Functional and Dysfunctional ROM

In setting out to rehabilitate range of movement (ROM) the first task is to establish what is normal ROM and what is abnormal ROM; and this task is not as simple as it seems. Take two asymptomatic individuals and ask them to bend forwards to touch their toes. One will just about reach their knees while the other will place their hands flat on the floor. Which of these individuals has a normal ROM and which a pathological ROM, the stiffer individual or the hyperflexible individual? Does it matter if the stiffer person cannot reach their toes?

This chapter explores what constitutes ROM, in particular:

ROM Ingredients

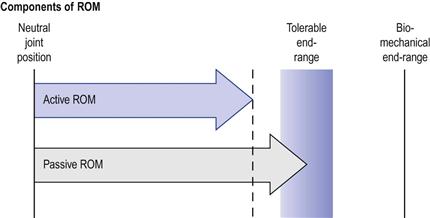

ROM is composed of active and passive movement components. The active ROM is generated by voluntary muscle activation. The passive ROM is the extent to which a joint or a limb can be moved in the absence of voluntary contraction (Fig. 2.1).

Daily activities are mostly voluntary and are therefore performed within the active ROM.1–5 This, as will be discussed later, has important implications for ROM rehabilitation (Ch. 8). Passive ROMs often constitute a smaller proportion of functional activities. For example, during the terminal phase of walking the ankle is “passively” dorsiflexed by the forward shift of the body over the extended leg. However, such movements are not fully passive. They are often controlled by eccentric activity in the antagonistic muscles. Passive ranges are also observed in particular postures or at rest: passive ankle dorsiflexion during a full squat, spinal side bending while side-lying, or hyper-extension of the wrist when kneeling on all fours. In many of these postures, body weight provides the forces necessary to attain the passive ranges.

Active end-range

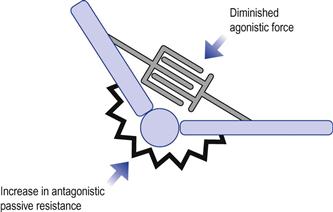

The active end-range is predominantly determined by the contraction forces generated by the muscles and the resistance from the antagonistic tissues. As movement approaches the end-range the agonist muscle’s contraction force tends to diminish progressively while, conversely, the passive resistance from antagonistic tissues tends to rise (Fig. 2.2).

Several factors can influence the active end-range. If you actively extend your index finger the range will be different depending on whether the wrist is held in flexion or extension; so positioning of adjacent joints/limb plays an important part in this range. Also, if you repeat the movement several times, fatigue will set in and you may find that the full range is progressively more difficult to attain. There are many other factors that can affect the active end-range: abnormal shortening of connective tissues, local sensitivity, pain, muscle atrophy, loss of motor control, excessive activity in the antagonistic pair, fear of movement, and many more. So the active end-range is highly variable. But what about the passive end-range? Is it absolute?

Passive end-range

In most joints, the passive ROM is a measure of the individual’s tolerance to discomfort or pain and not a true measure of range (Fig. 2.1). If you pull your index finger into extension the end-range will be determined by how much you can tolerate discomfort or pain (see stretch tolerance, Ch. 10). If a goniometer was at hand this position would be measured as the full extension range. However, the extension range would increase further if we were to anaesthetize the area and apply a greater force. So the painful range does not necessarily represent the full biomechanical range. This would apply to joints in which end-ranges are limited by soft-tissue resistance such as the spine, shoulder, hip and ankle, but not where there is bony apposition, such as in elbow extension.

So passive end-range is determined by stretch tolerance, which, by itself, can be highly variable and influenced by numerous factors. For example, sensitivity has natural variations during the day; a stretch performed with discomfort in the morning may be easier in the evening. An individual who stretches regularly will often complain of “good” and “bad” agility days. Sensitivity can change transiently simply as a result of repeating the same movement several times. Stretch the index finger into extension and then repeat it. On the second stretch you will find that it extends further with less discomfort (see creep deformation, Ch. 4). This means that the passive end-range is a vague clinical construct, highly variable and not an absolute measurement as we are often led to believe.6

ROM and sensitivity

End-ranges become even more blurred in conditions in which ROM losses are accompanied by pain and sensitization. In these conditions there is reduced tolerance to stretching and the experience of pain and stiffness determines the end-ranges. As a consequence, passive and active ROM losses can be due to elevated stretch sensitivity, but without physical changes in the length or stiffness of the tissues. For example, patients with low back pain often complain of increased spinal and hamstring stiffness in forward bending. However, they have the same flexion ROM as asymptomatic individuals.7–10 Hence, stretching the back and the legs, a common exercise given to patients with chronic back pain, is unlikely to have any therapeutic value (since nothing is short, it just feels like it).

The variability of tolerance can complicate and add uncertainty to ROM assessment and treatment. We can never be sure how much of the ROM loss is due to “real” biomechanical limitations or is simply because the patient cannot tolerate the discomfort. Furthermore, because the end-range is experiential and not a mechanical phenomenon it provides inaccurate feedback during stretching; it can be difficult to determine how much force to use during stretching. If the area is highly sensitized the patient may terminate the stretching long before it reaches effective levels. Pain and sensitivity can also confuse the treatment progression. Unpredictable adverse reactions and fluctuating sensitivity can overshadow positive biological–adaptive ROM changes. A further discussion of this topic can be found in Chapters 9 and 10.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree