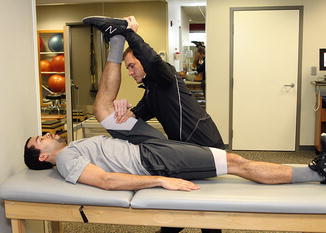

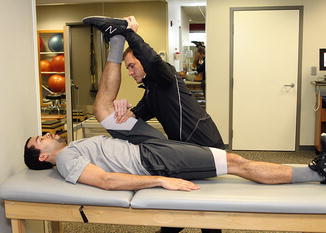

Fig. 12.1

Slump test

Limitations in hip flexor mobility should also be identified and addressed if present. Athletes with decreased hip extension mobility have been shown to compensate by increasing the amount of anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar extension during functional activities. This common compensation can potentially increase the length of the activated hamstring muscles during running and thus increase the risk of injury [20, 24, 26, 40].

Low-level agility exercises may be initiated during this phase of rehabilitation. The speed and intensity of exercises should be cautiously increased over time, with speed being progressed first. Exercises should initially focus on movements in the transverse and frontal planes. The individual can gradually be introduced to movements in the sagittal plane per pain response, being cautious not to overstretch the injured tissue. The clinician should begin to prepare the individual for return to recreational or sport participation during this phase. Examples of exercises that can be included are side shuffling, supine bridges with feet walkouts, rotating body bridges/planks, and lunge walking with trunk rotations [9]. Sport skills can be initiated as long as end-range lengthening of the hamstring musculature is avoided. Running speed is typically limited to 50 % of the athlete’s maximal running speed. Heiderscheit et al. reported that normal range of motion can be restored through the use of appropriate functional exercises and the reduction of pain and edema without the use of specific stretching of the hamstrings [9].

Sherry and Best compared the effectiveness of two different rehabilitation protocols for acute hamstring injuries. The authors analyzed the time needed to return to sport and re-injury rate during the first 2 weeks and throughout the first year after returning to sport. The results indicated that a rehab program including progressive agility and trunk stabilization exercise is more effective than a program emphasizing isolated hamstring flexibility and strengthening exercises for return to sports and re-injury prevention in those after an acute hamstring injury [22]. In addition, EMG studies have shown that the timing and activation patterns of the gluteus maximus and the hamstring muscles during running are similar [24, 40, 41]. Therefore, any deficiency in gluteus maximus strength and/or activation may place increased demands on the hamstring complex, increasing risk for an overuse injury [24]. More recent rehabilitation programs have been incorporating gluteus maximus activation and progressive strengthening such as double-leg to single-leg bridging and finally reintroducing gluteus maximus with hamstrings in exercises such as lunges and single-leg dead lifts [24, 42].

To progress an individual to the next phase of rehab, it is recommended that the individual meets the following criteria: (1) 5/5 hamstring strength with manual muscle testing when in prone position with knee at 90° of flexion [9] and pain-free resistive strength testing when in prone with 15° of knee flexion with <10 % deficit bilaterally; (2) negative slump test; (3) active knee extension test <10 % asymmetry and <20° of knee flexion; (4) modified Thomas test >5° and symmetrical to opposite extremity [24]; (5) ability to jog forward and backward at 50 % maximal speed without experiencing pain [9].

Phase III

The emphasis of the final phase of the rehabilitation program should be on preparing and returning the individual to the specific demands of their sport or desired activities. This phase should include more intense and aggressive sport-specific movements through full ranges of motion necessary for sport participation [9]. There are no range-of-motion restrictions during exercise as the individual should possess sufficient strength without pain. Therapeutic exercise should emphasize sport-specific movement patterns including change in direction and technical skills. The intensity of the trunk stabilization exercises should be progressed to include transverse plane motions and asymmetrical postures. Eccentric strengthening should be progressed to include end-range positions with gradually increasing resistance. Explosive acceleration and sprinting should be avoided and only included in rehabilitation program once athlete passes all return-to-sport criteria. [9]. See “Return-to-Sport Criteria and Testing” section regarding safe clearance of individual back to sport or recreational activities.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Surgical repair is considered the best option for acute hamstring ruptures [43]. This procedure has been reported to significantly improve the prognosis of those suffering a proximal hamstring rupture, but could affect their ability to return to previous activity level and sports, making the postoperative rehabilitation critically important [44]. The ultimate goal of surgical repair and the rehabilitation program is to return the patient to their prior level of activity as quickly as possible while minimizing the risk for re-injury [45]. There is little consistency between rehabilitation protocols following proximal hamstring tendon repairs, and there have been no multicenter randomized controlled trials comparing different guidelines published [45].

Preoperative care should include patient education and exercises to limit atrophy to surrounding musculature. The patient should be educated on the injury, upcoming surgical procedure, and the recovery/rehabilitation protocol. The patient should also be fit and educated on the proper use of axial crutches. There is no need for a preoperative brace, and the patient should be instructed not to attempt to stretch or strengthen the injured hamstring as this will increase reactivity at the proximal hamstring tendon and ischial tuberosity. It is recommended that the only exercises to be included in this period are gluteal and quadriceps isometrics to limit atrophy in these muscle groups [45].

Immediate Postoperative Period

Typically patients are not braced or immobilized after surgical repair as long as they can maintain a neutral position of the leg in order to limit excessive tension through the repaired tissue or surgical incision. There are no consistent recommendations between surgeons as far as the use of postoperative bracing. Askling et al. reported that no brace is necessary after surgery while Lefevre et al. recommended that patients to be immobilized by a simple splint with the hip in 30° of flexion [44, 45]. The patient should be instructed to use bilateral axial crutches in order to limit loading and force through the involved lower extremity. It is recommended that patients use crutches for 2 weeks in their home and for 5 weeks for community ambulation. Upon leaving the hospital it is also recommended that the patient be provided with toilet and bed elevation, high chair cushion, and long clutching tongs to prevent excessive tension through repaired hamstring during activities of daily living and self-care [45].

Week 1

During this early protective phase, the hamstring muscle group should be kept in a shortened and relaxed position to avoid excessive strain or tension on the repair site. The patient should avoid sitting directly on the ischial tuberosity except when using a raised toilet seat. The patient is permitted to be partial or toe-touch weight bearing with bilateral axial crutches at this time [44, 45]. The only exercises recommended during this period are isometric gluteal and quadriceps sets, ankle pumps, and assisted heel slides allowing no more than 30–45° of knee flexion. These exercises should be included in the patients early home exercise program [45].

Weeks 2–3

After the first postoperative week it is recommended that the individual attend formal physical therapy at a frequency of 1–2 times per week. If immobilized postoperatively, the patient would be placed in a custom knee brace allowing full knee flexion but limiting the last 30° of extension [44]. Once the patient can demonstrate 30° of hip flexion during a straight leg raise, the patient is permitted to ambulate weight bearing as tolerated with short step lengths while continuing to use bilateral axial crutches. The patient is instructed to add single-leg balance and progress to mini knee bends while in single-leg stance when able. Other exercises deemed safe during this period include isometric hamstring muscle contractions and passive knee flexion and extension range of motion while in prone position [45].

If the patient is able to complete exercises included in week 2 without increasing pain or reactive effusion, additional exercises may be added. The clinician should monitor the patient closely during and after exercise and should exercise caution with progression or additions of higher level exercises. Exercises that can be added in the third postoperative week are standing hamstring curls, stationary marching on thick pad, and heel raises [45].

Weeks 4–6

Typically, between the fourth and sixth postoperative week the patient may begin to utilize an upright stationary bike to improve range of motion and flexibility [44, 45]. The seat height should be set in a high position allowing the patient to reach 70° of hip flexion with 90° of knee flexion. At this time exercises from the first 3 weeks may be discontinued and more specific lower extremity strengthening exercises may commence. The patient should be monitored to ensure that exercises are performed with correct technique and performed slowly during this period. Isometric hamstring curls while seated and bridges can be added at this time [45].

If postoperative bracing was used, the patient would be permitted to be full weight bearing with full knee range of motion after 6 weeks [44]. At this point in the recovery phase, the emphasis should be on normalizing the patient’s gait pattern. Additional exercises including prone isometric hamstring contractions and higher level single-leg balance exercises are also included at this time. The patient can bias the medial or lateral hamstring muscles during prone hamstring isometrics by internally or externally rotating the leg, respectively [45].

Week 7+

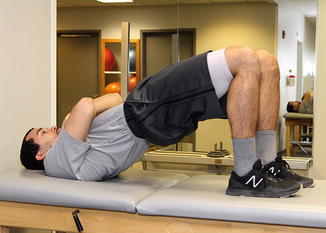

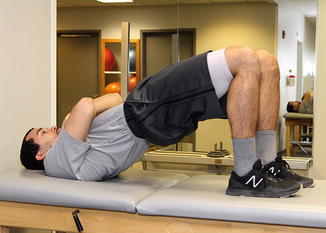

Lower extremity strengthening exercises can be progressed during this period. Technique should be monitored and progression of intensity or resistance should be based on patient’s tolerance and response to exercise. Suggested lower extremity strengthening exercises include mini squats, step downs, leg press, hip abductor strengthening while standing with use of tubing or machine, and higher level proprioceptive and balance training [46]. Hamstring curls in prone position on a machine can be initiated. The patient should start in prone position then progress to seated hamstring curls with hip positioned in 90° of flexion [46]. Other safe hamstring exercises which maintain the hamstring in midrange positions can be initiated as tolerated and include heel slides, double-leg bridges, and standing leg extensions [47] (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.2

Double-leg bridge

Eccentric strength training is recommended to begin at this time ensuring at least 2 days of rest a week. In order to progress the patient safely, eccentric exercises should begin in midranges and be performed bilaterally. Progressions of eccentric exercises may include single-leg forward leans, single-leg bridge lowering, and assisted Nordic curls [47]. The treating clinician should perform manual strength assessment with the patient in a prone position with the knee and hip extended. This assessment should be performed on a weekly basis to determine progress. As the rehab program progresses, other testing positions should be included to assess for pain and strength deficits. A side-to-side comparison of strength and range of motion is recommended in order to identify impairments and asymmetry. Askling et al. recommend that patients should perform 2–4 hamstring exercises during each physical therapy or home training session focusing more on quality and control of the movement rather than quantity. Exercise should be monitored and patients should be educated regarding correct technique and form to limit compensatory movements. Patients will often demonstrate gluteus maximus, adductor magnus, and gastrocnemius activation to assist the weakened or dysfunctional hamstrings with hip or knee motion [45].

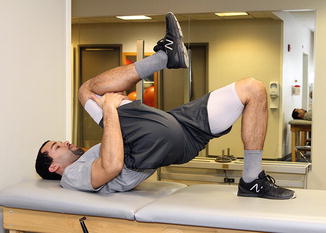

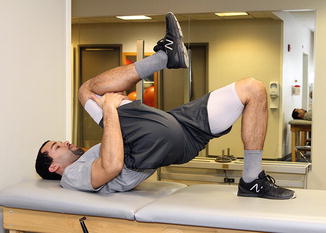

Between weeks 12 and 16 forward and backward fast walking and cautious light jogging with short strides may be initiated [44]. It is recommended that stationary jogging with high knee lifts be included gradually increasing intensity and duration over time. Bridges should be progressed to single-leg bridges at this time (Fig. 12.3). This exercise can be further progressed by moving the foot farther away from the hip leading to increased knee extension. Pendulums or forward/backward leg swings can be included to improve the flexibility of the hamstrings.

Fig. 12.3

Single-leg bridge

As the patient continues to progress, specific hamstring strengthening exercises should be combined with more complex movements such as lunges, squats, and different low-level plyometrics (Fig. 12.4). Additionally, hamstring strengthening can progress toward higher velocity strengthening in lengthened positions; an example would be weighted single-leg dead lifts [47] (Fig. 12.5).

Fig. 12.4

Forward lunge

Fig. 12.5

Single-leg dead lift

As the patient’s strength, flexibility, and tolerance to higher volumes and intensity of exercise increase, the clinician should begin to include more sport-specific movements or activities. During this transition from rehabilitation toward sport participation, the clinician should continue to assess the individual’s strength, range of motion, and confidence to ensure safe return to sport. Lefevre et al. recommended that regular sport activities could be started between postoperative weeks 16 and 32 [44]. In addition to general time guidelines, Askling et al. state that patients should demonstrate the ability to complete jumping, running, and cutting activities without pain, stiffness, or feelings of decreased confidence or insecurity before returning to pre-injury sport activities [45]. See “Return-to-Sport Criteria and Testing” section for criteria for RTS progression.

Return-to-Sport Criteria and Testing

Many athletes who complete a rehabilitation program will demonstrate full range of motion and strength as assessed manually clinically. However the re-injury rate after hamstring strains remains high especially in the first couple weeks of returning to sport [4]. This had led many to question the rehabilitation programs and criteria for returning athletes to sport after hamstring injuries.

As mentioned previously, a decreased length/tension relationship is a potential cause of hamstring injury and re-injury. Thus, Mendiguchia and Brughelli suggest a test for optimum angle of peak torque by testing knee flexion strength isokinetically at 60°/s (Fig. 12.6). Peak knee flexion at <28° and <8° of asymmetry between legs is recommended prior to return to sport [24]. Few clinics have access to an isokinetic strength testing system; thus a more relevant alternative is to perform the manual break test in a position near maximal functional length of the hamstring complex [48]. This test is described by having the patient first pull the hip to their chest while the opposite leg remains extended on the table. The examiner then passively extends the knee until soft tissue restriction is felt. The clinician slightly reduces the amount of tension by flexing the knee 10°. From this position the break test is performed and can be scored on grading scale or measured objectively with dynamometer [48] (Fig. 12.7).

Fig. 12.6

Isokinetic hamstring testing

Fig. 12.7

End-range position manual muscle test

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree