Washington state’s public workers’ compensation system has had a formal process for developing and implementing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines since 2007. Collaborating with the Industrial Insurance Medical Advisory Committee and clinicians from the medical community, the Office of the Medical Director has provided leadership and staff support necessary to develop guidelines that have improved outcomes and reduced the number of potentially harmful procedures. Guidelines are selected according to a prioritization schema and follow a development process consistent with that of the national Institute of Medicine. Evaluation criteria are also applied. Guidelines continue to be developed to provide clinical recommendations for optimizing care and reducing risk of harm.

Key points

- •

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines are developed and implemented in Washington state workers’ compensation using a rigorous and transparent process.

- •

Collaboration, dedicated staff, transparency, and process integrity are keys to success.

- •

Community clinicians partner with government in the development of these guidelines, leading to their broad acceptance.

Introduction

Evidence-based medicine has become the generally accepted approach in today’s health care system for determining what constitutes safe, effective, and cost-effective care, whereas in the past, it was more likely to be “eminence-based medicine” (ie, relying on opinions from senior clinicians without any standardized process and safeguards against bias). The caveat with evidence-based medicine is that the advent of new technologies, devices, surgical techniques, and emerging or alternative treatments outpaces the availability of high-quality unbiased research such that it is often insufficient to support the use of these health services. Formally developed clinical practice guidelines help fill this gap, although even rigorously developed guidelines do not ensure they will be accepted in clinical practice. Since 1992, when the national Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its report, “Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use,” the number of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has skyrocketed. The Guidelines International Network (GIN) was founded in 2002 and has since counted (6509 guidelines across 96 organizations in 79 countries as of May 2015 ). The challenge is translating the plethora of scientific evidence into recommendations that are useful for the everyday practitioner.

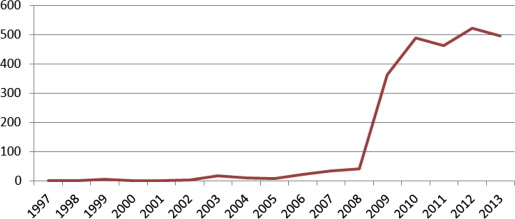

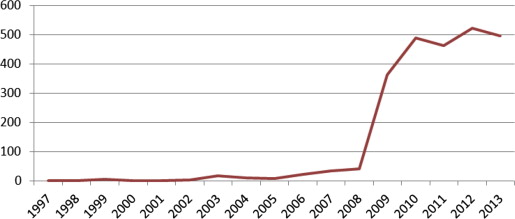

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), which is part of the US Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, maintains a central repository of national and international guidelines based on inclusion criteria established by the IOM in 2008. Fig. 1 illustrates this trend.

These guidelines are not a substitute for sound clinical decision making; rather, they inform and facilitate sound clinical decision making. If developed using a rigorous method, clinical practice guidelines can provide easy-to-follow criteria, algorithms, and decision-making tools that help optimize patient care, improve treatment outcomes, and prevent harm. Although they are based on scientific evidence, they also draw on the expertise of researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and myriad others who can dive deeply into critical questions and nuances that the literature may not elucidate. Although variation exists among expert opinions and experience, systematically synthesized information derived from high-quality studies and a consensus of expert opinion can enhance the individual provider’s ability to deliver high-quality care. In addition, by using a transparent, rigorous, and trustworthy process, guidelines can have greater relevance and credibility for the clinician and withstand scrutiny in the era of accountable care.

Since the 1980s, the Office of the Medical Director (OMD) in Washington state’s workers’ compensation system (part of Department of Labor and Industries [L&I]) has developed clinical practice guidelines (called medical treatment guidelines [MTGs]), and was the first workers’ compensation program to publish them on the NGC in 2002. To date, Colorado is the only other public workers’ compensation agency to post their guidelines on the NGC (starting in 2009). OMDs guidelines are used in the utilization review (UR) program and are regularly reviewed and updated as necessary. Furthermore, providers who treat Washington’s injured workers must be in our network and as such, are required by statute to use our MTGs (Revised Code of Washington 51.36.010). This article describes the rigorous guideline development process that OMD has refined during the last 7 years, which grew out of a model of collaboration and cooperation with our medical advisors, the health care community, and the public. These partnerships have been rewarding and crucial to the success of our work.

Introduction

Evidence-based medicine has become the generally accepted approach in today’s health care system for determining what constitutes safe, effective, and cost-effective care, whereas in the past, it was more likely to be “eminence-based medicine” (ie, relying on opinions from senior clinicians without any standardized process and safeguards against bias). The caveat with evidence-based medicine is that the advent of new technologies, devices, surgical techniques, and emerging or alternative treatments outpaces the availability of high-quality unbiased research such that it is often insufficient to support the use of these health services. Formally developed clinical practice guidelines help fill this gap, although even rigorously developed guidelines do not ensure they will be accepted in clinical practice. Since 1992, when the national Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its report, “Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use,” the number of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has skyrocketed. The Guidelines International Network (GIN) was founded in 2002 and has since counted (6509 guidelines across 96 organizations in 79 countries as of May 2015 ). The challenge is translating the plethora of scientific evidence into recommendations that are useful for the everyday practitioner.

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), which is part of the US Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, maintains a central repository of national and international guidelines based on inclusion criteria established by the IOM in 2008. Fig. 1 illustrates this trend.

These guidelines are not a substitute for sound clinical decision making; rather, they inform and facilitate sound clinical decision making. If developed using a rigorous method, clinical practice guidelines can provide easy-to-follow criteria, algorithms, and decision-making tools that help optimize patient care, improve treatment outcomes, and prevent harm. Although they are based on scientific evidence, they also draw on the expertise of researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and myriad others who can dive deeply into critical questions and nuances that the literature may not elucidate. Although variation exists among expert opinions and experience, systematically synthesized information derived from high-quality studies and a consensus of expert opinion can enhance the individual provider’s ability to deliver high-quality care. In addition, by using a transparent, rigorous, and trustworthy process, guidelines can have greater relevance and credibility for the clinician and withstand scrutiny in the era of accountable care.

Since the 1980s, the Office of the Medical Director (OMD) in Washington state’s workers’ compensation system (part of Department of Labor and Industries [L&I]) has developed clinical practice guidelines (called medical treatment guidelines [MTGs]), and was the first workers’ compensation program to publish them on the NGC in 2002. To date, Colorado is the only other public workers’ compensation agency to post their guidelines on the NGC (starting in 2009). OMDs guidelines are used in the utilization review (UR) program and are regularly reviewed and updated as necessary. Furthermore, providers who treat Washington’s injured workers must be in our network and as such, are required by statute to use our MTGs (Revised Code of Washington 51.36.010). This article describes the rigorous guideline development process that OMD has refined during the last 7 years, which grew out of a model of collaboration and cooperation with our medical advisors, the health care community, and the public. These partnerships have been rewarding and crucial to the success of our work.

How it started

In 2007, the Industrial Insurance Medical Advisory Committee (IIMAC) was formed through passage of agency-sponsored legislation (SSB 5801, CH 6 [2011]; codified as Revised Code of Washington 51.36.140). Fourteen physicians are nominated by their specialty societies or institutions and appointed by the L&I director to be members. These physicians are required to be practicing clinicians representing family medicine, orthopedics, neurology, neurosurgery, general surgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, psychiatry, internal medicine, osteopathic, pain medicine, and occupational medicine. At least two are required to have special expertise in evidence-based medicine. Although such a committee could have been formed by agency executive action, the statute provided two unique legal authorities: members are protected from legal action by the full extent of State legal authority; and members may be reimbursed for their work. In addition, all IIMAC meetings must be open to the public, so transparency is a built-in expectation.

The law also established an Industrial Insurance Chiropractic Advisory Committee (IICAC), charged with using evidence to ensure workers receive high-quality chiropractic care. IICAC members are also nominated from their professional societies and institutions, and they follow a similar rigorous process for developing conservative care “practice resources” that summarize available evidence for common occupational musculoskeletal conditions. These practice resources complement the IIMAC guidelines and are also included on the NGC Web site ( www.guidelines.gov ).

Led by an IIMAC member with expertise in the chosen topic, specially assigned subcommittees are formed to develop MTGs. Additional clinicians who are highly recognized leaders in the community are invited to complement subcommittee’s expertise. All clinical contributors to the guidelines must not have financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest, and outside sponsorship or funding of a guideline is never accepted. The effectiveness and popularity of the IIMAC and IICAC work have generated so much interest that there is a waiting list of providers who want to join them. The success of OMD is largely because of agency leadership that led to the statutory establishment of these partnerships with community providers, dedicated resources to build staff capacity, and integrity in the guideline development process. But the glue that binds these elements together to truly make it work is constructive engagement, trust, and high-quality work, making the highest level of collaboration possible ( Box 1 ). In February 2015, the IIMAC began work on its 15th guideline.