General Considerations

Peter F. M. Choong

Complex reconstructive surgery is now commonplace for the knee as limb sparing surgery replaces amputation as the preferred technique for managing malignancies of the knee (1,2). Many of these techniques are also being extended to nonmalignant conditions (1,3,4,5,6,7) where significant bone loss and instability are dominant features such as with marked condylar bone defects associated with multiple revisions of a knee joint replacement or significant loss of bone integrity associated with periprosthetic fractures and also malunited or ununited fractures around the knee. The primary aim of reconstructive surgery is to achieve a stable mobile joint.

INDICATIONS

Primary Malignancies

The knee is the commonest site for the development of osteosarcoma. Over the last two decades, there has been a shift in surgical philosophy from amputation to limb sparing surgery (2,8). Much of this shift has been attributed to advances in imaging, chemotherapy, prostheses, and surgical techniques. Moreover, it has been shown that function is superior with limb salvage surgery (9) while patient survival is not affected by limb sparing surgery and the risk of local recurrence after limb sparing surgery is extremely low (10). A number of studies have also indicated the cost effectiveness of limb sparing surgery as compared to amputation (11,12).

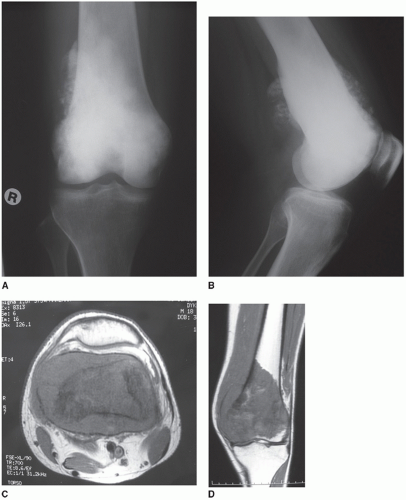

Most osteosarcomas develop in the metaphysis of the femur (Fig. 14.1A,B). These tumors are often associated with a large soft tissue component that grows through the cortical bone of the metaphysis and extends proximally and distally from the metaphysis through the intramedullary bone (Fig. 14.1C,D). When developing in the immature skeleton, a metaphyseal osteosarcoma often meets resistance at the growth plate. Penetration of this structure is often a late event and may be regarded as a suitable margin if there is nonconclusive evidence of growth plate invasion (13). Invasion of the synovium in the supracondylar region is uncommon, and imaging frequently shows the pushing rather than the invasive characteristic of osteosarcoma as it

abuts the synovium. Invasion of the knee joint proper is also an uncommon occurrence (13) but may arise in the presence of pathologic fracture, cruciate ligament invasion, poor biopsy technique, and capsular invasion at the collateral ligaments. The surgical management of distal femoral osteosarcomas will depend on whether there is tumor within the joint or not. If there has been no breach of the joint capsule, then an intra-articular resection of the distal femur is preferred. A more complex extra-articular resection is indicated if invasion of the joint has occurred.

abuts the synovium. Invasion of the knee joint proper is also an uncommon occurrence (13) but may arise in the presence of pathologic fracture, cruciate ligament invasion, poor biopsy technique, and capsular invasion at the collateral ligaments. The surgical management of distal femoral osteosarcomas will depend on whether there is tumor within the joint or not. If there has been no breach of the joint capsule, then an intra-articular resection of the distal femur is preferred. A more complex extra-articular resection is indicated if invasion of the joint has occurred.

The size, shape, and direction of protrusion of the extraosseous soft tissue component will determine the nature of the soft tissue dissection, the structures that can be preserved, and those that will require sacrifice. The confluence of neurovascular structures in the popliteal fossa makes planning of surgical margins critical in the presence of a large posteriorly directed soft tissue component.

Metastatic Malignancies

The commonest malignant tumor of bone is a metastasis from carcinoma. Although the femur is a common site for metastasis, distal femoral metastases are less common than proximal femoral metastases. Metastases are usually from breast, lung, thyroid, kidney, and prostate primary tumors. Gastrointestinal tract tumors uncommonly target bone. Condylar metastases are easily treated by resection and megaprosthetic reconstruction (14,15). Extraosseous soft tissue components are uncommon except for renal metastases, and consequently, sacrifice of soft tissue attachments can be avoided and bone margins need not be extensive.

Isolated lesions are uncommon but may occur in relation to thyroid and renal metastases. Occasionally, late presentation of breast carcinoma metastases many years after the treatment of the primary may present as a solitary lesion. In all these cases, en bloc resection may be attempted with locally curative intent. More often, however, disease arises in multiple sites within a single bone and progression of disease is to be expected. In planning surgical management, protection of the whole bone should be sought in anticipation of further development of disease. Long stemmed cemented intramedullary fixation is preferred as a method for protecting the femoral diaphysis.

Nonneoplastic Conditions

Multiple revisions of joint replacement may lead to significant loss of distal femoral bone stock causing elevation of the joint line, loss of condylar offset, and disappearance of the epicondyles. Under such circumstances, reconstruction with standard prostheses or even those that include prosthetic augments or posterior stabilized designs may not be sufficient to provide adequate collateral stability or return a stable kinematic range of flexion and extension. Megaprosthestic reconstruction with a rotating hinge mechanism provides a unique opportunity for correcting the bone loss and instability in a single device (3,4,5,7).

Poorly united or nonunion of supracondylar or condylar fractures can provide complex challenges for reconstruction (Fig. 14.2A,B). Frequently, patients present with the late effects of their malunited or ununited fractures such as gross coronal plane malalignment, loss of range of motion, and pain of degenerative disease. In contrast to failed revision joint replacement, abnormalities of union are more frequently associated with fixed deformities and contractures. Surgical solutions to this include combinations of resection of sufficient bone and prosthetic implantation to allow correction of the deformity and soft tissue releases to correct the restriction of movement (Fig. 14.2C,D). Correction of chronic deformity always carries the risk of nerve and vascular injury.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO LIMB SPARING SURGERY

Infection

Infection may not only threaten the success of knee surgery, but may also lead to amputation if it becomes uncontrolled. Major reconstructive surgery must not be undertaken in the setting of infection unless it is being performed as part of a staged approach to the management of acute/chronically infected joint prostheses.

Skeletally Immature Patients

Mobile reconstruction following resection of osteosarcoma of the distal femur in patients with open growth plates may lead to the development of significant limb length inequality. Predicted inequality may be reduced by surgically restricting growth in the contralateral limb by epiphysiodesis. However, the potential for ongoing growth in the contralateral limb may be so great that interrupting this may result in unacceptable stunting of overall height. In principle, the younger the patient, the greater is the potential for limb length discrepancy. If the anticipated inequality is substantial, then reconstruction is contraindicated and amputation should be considered. Matching leg lengths through modification of amputation limb prostheses may be easier to achieve

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree