Nonoperative Management

The kidney has remarkable healing properties, and nonoperative management has therefore become the treatment of choice for the vast majority of non-life-threatening renal injuries. Nonoperative management results in an excellent long-term outcome in most cases. All grade 1 and 2, and most grade 3 renal injuries can be managed nonoperatively. Exploration of grade 4 and 5 renal injuries often results in nephrectomy; recent data indicates that many of these patients can be managed safely with an expectant approach.

13,

14Patients with suspected penetrating renal injury who are otherwise stable should undergo radiographic staging, whenever possible, to define the injury. Renal gunshot injuries require exploration only if they involve the hilum or are accompanied by signs of continued bleeding, ureteral injuries, or renal pelvis lacerations.

15 Stab wounds and low-velocity gunshot wounds may often be managed conservatively with an acceptably good outcome.

16 Tissue damage from high-velocity gunshot injuries may be more extensive.

The site of penetration by stab wound has an important influence on management—if posterior to the anterior axillary line, most (88%)

17 may be managed nonoperatively.

18,

19 A systematic approach based on clinical, laboratory, and radiologic evaluation may minimize negative exploration after renal stabbing, without increasing morbidity from missed injury. Expectant management of renal stab wounds can be attempted on the hemodynamically stable patient, especially if ureteral and renal pelvis injuries can be ruled out. Ultimately, 98% of blunt renal injuries can be managed nonoperatively.

Grade IV and V injuries more often require surgical exploration, but even many of these can be managed without renal surgery if carefully staged and selected. Patients with high-grade injuries selected for nonoperative management should be closely monitored for persistent bleeding with repeat vital signs and serial hematocrits. If significant urinary extravasation persists beyond 48 hours, prompt urologic consultation with retrograde placement of an internal ureteral “double J” stent (and a urethral catheter to prevent urinary reflux) will often prevent prolonged urinary extravasation and improve perirenal urinoma formation, sepsis, and ileus.

20 Follow-up abdominal CT scans are reserved for high-grade injuries and symptomatic patients only (dropping hematocrit, flank pain, fever, etc.). Should renal bleeding persist, or delayed bleeding occur, angiographic studies with embolization of bleeding vessels will often obviate surgical intervention. It is popularly believed that attempts to repair a bleeding kidney in the days after injury when inflammation is maximal (say 3 to 30 days) will inevitably result in nephrectomy, so it seems prudent to attempt expedient angioembolization if possible.

Angiographic Techniques

Angiography is helpful in defining the exact location and degree of vascular injuries and is useful when planning selective embolization. Arteriography with selective renal embolization for hemorrhage control is a reasonable alternative to laparotomy, provided no other indication for immediate surgery exists.

21 The rate of successful hemostasis by embolization is reportedly identical in blunt and penetrating injuries.

22,

23

Operative Management: Indications

The only absolute indication for renal exploration is life-threatening hemodynamic instability due to renal hemorrhage, irrespective of the mode of injury.

24 Another strong indication for renal exploration is an expanding or pulsatile perirenal hematoma identified at exploratory laparotomy (this finding heralds a grade 5 vascular injury and is quite rare). Relative indications for surgery include suspected renal pelvis injury or persistent bleeding (≥3 units per 24 hours). It has been recognized that most injuries that have urinary extravasation and devitalized kidney fragments heal with nonoperative treatment.

25

Renal Reconstruction

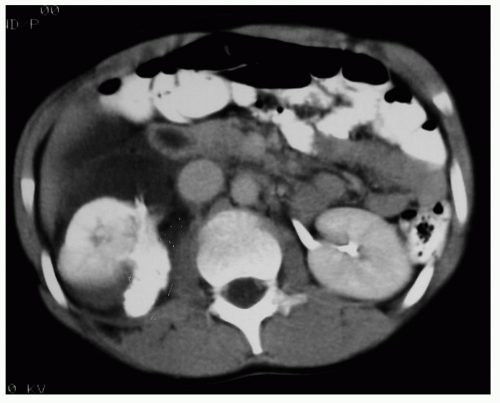

Renal reconstruction (renorrhaphy) by debriding, oversewing, and covering the defect is feasible in most cases (see

Table 2), but partial nephrectomy may be required when large amounts of tissue are damaged, especially at the pole of the kidney. Obtaining early vascular control before opening the Gerota fascia can decrease renal loss caused by bleeding during attempted renal repair (see

Fig. 1).

26 In a series of 133 renal units in which early vessel isolation and control before opening the Gerota fascia was achieved, McAninch et al.

24 reported a very high renal salvage rate of 89%. Early vascular control does not increase postoperative azotemia or mortality.

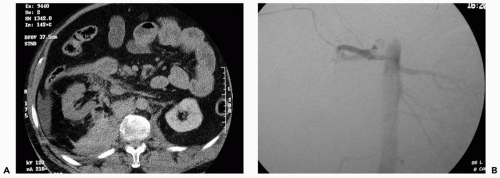

Renovascular Injuries

Renovascular injuries are associated with extensive associated trauma and increased perioperative and postoperative mortality and morbidity. Prompt nephrectomy is usually the treatment of choice except in those very rare cases in which there is a solitary kidney or the patient has sustained bilateral vessel injuries (see

Fig. 2).

17 Attempts at surgical repair of renal artery thrombosis largely fail, and certainly after 8 hours the kidney cannot be salvaged. Many patients with renal vascular injury are critically injured, with numerous associated organ injuries, low body temperature, and poor coagulation; the advisability of major vascular repair over a nephrectomy is limited in the unstable patient if a normal contralateral kidney is present. Damage control with placement of packs and planned return for corrective surgery within 24 hours is another reasonable alternative option.

27 Because the kidney is a paired organ it is sometimes sacrificed with alacrity in patients who would not truly be in danger from an attempted repair. In a recent series of 1,360 adult patients with renal lacerations 23% underwent surgery, and an appalling 64% of these got a nephrectomy.

28 This harmful practice must be avoided.

Complications

Early complications of renal injury include bleeding, infection, perinephric abscess, sepsis, urinary fistula, hypertension, urinary extravasation, and urinoma. Delayed complications include bleeding, hydronephrosis, calculus formation, chronic pyelonephritis, hypertension, arteriovenous fistula, and pseudoaneurysm, although these are all less common. Urinary extravasation can usually be managed expectantly as most resolve spontaneously. In cases where there is persistent leakage with fever and/or sepsis, ureteral stent placement or percutaneous drainage is usually feasible and curative.