15 Fu’s subcutaneous needling

Concept and terminology

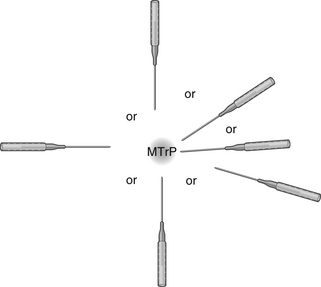

Fu’s subcutaneous needling (FSN) is a therapeutic approach for musculoskeletal painful disorders that originated from traditional acupuncture. This procedure is performed by inserting a special trocar needle into the subcutaneous layer around the afflicted spot to achieve the desired effect (Figure 15.1).

The name FSN, or Fu Zhen (

, in simplified Chinese;

, in simplified Chinese;

, in Traditional Chinese), has some profound implications. ‘Fu Zhen’ is the Chinese pronunciation for FSN. Fu is the surname of the inventor, who is also the first author of this chapter. In Chinese, ‘Fu,

, in Traditional Chinese), has some profound implications. ‘Fu Zhen’ is the Chinese pronunciation for FSN. Fu is the surname of the inventor, who is also the first author of this chapter. In Chinese, ‘Fu,  ’ means floating, and it could also mean superficial. ‘Zhen’ means acupuncture or needling. Therefore, in some English-language papers, FSN is also called Floating Acupuncture (Huang et al. 1998), Fu’s Acupuncture (Zhang 2004), Fu Needling (Xia & Huang 2004) and Floating Needling (Fu & Huang 1999). However, neither floating nor superficial are precise translations; the word subcutaneous is a better substitute in terms of demonstrating the manipulation features of FSN.

’ means floating, and it could also mean superficial. ‘Zhen’ means acupuncture or needling. Therefore, in some English-language papers, FSN is also called Floating Acupuncture (Huang et al. 1998), Fu’s Acupuncture (Zhang 2004), Fu Needling (Xia & Huang 2004) and Floating Needling (Fu & Huang 1999). However, neither floating nor superficial are precise translations; the word subcutaneous is a better substitute in terms of demonstrating the manipulation features of FSN.

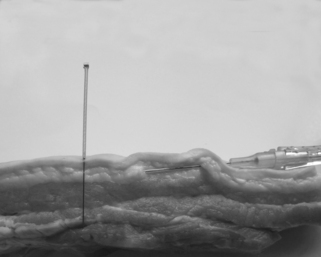

Although FSN originated from classic acupuncture, FSN’s manipulation and theory have nothing to do with the concepts of traditional acupuncture, such as meridians, acupoints, Yin-Yang, and Qi. Therefore, FSN is not some variety of acupuncture and should not be referred to as acupuncture. Figure 15.2 shows the FSN needle in a subcutaneous layer of a human cadaver.

Another approach, called intradermal needle therapy, is easily confused with FSN. The intradermal needle (Figure 15.3) is a type of short needle made of stainless steel wire, especially used for embedding in the skin (Cheng 1987) rather than in the subcutaneous layer.

The term ‘Fu’s subcutaneous needling’ was first mentioned in a 2005 article by Fu and Xu, in which they described the treatment method (Fu & Xu 2005), followed by several other research papers (Fu et al. 2006; Fu et al. 2007). FSN should be clearly distinguished dry needling, which involves the insertion of a fine single-use sterile needle into a trigger point (TrP) for the treatment of myofascial pain. Dry needling has been in use since the 1970s and differs from the use of needling from an Oriental paradigm (Baldry 1995, 2000, 2002, Chu 1995, Hsieh et al. 2007, Hong 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, Simons 2004, 2008). TrP dry needling is based on a Western anatomical and neurophysiological paradigm and has been increasingly utilized in the Western world, especially in the US, UK, The Netherlands, Canada, Belgium, Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Ireland, Brazil, South Africa and Spain, among others (Dommerholt 2006). Unlike traditional acupuncture, dry needling does not consider ancient Chinese philosophy and traditional ideas. Traditional acupuncture is based on pre-scientific ideas, such as meridians, Qi (a kind of invisible energy) and Yin-Yang (Ellis et al. 1991, White & Ernst 2001, Kim 2004), whereas dry needling is entirely based on the recent understanding of scientific neurophysiology, anatomy, and pain sciences (Ghia et al. 1976, Melzack et al. 1977, Melzack 1981). The manipulation method used in acupuncture differs from that used in dry needling and is based on different theoretical foundations and principles.

Contemporary research and the emergence of dry needling have reduced the sense of mystique surrounding non-injection therapies for pain (Amaro 2008). Although acupuncture and dry needling have different theoretical bases, they are similar in some aspects:

1. Nothing is injected into the body;

2. Needles may target the same points known as either a trigger point in dry needling or an Ah-shi point in Chinese medicine; and

Further, in trigger point dry needling the importance of the local twitch response is emphasized, which is a reaction during needling with some resemblance to the ‘De-Qi’ effect in acupuncture (Hong 1994). Chou et al. (2008, 2009) have modified the technique used in acupuncture into a procedure similar to Hong’s dry needling technique. Therefore, in a ‘broad sense’ acupuncture can be considered as one type of dry needling.

Origin of Fu’s subcutaneous needling

The following three sources led to FSN’s evolution from traditional acupuncture.

Contemplation of De-Qi

De-Qi or Qi (Cheng 1987) is an acupuncture phenomenon that occurs during needle manipulation, experienced by the patient as a particular sensation, e.g. soreness, aching, numbness, or ‘needle grasp,’ or by the acupuncturist as a pulling sensation (Li, 199, Langevin et al. 2006, White et al. 2008). Traditionally, De-Qi must be achieved in the process of acupuncture regardless of the manipulation used; otherwise, the therapeutic results are poor (Cheng 1987). In every textbook on acupuncture in Chinese, the importance of De-Qi is always emphasized and reiterated and acupuncturists repeatedly highlight De-Qi. As a result, most Chinese patients believe in the adage, ‘no De-Qi, no effect.’ Sometimes, patients will be disappointed in the acupuncturist if they fail to acquire De-Qi, even though it may cause discomfort to the patient.

Acupuncturists and patients are not the only ones who consider De-Qi to be pivotal. Some scientists also believe that De-Qi plays an important role in acupuncture analgesia (Cao 2002, Park et al. 2002). Acupuncture needling may activate afferent fibers of peripheral nerves to elicit De-Qi, the signal of which ascends to the brain, activates the anti-nociceptive system, including certain brain nuclei, modulators (opioid peptides) and neurotransmitters, and through the descending inhibitory pathway results in analgesia (Cao 2002).

However, occasionally acupuncture does work without De-Qi and could fail even when the patients achieve strong De-Qi. Furthermore, many acupuncture substitutes, such as cupping, moxibustion, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and so on, do not elicit De-Qi, but they appear to be effective nevertheless (Chen & Yu 2003).

Therefore, De-Qi may be not as relevant as traditionally is often suggested. To prove the insignificance of De-Qi, the best method is to stimulate the tissue without obvious direction and then observe what will happen. The elicitation of De-Qi is related to the needling depth (Lin 1997). There are few free nerve endings and proprioceptive receptors in the subcutaneous layer, whereas free nerve endings are abundant in the epidermis and dermis. Proprioceptive receptors do exist in the muscular layer (Tortora 1989). Therefore, there should be no occurrence of De-Qi even if the subcutaneous layer is stimulated. Under such a condition, does the needling effect still exist? For an acupuncturist, it is easy to verify the existence of the needling effect, and this simple trial was one of several factors resulting in the discovery and development of FSN. One example of a form of acupuncture where achieving De-Qi has been shown to not be critical is wrist-ankle acupuncture.

Clinical application of wrist-ankle acupuncture

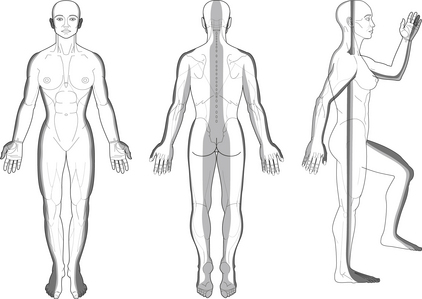

Wrist-ankle acupuncture (WAA) (Jiang et al. 2006) is also called wrist-ankle needling (Song & Wang 1985). Dr Xinshu Zhang, a neurologist who has worked at the Second Military Medical University in Shanghai, developed WAA in 1972. WAA divides the whole body into 12 longitudinal regions, six for each half of the body (Figure 15.4).

There are 6 points 2 cun (about 50 mm) above the wrist joint corresponding to the 6 regions above the diaphragm, and there are 6 points 3 cun (about 75 mm) above the ankle joint corresponding to the other 6 regions (Figure 15.5). A cun is a measure of distance relative to a person’s body dimensions commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine. If a disorder occurs in one of the regions, the corresponding point should be chosen. Unlike conventional acupuncture, WAA inserts an acupuncture needle only superficially in the subcutaneous layer; some authors claim that WAA is effective in the treatment of pain with various origins (Zhu & Wang 1998). Needling superficially in WAA wrist or ankle points to treat distant disorders often has a good effect (Song & Wang 1985, Chu & Bai 1997) leading to the idea that needling close to the afflicted area could be at least as effective as needling in an area remote from that which is afflicted, and that needling closer may be preferable. These thoughts motivated the principle author to seek answers through clinical trials.

Ancient techniques

Fu attempted to treat a patient with tennis elbow or lateral epicondylitis by needling the patient near the painful spot, which caused a positive response, and as such became the first successful case of FSN. From then on, a series of clinical trials were completed and positive results were commonly achieved. In the same year, Fu wrote a brief introduction to FSN, which was published in a Chinese health newspaper (Fu 1996).The following year Fu published his first research paper in Chinese in the Journal of Clinical Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Fu 1997).

Development of FSN

Innovation of the FSN needle

Fu realized that certain changes had to be made to the FSN needle; however, the challenge he faced was how to determine what kind of needle would go through the skin quickly and stay beneath the skin safely.

A patent application for the FSN needle was filed in December 1997. A Chinese invention patent was granted in August 2002 (Figure 15.6).

Increase of FSN indications

Stage 3: FSN was used to treat patients with benign painful visceral problems

FSN is performed superficially; hence, superficial illnesses such as soft tissue injuries were regarded as primary FSN indications. FSN was never expected to be used for the treatment of persons with visceral diseases, until an 80-year-old Chinese acupuncturist wrote the author that he had treated a patient with appendicitis using FSN. Although FSN may not always be suitable for the treatment of appendicitis for a variety of reasons, the letter implied that FSN may in fact be used in the treatment of persons with visceral diseases. From then on, FSN was used to treat individual with acute and chronic gastritis, cholecystitis, pain due to urinary calculus and painful menstruation, among others.

FSN manipulations

Structure of the FSN needle

FSN needles, individually packaged and pre-sterilized with ethylene oxide gas, are designed for single use. The FSN needle is made up of three parts (Figure 15.7): a solid steel needle core (bottom), a soft casing tube (middle), and a protecting sheath (top).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree