Hallux Valgus in the Athlete

Walter J. Pedowitz MD

David I. Pedowitz MD, MS

First ray bunion deformity causes pain, difficulty with normal shoe wear, and loss of the normal biomechanical integrity of the forefoot in locomotion.

Hallux valgus may result from a multitude of causes, which are divided into extrinsic and intrinsic events. The principal extrinsic cause is improperly fitted shoewear.

Generally patients with hallux valgus have markedly reduced pain when they remove their shoes, while patients with hallux rigidus have pain with shoes on or off.

Radiological studies for bunions should be done in the standing position. Any arthritis or deformity should be noted.

Initial treatment of bunions should always be conservative. Continued pain after conservative care, split shoe requirements, and deformity that greatly interferes with lifestyle are appropriate reasons for operation.

Bunion management in the high-performance athlete is challenging. Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) motion is essential in running, jumping, and dancing. Bunion surgery should be avoided in sprinters, high jumpers, pole vaulters, and ballet dancers because it will dramatically alter or terminate high performance.

Interdigital or Morton’s neuroma is an entrapment neuropathy of the plantar digital nerve, which is most common in the third intermetatarsal (IM) space. Trauma, bursal inflammation, a thickened IM ligament, a local ganglion cyst, or repetitive sports stress can cause it.

“Turf toe” refers to a severe sprain of the first metatarsal phalangeal joint (MTPJ) without concomitant dislocation or injury to the sesamoid complex.

Although most players have an uneventful return to athletics after a turf toe injury, management is facilitated by knowledge of the relevant anatomy, clinical signs, and the appropriate imaging in order to avoid chronic instability and/or pain.

Regardless of the etiology, the patient with metatarsalgia usually presents with pain in the distal forefoot exacerbated by activity that is relieved by rest. Because metatarsalgia is merely a symptom of a number of foot and ankle disorders, examination should include the entire foot and ankle.

Management of first ray bunion deformity continues to attract great attention in the orthopedic community. It causes pain, difficulty with normal shoe wear and loss of the normal biomechanical integrity of the fore foot in locomotion. With well over 100 repairs described in the literature, the current central issues still remain: Where is the deformity, what forces have caused it, does it cause disability, does it need to be fixed, and if so how?

In this subset of individuals the active athlete needs special consideration. Will operative intervention allow continuation of the sport and enhance performance? Or, on the other hand, will improvement of anatomy interfere with function and are all sports the same?

Stability, range of motion and weight transfer across the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint are provided by the interplay of the capsular ligamentous sling and the intrinsic shape of the joint. The metatarsal head in this joint, however, has no actual muscle insertions; therefore, failure of the supporting

structures may lead to deviation. Initial stability is maintained through strong fan shaped collateral ligaments from the head of the metatarsal to the base of the proximal phalanx medially and laterally. Similar ligaments also extend from the metatarsal head to the medial and lateral sesamoids.

structures may lead to deviation. Initial stability is maintained through strong fan shaped collateral ligaments from the head of the metatarsal to the base of the proximal phalanx medially and laterally. Similar ligaments also extend from the metatarsal head to the medial and lateral sesamoids.

The sesamoids, located within the split tendon of the flexor hallucis brevis, articulate with the inferior surface of the metatarsal head on either side of the cresta and are further stabilized medially by the abductor hallucis and laterally by the adductor hallucis. These attachments coalesce under the MTP joint to form the strong plantar plate, which inserts onto the base of the proximal phalanx. The flexor hallucis longus passes just inferior to the plantar plate toward its insertion on the distal phalanx. The extensor hallucis brevis and longus are stabilized dorsally by the foot alignment of the MTP joint and insert into the proximal phalanx and distal phalanx, respectively. The shapes of the first MTP joint and first metatarsocuneiform (MTC) joint help determine stability as well. Opposing flat surfaces are inherently stable, whereas rounder joints are more easily deviated (1,2).

Hallux valgus may result from a multitude of causes, which are divided into extrinsic and intrinsic events. The principal extrinsic cause is related to shoes. The incidence of hallux valgus has been shown to be higher in shoe-wearing societies than in populations that do not wear shoes. Women’s shoewear is often implicated as the cause of the high preponderance of hallux valgus found in females. In general, the outline of men’s feet is comparable to the outline of men’s shoes, resulting in no compression or constriction of the forefoot. Women’s shoes, however, do not conform to the outer dimensions of the foot and are, on average, 1.2 cm narrower than the forefoot (3). In addition, as the height of the heel rises, the forefoot force increases exponentially, driving the hallux into the narrow toe box of the shoe, leading to lateral deviation of the great toe (3,4,5,6).

Hypermobility of the first ray at the metatarsal cuneiform joint, metatarsus primus varus and abnormal metatarsal length are intrinsic causes of hallux valgus formation. Hyperpronation and/or relatively tight Achilles tendon leads to pronation of the first ray, causing stress on the medial aspect of the toe during normal gait.

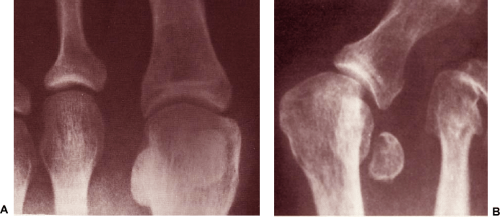

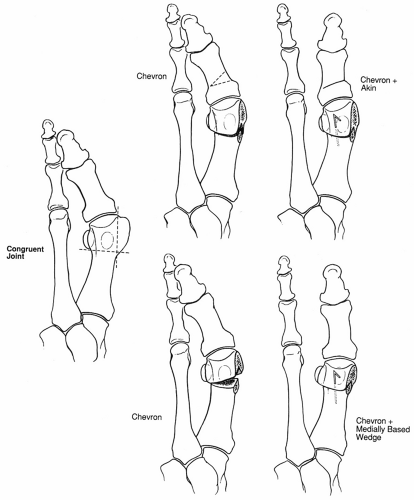

With valgus deviation of the great toe, the pull of the adductor hallucis muscle causes lateral deviation of the base of the proximal phalanx on the metatarsal head, which pushes the first metatarsal into greater varus. The medial capsule is attenuated, and the lateral structures contract. The transverse metatarsal ligament anchors the sesamoids to the second metatarsal, thus the sesamoids stay in place while the head of the first metatarsal moves medially, flattening the cresta. The result is mechanical derangement of the first MTP joint, including a prominent medial eminence, lateral subluxation of the base of the proximal phalanx, dissociation of the first metatarsal sesamoid complex, pronation of the hallux, and an increased angle between the first and second metatarsals. Pronation of the hallux varies with axial rotation of the first metatarsal. With increasing pes planus pronation, the first metatarsal rotates longitudinally, the orientation of the first MTP joint becomes oblique in relation to the floor, great toe function markedly decreases, and weight bearing is transferred laterally. Some bunion deformities involve congruent joints, meaning that there is lateral deviation of the articular surface of the first MTP joint without significant sesamoid displacement, hallux rotation, or sequential progression of the hallux valgus (Fig 53-1). Any attempt to move the proximal phalanx around on the articular surface of the metatarsal head would disrupt the normal joint relationship.

Lateral deviation of the great toe may also take place at the interphalangeal joint and is referred to as hallux valgus interphalangeus. This condition may be isolated or exist in conjunction with deviation at the MTP joint. All bunion deformities are not the same and a clear understanding and assessment of the underlying pathologic anatomy is critical to patient assessment.

The bunion patient will complain of swelling, redness, and pain on the inner side of the foot at the level of the MTP joint. Pain is more pronounced when wearing shoes and will diminish barefoot. Patients complain that they have difficulty finding a good fit in shoes.

This deformity is dynamic and the patient should be evaluated in both the weight-bearing and nonweight-bearing position. In the standing position the degree of forefoot spread, great toe angulation, and lessor toe deformity should be documented. The clinician must note whether the toe pads make contact with the ground while standing. The hindfoot and longitudinal arch must be assessed while standing and during gait.

Special attention is given to the first MTP joint. Axial rotation, angular deformity, and dorsiflexion are carefully measured. Normal dorsiflexion of the great toe is 70. Any MTP arthritis as noted by pain on range of motion of the great toe associated with limited motion should be documented. Generally patients with hallux valgus have markedly reduced pain when they remove their shoes, while patients with hallux rigidus have pain with shoes on or off. Instability at the first MTC is also recognized as important but difficult to assess. The physician can manually manipulate the MTC joint of the first ray to assess laxity, and the presence of a callus under the second metatarsal head my reveal diminished weight bearing of the great toe.

Radiologic Studies

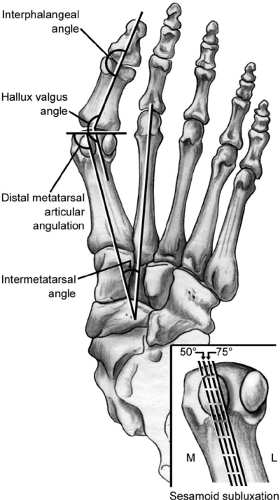

Radiological studies should be done in the standing position. Any arthritis or deformity should be noted and measurements should be calculated (Fig 53-2).

Increased angulation of the MTC joint and greater roundness of the metatarsal head indicates greater instability; a facet between the base of the first and second metatarsals suggests greater rigidity. Special attention should be paid to the distal metatarsal angulation in anticipating the need for an osteotomy. Measurements taken from radiographs can vary from examiner to examiner; and slight deviations in the angle of the beam, placement of the cassette, and rotation of the foot can significantly affect accuracy; therefore, these studies should be used as clinical guides and not absolute indications for surgical care (7,8).

Nonoperative Treatment

Initial treatment should always be conservative. With mild deformity, a patient who is willing to compromise with a properly fitting, low-heeled, extra-depth, or combined-last shoe, augmented with a good quality cushioned insole has a good chance to find comfort. With more significant deformity, a bunion last shoe with a broad toe box made of soft leather and a flexible sole will often relieve symptoms.

Continued pain after conservative care, split size shoe requirements (one foot greater in size than the other) and deformity that greatly interferes with lifestyle are appropriate reasons for operation. Cosmesis is not a realistic indicator and a risk benefit ratio needs to be assessed carefully. The American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society strongly condemns the cosmetic reconstruction of the foot.

Bunion management in the high-performance athlete is a unique challenge. Running, jumping, and dancing can put 275% of body weight across the MTP joint and increase shear force 50%; excellent MTP motion is essential (9). Accurate

correction of an obvious deformity can inadvertently cause decreased MTP motion and thus end a career. Bunion surgery should be avoided in sprinters, 400-m runners, high jumpers, pole vaulters, and ballet dancers (9). It should be made clear that surgical intervention may dramatically alter or terminate performance in the high performance athlete.

correction of an obvious deformity can inadvertently cause decreased MTP motion and thus end a career. Bunion surgery should be avoided in sprinters, 400-m runners, high jumpers, pole vaulters, and ballet dancers (9). It should be made clear that surgical intervention may dramatically alter or terminate performance in the high performance athlete.

Extreme dorsiflexion, however, is less of a concern in middle and long-distance runners and cyclists. If conservative care fails and the deformity prevents performance without severe limiting pain, surgery should be done.

Bunions may also be symptomatic in the teen and preteen athlete. They are more likely to have an adducted foot with an increased distal metatarsal articular angulation. If possible, reconstruction should be delayed until skeletal maturity and because their unique deformity is more likely to require osteotomy.

Operative Intervention

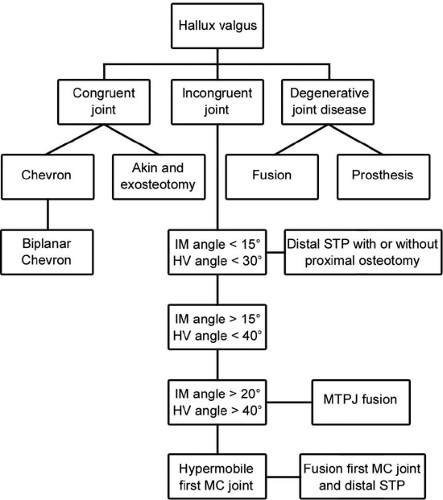

A surgeon considering operative intervention in a symptomatic bunion should be skilled in assessing the type of bunion and able to match it to an operative procedure with a high rate of predictability and ease of salvage. A long first metatarsal, a long great toe, an adducted foot, and generalized ligamentous laxity are associated with higher rates of recurrence (Fig 53-3).

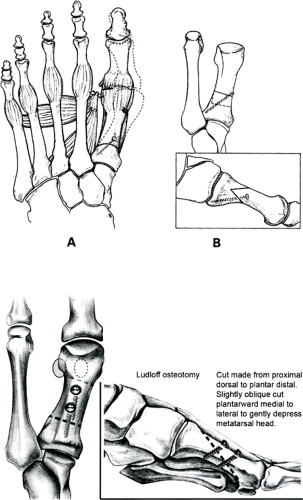

Soft tissue realignment of the first MTP joint will only correct the intermetatarsal (IM) angle about 5 degrees. Combined with a medial eminence resection of the distal first metatarsal this will correct only a mild deformity.

A chevron osteotomy, which involves a medial capsulloraphy, chevron shaped osteotomy with about 4 mm of lateral displacement of the metatarsal head, will correct an IM angle up to 15 degrees. For an incongruent joint a medially based wedge is taken out of the osteotomy site to better align the joint (Fig 53-4).

For greater angular deviation of the first metatarsal with significant hallux valgus, a distal soft tissue release involving proximal transfer of the adductor to the metatarsal neck, lateral sesamoid and IM ligament recession, and medial capsular reefing is combined with a proximal osteotomy of the first metatarsal to close the IM angle (Fig 53-5); however, a proximal osteotomy will stiffen the forefoot and transfer force to the hindfoot and ankle in athletic pursuit.

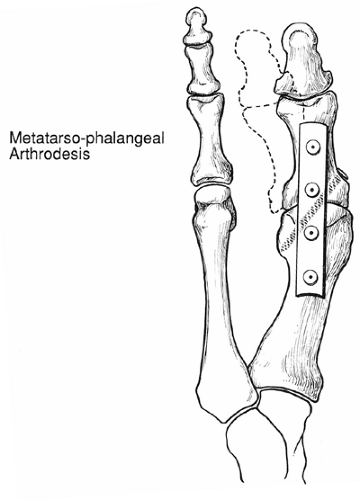

With significant arthritis of the great toe MTP joint, arthrodesis will give the greatest chance of returning to sports including doubles tennis, jogging, golf, ballroom dancing, and cycling (Fig 53-6). Silastic implants to the MTP joint have also been suggested for arthritis; however, it is generally thought that they will not hold up well or give the biomechanical support needed for active sports activity.

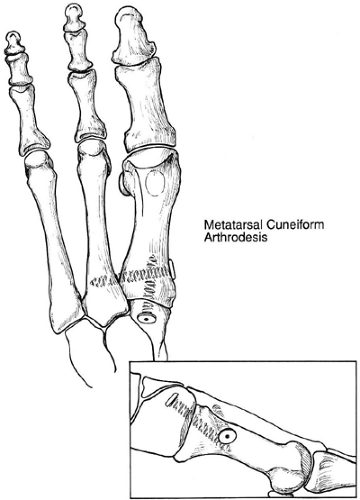

With documented instability of the MTC joint a distal soft tissue release plus a MTC arthrodesis is the procedure of choice (Fig 53-7). The instability itself is recognized as being hard to determine. Plain radiographs showing a hyperacute MTC angle or a curved distal first cuneiform articulation are suggestive. Arthritis at the first MTC articulation is diagnostic. A callus under the second metatarsal head may indicate decreased weight bearing by the first ray.

Interdigital or Morton’s neuroma is an entrapment neuropathy of the plantar digital nerve. Trauma, bursal inflammation, a thickened IM ligament, a local ganglion cyst,

or repetitive sports stress can cause it. Anatomically it usually involves a lateral branch of the medial plantar nerve and sometimes an additional branch from the lateral plantar nerve (Fig 53-8).

or repetitive sports stress can cause it. Anatomically it usually involves a lateral branch of the medial plantar nerve and sometimes an additional branch from the lateral plantar nerve (Fig 53-8).

Fig 53-7. Metatarsocuneiform (MTC) fusion. One must slightly flex and adduct the first metatarsal to obtain proper alignment. (From

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Pedowitz WJ. Bunion deformity. In: Pfeffer GB, Frey CC, eds. Current practice in foot and ankle surgery. New York: McGraw Hill; 1993;219–242;

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|