Fractures of the Upper Extremity

David A. Volgas

Rena L. Stewart

Fractures of the upper extremity occur in approximately one third of all multitrauma patients. These injuries will have a profound impact on the patient’s recovery because they often preclude the use of crutches and even wheelchairs. Injuries to the upper extremity associated with blunt trauma are indicative of injury to deeper structures such as lung and heart. The trauma surgeon must look past the obvious deformity or blood and focus on the deeper structures which may endanger the patient’s life. In general, fractures of the upper extremity heal within 6 to 8 weeks. The section will describe the various types of upper extremity fractures, the operative indications, and general approach to the management of these injuries.

FRACTURES OF THE SCAPULAR BODY

The scapula is a flat bone that lies approximately 30 degrees to the chest wall posteriorly. It is quite mobile under normal circumstances. It is very thin, in most places only 1 mm thick. It is covered by the origin of the rotator cuff muscles anteriorly and posteriorly. Also, the medial border serves as the insertion of the rhomboids and levator scapula and more inferiorly of the serratus muscles. Fractures can be adequately imaged by standard radiography and it is rare that a computed tomography (CT) scan is needed.

Scapula fractures occur as a result of direct penetrating trauma such as a gunshot wound or, more commonly, as a result of blunt trauma to the chest wall and shoulder. Because they are generally treated nonoperatively, their greatest importance is that they are a harbinger of significant thoracic trauma. The presence of a scapula fracture should lead the surgeon to consider other diagnoses such as pulmonary contusion, multiple rib fractures, pneumothorax, or cardiac contusion.

Treatment typically consists of sling immobilization for comfort as well as early range of motion exercises. On rare occasions, fragments of the scapula can be oriented at right angles to their normal position and may cause skin breakdown or lung penetration. They may prompt the orthopaedic surgeon to perform an open reduction or excision of the offending fragment.

SCAPULOTHORACIC DISSOCIATION

Scapulothoracic injuries are rare but serious injuries which indicate tremendously high-energy trauma.1 They are generally caused by a traction injury to the upper extremity and involve the near-amputation of the shoulder girdle from the torso. They can be life threatening when the injury causes disruption of the subclavian vein or artery.2,3 Morbidity is universal even with prompt recognition and treatment. Vascular injury occurs in >80%,3 while permanent neurologic injury occurs in 94%. There is a 10% mortality associated with these injuries primarily due to hemorrhagic shock. The diagnosis may be delayed when the injury is a closed injury. The telltale radiographic sign of lateralization of the scapula may be overlooked if there is a low index of suspicion.

A vascular surgeon or an experienced trauma surgeon should be called immediately if scapulothoracic dissociation is suspected.4 Repair is difficult, because of the traction nature of the vascular injury. There is often a wide zone of injury to the artery and there may be persistent vasospasm. Additionally, the vein may be torn from its origin

or in the axilla. A wide approach, which may include a supraclavicular approach, may be required. The clavicle may be divided with a saw to permit better visualization of the vessels as they travel laterally.

or in the axilla. A wide approach, which may include a supraclavicular approach, may be required. The clavicle may be divided with a saw to permit better visualization of the vessels as they travel laterally.

GLENOID FRACTURE

Glenoid fractures are uncommon fractures of the scapula. They are generally caused by direct blunt trauma to the chest wall and may therefore be a sign of more significant injury to the lungs. In isolation, glenoid fractures can often be managed nonoperatively, but when displaced >2 mm, they may require operative treatment. Operative treatment can safely be delayed 10 to 14 days to allow recovery from the associated lung injury. The surgical approach is normally posterior, with the patient in a lateral decubitus position for 2 to 4 hours, depending on the experience of the surgeon.

CLAVICLE FRACTURES

The clavicle is an “S” shaped bone which articulates the sternum medially (the sternoclavicular joint) and the acromion laterally (the acromioclavicular or A-C joint). The function of the clavicle is to both suspend the shoulder and to act as a strut to keep the shoulder at an appropriate distance away from the body. Clavicle fractures are the most common fracture in the human body, comprising 3% to 10% of all fractures.5 They are seen most frequently in young, active individuals and result from force applied to the upper extremity and transmitted to the thorax or, infrequently, a direct blow to the clavicle.6,7 Although only a small percentage of clavicle fractures are “open” or “compound” injuries, the open clavicle fracture should alert the trauma surgeon to the possibility of concomitant life-threatening injury. The largest review of this topic revealed that open clavicle fractures are associated with head injury in 65% of cases, pulmonary injury in 75%, spine fractures in 35%, and facial trauma in 55%.8 Like all open fractures, open fractures of the clavicle are surgical emergencies.

In the past, clavicle fractures were thought to be a benign injury and were treated almost exclusively nonoperatively. This treatment strategy was based on early reports that showed that virtually all clavicles “healed” with nonunion rates of <1%.9 However, surgeons are now rethinking the treatment of these common injuries as new data comes to light regarding functional outcomes and union rates. An understanding of this paradigm shift is important for the general surgeon treating trauma patients. The traumatologist is frequently the only surgeon caring for a patient with a clavicle fracture, because orthopaedic consultation has traditionally been rare for closed clavicle fractures. New evidence suggests that referral to an orthopaedic surgeon for evaluation of most clavicle fractures is extremely important.

There are two significant problems with nonoperative treatment of clavicle fractures, particularly fractures which are significantly displaced (usually shortened). The first factor is that careful review of existing literature reveals a much higher rate of nonunion than previously thought. In a systematic review of all English literature, the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group revealed that the nonunion rate is actually 6% for all fractures and rises to 15% for displaced fractures, more than 10 times the rate previously thought.10 The second factor encouraging more frequent operative management is that patients are much less satisfied with the outcomes of nonoperative management than previously believed.7,11,12,13,14 A study of “healed” fractures revealed that at >4 years after the fracture, 50% of patients were partially or totally dissatisfied with their outcome and 40% had been unable to return to their previous work.15 This poor functional outcome for patients is related to the fact that displaced clavicle fractures heal in a shortened position and cause significant changes in the biomechanical functioning of the shoulder (see Fig. 1).

Evaluation of clavicle fractures should include careful examination of the neurologic and vascular status of the upper extremity and also of the skin overlying the

clavicle to look for “skin tenting.” While almost all clavicle fractures will cause swelling and some stretching of the skin over the displaced fragments, true skin tenting is rare and represents a serious condition requiring urgent orthopaedic consultation. If the skin is blanched or necrotic, an orthopaedic surgeon should be summoned without delay. In the past, treatment with a figure-of-eight brace was thought to pull clavicle fractures back into a better position and thereby remove the pressure on the skin. Studies have shown that this is not the case and fracture position is unchanged with the use of a figure-of-eight brace (compared to a simple sling).16 This type of brace is also extremely uncomfortable and results in high rates of patient dissatisfaction. Therefore, treatment with figure-of-eight brace has largely been abandoned. Nonoperative management now consists of treatment in a sling for a short period of time (not more than 2 weeks) followed by early range of motion exercises.

clavicle to look for “skin tenting.” While almost all clavicle fractures will cause swelling and some stretching of the skin over the displaced fragments, true skin tenting is rare and represents a serious condition requiring urgent orthopaedic consultation. If the skin is blanched or necrotic, an orthopaedic surgeon should be summoned without delay. In the past, treatment with a figure-of-eight brace was thought to pull clavicle fractures back into a better position and thereby remove the pressure on the skin. Studies have shown that this is not the case and fracture position is unchanged with the use of a figure-of-eight brace (compared to a simple sling).16 This type of brace is also extremely uncomfortable and results in high rates of patient dissatisfaction. Therefore, treatment with figure-of-eight brace has largely been abandoned. Nonoperative management now consists of treatment in a sling for a short period of time (not more than 2 weeks) followed by early range of motion exercises.

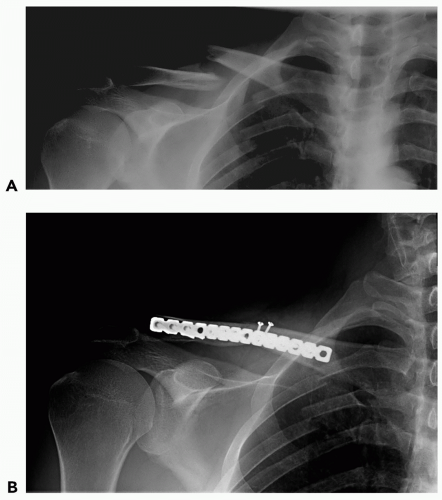

Figure 1 A “healed” clavicle fracture after nonoperative treatment. Note the significant shortening of the clavicle. |

Operative management has recently been shown in a randomized controlled trial to yield superior results for displaced clavicle fractures.17 Therefore, referral to an orthopaedic surgeon is appropriate for virtually all clavicle fractures, with the possible exception of nondisplaced fractures. Although no consensus exists on the definition on a “displaced fracture,” there is agreement that any fracture that has shortened >1 cm and/or displaced more than the width of the clavicle should be evaluated by an orthopaedic surgeon (see Fig. 2A). Several methods of operative fixation of clavicle fractures exist including plates and screws (most common) (see Fig. 2B) and screws or pins placed in the central medullary cavity of the bone.17,18,19,20,21

SHOULDER DISLOCATION

Shoulder dislocations are common and are often seen as a result of a sports-related injury. They may also occur during falls (especially in the elderly), after high-energy impacts, or after seizures. The most common dislocation is anteroinferior. Rarely, a posterior dislocation may occur and it is most often seen after seizures or electric shock. The rarest dislocation is a straight inferior dislocation, termed luxatio erecta, because the patient presents with the arm fully raised, as if raising the hand in class.

Treatment is normally simple and most emergency department physicians are comfortable with the reduction. After conscious sedation, a sheet is looped around the torso under the arm of the affected side. An assistant is asked to provide countertraction by simply pulling on the sheet from the other side of the patient, whereas the surgeon grasps the arm with the elbow in extension and the arm abducted approximately 30 degrees. Moderate traction and adequate sedation will usually accomplish the reduction. Pain relief is immediate after reduction. Alternatively, a 10-1b weight can be tied to the arm while the patient is lying prone on a gurney or table with the arm hanging down. After approximately 10 to 15 minutes, with adequate sedation, the shoulder will spontaneously reduce.

If the shoulder cannot be reduced, an orthopaedic surgeon should be contacted. Postreduction treatment depends on the patient’s age. Young patients have a much higher redislocation rate than older patients. Because of this, many orthopaedic surgeons recommend operative treatment to reinforce the anterior capsule acutely, but others prefer to give 6 weeks of physical therapy and only consider surgical treatment if the patient dislocates a second time. A shoulder immobilizer or sling is used until the patient can follow up with an orthopaedic surgeon.

Complications of shoulder dislocation include redislocation, axillary nerve injury, and musculoskeletal nerve injury. Vascular injuries are rare, but may occur.22,23,24,25 Most commonly venous thrombosis may occur, more commonly with luxatio erecta. Pseudoaneurysm of the axillary or brachial artery has also been reported.

THE “FLOATING SHOULDER”

The floating shoulder is a term used to describe ipsilateral fractures of the clavicle and glenoid neck. This injury is uncommon and treatment is controversial. Some surgeons advocate repair of one of the fractures to restore the shoulder girdle,26 whereas others advocate nonoperative treatment for both fractures.27 The consensus appears to be that operative fixation is reserved for fractures with marked displacement.26,28,29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree