THE NATURE OF WORRY

Worrying is both a normal phenomenon and an activity which occurs in association with a wide range of emotional disorders. The worries of GAD patients closely resemble in content the worries of non-patients. Craske, Rapee, Jackel and Barlow (1989) demonstrated that normal and GAD worries differed little in terms of their content, but GAD patients rated their worries as less controllable and less successfully reduced by corrective attempts compared with the worries of non-patients.

It may be useful to distinguish between different types of thought which may interact in significant ways in the development and maintenance of emotional dysfunction (Wells, 1994a, 1995). Worry appears to differ in form from negative automatic thoughts, and from obsessions (Wells, 1994a; Wells & Morrison, 1994). Borkovec, Robinson, Pruzinski and De Pree (1983a) define worry as a ‘chain of thoughts and images, negatively affect-laden and relatively uncontrollable’ (p. 10). Worry has been viewed as a problem-solving activity (e.g Borkovec et al., 1983a; Davey, 1994), and it is typically a more conceptual-verbal activity than an imaginal one (Borkovec & Inz, 1990; Wells & Morrison, 1994).

The nature of worry in GAD

Patients with GAD report periods of chronic and repeated worrying on a variety of topics. The experience of worrying can range from a pervasive ‘feeling’ of being worried or, more typically in GAD, to discrete episodes of rumination lasting from minutes to hours. Worry is experienced as distressing and relatively uncontrollable, although people with GAD often report that the activity can be interrupted by distracting events. While worrying may be initiated by an involuntary intruding thought, it can also be initiated in a deliberate way. Wells (1994a) suggests that it is useful to distinguish the initiation of worry from its maintenance. While initiation may be relatively involuntary, continued worrying is amenable to conscious control. Wells (1994a) proposes that since GAD worries and normal worries differ little in content but differ more in their appraised uncontrollability, a model of abnormal worry in GAD should take account of patients’ appraisal of the activity of worrying. This is a central feature of the cognitive model and treatment of GAD advanced by Wells (1994a, 1995) which is the focus of the remainder of this chapter.

A COGNITIVE MODEL OF GAD

It follows that if the content of normal and GAD worries is similar, a main distinguishing feature of GAD is the form that worry takes and the subjects’ appraisal of the significance of worrying. On the basis of this assertion, Wells (1994a, 1995) distinguishes between two types of worry termed Type 1 and Type 2 worries. Type 1 worries concern external daily events such as the welfare of a partner, and non-cognitive internal events such as concerns about bodily sensations. Type 2 worries in contrast are focused on the nature and occurrence of thoughts themselves—for example, worrying that worry will lead to insanity. Type 2 worry is basically worry about worry. The cognitive model of GAD asserts that abnormal varieties of worry such as that found in GAD are associated with a high incidence of Type 2 worries, in which GAD patients negatively appraise the activity of worrying. Negative appraisals or Type 2 worries reflect negative beliefs that patients hold about worrying: Examples are:

- My worries are uncontrollable.

- Worrying is harmful.

- I could go crazy with worrying.

- I could enter a state of worry and never get out.

- My worries will take over and control me.

Aside from negative beliefs the model asserts that GAD patients also have tacit positive beliefs about worrying, or the benefits of rumination as a coping strategy. Once worry has been triggered, for example, the person with GAD may feel compelled to reason-out the worry in order to find a solution or to prevent catastrophe. Similarly, there may be a specific belief that it is important to worry in order to maintain an acceptable degree of subjective safety. The use of worry as a safety strategy is illustrated by a patient who constantly worried about being mugged when walking alone in the street because he believed that worrying offered a means of ‘always being prepared’ to deal with such a problem. Unfortunately his preoccupation with being mugged and how he could deal with it heightened his sense of vulnerability as he generated an increasing range of negative scenarios. It is unlikely that repeated worrying actually increases safety; a preoccupation with worrying thoughts in a situation may distract from actual vigilance for threat. Examples of positive worry beliefs are:

- Worrying helps me cope. (‘If I worry about the worst and I can see myself coping then I probably will cope if it happens.’)

- If I worry I can prevent bad things from happening.

- Worrying helps me solve problems.

- I wouldn’t do anything if I didn’t worry.

- If I worry I can always be prepared.

Unfortunately the use of worry as a coping or processing strategy generates its own problems. Worrying increases sensitivity to threat-related information, and generates an elaborated range of possible negative outcomes and scenarios each of which is capable of sustaining a worry in its own right. Thus, the magnitude and breadth of worrying is liable to increase. Furthermore, the initial belief that worry is intended to challenge (e.g. I can’t cope) remains unchanged in the long term because new negative scenarios which could provide evidence of not coping are likely to be generated during the course of the worry episode.

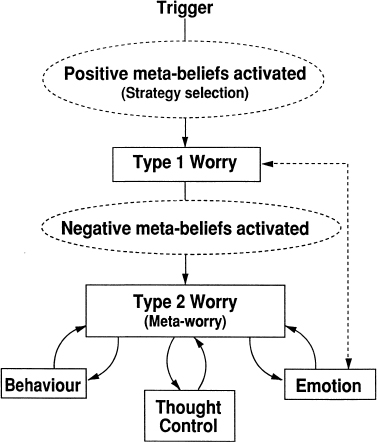

According to this model the development of GAD can be seen over a time course. Many patients report that they have a long history of worrying. It appears that some people initially used worry in order to deal with real or imagined problems in life. This strategy may have evolved from the influence of a parent who modelled the use of worry as a means of dealing with problems, or from the reinforcement of the ‘benefits’ or worrying. At some point, however, worrying becomes the focus of negative appraisal. This may result from new information such as a parent experiencing mental health problems associated with worrying, or worry may be negatively appraised because practise of the activity has led to a degree of automatisation of worry triggers to the extent that it has become an increasingly disruptive influence in the person’s life. Once worry about worry has been established a number of additional factors are involved in the escalation and maintenance of the problem: (1) behavioural responses; (2) thought control attempts; (3) emotional symptoms. This cognitive model of GAD is presented in Figure 8.0.

Figure 8.0 A cognitive model of GAD (Wells, 1995)

Figure 8.0 offers a schematic of the cognitive model that can be used for constructing idiosyncratic case formulations. In this model, the GAD patient uses worry as a processing strategy in response to a trigger. Triggers for Type 1 worrying vary, such as exposure to negative news material, an intruding thought such as an unpleasant image, exposure to a situation associated with a sense of subjective danger. The selection of worry (or rumination) as a coping strategy stems from the activation of tacit positive beliefs about the use of worry. Once the person with GAD is executing a worry routine, negative beliefs about worrying are activated. With repeated experience negative beliefs may be readily activated by the early signs of worrying, such as the initial intruding thought. Negative beliefs concern the uncontrollability, and dangers associated with worrying, and stimulate negative appraisal of worry (meta-worry). The negative appraisal of worry motivates the use of strategies intended to reduce the appraised danger. These strategies will now be considered in turn:

Behavioural responses

Two types of behaviour are important: Avoidance, and reassurance seeking. The Type 1 and Type 2 worry distinction has implications for the way avoidance in GAD is conceptualised. What is it that GAD patients are avoiding? On one level GAD is associated with avoidance of a range of situations. There may be avoidance of social events, avoidance of unpleasant news items, or more pervasive avoidance resembling agoraphobia. Avoidance may be of external dangers (linked to Type 1 worry) believed to be inherent in a situation, such as the possibility of drawing attention to the self and humiliation. However, avoidance is also of the dangers of worrying itself (linked to Type 2 worry). The meta-cognitive model emphasises the importance of avoidance as a means of preventing worry and the dangers associated with it as well as a means of avoiding external threat. In summary, avoidance may therefore be linked to Type 1 and Type 2 worries and the beliefs from which they stem. Detailed analysis is required to determine the cognitions which motivate specific avoidance responses. Clearly, optimal cognitive modification procedures are those which manipulate key belief-linked behaviours. In the following example Type 1 and Type 2 worries and associated behaviours are evident:

Example: M was a 28-year-old engineer presenting with a four-year history of panic attacks and chronic worries. He met diagnostic criteria for panic disorder and GAD. His panic problem responded well to cognitive therapy and he became panic free following six sessions. The remaining five treatment sessions focused primarily on his remaining worry problem. He reported chronic worry about many life circumstances, such as failing to reach high standards of achievement at work, worries about contracting food-poisoning, and concerns that his partner could be involved in accidents. One of his central goals in treatment was to be able to worry less. He realised that his worries were unrealistic but believed that they were uncontrollable. As a result he attempted to avoid worrying by restricting his work, by carefully examining jars and tins of food in the supermarket to ensure that they were undamaged and sealed adequately, and by arriving home at the end of the day after his partner in case she may be late to return and this would lead to worrying.

In this example Type 1 worries are clearly evident and they concern:

Type 2 worries concern the uncontrollability of worry. It became clear during treatment that the patient reported arriving home after his partner in order to prevent worrying about her. This avoidance was clearly linked to Type 2 concerns since it was aimed at avoiding worry itself as opposed to some external danger. It also emerged that his avoidance of damaged food containers was primarily a means of preventing worry. When the patient was asked how likely it was that he thought he would contract food-poisoning from damaged containers he disclosed that he thought it was unlikely, but if he ate something from such a container he would not be able to stop worrying about it.

Other examples of overt avoidance serving to avoid the dangers of worry, rather than other danger, include avoidance of news items, television programmes, or uncertainty in order to avoid worrying.

Reassurance seeking is also evident in some cases of GAD. Reassurance seeking is aimed at interrupting worry cycles or preventing the onset of chronic worry. Unfortunately it can be a counter-productive strategy for worry control, since it may lead to increased ambiguity concerning Type 1 threat. For example, reassurance seeking can lead to conflicting responses across respondents which increases the range of stimuli that are worried about. In other situations, reassurance, such as having a partner telephone at regular intervals to say that he/she is safe, can temporarily prevent worry but this increases the propensity for worry if reassurance is not delivered on time. In other words, the search for reassurance can generate greater uncertainty, and a greater need to worry in order to plan coping options.

Thought control

The use of thought control in GAD manifests in different ways. Since people with GAD have positive as well as negative beliefs about their worries, worry may be practised within strict limits or in special ways that are intended to exploit the benefits of worrying while, at the same time, avoiding the dangers. Thus worrying becomes a controlled rumination strategy used as a means of generating and rehearsing coping responses. In contrast, strategies may be used to suppress worries. Attempts not to worry are motivated by negative appraisal of the consequences of continued worrying. While the execution of Type 1 worry may be controlled in ways to meet personal goals, a disadvantage of suppression control attempts is that they may inadvertently increase the occurrence of unwanted thoughts, as demonstrated experimentally (e.g. Wegner, Schneider, Carter & White, 1987; Clark, Ball & Pape, 1991). The effect of thought control or suppression attempts may be to increase the frequency of worry triggers, an outcome likely to strengthen negative beliefs about thoughts such as beliefs about their uncontrollability. A different perspective on thought control is presented by the concept that worry itself may serve a cognitive avoidance function. That is, some individuals may use worry or rumination to block-out other types of more distressing thought (e.g. Borkovec & Inz, 1990). According to this view, worry represents a form of cognitive-emotional avoidance. The use of worry to distract from more upsetting thoughts could lead to a failure to emotionally process and deal with more upsetting issues. Thoughts about such issues may continue to intrude as a sign of failure to emotionally process (Borkovec & Inz, 1990; Wells, 1995; Wells & Papageorgiou, 1995), and thereby strengthen meta-worries and negative beliefs.

Some patients report the use of distraction to avoid worries. This may take several forms such as absorption with work or hobbies. The distracting activity may then become a discriminative stimulus for worrying. The problem with attempts to suppress or distract from worry is that such attempts can prevent disconfirmation of negative beliefs about worry since it terminates exposure to the activity.

Thought control strategies in GAD are analogues to the concept of safety behaviours. Moreover, Type 1 worrying may itself be a safety behaviour to the extent that it is used to prevent appraised catastrophe. More specifically, it is a safety behaviour when it is used to generate and rehearse strategies for coping with future threats. Suppression strategies or attempts to control one’s worries are safety behaviours intended to avert the appraised dangers of worrying, and are thus associated with Type 2 worries.

Emotion

Type 1 and Type 2 worrying are associated with emotional responses. Type 1 worry can lead to initial increments in anxiety and tension, or decrements in anxiety if the goals of worrying are being met. However, with the activation of Type 2 worrying, anxiety escalates and emotional symptoms may be interpreted as evidence supporting Type 2 concerns. For example, symptoms of a racing mind, dissociation, and inability to relax may be viewed as evidence of loss of mental control. In some instances, where there are appraisals of immediate mental catastrophe, panic attacks may result. The model can account for the overlap between GAD and panic in this way.

ELICITING INFORMATION FOR CONCEPTUALISATION

In some cases of GAD Type 2 worries (also termed meta-worries; Wells, 1994a) are highly apparent whilst in other cases they are less obvious. Since conceptualisation, socialisation, and treatment rely on the elicitation of Type 2 worry (meta-worry), the therapist should be skilled in the use of strategies for eliciting this material. Before considering in detail the process of building an idiosyncratic model, the next part of this chapter reviews verbal strategies for determining the nature and relevance of Type 2 worry (metaworry).

Verbal strategies for eliciting Type 2 worry

A range of strategies are available for eliciting Type 2 worry (meta-worry), these are: guided questioning; the advantages-disadvantages analysis; identifying control behaviours; experimental strategies; questionnaires.

Guided questioning

One of the principal aims in the assessment and the socialisation process is the exploration of the role of appraisal of the worry process as a central determinant of problem level. Some examples of key questions for determining the content of meta-worry are as follows:

- What is it that bothers you most about worrying?

- As worrying is distressing for you, why don’t you stop worrying?

- Could anything bad happen if you let yourself worry?

- How much control do you have over worry?

- What would it mean if you couldn’t control worry?

- Could anything bad happen if you gave up worrying?

- Do you think it’s normal to have worrying thoughts?

- What’s the worst that could happen if you didn’t try to control a bad worry episode?

In discussing the nature of the patient’s problem the therapist should be sensitive to patient statements such as: ‘The problem is I worry too much’, ‘I have periods when I worry about everything’, ‘I don’t seem to be able to stop worrying’, ‘I worry all the time’.

These general statements about the process of worrying offer a pathway for accessing more specific Type 2 worries and concerns (note: these statements are manifestations of appraisal of worry itself, i.e. Type 2 worry). When these responses are encountered the therapist should determine the implications of worrying, determine the worst that can happen, and question why the patient doesn’t stop worrying (this question can elicit appraisals of uncontrollability). Some examples follow.

Example 1

Example 2

Advantages–disadvantages analysis

Use of the advantages–disadvantages strategy to elicit meta-worry consists of asking patients to consider, and list the advantages of worrying, and then list the disadvantages. The advantages given for worrying provide information relating to positive beliefs associated with sustained rumination/worrying. The disadvantages analysis provides a means of assessing the content of meta-worry and associated negative beliefs. In particular, the therapist looks for negative beliefs that relate to the dangers of worrying, and appraisals of uncontrollability. An advantages–disadvantages analysis of a 41-year-old male GAD patient who presented with a 12-year history of worry about illness/accidents, and social incompetence is presented in Table 8.0.

Identifying control behaviours

The existence of thought control behaviours is a marker for appraisals concerning the negative consequences of worrying. The function of control behaviours should be questioned to elicit meta-worry. The following dialogue illustrates the identification of control behaviours and elicitation of their idiosyncratic function:

Table 8.0 Results of an advantages–disadvantages worry analysis

| Advantages of worrying | Disadvantages of worrying |

| I won’t become complacent | It makes me anxious |

| I’ll be less likely to offend people | It stops me concentrating |

| I’ll be prepared to deal with problems | I can’t enjoy things |

| It helps me keep a check on my health | It’s harmful |

| It prevents me doing what I want to do | |

| It’s uncontrollable |

In this example, detailed examination of the use of worry-control behaviours was used to prime information concerning the dangers of not using control. Here, control behaviours used by the patient consisted of telling himself not to worry, and self-reassurance by analysing the risks in the situation. Metaworry focused on worry being uncontrollable, and worry leading to loss of mental functioning. The control behaviours were seen as preventing these negative events.

A similar analysis of avoidance and the aims of avoidance can be undertaken to determine meta-worry concerns. In this situation the consequences of not avoiding stimuli/situations should be questioned.

Experimental strategies

When meta-worries and beliefs concern themes of loss of control, mental illness, and abnormality, individuals with GAD are often uncomfortable about disclosing this material. In some cases there is a fear that the therapist will confirm that particular presenting symptoms are a sign of mental illness or abnormality, and so these themes are avoided. In other cases these fears are readily accessible to the patient when in the worried/ruminatory mode, but are less apparent and tangible when not in this mode. During the course of treatment behavioural experiments in which the patient is encouraged to dwell on worry topics and engage in worry episodes can provide a means of determining meta-worries. However, worry induction tends to subjectively differ from ‘naturally occurring’ worry episodes. Nevertheless, discussion of the nature of this contrast can yield useful information.

Questionnaire assessment

Self-report instruments for assessing dimensions of worry (including Type 2 worry) and beliefs about worry were reviewed in Chapter 2. The Anxious Thoughts Inventory (AnTI: Wells, 1994b) is particularly useful in the present context, since this measure of worry proneness has three subscales that assess Type 1 and Type 2 worry separately (see Chapter 2). The Meta-Cognitions Questionnaire (MCQ: Cartwright-Hatton & Wells, 1997) offers a measure of positive and negative beliefs about worry. Both measures are reproduced in the Appendix.

Generalised anxiety disorder scale (GADS)

The GADS (reproduced at the back of this book) is a multi-component rating scale for measuring distress, positive and negative beliefs, behaviours, and control strategies considered important in the maintenance of GAD as predicted by Wells’s (1995) cognitive model.

Thought control questionnaire (TCQ)

The TCQ, developed by Wells and Davies (1994), is a 30-item instrument which assesses five empirically distinct types of strategies used to control unpleasant and/or unwanted thoughts: (1) distraction (e.g. ‘I do something that I enjoy’); (2) social control (e.g. ‘I ask my friends if they have similar thoughts’); (3) worry (e.g. ‘I focus on different negative thoughts’); (4) punishment (e.g. ‘I punish myself for thinking the thought’); and (5) reappraisal (e.g. ‘I try to reinterpret the thought’). The questionnaire was initially devised as a research instrument but is useful for eliciting control behaviours and for measuring the extent of thought control attempts as a treatment outcome measure.

Two more general measures of worry that may be considered—although they do not provide separate information on meta-worry are the Penn-State Worry Questionnaire and the Worry Domains Questionnaire.

Penn-State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ)

The PSWQ is a 16-item questionnaire developed by Meyer, Miller, Metzger and Borkovec (1990) to evaluate an individual’s tendency to worry in general, not related to specific worry topics. The items reflect a tendency to worry excessively and chronically. For example: ‘I worry all the time’; ‘Many situations make me worry’; ‘Once I start worrying I cannot stop’. Responses are requested on a 5-point rating scale ranging from ‘not at all typical’ to ‘very typical’. The scale shows good psychometric properties and initial data suggests that it is responsive to treatment effects (see review by Molina & Borkovec, 1994; Borkovec & Costello, 1993).

Worry domains questionnaire (WDQ)

The WDQ was developed by Tallis, Eysenck and Mathews (1992), as a content measure of worry. Twenty-five items are used to tap five domains of worry: worry about relationships (e.g. ‘that I will lose close friends’); lack of confidence (e.g. ‘that I lack confidence’); aimless future (e.g. ‘that I’ll never achieve my ambitions’); work (e.g. ‘that I don’t work hard enough’); and financial (e.g. ‘that I am not able to afford things’). Respondents are asked to indicate how much they worry about each of the items and make their responses on a scale of: ‘not at all, a little, moderately, quite a bit, and extremely’. Total score provides a measure of frequency of worry, while individual items can be examined to determine the content of most salient concerns. For further information the reader should refer to Tallis, Davey and Bond (1994).

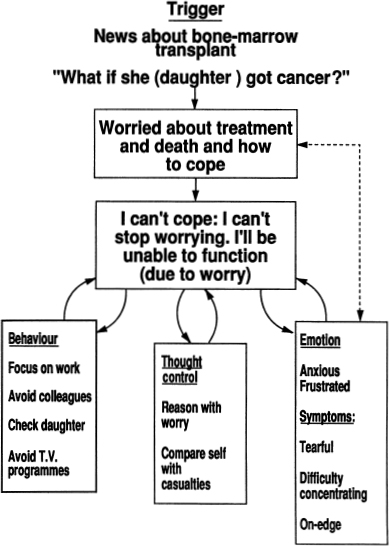

FROM COGNITIVE MODEL TO CASE CONCEPTUALISATION

To construct a GAD conceptualisation a recent and specific problematic worry episode should be reviewed and the data needed to construct the model elicited. Several episodes may be sampled in a similar way to buildup the full range of data for an overall conceptualisation. The model is necessarily somewhat complex because it includes two types of worry and belief, and feedback loops among them. However, it is simplified in practice by prioritising parts of the model. More specifically, the lower half of the model incorporating negative interpretation of worry (meta-worry) and resulting behaviours and affect should be formulated first. This serves in simplifying the model for socialisation. Later treatment sessions focus on eliciting the role of positive beliefs and the problems associated with the use of worry as a coping strategy.

Figure 8.1 A cross-sectional idiosyncratic GAD case conceptualisation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree