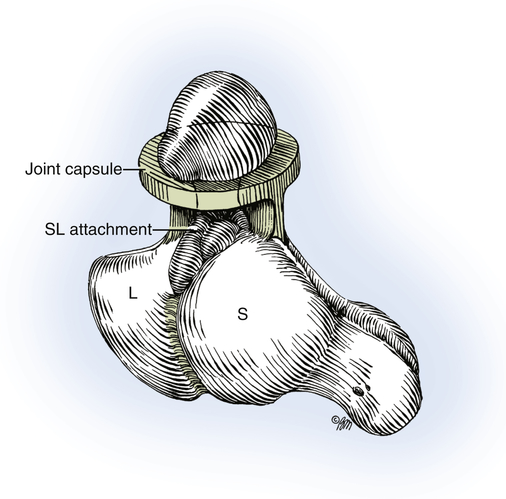

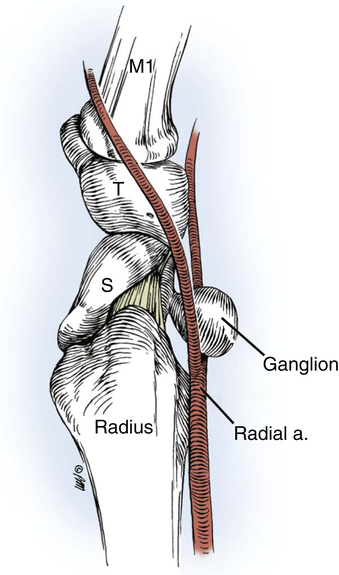

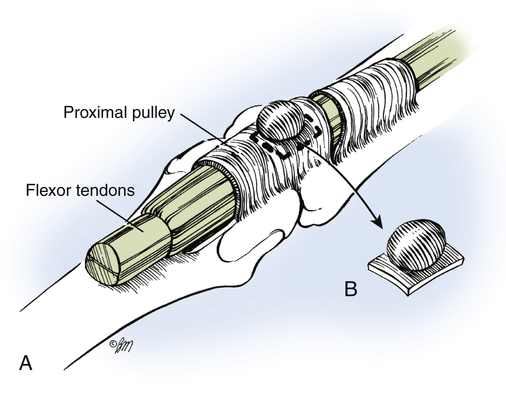

Tumors of the forearm and hand can arise from any tissue in the upper extremity including synovium, fat, skin, lymphatics, nerves, blood vessels, or bone. Tumors are classified into three categories: tumor mimicking lesions, benign tumors, and malignant tumors.1 A therapist is likely to see these clients on their caseload because of the prevalence with which these clients come to our referring physicians. For this reason, it is important to know the common sequence of diagnosis and treatment, to have an appreciation for the tissues involved, and to know how to manage both the physical care and psychological implications of an upper extremity tumor. Ganglion cysts are the most common tumors, accounting for 15% to 60% of all cases of the hand and wrist.1 The presentation and diagnosis can be confusing, and treatment is variable. A thorough medical history of related trauma or repetitive use of the extremity and reports of rapid changes in growth and pain are vital for providing appropriate client care. Although malignancy is unlikely, significant changes in growth, size, and appearance warrant prompt referral to the primary care provider or surgeon. A ganglion is a mucin-filled soft tissue cyst, formed from the synovial lining of a joint or tendon sheath.2 Theories on formation of ganglions include mucoid degeneration, synovial herniation, and trauma to the joint capsule or ligaments.2 Ganglions are generally painless. They tend to fluctuate in size with time and activity, and they may or may not resolve without intervention. Ganglions can appear gradually over time, or suddenly. They usually occur singly and in very specific locations, but they have been reported from almost every joint in the wrist and hand.2 If enlarged, the ganglion can produce pain secondary to pressure on the nearby tissues and structures. Clients tend to report pain in positions of extreme wrist flexion, extension, or with weight bearing activities through the wrist.1 The posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) in the dorsal wrist capsule, the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel, and the ulnar nerve within Guyon’s canal at the wrist have all been known to be symptomatic when there is a ganglion within these structures.2 Usually, ganglion cysts arise from the scapholunate joint and ligament in the wrist. The main cyst is connected by a mucin-filled cleft interconnecting the cyst to the underlying joint (Fig. 36-1).2 Ganglions can occur at any age in either gender, and they can resolve spontaneously or require therapeutic or surgical intervention. Ganglions occur more frequently in women, between the teenage years through middle adulthood. They are found more often in clients with ligamentous laxity. A recent history of trauma or injury is present in 10% of cases, or there may be a history of repetitive use of the hand or extremity.2 Ganglions have been diagnosed in children, but spontaneous healing almost always occurs within 2 years of diagnosis. A pediatric client is seldom a surgical candidate for ganglion excision.1 Dorsal wrist ganglions are the most common, comprising 60% to 70% of all hand and wrist ganglions.2 They are seen over the dorsum of the wrist, usually between the extensor pollicus longus and extensor digitorum communis, at the level of the scapholunate ligament. Volar wrist ganglions are the second most common type of ganglions, comprising 15% to 20% of cases. They are usually associated with the underlying scapholunate ligament and less often over the scaphotrapezial joint. A volar wrist ganglion is commonly seen on the radial aspect of the wrist (over the flexor carpi radialis tendon) (Fig. 36-2). When evaluating a volar wrist ganglion, the therapist should palpate the cyst, and perform an Allen’s vascular test (described in Chapter 5 ). A mass that is pulsatile in nature or obstructs blood flow to the hand is indicative of a vascular tumor, but it can easily be misidentified as a volar wrist ganglion because of the proximity to the radial artery and the scapholunate joint (Fig. 36-3). Retinacular cysts are a type of ganglion that develops from a tendon sheath, rather than a joint. A volar retinacular ganglion is palpable and symptomatic near the proximal inter phalangeal (PIP) joint or the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint. An extensor retinacular ganglion is uncommon but, if detected, usually involves the first extensor compartment (abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis) and can be associated with de Quervain tenosynovitis (inflammation of the synovial lining surrounding the extensors within the first dorsal compartment). Retinacular cysts form on the tendon sheath itself, not the tendon within (Fig. 36-4). Hidden or occult ganglions can be a source of unexplained wrist pain and disproportionate tenderness.2 Due to the deep location in the wrist, this type of ganglion is a common source of pressure on the PIN within the dorsal capsule, causing dorsal wrist pain.2 The ganglion may be detected by placing the client’s wrist in marked volar flexion.2 An intraosseus ganglion is rare and usually is detected with involvement of the scaphoid or lunate. computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated for these clients, who have ongoing wrist pain of unclear etiology and without a visible cyst. Mucous cysts are a type of ganglion that is seen on the dorsal joints of the digits, most often the base of the middle phalanx and/or the distal phalanx (Fig. 36-5). There is close association between mucous cysts and osteoarthritis of the DIP and PIP joints.2 The mucous cyst typically forms over an osteophyte on the DIP joint known as a Heberden’s node. Longitudinal grooving of the nail secondary to pressure on the nail matrix may be seen with this.2 A carpal boss is an osteoarthritic spur that forms over the carpal metacarpal joint of either the index or long fingers where the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis insert. A carpal boss is firm, non-mobile, tender to palpation, and can be observed with the wrist placed in flexion. Clients seek a physician because they are worried about potential malignancy, impaired function, weakness, or pain.2 The course of treatment is dependent on the approach that the client and surgeon agree upon. Indications for treatment of ganglia include pain, interference with activity, nerve compression, and ulceration of overlying skin.3 Watchful waiting is indicated for clients who do not have persistent pain or limitation of function.2 The surgeon may also choose to aspirate the cyst with or without a corticosteroid. Studies have shown 60% recurrence of ganglions with this approach, although resolution can occur with repeated aspiration.1 Surgical resection is the most effective treatment, classically used after exhausting nonsurgical options.4 The ganglion is excised, and a portion of the attached joint capsule is removed to prevent ganglion recurrence while protecting ligaments for carpal stability. If the tumor is solid or diagnosis is questionable, an open excision allows for biopsy of the tumor to assist with plans for further interventions. A client who chooses to have an operative mucous cyst excision usually does so for aesthetic reasons, pain, or ulceration of the overlying skin. It is important for the underlying osteophyte to be excised to avoid recurrence.1 Occasionally the excisional aspect of the mucous cyst and underlying osteophyte requires a skin graft or flap.5 1. Symptom management: Allowing tissue support with the use of a resting orthotic 2. Gentle home exercise programs (HEPs): Aimed at maintaining range of motion (ROM) and function 3. Instruction in heat and cold modalities as well as contraindications and precautions of both: For example, the client should not use heat if pain and swelling have increased; in this case, a cold pack would be appropriate for acute symptoms

Ganglions and Tumors of the Hand and Wrist

Ganglion Cysts

Diagnosis and Epidemiology

Demographics

Anatomic Sites

Timelines and Healing

Non-Operative Treatment

Operative Treatment

Timeline for Therapy

Non-Operative