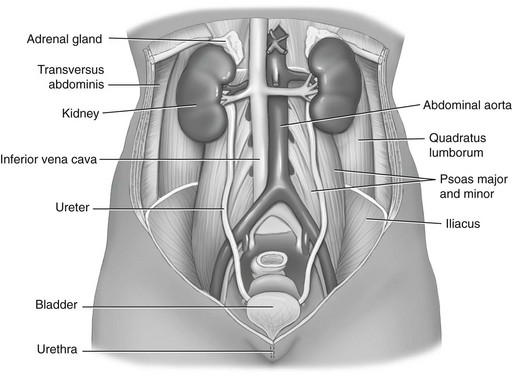

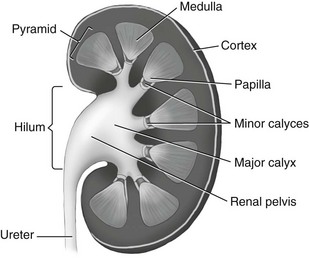

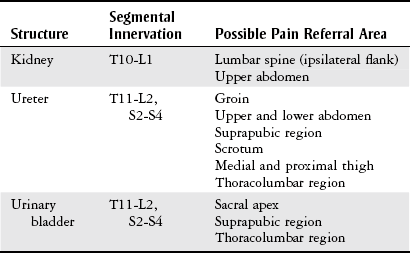

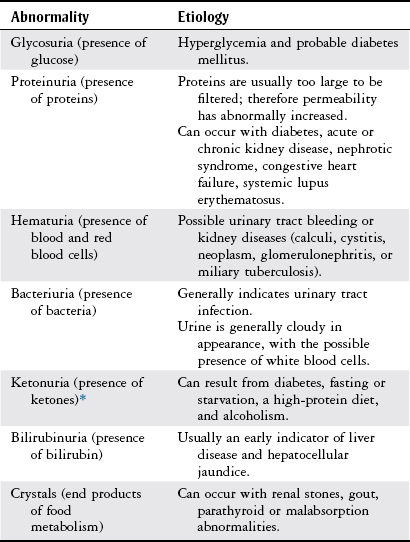

Chapter 9 The objectives of this chapter are the following: 1 Provide a basic understanding of the structure and function of the genitourinary system 2 Provide information about the clinical evaluation of the genitourinary system, including physical examination and diagnostic studies 3 Describe the various health conditions of the genitourinary system 4 Provide information about the management of genitourinary disorders, including renal replacement therapy and surgical procedures 5 Give guidelines for physical therapy management in patients with genitourinary diseases and disorders • Primary Prevention/Risk Reduction for Skeletal Demineralization: 4A • Impaired Aerobic Capacity/Endurance Associated with Deconditioning: 6B • Primary Prevention/Risk Reduction for Integumentary Disorders: 7A Please refer to Appendix A for a complete list of the preferred practice patterns, as individual patient conditions are highly variable and other practice patterns may be applicable. The regulation of fluid and electrolyte levels by the genitourinary system is an essential component of cellular and cardiovascular function. Imbalance of fluids, electrolytes, or both can lead to blood pressure changes or impaired metabolism that can ultimately influence the patient’s activity tolerance (see Chapter 15). Genitourinary structures can also cause pain that is referred to the abdomen and back. To help differentiate neuromuscular and skeletal dysfunction from systemic dysfunction, physical therapists need to be aware of pain referral patterns from these structures (Table 9-1). TABLE 9-1 Segmental Innervation and Pain Referral Areas of the Urinary System From Boissonault WG, Bass C: Pathological origins of trunk and neck pain: part 1. Pelvic and abdominal visceral disorders, J Orthop Phys Ther 12:194, 1990. The anatomy of the genitourinary system is shown in Figure 9-1. An expanded, frontal view of the kidney is shown in Figure 9-2. The functional unit of the kidney is the nephron, with approximately 1 million nephrons in each kidney. Urine is formed in the nephron through a process consisting of glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, and tubular secretion.1 The following are the primary functions of the genitourinary system2: • Excretion of cellular waste products (e.g., urea and creatinine [Cr],) through urine formation and micturition (voiding). • Regulation of blood volume by conserving or excreting fluids. • Electrolyte regulation by conserving or excreting minerals. • Acid-base balance regulation (H+ [acid] and HCO3− [base] ions are reabsorbed or excreted to maintain homeostasis). • Arterial blood pressure regulation. Sodium excretion and renin secretion maintain homeostasis. Renin is secreted from the kidneys during states of hypotension, which results in formation of angiotensin I and II. Angiotensin causes vasoconstriction to help increase blood pressure. Angiotensin also triggers the release of aldosterone, resulting in conservation of water by the kidney. • Erythropoietin secretion (necessary for stimulating red blood cell production). The brain stem controls micturition through the autonomic nervous system. Parasympathetic fibers stimulate voiding, whereas sympathetic fibers inhibit it. The internal urethral sphincter of the bladder and the external urethral sphincter of the urethra control flow of urine.3 Patients with suspected genitourinary pathology often present with characteristic complaints or subjective reports. Therefore a detailed history, thorough patient interview, review of the patient’s medical record, or a combination of these provides a good beginning to the diagnostic process for possible genitourinary system pathology. The description of pain can offer clues as to its source: renal pain can be described as aching and dull in nature, whereas urinary pain is generally described as colicky (occurring in wavelike spasms) and/or intermittent.4 Changes in voiding habits or a description of micturition patterns are also noted during patient history and are listed here4–6: • Dysuria (painful burning or discomfort during urination) • Nocturia (urinary frequency, more than once, at night) • Difficulty initiating urinary stream • Frequency (greater than every 2 hours) • Hesitancy (weak or interrupted stream) • Proteinuria (urine appears foamy) • Oliguria (very low urine output, such as less than 400 ml in a 24-hour period) The presence of abdominal or pelvic distention, peripheral edema, incisions, scars, tubes, drains, and catheters should be noted when performing patient inspection, because these may reflect current pathology and recent interventions. Refer to Chapter 18 for more information on medical equipment. The physical therapist must handle external tubes and drains carefully during positioning or functional mobility treatments. The kidneys and a distended bladder are the only palpable structures of the genitourinary system. Distention or inflammation of the kidneys results in sharp or dull pain (depending on severity) with palpation.6,8 Pain and tenderness that are present with fist percussion of the kidneys can be indicative of kidney infection or polycystic kidney disease. Fist percussion is performed by placing one hand along the costovertebral angle of the patient and striking the dorsal surface of that hand with a closed fist of the examiner’s other hand.6 Direct percussion with a closed fist may also be performed over the costovertebral angles. The patient should feel a “thud” but not pain or tenderness.8 Auscultation is performed to examine the blood flow to the kidneys from the abdominal aorta and the renal arteries. The presence of bruits (murmurs) can indicate impaired perfusion to the kidneys, which can lead to renal dysfunction. Placement of the stethoscope is generally in the area of the costovertebral angles and the four abdominal quadrants. Refer to Chapter 8, Figure 8-2, for a diagram of the abdominal quadrants.6,8 Urinalysis is a very common diagnostic tool used not only to examine the genitourinary system, but also to help evaluate for the presence of other systemic diseases. Urine specimens can be collected by bladder catheterization or suprapubic aspiration of bladder urine, or by having the patient void into a sterile specimen container. Urinalysis is performed to examine6,9,10: • Urine color, appearance, and odor • Specific gravity, osmolarity, or both (concentration of urine ranges from 1.005 to 1.030) • Presence of glucose, ketones, proteins, bilirubin, urobilinogen, occult blood, red blood cells, white blood cells, crystals, casts, bacteria or other microorganisms Urine abnormalities are summarized in Table 9-2. TABLE 9-2 *Ketones are formed from protein and fat metabolism, and trace amounts in the urine are normal. Data from Bates P: Nursing assessment: urinary system. In Lewis SM, Heitkemper MM, Dirksen SR, editors: Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 5, St Louis, 2000, Mosby, pp 1241-1255; Abdomen. In Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE, et al, editors: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 5, St Louis, 2003, Mosby, p 551; Weigel KA, Potter CK: Assessment of the renal system. In Monahan FD, Neighbors M, Sands JK, editors: Phipps’ medical-surgical nursing: health and illness perspectives, ed 8, St Louis, 2008, Mosby, pp 943-960; Pagana KD, Pagana TJ: Mosby’s diagnostic and laboratory test reference, ed 9, St Louis, 2009, Mosby. Two measurements of Cr (end product of muscle metabolism) are performed: measurements of plasma Cr and Cr clearance. Plasma Cr is measured by drawing a sample of venous blood. Increased levels are indicative of decreased renal function. The reference range of plasma Cr is 0.5 to 1.2 mg/dl.10 Cr clearance, also called a 24-hour urine test, specifically measures glomerular filtration rate. Decreased clearance (indicated by elevated levels of plasma creatinine relative to creatinine levels in the urine) indicates decreased renal function. The reference range of Cr clearance is 87 to 139 ml per minute.10 The 24-hour urine collection necessary to measure creatinine clearance has become time consuming and expensive to perform, resulting in a prediction equation for glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). This estimate includes the patient’s age, gender, ethnicity, and serum (blood) creatinine with a reference value of greater than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2.10 As an end product of protein and amino acid metabolism, increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels can be indicative of any of the following: decreased renal function or fluid intake, increased muscle (protein) catabolism, increased protein intake, congestive heart failure, or acute infection. Levels of BUN need to be correlated with plasma Cr levels to implicate renal dysfunction, because BUN level can be affected by decreased fluid intake, increased muscle catabolism, increased protein intake, and acute infection. Alterations in BUN and Cr level can also lead to an alteration in the patient’s mental status. The reference range of BUN is 10 to 20 mg/dl in adults.6,9,10 An x-ray of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (a procedure often abbreviated as “KUB”) is generally performed as an initial screening tool for genitourinary disorders. The size, shape, and position of the renal, ureteral, and bladder structures are delineated to help identify renal calculi (kidney stones), tumor growth or shrinkage (chronic pyelonephritis), and calcifications in the bladder wall. A KUB can also be performed when internal hemorrhage is suspected after major traumatic incidents. Identification of any of these disorders requires further evaluation.6,9,11 Intravenous pyelography consists of (1) taking a baseline radiograph of the genitourinary system, (2) intravenous injection of contrast dye, and (3) sequential radiographs to evaluate the size, shape, and location of urinary tract structures and to evaluate renal excretory function. The location of urinary obstruction or cause of nontraumatic hematuria may be also be identified with this procedure.6,9,11 Retrograde urography consists of passing a catheter or cystoscope into the bladder and then proximally into the ureters before injecting the contrast dye. This procedure is usually performed in conjunction with a cystoscopic examination and is indicated when urinary obstruction or trauma to the genitourinary system is suspected. Evaluation of urethral stent or catheter placement can also be performed with this procedure.5,6,9,11 Renal arteriography consists of injecting radiopaque dye into the renal artery (arteriography) through a catheter that is inserted into the femoral or brachial artery. Arterial blood supply to the kidneys can then be examined radiographically. Indications for arteriography include suspected aneurysm, renal artery stenosis, renovascular hypertension and trauma, palpable renal masses, chronic pyelonephritis, renal abscesses, and determination of the suitability of a (donor) kidney for renal transplantation.9–12 Cystoscopy consists of passing a flexible, fiberoptic scope through the urethra into the bladder to examine the bladder neck, urothelial lining, and ureteral orifices. The patient is generally placed under general or local anesthesia during this procedure. Cystoscopy is performed to directly examine the prostate in men, bladder, urethra, and ureters, as well as to examine the causes of urinary dysfunction and for removal of small tumors.9,10 Cystometry is used to evaluate motor and sensory function of the bladder in patients with incontinence or evidence of neurologic bladder dysfunction. The procedure consists of inserting a catheter into the bladder, followed by saline instillation and pressure measurements of the bladder wall.6,10,11 The structure, function, and perfusion of the kidneys can be examined with a nuclear scan using different radioisotopes for different testing procedures and structures.10 Ultrasound is used to (1) evaluate kidney size, shape, and position; (2) determine the presence of kidney stones, cysts, and prerenal collections of blood, pus, lymph, urine, and solid masses; (3) identify the presence of a dilated collecting system; and (4) help guide needle placement for biopsy or drainage of a renal abscess or for placement of a nephrostomy tube.9 It is the test of choice to help rule out urinary tract obstruction.11 Indications for computed tomography (CT) of the genitourinary system include defining renal parenchyma abnormalities and differentiating solid mass densities as cystic or hemorrhagic. Kidney size and shape, as well as the presence of cysts, abscesses, tumors, calculi, congenital abnormalities, infections, hematomas, and collecting system dilation, can also be assessed with CT.5,9–11 Multiple uses for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and angiography (MRA) include imaging the renal vascular system, staging of renal cell carcinoma, identifying bladder tumors and their local metastases, and distinguishing between benign and malignant prostate tumors.9,10 A renal biopsy consists of examining a small portion of renal tissue that is obtained percutaneously with a needle to determine the pathologic state and diagnosis of a renal disorder, monitor kidney disease progression, evaluate response to medical treatment, and assess for rejection of a renal transplant. A local anesthetic is provided during the procedure, and accuracy of biopsy location is improved when guided by ultrasound, fluoroscope, or CT scanning.6,9–11 Bladder, prostate, and urethral biopsies involve taking tissue specimens from the bladder, prostate, and urethra with a cystoscope, or needle aspiration via the transrectal or transperineal approach. Biopsy of the prostate can also be performed through an open biopsy procedure, which involves incising the perineal area and removing a wedge of prostate tissue. Examination for pain, hematuria, and suspected neoplasm are indications for these biopsies.9 Acute kidney injury (AKI) (formerly known as acute renal failure [ARF]) can result from a variety of causes and is defined as an abrupt or rapid deterioration in renal function that results in a rise in serum creatinine levels or blood urea nitrogen with or without decreased urine output occurring over hours or days.13 There are three types of AKI, categorized by their etiology: prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal.13–15 Prerenal AKI is caused by a decrease in renal blood flow from reduced cardiac output, dehydration, hemorrhage, shock, burns, or trauma.13,14 Intrinsic AKI involves primary damage to kidneys and is caused by acute tubular necrosis (ATN), glomerulonephritis, acute pyelonephritis, atheroembolic renal disease, malignant hypertension, nephrotoxic substances (e.g., aminoglycoside antibiotics or contrast dye), or blood transfusion reactions.13 Postrenal AKI involves obstruction distal to the kidney and can be caused by urinary tract obstruction by renal stones, obstructive tumors, or benign prostatic hypertrophy.13,14,16–19 Two primary classification criteria have been developed to monitor the progression and severity of AKI: Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage Kidney Disease (RIFLE) (Table 9-3) and Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) classification (Table 9-4). TABLE 9-3 Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage Kidney Disease (RIFLE) Classification Data from Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA et al: Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group, Crit Care 8:R204-R212, 2004. TABLE 9-4 Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) Classification Data from Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV et al: Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury, Crit Care 11:R31, 2007. Clinical manifestations of AKI are based upon the specific type and can include the following13–19: • Hypovolemic symptoms of thirst, hypotension, and decreased urine output • Pulmonary vascular congestion, pleural effusion • Cardiomegaly, gallop rhythms, elevated jugular venous pressure Management of AKI includes any of the following: • Treatment of the primary etiology, including antimicrobial agents if applicable • Treatment of life-threatening conditions associated with AKI • Optimize hemodynamics and fluid status • Balance acid-base and electrolytes, particularly potassium levels • Peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement therapy as necessary (refer to the Renal Replacement Therapy section) • Transfusions and blood products Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an irreversible reduction in renal function that occurs as a slow, insidious process from a large number of systemic diseases that injure the kidney or from intrinsic disorders of the kidney. The renal system has considerable functional reserve, and as many as 50% of the nephrons can be destroyed before symptoms occur. Progression of CKD to complete renal failure is termed end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). At this point, renal replacement therapy (RRT) is required for patient survival.14,20 CKD can result from primary renal disease or other systemic diseases. Primary renal diseases that cause CKD are polycystic kidney disease, chronic glomerulonephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, arthroembolic renal disease, and chronic urinary obstruction. The two primary systemic diseases that are associated with CKD are type 2 diabetes and hypertension.21 Other systemic diseases that can result in CKD include gout, systemic lupus erythematosus, amyloidosis, nephrocalcinosis, sickle cell anemia, scleroderma, and human immunodeficiency virus.14 Complications of CKD are similar to those of AKI, including anemia and hypertension, but can also include bone pain and extraosseous calcification.20 Patients with CKD are staged based on the severity of their disease (as measured by GFR), from the United States Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI). Stage 1 is normal kidney function, whereas renal replacement therapy (RRT) is recommended in stage 5.21 Management of CRF includes conservative management or RRT.21,22 Conservative management includes the following16,17,22,23: • Nutritional support, dietary modifications (salt and protein restrictions) • Calcium carbonate and vitamin supplements • Avoiding use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, bisphosphonates, oral estrogens or herbal therapies

Genitourinary System

Preferred Practice Patterns

Body Structure and Function

Clinical Evaluation

Physical Examination

History

Observation

Palpation

Percussion

Auscultation

Diagnostic Tests*

Urinalysis

Creatinine Tests

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

Blood Urea Nitrogen

Radiographic Examination

Kidneys, Ureters, and Bladder X-Ray.

Pyelography.

Renal Arteriography.

Bladder Examination: Cystoscopy

Cystometry (Cystometrogram)

Renal Scanning

Ultrasonography Studies

Computed Tomography Scan

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Angiography

Biopsies

Renal Biopsy.

Bladder, Prostate, and Urethral Biopsies.

Health Conditions

Renal System Dysfunction

Acute Kidney Injury

Class

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) Criteria

Urine Output Criteria

Risk

GFR decrease > 25% or serum creatinine × 1.5

<0.5 ml/kg/hr × 6 hr

Injury

GFR decrease > 50% or serum creatinine × 2

<0.5 ml/kg/hr × 12 hr

Failure

GRF decrease 75% or serum creatinine × 3 or serum creatinine ≥4 mg/dl with an acute rise > 0.5 mg/dl

<0.3 ml/kg × 24 hr or anuria × 12 hr

Loss

Complete loss of kidney function >4 weeks (persistent acute renal failure)

End-stage kidney disease

End-stage kidney disease >3 months

Classes

Serum Creatinine (sCr) Criteria

Urinary Output Criteria

1

sCr increase × 1.5 or sCr increase > 0.3 mg/dl from baseline

<0.5 ml/kg/hr >6 hr

2

sCr increase × 2 from baseline

<0.5 ml/kg/hr > 12 hr

3

sCr increase × 3 or sCr increase > 4 mg/dl with an acute increase > 0.5 mg/dl

<0.5 ml/kg > 24 hr or anuria × 12 hr

Chronic Kidney Disease

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Genitourinary System

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue