CHAPTER 40 Glenoid Component

Problems with the glenoid are a common indication for revision arthroplasty. Such problems include failure of previously implanted glenoid components from total shoulder arthroplasty and osseous glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty. Frequently, glenoid problems involve substantial osseous compromise and require complex reconstruction. The ability to deal with these glenoid problems is necessary to successfully treat many cases of failed shoulder arthroplasty. Treatment of the various types of glenoid problems are addressed in detail in this chapter.

GLENOID REVISION NOT REQUIRING A BONE GRAFT

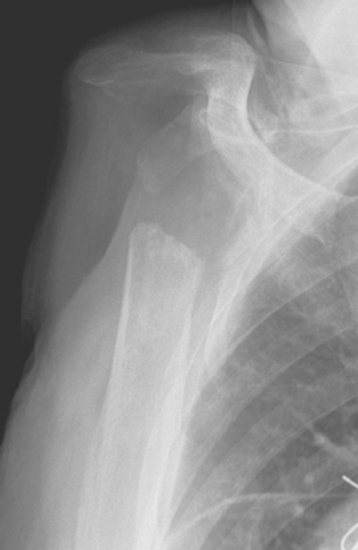

Glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty is a common indication for revision arthroplasty and occurs in two situations: (1) in patients with rotator cuff deficiency and superior glenoid erosion coupled with static superior (or anterior superior) humeral migration (Fig. 40-1) and (2) in patients with an intact rotator cuff and painful symptomatic humeral erosion that is central, anterior, or posterior (Fig. 40-2). Usually, the erosion is not severe enough to require a bone graft, but the surgeon should first determine the severity of the osseous glenoid defect with a preoperative computed tomogram (Fig. 40-3).

Figure 40-1 A and B, Anterior superior escape of a hemiarthroplasty without significant glenoid bone loss.

Unconstrained Shoulder Arthroplasty Cases Not Requiring a Glenoid Bone Graft

In patients with glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty and a functional rotator cuff, revision surgery from hemiarthroplasty to total shoulder arthroplasty is performed similar to cases of primary unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty. In such cases, if the humeral component is properly sized and positioned, the surgeon may be able to retain the humeral stem while performing revision surgery. This almost always necessitates changing the humeral head of the modular implant. It is important to know preoperatively the type of implant that the patient had and the radius of curvature of the various head sizes of this implant. A different brand of glenoid component can be coupled with the previous humeral head component if prosthetic mismatch can be calculated and respected during revision arthroplasty (see Chapter 12 for discussion of prosthetic mismatch and its implications in unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty). In general, radial mismatch of greater than 5.5 mm and less than 10 mm should be respected and the glenoid component size selected accordingly. If the humeral component is not properly sized or positioned or if adequate glenoid exposure cannot be obtained because of the humeral stem, the humeral component should be removed as described in Chapter 38.

Once glenoid exposure is achieved, implantation of a glenoid component proceeds as in cases of primary unconstrained arthroplasty with either a keeled or pegged glenoid component (Fig. 40-4). The technique for insertion of an unconstrained glenoid component is detailed in Chapter 12.

Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Cases Not Requiring a Glenoid Bone Graft

In patients with glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty and a nonfunctional rotator cuff, revision surgery from hemiarthroplasty to reverse shoulder arthroplasty is performed similar to cases of primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In such cases the hemiarthroplasty component is removed and the glenoid exposed as described in Chapter 38. Implantation of a reverse glenoid component proceeds as in cases of primary reverse arthroplasty, as described later in this chapter and in detail in Chapter 29.

GLENOID REVISION REQUIRING A BONE GRAFT

In cases of hemiarthroplasty with moderate to severe glenoid osseous erosion and in cases of failure of a primary glenoid component, reconstruction of the glenoid with an autogenous iliac crest structural bone graft is indicated.1 Our previous experience with cancellous bone grafts, allografts, and bone graft substitutes resulted in a high rate of graft resorption and led us to the technique that we now use.

Unconstrained Shoulder Arthroplasty Cases Requiring a Glenoid Bone Graft

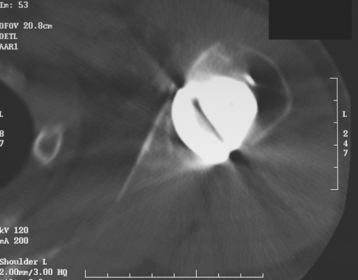

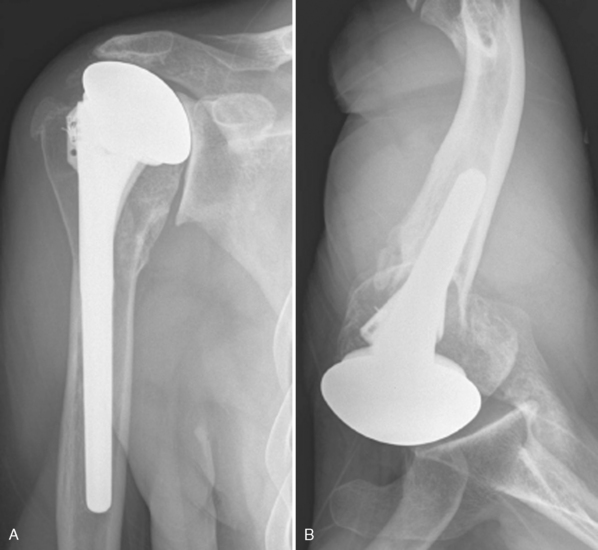

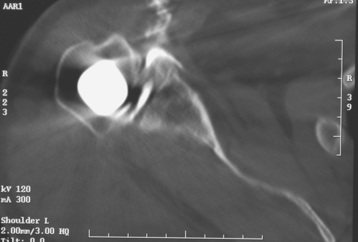

Rarely, moderate to severe osseous insufficiency of the glenoid occurs after hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder, and poor glenoid bone stock prohibits insertion of an unconstrained glenoid component (Fig. 40-5). In these cases two options exist: (1) conversion to resection arthroplasty by simple removal of the humeral component and (2) glenoid reconstruction with an iliac crest bone graft. Similarly, in patients with a failed glenoid component (loosening, component fracture), options include resection arthroplasty, removal of the glenoid component with retention of the humeral component, and glenoid reconstruction with an iliac crest bone graft (Fig. 40-6). We tell patients selected for glenoid reconstruction that we anticipate a second-stage operation for insertion of a polyethylene glenoid component once it is confirmed with computed tomography that the bone graft has been incorporated (Fig. 40-7), which occurs approximately 6 months after bone graft reconstruction. In patients who desire conversion to resection arthroplasty or removal of the glenoid component (usually elderly patients seeking only pain relief), this is easily accomplished by removing the humeral stem or glenoid component, or both, as described in Chapter 38 (Fig. 40-8).

Figure 40-7 Computed tomogram showing incorporation of an iliac crest bone graft used for reconstruction of the glenoid.

Figure 40-8 Patient undergoing resection arthroplasty for pain relief after failed shoulder arthroplasty.

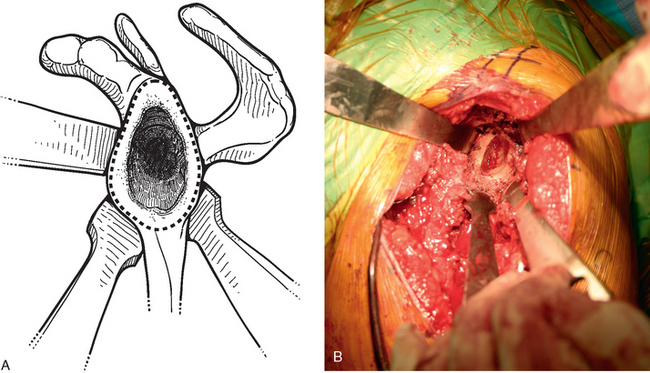

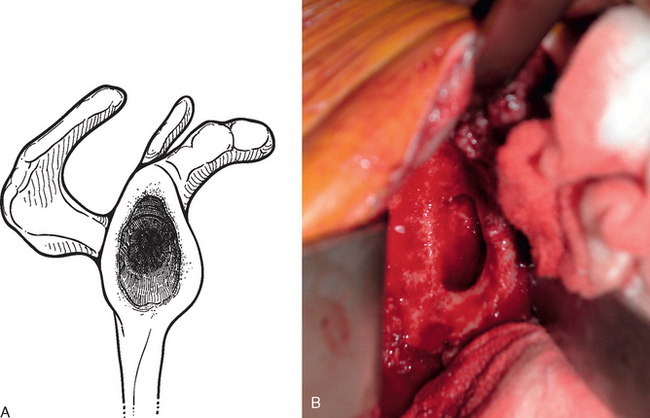

For glenoid reconstruction, an autogenous iliac crest bone graft is first harvested, as described later in this chapter. The glenoid is exposed, as previously described. Any soft tissue covering the remaining osseous glenoid is removed to define the limits of the glenoid osseous margins (Fig. 40-9). The area of deficiency is identified. If the deficiency is central, it may be possible to fashion the bone graft to fit the defect via an interference fit and eliminate the need for internal fixation (Fig. 40-10). For peripheral deficits, it is necessary to secure the bone graft with internal fixation to avoid migration. In anterior or posterior osseous insufficiency, we usually opt for cannulated, partially threaded 4.0-mm-diameter screws with washers placed through the bone graft and into the intact osseous glenoid. In central glenoid osseous insufficiency (not amenable to interference fit of the bone graft) and superior glenoid osseous insufficiency, we opt for graft fixation with 1.5 × 60-mm bioabsorbable fixation pins (SmartPin, Linvtec, Inc., Largo, FL).

Figure 40-9 A and B, The margins of the osseous glenoid are defined before reconstruction of the glenoid.

Figure 40-10 A and B, Central glenoid deficiency that can be treated by bone graft reconstruction with interference-fit fixation.

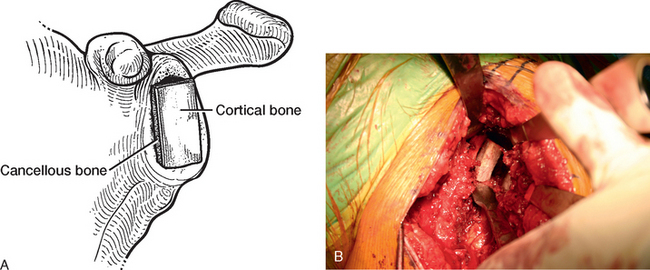

Contained Osseous Deficit

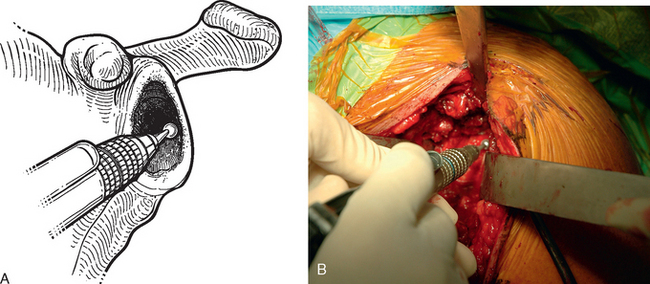

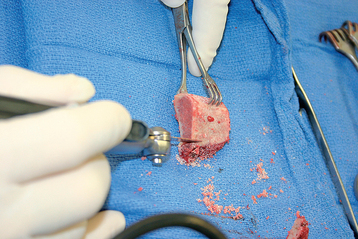

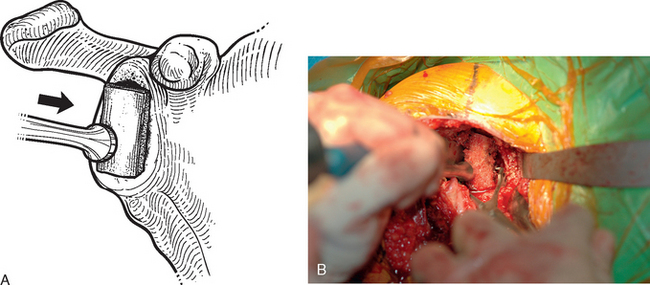

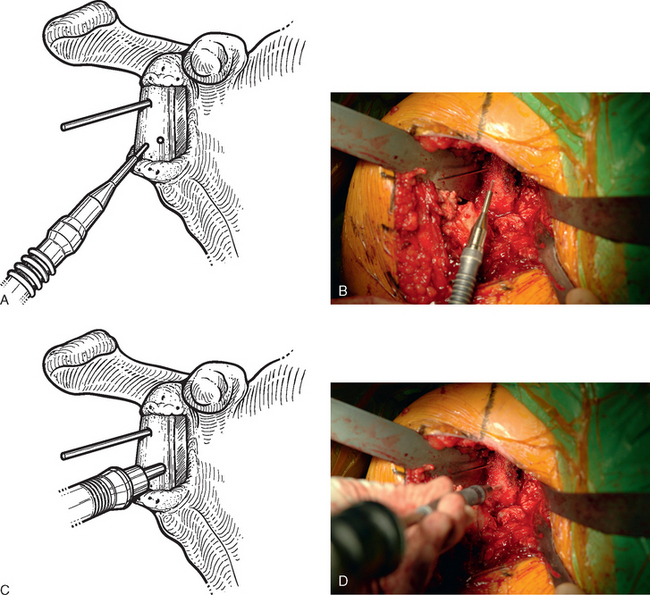

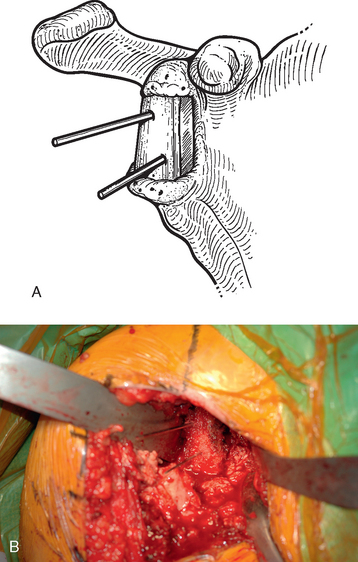

For interference-fit fixation of a central osseous deficit, the defect is prepared by lightly abrading the glenoid surface with a 5-mm round burr (Fig. 40-11). The tricortical iliac crest bone graft is trimmed with a cutting rongeur to a shape similar to the defect and slightly larger (Fig. 40-12). Cancellous bone is placed in the central defect, and the tricortical segment of the bone graft is placed in the defect and impacted into place with a large bone tamp until it is flush with the intact glenoid surface (Fig. 40-13). Care is taken to orient the tricortical graft so that a cortical surface faces laterally (Fig. 40-14). If the bone graft is not secured by interference fit, bioabsorbable fixation pins are used to prevent migration of the bone graft. This is done by first fixing the graft with two 0.062-inch Kirschner wires placed through the bone graft and into the native glenoid medially. These wires are intentionally placed so that they are not parallel to one another (Fig. 40-15). One of the wires is removed, and a bioabsorbable pin is advanced into the hole left by the Kirschner wire with the insertion device (Fig. 40-16). Another wire is used to create another hole in a direction and orientation different from that of the previous two holes, and another bioabsorbable pin is placed (Fig. 40-17). This process is repeated until a minimum of four pins have been placed. To enhance fixation, we avoid placing any of the pins parallel to one another. The residual pin tips are clipped flush with the bone graft with a large rongeur to complete fixation of the bone graft (Fig. 40-18). This same technique is used for superior defects. After contouring the bone graft to fit the defect and preparation of the base of the defect, the graft is fixated with multiple bioabsorbable pins (Fig. 40-19).

Figure 40-15 A and B, Kirschner wires placed before insertion of bioabsorbable pins for bone graft fixation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree