Gastroenterology

David L. Brown

Chris G. Pappas

Courtney A. Dawley

INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

From a gastrointestinal (GI) perspective, long-distance runners have been the most scrutinized group, but recent studies have looked at the GI symptoms of long-distance walkers, cyclists, triathletes, and weightlifters. Upper and lower GI tract symptoms occur with equal prevalence in cyclists. Lower GI symptoms predominate nearly 2 to 1 over upper GI symptoms in endurance runners. Whether running or riding, these same patterns also hold true in triathletes (24). In low-intensity long-distance walking, the overall occurrence of GI symptoms is much lower than in other sports studied. The most common symptoms are flatulence and nausea, which occur at similar rates to those of the baseline population (only 5% of walkers) (25).

Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux is extremely common in athletes. Cyclists have the lowest esophageal acid exposure, followed closely by runners. Weightlifters have the highest rates of reflux. All groups have increased reflux when exercising postprandially. Cyclists have a modest increase in reflux after eating, whereas weightlifters nearly double and runners triple their reflux (8).

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is associated with the primary risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. H. pylori is associated with 65%-95% of gastric ulcers and 75% of duodenal ulcers. The estimated risk of a clinically significant NSAID-induced event, including bleeding and perforation, is 1%-4% per year for nonselective NSAID. Either of these factors alone increases ulcer risk 20-fold. When both risk factors are present, an individual is 61 times more likely to develop ulcer disease (31).

The primary lower GI condition of athletes is runner’s diarrhea, affecting up to 26% of marathon runners (14). Runner’s diarrhea is not typically associated with bleeding; however, studies in marathon runners showed that 20% of runners completing a marathon had occult blood in their stools, another 6% had bloody diarrhea, and 17% had frank hematochezia while in training (20).

UPPER GI DISEASES

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

The most common presenting complaints for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are heartburn and acid regurgitation. The classic presentation is retrosternal burning, exacerbated by meals, intense workouts, and recumbency, with resolution on antacids. Symptoms are typically more common during initial training periods with improvement as the athlete becomes more conditioned (22). Atypical symptoms include nausea, excessive salivation (water brash), bloating, and belching (27). Extraintestinal complaints include sore throat, exertional dyspnea, cough, or wheezing (Table 37.1).

GERD pathophysiology involves retrograde movement of gastric acid and the proteolytic enzyme pepsin, which causes irritation of the esophageal epithelium. Reflux alone is insufficient to explain why individuals become symptomatic because affected patients have reflux rates similar to healthy individuals (11). The critical factor in symptom development appears to be that the contact time between refluxed material and the epithelium is so excessive that the normal gastric contents overwhelm the epithelial protective mechanisms. Alternatively, symptoms may develop when normal contact time occurs in the face of insufficient protective mechanisms.

Symptomatic reflux episodes during exercise are likely multifactorial but correlate best with transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs). This vagally mediated reflex facilitates lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation and gas venting in response to gaseous stomach distention. The decrease in LES tone and reflux associated with TLESRs last longer and are not accompanied by a swallow-induced peristaltic sweep, leading to prolonged acid exposure. Supine or forward-flexed posture during particular modes of exercise increases intra-abdominal pressure, overcoming the mechanical protection of the LES and negating bolus acid clearance achieved by gravity. Increasing exercise intensity is associated with increased reflux episodes and duration of acid exposure (28).

As exercise intensity increases, the frequency, duration, and amplitude of esophageal contractions progressively decrease. High-intensity exercise also reduces splanchnic blood flow, which may inhibit restoration of acid-base balance and deprive the epithelium of the oxygen and nutrients needed for damage repair.

Table 37.1 GERD Symptom Patterns

Classic Symptoms

Atypical Symptoms/Signs

Red Flag Symptoms

Heartburn

Pulmonary

Chronic untreated symptoms

Acid regurgitation

Asthma

Dysphagia

Nonspecific Symptoms

Chronic cough

Weight loss

Nausea

ENT

Hematemesis

Dyspepsia

Dental erosions

Melena

Bloating

Halitosis

Odynophagia

Belching

Lingual sensitivity

Vomiting

Indigestion

Chronic pharyngitis

Early satiety

Hypersalivation/water brash

Hoarseness

Rhinitis/sinusitis

Globus

Cardiac

Atypical chest pain

ENT, ear, nose, and throat; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

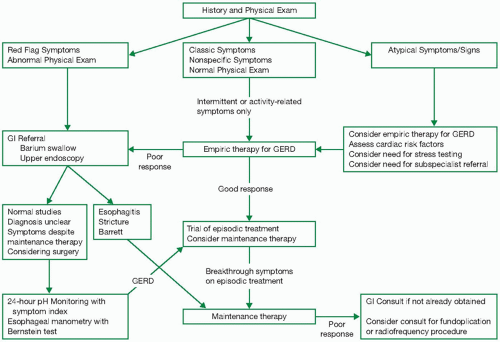

If the history and physical raise red flags, symptoms are particularly severe, or the diagnosis is unclear, the athlete should be referred for gastroenterology evaluation (Fig. 37.1). In patients with extraintestinal manifestations or atypical GERD symptoms, providers can consider an initial therapeutic trial. If empiric therapy fails, it is important not only to consult gastroenterology, but also the specialty that would evaluate for extraintestinal complications (Fig. 37.2).

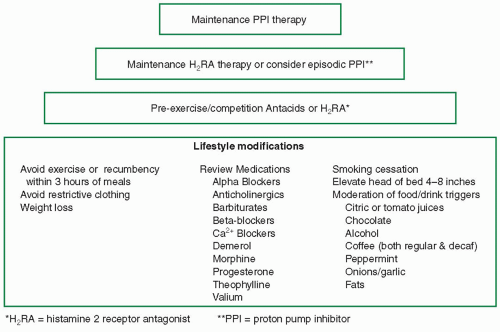

Behavioral and training interventions may improve symptoms such as decreasing the intensity of training briefly, then gradually increasing intensity as tolerated. Other interventions include avoiding postprandial exercise or waiting to exercise for at least 3 hours after a meal. Avoiding high-calorie meals and fatty foods prior to exercise may also help symptoms (22).

Persistent symptoms despite behavioral interventions warrant medical therapy. Episodic complaints are treated with over-the-counter (OTC) antacids, as needed, or antireflux medication, such as histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or standard-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (22). This can be advanced to prescription-strength antireflux (H2RA or PPI) therapy if control is insufficient. Should symptoms continue after 6 weeks of H2RA therapy, neither continuing therapy nor increasing the dose is likely to achieve control (13). It was previously common practice to consider add-on therapy to prescription-dose H2RA with a prokinetic agent to improve LES tone, gastric emptying, and peristalsis. These agents all have side effects that make them undesirable for use in athletes. Bethanechol has generalized cholinergic effects. Metoclopramide has a high incidence of fatigue, restlessness, tremor, and tardive dyskinesia, making it a poor choice for anything more than sporadic use. Cisapride, formerly the prokinetic agent of choice, was found to be associated with arrhythmia development, especially with concomitant use of macrolides, imidazoles, or protease inhibitors (34). This discovery led to severe prescribing restrictions in the United States.

In individuals who fail to respond to H2RAs, PPIs are the treatment of choice. PPIs provide more rapid relief of symptoms (2) and are more likely than H2RAs to heal and prevent recurrence of erosive esophagitis (7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree