Chapter 13. Hand injuries

The hand is a complex structure and even a slight disturbance in one part can have serious effects on its function as a whole. Because the hand is so important to work, leisure and everyday living, hand injuries demand special care and attention.

Hand injuries can involve:

• Nerves.

• Bones.

• Joints.

• Tendons.

• Skin and soft tissue.

• Blood vessels.

Nerves

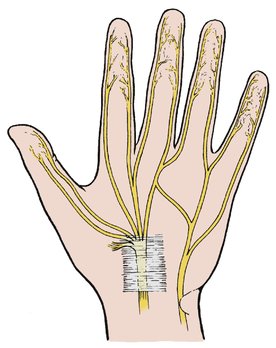

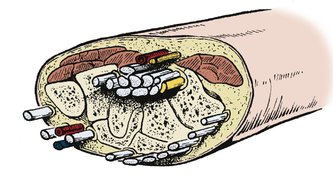

The different types of nerve lesion and their management are described on pages 109, 141 (Fig. 13.1).

|

| Fig. 13.1 Nerve supply to the palm of the hand. Note the position of the digital nerves and the median and ulnar nerves at the wrist, and the median nerve passing beneath the transverse carpal ligaments. |

Median nerve

The median nerve may be cut cleanly across at the wrist or palm by sharp objects or by falls through windows.

Treatment

These injuries are ideal for immediate repair; i.e. within 24 h of injury. The results are generally good, particularly in children, but complete recovery never occurs. The flexor tendons are usually injured at the same time and accurate repair of all the structures involved can be very difficult.

Ulnar nerve

The ulnar nerve can also be damaged in this way but it lies deeper than the median nerve and is protected by the tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris.

Digital nerves

The palmar digital nerves are very vulnerable and are cut if the patient grips a blade or a sharp object. The digital artery is usually damaged at the same time. Because the volar digital nerve supplies the pulp of the finger, injuries to it can seriously impair function.

Treatment

The cutaneous nerves on the dorsum of the finger, distal to the middle of the middle phalanx, are too small to repair. On the palmar surface the nerve is large enough to repair as far distally as the distal interphalangeal joint. Lesions proximal to these points should be repaired under magnification.

Crushed nerves and dirty wounds

Contaminated or untidy nerve lesions are not suitable for immediate repair.

Treatment

The ends of the nerve can be tagged with a marking suture and the nerve repaired when the wound has healed. The end of the nerve will then have a firm fibrous cap of epineurium, which must be removed before it can be repaired. The nerve must also be mobilized proximally and distally to give extra length.

Flexor tendons

Anatomy

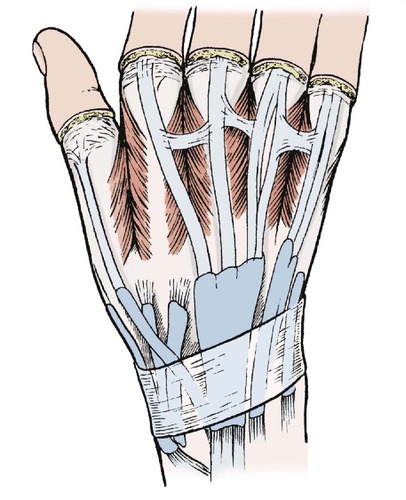

The flexor tendons run part of their course through synovial and fibrous sheaths. The fibrous sheaths, which are lined with synovium, run from the distal interphalangeal (d.i.p.) joints to the distal palmar skin crease and prevent the tendon ‘bowstringing’ when the finger is flexed.

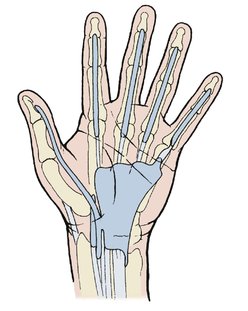

The synovial sheaths of the thumb and little fingers extend proximally through the carpal tunnel. The three central digits (index, middle and ring) have a separate flexor sheath in the fingers. There is also a sheath in the palm which extends proximal to the wrist (Fig. 13.2).

|

| Fig. 13.2 Tendon sheaths in the palm and wrist. |

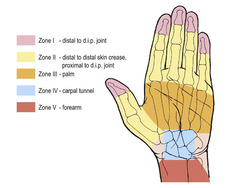

Sites of flexor tendon injury

Zone I: distal to d.i.p. joint.

Zone II: in the fingers.

Zone III: in the palm.

Zone IV: in the carpal tunnel.

Zone V: in the forearm.

Because of these complexities, flexor tendon injuries should be treated only by experienced surgeons.

Zone I: Lesions distal to the tendon sheath

Injuries distal to the d.i.p. joint lie outside the sheath.

Treatment

Zone I lesions can be treated by (1) tendon advancement, or (2) arthrodesis of the d.i.p. joint.

The cut end of the tendon can be advanced and reinserted on the distal phalanx. This may cause a slight flexion deformity.

In the thumb the advancement can be done in the forearm because the flexor pollicis longus has no connection with other flexors and its tendon can be separated from the muscle belly in the forearm and moved distally.

The results of surgery are better in the thumb than the fingers.

Early movement, active or passive, is important after any tendon repair and several devices are available to encourage this.

Zone II: Injuries in the fingers

Management of flexor injuries in the fingers depends on the tendons involved and the site of injury (Fig. 13.3). The first step is to decide which tendon has been damaged.

|

| Fig. 13.3 Flexor tendon injuries to the hand. |

Profundus and superficialis action can be distinguished by asking the patient to flex the distal phalanx with the middle phalanx held still (see Fig. 2.26). Only flexor profundus will do this because superficialis does not extend beyond the middle phalanx (Fig. 13.4).

|

| Fig. 13.4 The relationship of flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis. |

To assess superficialis, hold all the fingers down except the one that is to be tested and ask the patient to flex that finger. If the finger flexes at the proximal interphalangeal (p.i.p.) joint, superficialis is intact. Test this on your own hand.

Treatment

Division of superficialis and profundus. If the tendons are cut opposite the proximal or middle phalanx they can be treated either by meticulous primary repair by an experienced surgeon or by replacing the tendon with an autograft of another tendon, such as palmaris longus or plantaris. If both tendons are cut, both should be repaired.

Division of profundus alone. If the tendon is divided within 1 cm of its insertion the tendon can be pulled up, or ‘advanced’, and the cut end attached to the distal phalanx.

Zone III: Injuries in the palm

Division of the flexor tendons in the palm is less serious than division in the fingers because the repair can be done outside the fibrous or synovial sheaths.

Treatment

The tendons should be repaired meticulously by an experienced hand surgeon and early mobilization instituted.

Zone IV: Injuries in the carpal tunnel

Eleven flexor tendons (flexor digitorum superficialis (4), flexor digitorum profundus (4), flexor pollicis longus, flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor carpi radialis) cross the volar aspect of the wrist (Fig. 13.5). If all these are divided, there will be 22 cut tendon ends. If the median nerve is divided as well, there will be 24 structures, which must be carefully identified, and if each pair is joined there will be 12 suture lines very close together. However carefully repaired, the tendons and nerves may stick together and form a solid mass which restricts movement at the wrist.

|

| Fig. 13.5 Structures crossing the wrist. |

Treatment

The problem can be simplified by discarding those tendons that are not absolutely necessary. The flexor superficialis, for example, can be sacrificed if flexor profundus is working. Finger flexion will still be full and the risk of adhesions between superficialis and profundus outweigh the improvement of function that might be obtained by repairing both.

Zone V: Injuries in the forearm

Injuries in the forearm lie outside any sheath and can be accurately repaired more easily than elsewhere.

Treatment

The tendon ends are accurately identified and repaired, and early mobilization begun.

Contaminated wounds and crushing injuries

If the wound is untidy and dirty it must be debrided and all dead tissue removed. If the wound is untidy but clean it is sometimes better to excise the tendon and replace it with a Silastic rod, which can itself be replaced with a graft when the wound has healed.

If the wound is contaminated, a clean and well- healed wound must be obtained before definitive treatment is undertaken.

Aftercare

The hand should be mobilized actively and passively as soon as pain and swelling permit.

Extensor tendons

Anatomy

Because the extensor tendons only have a synovial sheath where they cross the wrist, the problems encountered in repairing flexor tendons in the fingers do not arise. The tendons are easily identified, repair is straightforward and the fingers can be mobilized after 3 or 4 weeks.

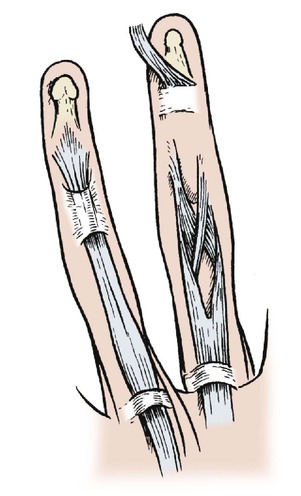

If the tendons are divided on the dorsum of the hand they cannot contract for more than a few millimetres because they are restricted by linking fibrous bands. Even without repair some extensor function will eventually return (Fig. 13.6).

|

| Fig. 13.6 Anatomy of the extensor tendons to show the tendon sheaths and extensor hoods. |

Treatment

Tendons divided on the dorsum of the hand should be repaired and the fingers splinted in extension for 3 weeks.

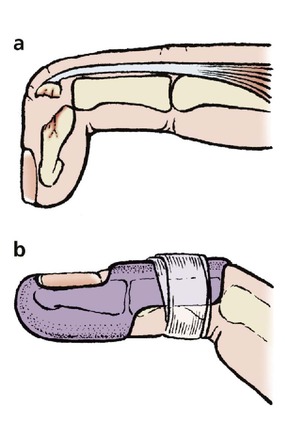

Mallet finger

Violent flexion injuries to, or lacerations across the back of, the d.i.p. joint can avulse or divide the insertion of the extensor digitorum longus at the base of the distal phalanx (Fig. 13.7 and Fig. 13.8).

|

| Fig. 13.7 (a) A mallet finger with avulsion of the extensor tendon from the distal phalanx; (b) a mallet finger splint holding the d.i.p. joint extended. |

|

| Fig. 13.8 Radiograph of a mallet finger. |

Untreated, the lesion causes the distal phalanx to droop and leaves a ‘mallet’ finger deformity. The condition is inconvenient but function improves without treatment and it is exceptional for the patient to be seriously troubled by the injury 12 months later.

Treatment

Although the results are acceptable without treatment, splintage can produce a better result. The finger should be immobilized for 6 weeks in a mallet finger splint which holds the d.i.p. joint hyperextended but allows movement at the p.i.p. joint (Fig. 13.7b). Some loss of active extension may persist.

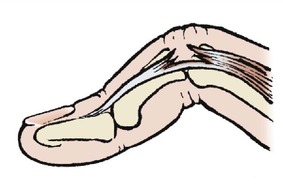

Boutonnière lesion

The central slip of the extensor expansion can be detached from its insertion at the base of the middle phalanx by a cut or by violent muscle contraction. This allows the two lateral slips to fall sideways and the p.i.p. joint to protrude between the two, which produces a characteristic deformity and may impair function (Fig. 13.9).

|

| Fig. 13.9 A boutonnière lesion of the p.i.p. joint. |

Treatment

The lesion should be splinted with the finger straight, but the results are imperfect. If the final disability justifies it, the two slips can be approximated to restore extension but flexion may be lost.

Blood vessels

Injuries at the wrist

Damage to the radial or ulnar arteries at the wrist causes severe arterial bleeding, which can be controlled by firm pressure and elevation.

Treatment

If both radial and ulnar arteries are ligated, ischaemia of the hand may result, and at least one, preferably the radial, should remain intact. If both treatment arteries are damaged, arterial repair is required.

Note: Be very careful when applying artery forceps near the wrist: arteries, nerves and tendons can all be damaged very easily.

Injuries in the palm

The deep palmar arch can be cut by penetrating injuries and causes serious bleeding.

Treatment

Bleeding must be stopped to avoid a large palmar haematoma and skin necrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree