeper injury pattern in most cases than hand-powered machinery. The time of injury should be accurately recorded, as well as the time evaluated. This time interval can be critical, especially if ischemia is involved. The patient should be asked about any prior hand injuries. Finally, an accurate determination of pertinent medical comorbidities should be undertaken.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree