Essentials of Diagnosis

- Caused by deposition of uric acid crystals and usually associated with hyperuricemia.

- Usually begins as an intermittent, acute monoarthritis, especially of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

- Over time, attacks become more frequent, less intense, and involve more joints.

- Diagnosed by demonstrating uric acid crystals in joint fluid.

- Extra-articular manifestations include tophi and renal stones.

- Arthritis responds to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or colchicine.

General Considerations

The underlying basis for gout is an increased total body urate pool. This is generally manifested as hyperuricemia, which is defined as a serum urate concentration more than 6.8 mg/dL. The concentration of 6.8mg/dL is important because fluids with urate content greater than that are supersaturated with urate, a condition that favors urate crystal precipitation.

At least 10% of asymptomatic Americans manifest hyperuricemia on at least one occasion during adulthood. Hyperuricemia may be even more common in Europe and in countries in the Far East.

The likelihood of developing symptomatic gout and the age at which that occurs correlates with the duration and magnitude of hyperuricemia. In one study, persons with urate levels between 7.0 and 8.0 mL/dL had a cumulative incidence of gouty arthritis of 3%, while those with urate levels >9.0 mL/dL had a 5-year cumulative incidence of 22%. However, hyperuricemia alone is not sufficient for the diagnosis of gout, and asymptomatic hyperuricemia in the absence of gout is not a disease. It appears that clinical gout develops in fewer than 1 in 4 hyperuricemic persons at any point.

Gout presents predominantly in men with a peak age of onset in the fifth decade. The incidence of gout in women approaches that of men only after they have reached age 65 years. The onset of disease in men prior to adulthood or in women before menopause is quite rare and is almost always due to an inborn error of metabolism or congenital condition. The prevalence of self-reported gout is estimated to be 13.6 per 1000 men and 6.4 per 1000 women.

Hyperuricemia can result from increased urate production, decreased uric acid excretion by the kidneys, or a combination of the two mechanisms. Less than 5% of patients with gout are hyperuricemic because of urate overproduction. These persons can be recognized because they excrete more than 800 mg of uric acid in their urine during a 24-hour period. Those who excrete less uric acid than 800 mg are hyperuricemic because of impaired renal excretion. Defining individuals as “over-producers” or “underexcreters” is helpful in predicting whether the hyperuricemia is associated with a variety of acquired or genetic disorders (Table 44–1) and may be useful in some cases in determining the most appropriate treatment.

|

Pathogenesis

Hyperuricemia, defined as a serum urate level of 6.8 mg/dL or greater, is the necessary precursor for the development of gout. When individuals are hyperuricemic, conditions exist such that urate crystals can precipitate in and around joint tissues. Without intervention, crystal precipitation continues forming larger and larger aggregates of crystals, termed “tophi.” An attack of acute gout follows the ingestion of urate crystals by monocytes and synoviocytes. Uncoated urate crystals are endocytosed by and activate monocytes. Inside the cells, they are processed through Toll-like receptors with result of pre-IL-1 production. The NALP-3 inflammasomes are also activated resulting in caspace-1 formation and the conversion of pre-IL-1 to IL-1 and the generation of a variety of other cytokines, adhesion molecules and chemotactic agents. The result is a very acutely inflamed joint.

The acute inflammatory response resolves spontaneously over 10–14 days. As the monocytes mature into macrophages, they switch from producing pro-inflammatory cytokines to anti-inflammatory cytokines like transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. In addition, large proteins (such as apolipoprotein B) that normally do not have access to the synovial fluid can enter the joint space because of the vasodilation and increased vascular permeability of the acute inflammatory response. These proteins coat the crystals and have an anti-phlogistic effect.

In between attacks, the tophi continue to enlarge. They are surrounded by a mantle of macrophages that are releasing cytokines and enzymes. This chronic inflammatory response is responsible for eroding bone and cartilage and causes a secondary degenerative joint disease. With enough cartilage degeneration, chronic arthritis that is symptomatically identical to primary osteoarthritis develops.

Clinical Findings

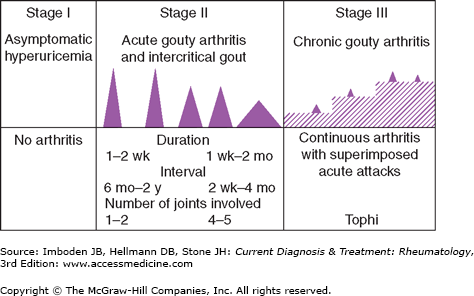

The natural history of gout can be divided into three distinct stages (Figure 44–1):

Asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

Acute and intermittent (or intercritical) gout.

Chronic tophaceous gout.

Although most untreated cases of gout progress to chronic tophaceous gout, the course varies considerably from one patient to another. Whereas some patients experience only one or two attacks of acute gouty arthritis during their lifetime, over 80% have a second flare within 2 years of the first. It is quite unusual for tophi to develop in a patient with no history of acute gouty arthritis.

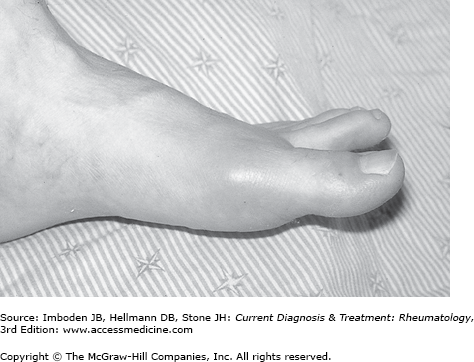

The initial episode of acute gouty arthritis usually follows 10–30 years of asymptomatic hyperuricemia, and there is no evidence that damage occurs to any organ system during that time. Just why and when the first attack of gout occurs in susceptible persons remains a mystery. Although some patients experience prodromal episodes of mild discomfort, the onset of a gouty attack is usually heralded by the rapid onset of exquisite pain associated with warmth, swelling, and erythema of the affected joint (Figure 44–2). The pain escalates from the faintest twinges to its most intense level over an 8- to 12-hour period. Initial attacks usually affect only one joint, and in half the patients, the first attack involves the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Other joints frequently involved in the early stage of gout include the midfoot, ankle, heel, and knee. The wrist, fingers, and elbows are more typical sites of attacks later in the course of the disease. The intensity of the pain is such that patients cannot stand even the weight of a bed sheet on the affected part and most find it difficult or impossible to walk when the lower extremities are involved in an acute attack. The acute attack may be accompanied by fever, chills, and malaise. Cutaneous erythema associated with the attack may extend beyond the involved joint and resemble cellulitis. Desquamation of the skin may occur as the attack resolves.

Symptoms resolve quickly with appropriate treatment, but even untreated, an acute attack resolves spontaneously over 1–2 weeks. With resolution of the attack, patients enter an interval termed the “intercritical period” when they are again completely asymptomatic. Early in the intermittent stage, episodes of arthritis are infrequent and the intervals between the attacks vary from months to years. Over time, the attacks become more frequent, less acute in onset, longer in duration, and tend to involve more joints.

During the intercritical periods of acute intermittent gout, the previously involved joints are virtually free of symptoms. Despite this, monosodium urate crystal deposition continues and tophi increase in size. Urate crystals often can be identified in the synovial fluid despite the absence of symptoms and erosive changes indicative of bony tophi begin to appear on radiographs.

Although the reasons why acute gout develops when it does are not clear, attacks tend to be associated with rapid increases, and more often decreases, in the concentration of urate in synovial fluid. These concentrations mirror the fluctuations seen in the serum. Accordingly, a person may experience a sudden drop in the serum urate level leading to an acute attack, and therefore is found to be normouricemic when blood is tested at that time. Trauma, alcohol ingestion, and the use of certain drugs are known to trigger gout attacks as well. Gouty attacks not infrequently occur as a person is recovering from an alcoholic binge. Drugs known to precipitate attacks do so by rapidly raising or lowering serum urate levels. Candidate agents include diuretics, salicylates, radiographic contrast agents, and specific urate-lowering drugs (probenecid, allopurinol, febuxostat, and pegloticase). It is believed that these fluctuations in urate levels destabilize tophi in the gouty synovium. The sudden addition of urate to them may render them unstable, or the sudden lowering of the urate concentration may cause partial dissolution and instability. As the microtophi break apart, crystals are shed into the synovial fluid and the gouty attack is initiated (see above).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree