Burn rehabilitation cannot be reviewed without a significant focus on the hand. Although the surface area of the hand is only 3%, the functional consequences cause extreme impairment. A comprehensive team approach from initial evaluation through long-term follow up is essential to maximize the functional outcome in this population.

Burn rehabilitation cannot be reviewed without a significant focus on the hand. Although the surface area of the hand is only 3%, the functional consequences are so impairing that any 2nd or 3rd degree hand burn is classified as a major burn injury, and referral to a burn center is recommended. Also, most individuals with large burns have some involvement of the hand. Contracture is a common complication following hand burns, and limitations in the hand result in significant functional limitations and decrease in quality of life. A comprehensive team approach from initial evaluation through long-term follow up is essential to maximize the functional outcome in this population. This team must work together to address wound closure edema, scar contracture, joint deformity, and functional issues.

Acute management

Close evaluation and management of the hand must be done in the very early stages following a burn injury. The surgical evaluation includes overall burn size and total body surface area (TBSA) to facilitate appropriate resuscitation. The hand-specific assessment must include a thorough evaluation of depth of burn. This is particularly important across the dorsal aspect of the digits to assess the risk of tendon exposure or rupture of the extensor mechanism. A neurologic examination should be performed for all patients, but particular attention should be paid in those with circumferential burns or electrical injuries.

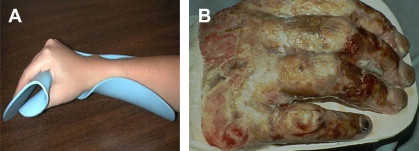

With the acute resuscitation there is significant fluid extravasation and associated edema that can lead to a claw hand deformity with hyperextension of the metacarpal phalangeal (MP) and flexion of proximal interphalangeal (PIP). Therefore the initial positioning should be in the antideformity position, which will also help control expanding edema. This is usually done with a classic volar positioning (VPS) splint ( Fig. 1 ). If the patient is unable to perform any active exercise, the splint is removed for range of motion with the therapist and for wound care but left in place the rest of the time. Once the patient is alert enough to begin actively using the hand, the splint can be used just at night. The MP hyperextension posture seen in a claw hand deformity is similar to the intrinsic minus hand associated with median and ulnar neuropathy. Differentiating between these two conditions is important, because the treatment approach is very different ( Fig. 2 ).

Positioning for those with hand burns is designed to keep MP flexion range of motion, prevent extensor mechanism rupture with PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) extension, and help control edema. Elevation of the hand is also helpful to limit edema. Splinting initially is primarily the use of the VPS as outlined previously. Once the wound is mostly closed, alternative splinting to maximize function should be prescribed.

Passive range of motion should begin following initial assessment and advanced to active assistive and active range of motion as the patient is more able to participate. If the burn appears to be deep full thickness, one must be aware of possible disruption of the extensor mechanism either by direct thermal injury or by ischemia. The extent of this injury is difficult to assess with overlying eschar. Therefore all full thickness hand burns should be treated as if the extensor mechanism is jeopardized. Range of motion can be continued using the tendon glide technique. This technique involves mobilizing a single joint while keeping the other joints in extension (ie, flexing the MP while keeping the PIP and DIP in extension, flexing the PIP with the MP and DIP in extension, or flexing the DIP with the MP and PIP in extension). This technique allows for some tendon sliding to decrease the risk of adhesion formation. The tendon should be kept moist, and combined flexion must be absolutely avoided, as this full fisting position can rupture the fragile extensor mechanism. Splinting allows removal for wound care but risks jeopardizing the tendon with patient movement when the splint is not in place. Finger casting leaving the DIP free allows for tendon glide stretching within the cast and provides protection from combined flexion ( Fig. 3 ). The downfall of this technique is that the cylindrical nature of the digit makes it difficult to keep the cast in place. Pinning is the most stable solution but may result in digit fusion, particularly if the pin is left in place for more than a few weeks. If the tendon is irreversibly ruptured and fusion is the goal, then the digit should be pinned in a functional position with the PIP in 30° of flexion and DIP in full extension. In these cases, aggressive range of the MP joint to regain flexion is essential for maximizing function.

Superficial or midpartial thickness hand burns heal spontaneously with little cosmetic or functional sequelea. This depth of burn usually does not require hospitalization. Also, isolated unilateral full-thickness hand burns can be managed on an outpatient basis until the time of surgery. For those with bilateral hand burns, hospitalization is usually recommended because of the difficulty of maintaining self-care independence with both hands in dressings. Also, earlier surgery allows the individual to regain functional independence sooner.

Early excision and grafting are the standard of care for treatment of full-thickness hand burns, but the definition of what is early continues to be debated. Obviously, wound closure decreases edema and helps maximize function, but this cannot be done at the expense of closing larger surfaces in an individual with a very large burn. Using a tourniquet at the time of excision limits blood loss. Tourniquet time and pressure should be monitored closely to avoid underlying tissue or neurologic injury. Full-thickness or split-thickness sheet grafting is recommended to maximize cosmetic and functional outcomes ( Fig. 4 ). If the extensor mechanism is exposed, it is likely that the graft will not take over this area. Traditional grafting followed by wound care often results in tendon adherence to the zone that healed by secondary intention. The use of an artificial dermal matrix can help prevent this but requires two surgical procedures, which may not be feasible for those with large burns. Digit amputation is required when the underlying tissue and bone are mummified. Other than in cases of high-voltage electrical injury, amputation is rarely emergent, and delays may help in maximizing length.

Outpatient care

Following hospital discharge, the rehabilitation program continues to address many of the ongoing issues associated with hand burns. Despite wound closure, persistent edema may continue to be problematic. Use of an off-the-shelf pressure glove combined with elevation may provide some relief. If the edema persists, an elastic pressure dressing can be used. This is an excellent way to decrease edema but may temporarily limit digit flexion ( Fig. 5 ). Custom gloves are a more long-term solution but are expensive and also interfere with functional tasks. A very small percentage of patients with edema develops a syndrome that resembles complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type 1. This is mostly seen in patients with partial-thickness burns who do not exercise and develop significant edema. This condition responds to oral steroids and range of motion with full resolution ( Fig. 6 ).

Range of motion continues to be an essential component of treatment and recovery. Active assistive range with sustained stretch at or near the point of skin blanching forces the skin cells to divide and lengthen. In general, 20 minutes in the sustained stretch position is recommended. Moisturizing before stretch decreases the risk of skin tears. Paraffin at 120°F moisturizes and can facilitate relaxation but does not necessarily increase the range of motion gains obtained with stretching alone. Although ultrasound has been recommended by some, there are no definitive studies showing it aides in improving hand range of motion after burn.

Splinting continues to be an adjuvant technique for maintaining scar stretch. The traditional VPS, which is the mainstay during hospitalization, is almost never the splint of choice for an outpatient. Flexion glove with or without an MP block is used to facilitate combined flexion ( Fig. 7 ). A palmer conformer is used for facilitating palmer abduction. Ulnar gutter is used to keep the fifth digit from drifting into abduction. Casting has the advantage and disadvantage of being nonremovable. It can give a better stretch for palmer tightness and facilitates compliance particularly in children.

Exercise and functional activities are very important components of treatment after hand burn. Strengthening can be done with putty, claw, weights, or activity simulation ( Fig. 8 ). Obtaining range of motion and doing activities as before injury is ideal, but when this is not possible, adaptive techniques should be taught to facilitate functional independence.

The hand has many common deformities, including web space contractures; fifth finger abduction deformity; metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint extension deformities; boutonnière, swan neck and mallet deformities; and palmer cupping. Contractures of the web spaces are common challenges following hand burn. First web space tightness is managed by conformer splinting with the thumb in radial abduction ( Fig. 9 ). The other webs are addressed by using elastomer or silicone conformers with counter pressure in the space between the digits ( Fig. 10 ). MCP extension deformities are treated with MP blocking splints or casting. The Boutonniere deformity occurs from rupture of the extensor hood at the PIP with volar migration of the central slips. This results in flexion of the PIP and hyperextension of the DIP. Ideally this would be prevented during the acute management, but if it does occur, hand function can be maintained by focusing on MP flexion, allowing the patient to achieve functional grasps ( Fig. 11 ). Although Boutonniere deformity can be corrected after traumatic injury, this is very difficult in the burned hand, because the integrity of the dorsal skin is marginal at best. Additionally, the tendon is usually contracted and scarred down. Swan neck deformity occurs as a result of lateral scar tissue and is difficult to fully correct. Mallet deformity can be partially corrected with splinting, casting, or pinning. Palmer cupping primarily occurs in children with hot contact burns to the palm ( Fig. 12 ). With partial thickness palm burns, a palmer conforming splint may hold the palm contour. Unfortunately, children have a tendency to pull the palm into adduction, and the short lever arm makes it difficult to get a good purchase for maintaining stretch within the splint. Therefore, casting may be the best approach. Of note, children less than age 2 have very little wrist contour, which makes it possible for them to pull their arm out of a short arm cast. If positioning is essential, then a long arm cast with the elbow flexed at 90° may be required.