General Features of Osteoarthritis

What are the clinical features of osteoarthritis?

The clinical features of osteoarthritis relate to both symptoms and signs. As has been discussed in Chapter 1, the principle symptom of osteoarthritis is pain. Typically this occurs during movement and/or loading of the joint. It may vary greatly in severity from mild to very severe. Indeed, as already discussed, structural change may be entirely asymptomatic. Usually pain from osteoarthritis changes only slowly and undergoes variation with ‘good weeks’ and ‘bad weeks’. Some authors consider that osteoarthritis undergoes ‘flares’ with temporary marked increases in pain and swelling, although the mechanism underlying this is unclear.

Nocturnal pain may be a prominent feature. Although taken as a late, poor prognostic feature by some, it may be present early in the clinical course, and possibly may be particularly helped by NSAIDs. The mechanism in this situation is thought to be vascular in nature with increased intraosseous pressure. As was discussed earlier, this can be associated with localized areas of avascular necrosis and more rapid deterioration in joint architecture with more rapid clinical progression.

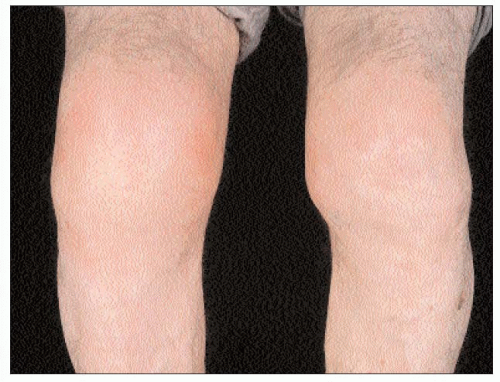

Osteophyte growth and bony remodelling can result in altered joint shape and, at superficial sites, this can readily be observed clinically (2.1). Similarly, loss of bone stock, often as a result of avascular necrosis, may result in malalignment with resultant varus, valgus, flexion, or other deformities (2.2). Again these deformities can be readily observed, and may be a risk factor for future progression and deterioration.

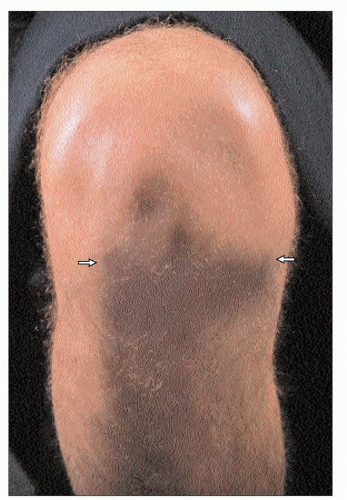

2.1 Femoral osteophyte is visible and palpable in this flexed knee as prominent bony ridging (arrows) along the anterior border of each condyle giving an inverted ‘V’ appearance. |

Swelling that is due to soft-tissue rather than bony enlargement may be observed. Although synovial thickening may be a factor, it is more commonly due to increased synovial fluid and distension of the joint capsule. Joint swellings due to fluid tend to occur in natural weak areas of the capsule, and thus in characteristic locations. Acute swellings may sometimes occur in a fashion similar to that seen in the ‘flares’ of pain. The mechanism is again unclear, although in some cases a crystal synovitis may occur, most commonly related to calcium pyrophosphate crystals (‘pseudogout’) (2.3).

In association with crystal synovitis, an overlying erythema may occur, but in general cutaneous features including local heat are unusual.

Stiffness in osteoarthritis is usually relatively short-lived and often more related to inactivity, such as sitting, rather than being the more typical and very prolonged early morning stiffness seen in, for example, rheumatoid arthritis.

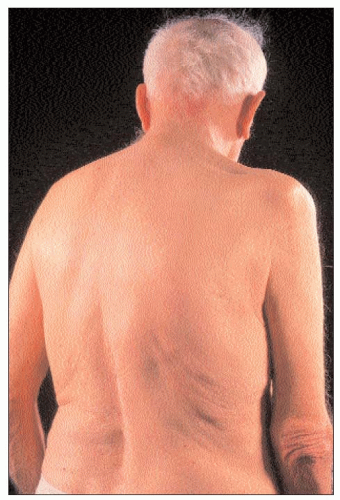

Muscle wasting may be a prominent feature of osteoarthritis. Although general immobility may produce generalized wasting, the most marked wasting is seen in the muscles that act across the affected joint. Location will determine whether this is readily appreciated with some joint involvement: the hip and hand, for example, less likely to produce obvious atrophy than others, such as the knee and shoulder (2.4). Although atrophy may be hard to appreciate, the consequence of this may be more easily observed in terms of reduced strength and function. Associated proprioceptive impairment can also result in functional impairment with, for example, impaired gait and balance.

2.4 Global wasting of muscles — especially visible for deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor — in association with right glenohumeral osteoarthritis. |

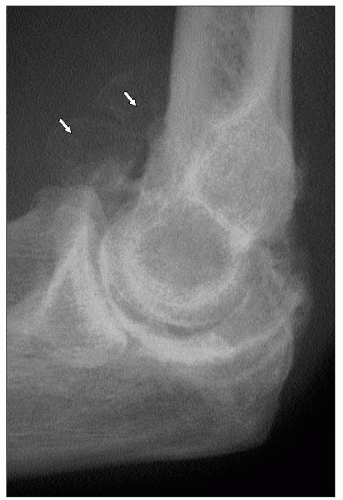

Ligamentous involvement and joint space loss may result in instability and further functional impairment which may manifest as a lack of confidence, falling, and fear of falling. Associated meniscal damage and intra-articular ‘loosebodies’ may result in symptoms of ‘locking’, especially at the knee and elbow (2.5) and of ‘giving way’ (mainly at the knee). Locking is a temporary, painful inability to move the joint in one plane, usually extension, and this often lasts a matter of minutes. It is a mechanical problem that results from an interpolation of tissue between the articular surfaces and, if recurrent, may require surgical removal.

‘Giving way’ is a more difficult concept and has been considered variously as a feeling of instability and lack of confidence in a limb, usually the leg, to a more transient, sudden weakness in the muscles causing a partial but not complete loss of ability to weight-bear, lasting for just a fraction of a second.

Systemic upset is not a feature of osteoarthritis since it is a non-inflammatory condition that does not trigger the acute phase response. An exception is those patients who experience associated calcium crystal synovitis. In this situation, the marked release of inflammatory mediators may result not only in local pain and inflammation, but also fever, myalgia, sweating, and confusion.

What are the radiological features of osteoarthritis?

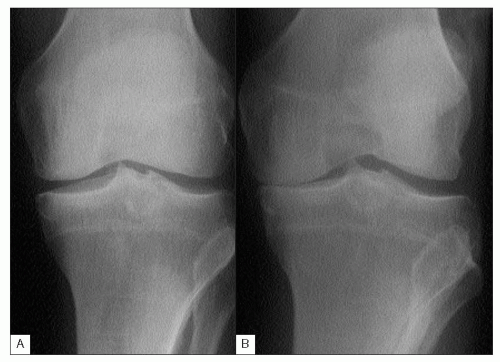

Joint space narrowing can be appreciated by looking at the intercortical distance between bone separated by hyaline cartilage. The situation is more complex in those joints that contain a fibrocartilage meniscus, such as the tibiofemoral joints of the knee. In this situation, meniscal damage, or indeed surgical removal, will result in a reduced joint space without this necessarily reflecting hyaline cartilage loss. Conversely, at certain sites, such as the knee, a normal joint space width does not exclude significant cartilage loss. This can arise if a non-weight-bearing view is taken (2.6) or if the knee is fully extended — a semi-flexed weight-bearing view is optimal and more sensitive at detecting focal cartilage loss. Similarly, the alignment of the x-ray beam relative to the joint may also make a major difference to the appreciation of joint space loss (2.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree