Generational conflict and healthcare for older persons

Timothy L. Kauffman and Adrian Schoo

Introduction

The conflict between the older generation and the younger generation is an age-old problem. The issue is particularly poignant in societies and nations that do not venerate their seniors. An important world population demographic was the subject of an editorial in which T.F. Williams, former Director of the National Institute of Ageing in the United States of America, was quoted as saying, ‘Of all human beings who have ever lived on the earth and have reached age 65 years, the majority are alive today’ (Williams, 1987). ‘This statement holds significant implications for the society in general and especially for healthcare providers and their aged patients’ (Kauffman, 1988). By now, everyone has heard the demographic litany about the increasingly aging population and the rising costs of caring for the elderly. The problem that we, as a civilization, face is how to handle this growing dilemma, both fiscally and ethically.

Partisan politics

A member of the US House of Representatives addressed a group of physical therapists at the 1996 Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association. He presented a scenario in which a family had a choice between healthcare for a terminally ill mother or more money for the discretionary use of the younger family members through tax savings derived from reduced healthcare benefits for Medicare patients and pensioners. The Congressman insisted that we must cut the healthcare benefits, even though it is ‘cold hearted’ because we must offer hope and a future (which is being ‘warm-hearted’) to our children and grandchildren. This simplistic either/or verbiage is the source of an increasingly intense generational conflict that pits one generation against another.

These political confrontations persist. The Patient and Affordable Care Act (derisively called Obamacare) became law in the US in 2010 and zero congressional members of one of the political parties voted for the bill. They believe expanding healthcare will add costs to the system and burden employers and younger workers. A major battle was waged during the 2012 US presidential election, with each party accusing the other of cutting Medicare and one party pledged to repeal Obamacare. ‘Medicare, in particular, is the largest driver of future debt’ (GOP, 2012) and the ‘fiscal cliff’ crisis – averted at the last hour of 2012 – would have imposed cuts in Medicare services and to providers.

Demographically, the world’s population has been divided in generational cohorts: traditional (born pre 1946); baby boomers (born 1946–1964); generation X (born 1965–1980); generation Y (born 1981–1995); and 1996 to present are called millennials, which may also include generation Y. Generational conflict pits one age cohort against the other, although this issue is not a requisite of the 21st century. In fact, an aging workforce may be beneficial for individuals, employers and society by integrating them with younger workers (Guest & Shacklock, 2005).

David Willetts, a Conservative Member of Parliament (at the time of this writing) in the United Kingdom published a book entitled the The Pinch: How the Baby Boomers Took Their Children’s Future – And Why They Should Give It Back. He argues that the ‘Boomers’ have accumulated wealth and benefited from the welfare state at the expense of younger generations. As ‘Boomers’ retire, the younger generations will be pinched with higher health and social care costs for their elders while at the same time they did not benefit from low housing costs and good work pensions as the Boomers did (Willetts, 2010).

Dollars, euros, yen and the other monetary units drive this conflict, aided by partisan politics and sensationalism. Political concerns about healthcare costs and wealth distribution are heard around the world, especially in countries with aging populations. This is part of the demographic that is manipulated in the conflict of ‘us against them’, especially because older people use more healthcare and social security/pensioner dollars/euros. Also the eurozone crisis stemming from increasing government debts in Greece, France, Ireland, Spain and Portugal has fanned the flames of generational conflict. Böcking (2012) wrote, ‘older people are living at the expense of the young, and it’s high time the next generation took to the streets to confront their parents’.

Global demographics

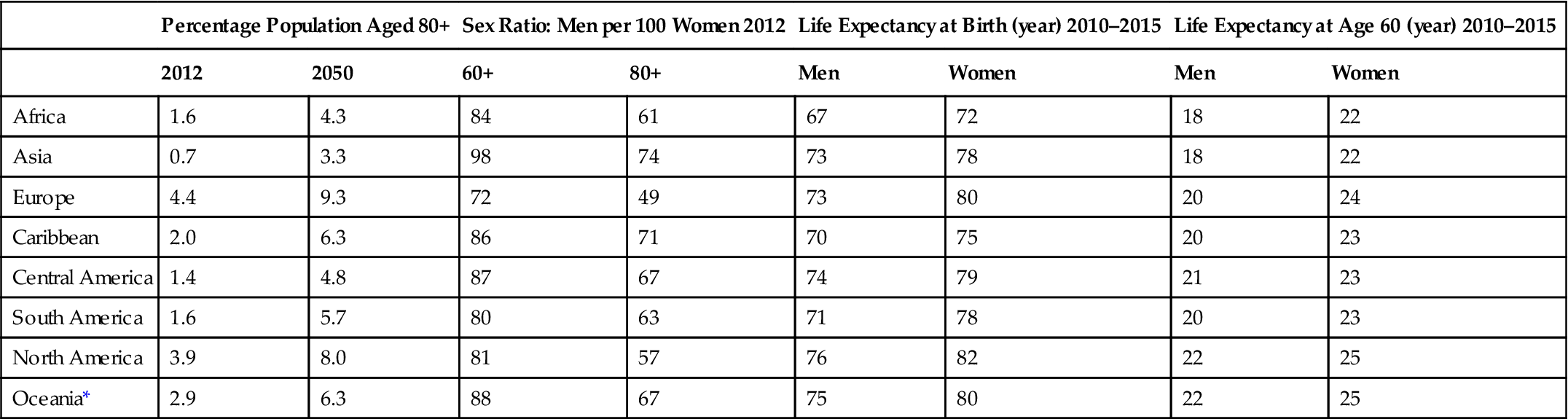

The world has known many ages, like the Stone Age or the Bronze Age, but today we are embarking on the ‘Age of Age’, which brings many positives but also, significant challenges for individuals, families, agencies, cultures and governments. According to the World Health Organization, every second of time, 2 persons somewhere on earth will celebrate a 60th birthday, which amounts to 58 million new 60-year-old persons yearly. It is estimated that persons 60 years old or older account for 11.5% of the world’s population and this will increase to 21.8% by 2050. The number of people living into the ninth decade of life will increase nearly 300% between 2012 and 2050. Life expectancy at birth is over 80 years in 30 countries, an increase from 19 countries only 5 years ago. Based on multiple sources, projections for percent of population aged 80, sex ratios, life expectancy at birth and at age 60 are shown in Table 76.1 (UNFPA and HelpAge, 2012).

Table 76.1

Worldwide aging and life expectancy

| Percentage Population Aged 80+ | Sex Ratio: Men per 100 Women 2012 | Life Expectancy at Birth (year) 2010–2015 | Life Expectancy at Age 60 (year) 2010–2015 | |||||

| 2012 | 2050 | 60+ | 80+ | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Africa | 1.6 | 4.3 | 84 | 61 | 67 | 72 | 18 | 22 |

| Asia | 0.7 | 3.3 | 98 | 74 | 73 | 78 | 18 | 22 |

| Europe | 4.4 | 9.3 | 72 | 49 | 73 | 80 | 20 | 24 |

| Caribbean | 2.0 | 6.3 | 86 | 71 | 70 | 75 | 20 | 23 |

| Central America | 1.4 | 4.8 | 87 | 67 | 74 | 79 | 21 | 23 |

| South America | 1.6 | 5.7 | 80 | 63 | 71 | 78 | 20 | 23 |

| North America | 3.9 | 8.0 | 81 | 57 | 76 | 82 | 22 | 25 |

| Oceania* | 2.9 | 6.3 | 88 | 67 | 75 | 80 | 22 | 25 |

Europe was the first region in the world in which the demographic transformation resulting from increased life expectancy was manifested. It has the highest proportion of old people in the world. Of 35 European countries in 2010, Germany has the highest population aged over 64 years (20.7%), followed by Italy (20.2%), Greece (18.9%) and Sweden (18.1%) (eurostat, 2010). In Australia the median age was estimated to be 36.6 years in 2005 and is predicted to reach 43.6 in 2050, and the percentage of people over 65 years of age from 12.3% in 2000 to 23.9% in 2050 (Guest & Shacklock, 2005). Japan has the world’s oldest population, with 31.6% of people being over the age of 59 years. In 2011 there were 316 600 centenarians and this is projected to explode to 3.2 million by 2050. In juxtaposition to life expectancy is life span, that is, the maximum number of years a member of a species has lived. In 1798 the oldest human in recorded data was 103, and in 1898 it was 110 years. The record increased in 1990 to 115 and later to 122.45 years in 1997 (UNFPA and HelpAge, 2012).

A key factor in increased life expectancy is that fertility has decreased worldwide from 5 children per woman in 1950–55 to 2.5 children in 2010–15 (UNFPA and HelpAge, 2012). The fertility rate (children per woman) in Japan dropped from 2.13 in 1970 to 1.37 in 2009; with sustainability or replacement rate being 2.1 children per woman (Er, 2010). Germany has the highest percentage of aging population in Europe but the number of persons living there despite immigration has decreased from 82.4 million in 2003 to 82 million in 2008. The fertility rate is 1.4 children per woman (Karsch & Hossmann, 2010). This demographic is not often presented in the popular press or in political rhetoric that adds to the generational conflict.

These demographics portend dire challenges to societies and governments as the trends, if continued, suggest that most persons born since 2000 will live to age 100 years or more (Christiansen et al., 2009). But not all aging researchers agree with this demographic. From a biological perspective, Carnes et al. (2013) argue that the genetics of persons born today are not much changed from our prehistoric ancestors. At that time deaths resulted from acute diseases and the harshness of hunting and gathering. Today’s demographics are due to changes in civilization such as healthcare delaying mortality and conveniences like grocery stores obviating the need to hunt wild animals. The catabolic effects of aging can be delayed but not stopped because there is no biological dictate that humans live beyond the age of grandparent caregivers. The genetics of aging are too complex to establish a single or several genome manipulations to allow most persons to reach 100 years of age. Predictions are important but can be wrong; only time will tell.

Healthcare for older persons

In light of the demographics, how will governments be able to continue the old age pension and healthcare programs for younger generations? Financial security is important for governments and those who are governed. It is notable that in 2011–12, 33% of persons aged 60 years and above were employed worldwide yet 47% had ‘cash worries’, including health costs. Internationally, 44% of persons 60 years and older rated their health status as ‘fair’ and 22% were ‘bad or very bad’ and rising healthcare and medication costs are a source of stress and anxiety (UNFPA and HelpAge, 2012). Retirement income and health status are related and used to promote generational conflict; however, the purpose in this chapter is not to expound on social security or pension plans, but instead on how people can access healthcare.

Many of the world’s countries provide universal healthcare through taxation and most also allow for private insurance, which shortens waiting lists for care. Most of the countries have seen the costs go up partially due to the aging demographics shown above. In the United Kingdom, total government healthcare costs increased from 58.26 billion pounds in 2001–2 to 109.43 billion pounds in 2008–9. The National Health Service (NHS) has a core principle ‘to provide a universal service for all based on clinical need, not on ability to pay’ (Boyle, 2011). In collaboration, the European Union Insurance Card allows all cardholders access to state-provided healthcare when travelling in any of the 27 members of the European Union. The card is free and the cost for care is aligned with the costs in home countries, which is free in some.

Brazil, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Australia and New Zealand have similar systems which are working well but also face the demography of aging. In Japan, long-term care costs are expected to increase from 1.4% of gross domestic product in 2006 to 4% in 2050 (Colombo et al., 2011). A trend in Japan, as in many countries, is to provide more care at home rather than in hospitals or long-term care facilities (UNFPA and HelpAge, 2012).

United states of america and medicare

In the US, the rehabilitation of geriatric patients takes place largely within the Medicare and Medicaid programs, which are nearly universal socialized medical systems. As the population ages, the systems have become an increasingly partisan political battleground, with a moderate to high level of distrust, frustration and confusion among the various players on the field, including the beneficiaries and their advocates, lobbyists and families; the care providers, both individuals and institutions; the insurance companies; and the politicians and regulatory bureaucrats.

There is some justification for this sociopolitical quagmire because the Medicare and Medicaid (low-income seniors and run by state governments) systems are large, changing and expensive. In 2012 over 50.7 million people were covered by the Medicare system, costing $574.2 billion in benefits. Government income for the year was $536.9 billion. The Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance, HI) Trust Fund was enhanced by the Affordable Care Act innovations but is projected to be exhausted by 2026 if no changes are made. Medicare Part B for outpatient services ‘is adequately funded for the next 10 years’ but average annual costs have increased 6.1% for the past 5 years. Total Medicare expenditures for 2012 amounted to 3.6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The average benefit cost in 2012 per enrollee was $5227 Part A and $5097 Part B (Trustees, 2013).

Medicare Parts A and B: the confusion

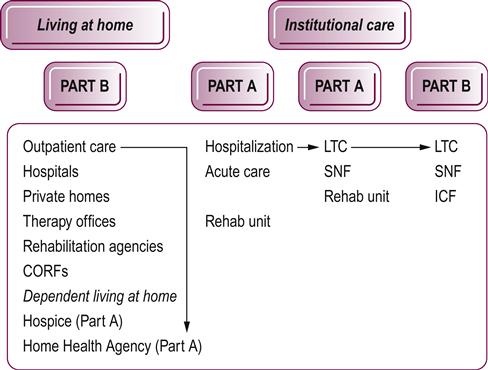

As stated above, Medicare Part A is a hospital insurance; however, services under the HI trust fund may be rendered in a hospital, rehabilitation unit, hospice system, skilled nursing facility or home healthcare situation. In contrast, coverage under Medicare Part B may take place in an outpatient setting in the hospital, a patient’s home, an extended care facility, a skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation agency, comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facility (CORF) or other outpatient treatment center. Thus, the strict nomenclature of inpatient versus outpatient care is not fully appropriate. This continuum of healthcare under the Medicare system is shown in Figure 76.1. From the rehabilitation perspective, there should be no difference in the sophistication of the level of care rendered to a patient, whether it falls under Part A or Part B. The differentiation arises only from the sociomedical factors that necessitate inpatient rather than outpatient care.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree