1 General Information

Fractures Overview

Bone fractures occur when there is a break in the continuity and integrity of the bone as a result of excessive force. Fractures usually begin with intense pain and swelling at the site of injury, along with some degree of loss of function. Furthermore, fractures can also present with shock and fever, as seen in severe cases. Characteristics of fractures include deformities, abnormal movement, bony crepitus, and a perception of friction between the fracture fragments. Fractures that result in a deformed limb and severe pain often require immediate surgical intervention. In severe fractures, the circulation may become disrupted and lead to a loss of pulse distal to the fracture site. Fractures involving articulation sites may result in subsequent dysfunction of the joint.

Fractures can be classified into different categories based on the impact of the fracture. For example, they can be classified as open or closed, depending on the integrity of the skin tissue and mucosa; as complete or incomplete, depending on the severity of the fracture; or as stable or unstable in terms of displacement, angulation, and shortening. Fractures can also be described as traumatic or nontraumatic, the latter being more commonly seen as a pathologic fracture. Traumatic fractures are seen more frequently in clinical practice than nontraumatic fractures.

Radiographic examination should include anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the fractured bone, along with the nearest joint. Some fractures require additional radiographic views, such as AP and oblique views for the metacarpus and metatarsus, lateral and axial views for the calcaneus, and AP and ulnar deviations for the scaphoid. Sometimes, if the injury is difficult to determine, comparison views of the contralateral uninvolved side will be helpful in reaching an accurate diagnosis. In cases with a clinically suspected fracture and negative or inconclusive findings on initial radiography, a radiographic examination should be repeated 2 weeks later, when the fracture line will emerge as healed fragments, as seen in carpal scaphoid fractures. For fractures adjacent to a joint or a complex anatomic structure, X-ray examination provides limited information; computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is therefore highly recommended to provide a clear depiction of the fracture.

The overall principles of fracture management are: restoration of anatomy, stable fracture fixation, and early mobilization of the limb and patient. Fracture reduction is a procedure to restore anatomy by positioning the displaced bone fragments in the correct alignment, and to encourage healing and normal use of the bone and limb. Fixation is an attempt to maintain proper alignment of the fracture site until the bone becomes strong enough to support the union. Functional exercise must be started as soon as possible, to restore the functional ability of the muscle, tendon, and joint ligaments without compromising the fixation hardware.

Fracture Classification

To understand the injury mechanism, select proper treatment options, and compare the outcomes of different treatment regimes, it is important to have a system of fracture classification. Numerous fracture-classification systems have been proposed in orthopedics. A standardized and widely accepted fracture-classification system would facilitate communication between physicians and assist documentation and research. For clinical relevance, it should reflect the complexity of treatment planning and have prognostic value for patient outcome. Maurice E. Müller indicated that a classification is useful only if it considers the severity of the bone lesion and serves as a basis for treatment and for evaluation of results. The AO classification system is currently in use along with conventional classification. The latest version of the Müller AO classification was published in 1996 in the form of a supplement to volume 10 of The Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, where the classifications for the long bones, spine, and pelvis were comprehensive; however, smaller bones such as those of the hand and foot were only listed with numbers to indicate their location. The Müller AO classification has become widely accepted and applied in practice not only because of the great impact the AO Foundation has had over the years in the field of orthopedics, but also because of scientific validation of the classification system itself. The strength of Müller’s system is that it provides a framework within which a surgeon can recognize, identify, and describe long bone injuries. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) has established its own classification system, with the AO system as a reference. Essentially, the OTA system added to the AO system by classifying those bones that were never classified in the AO system; this ultimately led to the formation of the AO/OTA system. The OTA published the latest version of fracture classification in December 2007 in a supplement to volume 21 of the Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. The OTA adopted the AO system of classifying the long bones, spine, and pelvis, and significantly revised the classification for the clavicle and scapula, foot and hand, and patella. In the current chapter, we will introduce the AO system in detail, while the OTA system will be described in later chapters that deal with the clavicle, scapula, foot, hand, and patella.

The AO Foundation should be mentioned whenever the AO fracture classification system is discussed. In 1958, a group of Swiss general and orthopedic surgeons led by Maurice E. Müller, Martin Allgower, and Hans Willenegger established the AO Foundation. The AO “pioneers” proposed a method of absolute stability through compression between fracture fragments to achieve a goal of rigid internal fixation of fractures. This concept may be less than perfect by modern standards, but caused a revolution in the treatment of fractures. The most important contribution of the AO Foundation is to promote these original principles, which not only are of great practical and scientific value but can also be continually refined and improved with use. Over the past 10 years, the AO principles of fracture management have evolved in various ways, and have begun to advance methods of internal fixation. Today, 50 years after its establishment, the AO principle for operative fracture fixation and the bone-healing concept are accepted worldwide. As research in the biomechanics of fractures has advanced, the AO principles and the hardware for internal fixation have seen dramatic improvement, with emphasis shifting from strong internal fixation based on pure mechanics to fixation based on biomechanics. The latest AO principles stress the patho-physiology and biology of the bone-healing process rather than its mechanics.

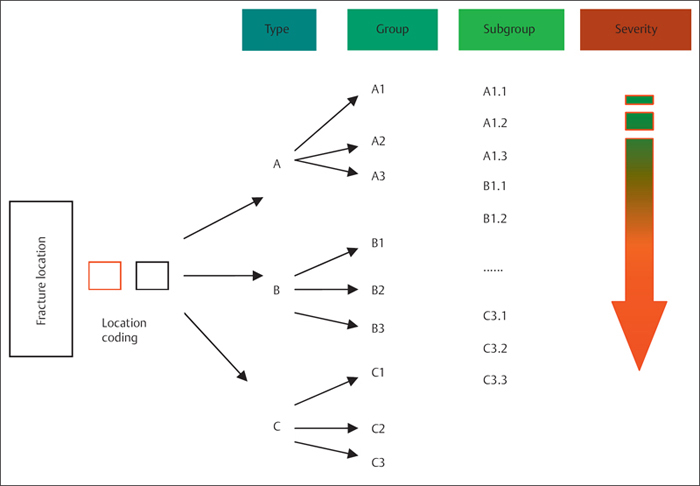

The AO classification system adopted a five-element alphanumeric code to describe each fracture as the following:  . The first two elements of alphanumeric code describe the location (bone segment), followed by an alphabetic character for the fracture type (A, B, C), and lastly two numbers for morphologic characteristics of the fracture (group and subgroup). This is shown in Fig. 1.1.

. The first two elements of alphanumeric code describe the location (bone segment), followed by an alphabetic character for the fracture type (A, B, C), and lastly two numbers for morphologic characteristics of the fracture (group and subgroup). This is shown in Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 AO classification of fractures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree