Essentials of Diagnosis

- Three pathologic hallmarks: granulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and necrosis.

- Classic clinical features are found in multiple organ systems:

- Nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, myalgias, weight loss, and fevers.

- Persistent upper respiratory tract and ear “infections” that do not respond to antibiotic therapy.

- Orbital pseudotumor, nearly always associated with chronic nasosinus conditions.

- Migratory pauciarticular or polyarticular arthritis.

- Nodular or cavitary lung lesions that are misdiagnosed initially as malignancies or infections.

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

- Nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, myalgias, weight loss, and fevers.

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) assays are helpful in diagnosis if positive by both immunofluorescence and enzyme immunoassay. A significant minority of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis are ANCA-negative, particularly those with “limited” disease.

General Considerations

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly called Wegener granulomatosis) is one of the most common forms of systemic vasculitis, with a reported annual incidence of 10 cases per million. The disease involves small- to medium-sized blood vessels (small more often than medium). GPA affects both the arterial and venous circulations, in contrast to polyarteritis nodosa, a disorder in which only arteries and muscular arterioles are affected. The cause of GPA is not known, but the prominence of upper and lower airway involvement suggests a response to an inhaled antigen. The disease is the prototype of conditions associated with ANCAs, an autoantibody generally believed to amplify rather than to initiate the inflammatory process. GPA occurs in people of all ethnic backgrounds but demonstrates a strong predilection for whites, particularly those of northern European ancestry. The male:female ratio is approximately 1:1. The mean age at diagnosis is 50 years. The elderly are often affected. The disease is less common but known to occur in children.

GPA typically presents in a subacute fashion. Patients complain of symptoms that appear to be innocuous at first, such as nasal stuffiness, “sinusitis,” and decreases in hearing. During this “prodrome,” attentive primary care providers may suspect and diagnose GPA before the onset of generalized disease. Such early recognition of GPA may prevent the disabling and disfiguring end-organ complications of this disorder, such as collapse of the nasal bridge, renal failure, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, and widespread infarctions of peripheral nerves.

Therapies for GPA are associated with substantial treatment-induced morbidity in both the short- and long-term. Careful follow-up and monitoring of basic laboratory tests (eg, regularly obtaining complete blood cell counts) may prevent some adverse effects of treatment or minimize their impact. More widespread use of rituximab in lieu of cyclophosphamide may diminish some of the long-term side effects associated with GPA treatment, particularly infertility and malignancy.

Clinical Findings

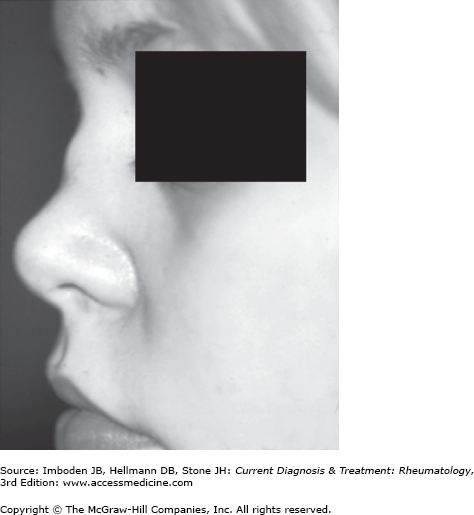

Approximately 90% of patients with GPA have nasal involvement. This is often the first disease manifestation. The typical symptoms are persistent rhinorrhea, unusually severe nasal obstruction, epistaxis, and bloody or brown nasal crusts (Table 32–1). Cartilaginous inflammation may lead to perforation of the nasal septum and collapse of the nasal bridge (a “saddle-nose” deformity) (Figure 32–1). Bony erosions of the sinus cavities are characteristic of GPA but only develop after long-standing disease (months).

| Organ | Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Nose | Persistent rhinorrhea; bloody, brown nasal crusts; nasal obstruction; nasal septal perforation; saddle-nose deformity |

| Sinuses | Sinusitis with radiologic evidence of bony erosions |

| Ears | Conductive hearing loss due to granulomatous inflammation in the middle ear; sensorineural hearing loss; mixed hearing loss common |

| Mouth | Strawberry gums; tongue or other oral ulcers; occasional purpuric lesions on palate |

| Eyes | Orbital pseudotumor; scleritis (often necrotizing); episcleritis; conjunctivitis; keratitis (risk of corneal melt); uveitis (anterior) |

| Trachea | Subglottic stenosis |

| Lungs | Nodular, cavitary lesions; nonspecific pulmonary infiltrates; alveolar hemorrhage; bronchial lesions |

| Heart | Occasional valvular lesions, usually not evident during life; pericarditis |

| Gastrointestinal | Mesenteric vasculitis uncommon; splenic involvement quite common but usually subclinical (detected as splenic infarcts on cross-sectional imaging) |

Both conductive and sensorineural forms of hearing loss occur in GPA. The usual pattern of auditory dysfunction is a mixed one, with the simultaneous occurrence of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Conductive hearing loss results from granulomatous involvement of the middle ear, most often leading to serous otitis media. Granulomatous inflammation in the middle ear may also compress the seventh cranial nerve as it courses through the middle ear cavity, leading to a peripheral facial nerve palsy. (This is often misdiagnosed as Bell palsy or Lyme disease.) Sensorineural hearing loss results from inner ear (cochlear) involvement and may also be associated with vestibular dysfunction (eg, nausea, vertigo, tinnitus). However, the sensorineural hearing loss associated with GPA is seldom profound. Additional information about sensorineural hearing loss is found in Chapter 68.

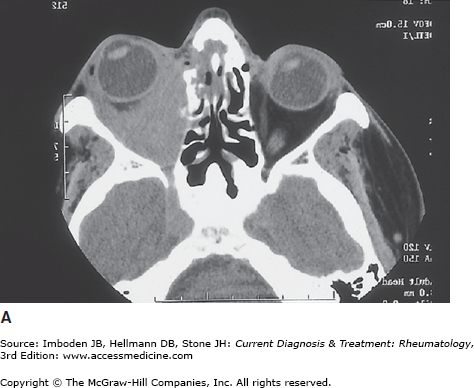

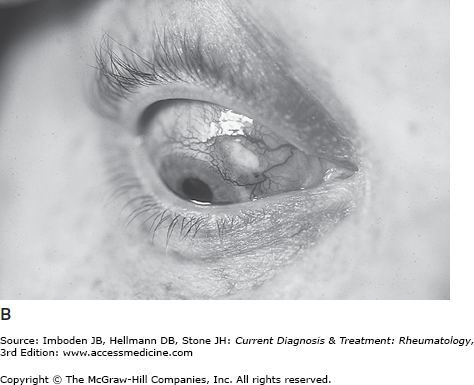

GPA may present with a variety of inflammatory lesions of the eye (Figure 32–2). Orbital pseudotumors in the retrobulbar space may lead to proptosis and visual loss through optic nerve ischemia (compression of the nerve’s blood supply by the space-occupying mass). Scleritis causes photophobia and painful, often nodular, scleral erythema. If unchecked, necrotizing scleritis may lead to scleral thinning, scleromalacia perforans, and visual loss. Peripheral keratitis may cause ulcerations on the margin of the cornea and lead to the syndrome of “corneal melt.”

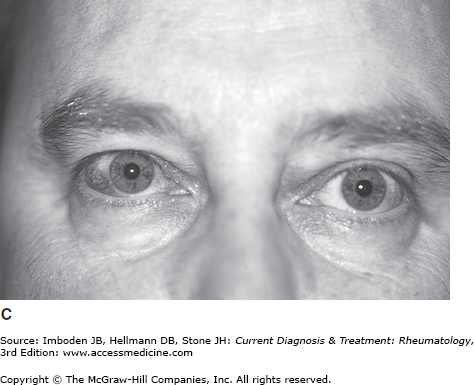

Figure 32–2.

A: CT scan of the orbit showing an orbital pseudotumor, leading to proptosis and visual loss. B: Scleritis with a marginal corneal ulceration. C: Painless erythema of the superficial surface of the eye—episcleritis—the most common ocular complication of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis).

Episcleritis and conjunctivitis constitute less serious ocular complications of GPA but are very common. Their occurrence may be the presenting symptom of the disease or the first manifestation of a flare. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction leads to poor outflow of tears such that the eyes in a patient with GPA are characteristically wet. Anterior uveitis is rare in GPA in comparison to other rheumatologic conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis (see Chapter 17), Behçet disease (see Chapter 38), and sarcoidosis (see Chapter 54). Central retinal artery occlusions are a known complication of this disorder, but other retinal lesions and posterior uveitis are uncommon.

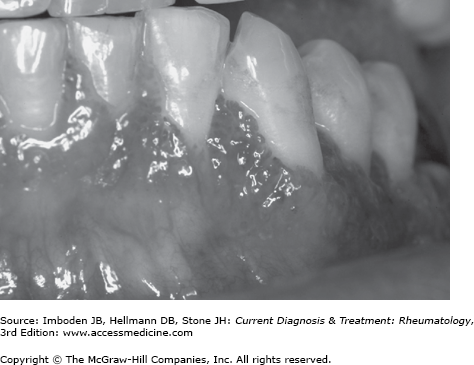

Two classic mouth lesions of GPA are gum inflammation (“strawberry gums” [Figure 32-3]) and tongue ulcers. The gum inflammation of GPA, which derives its name from the resemblance of the dental papillae to strawberries, is quite distinctive among rheumatologic conditions. The oral ulcerations of GPA, caused by medium-vessel vasculitis, typically occur on the lateral sides of the posterior tongue. Strawberry gums and tongue ulcers, both quite painful, respond promptly to glucocorticoids.

Subglottic stenosis, the result of tracheal inflammation and scarring below the vocal cords, is a potentially disabling manifestation that is largely specific to GPA (relapsing polychondritis can also cause this lesion). Subglottic involvement is often asymptomatic and may manifest itself only as a subtle hoarseness. With time, however, airway scarring and profound tracheal narrowing may occur. Pulmonary function tests with flow volume loops can show a fixed extrathoracic obstructive defect, but this may not become apparent until the process is advanced. Supraglottic disease, although substantially less common than subglottic stenosis, may also occur in GPA.

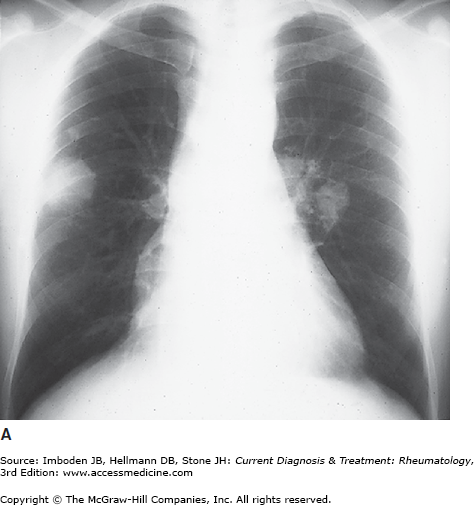

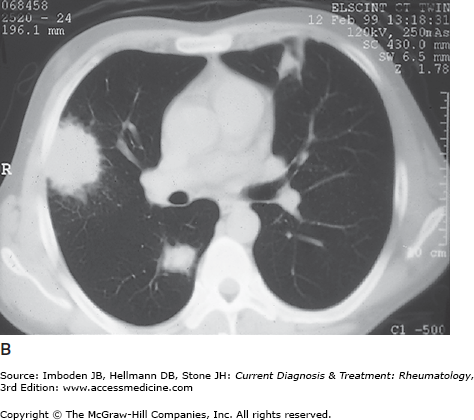

Approximately 80% of patients with GPA have pulmonary lesions during the course of their disease. Pulmonary symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and sometimes pleuritic chest pain. Lung lesions are often asymptomatic, however, and some are detectable only if chest imaging is performed. The most common radiologic findings are pulmonary infiltrates and nodules (Figure 32–4). The infiltrates, which may wax and wane, are often misdiagnosed initially as pneumonia. Single, large pulmonary nodules are often misdiagnosed as lung cancer. Nodules are usually multiple, bilateral, and often cavitary. Many nodules have peripheral locations and, if wedge-shaped, may be mistaken for pulmonary emboli.

Pulmonary capillaritis can lead to hemoptysis and rapidly changing alveolar infiltrates. Large airway disease leading to significant bronchial stenosis, similar to the findings found in subglottic stenosis, occurs in a minority of GPA patients. Large airway disease may be more common in pediatric than in adult GPA. Finally, venous thrombotic events (particularly deep venous thromboses) occur in a substantial proportion of patients, perhaps as a complication of the disease’s propensity to involve the venous circulation. These events tend to occur in close association with periods of active disease. Pulmonary emboli should be considered in the GPA patient in whom dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, or other compatible symptoms develop.

Renal disease, among the most ominous clinical manifestations of GPA, is often a marker for swift disease progression. Renal involvement, present in approximately 20% of patients with GPA at the time of diagnosis, develops eventually in a substantially higher portion of patients (up to 80%) during the course of the disease. The clinical presentation of renal disease in GPA is rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: hematuria, red blood cell casts, proteinuria (usually non-nephrotic), and rising serum creatinine. Without appropriate therapy, loss of renal function can ensue within days or weeks. More subacute courses of renal diseases also develop in some patients with GPA, particularly those with anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies (MPO-ANCA) as opposed to PR3-ANCA. GPA is also known to present with renal mass lesions that mimic malignancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree