10 Fractures of Other Locations

Fractures of the Patella (Segment 34)

Anatomic Features

Anatomic Features

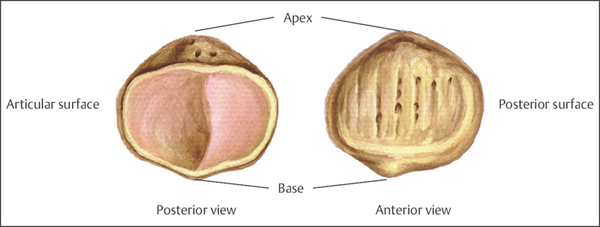

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the human body, and is an important component of the knee joint. It serves to increase the leverage of the quadriceps femoris as a fulcrum, protects the front of the joint, and maintains joint stability. It is a flat, triangular bone; its superior border is thick, while the medial and lateral borders are thinner, and it gives attachment to the tendon of the quadriceps femoris and the medial and lateral patellar retinacula. The lateral borders converge below to the apex, which gives attachment to the ligamentum patellae; the anterior surface is convex and rough, and covered by the expansion from the tendon of the quadriceps femoris; the posterior surface is a smooth, oval, articular area, and for the most part is covered with smooth, slippery cartilage; it is divided into two facets, medial and lateral, by a vertical ridge. Each facet is further subdivided into three facets: superior, middle, and inferior. Lateral to the inner facet is another longitudinal facet. These seven facets in total make contacts with the femur at various angles during the extension–flexion of the knee joint (Plate 10.1).

OTA Classification and Coding System for Patellar Fractures

OTA Classification and Coding System for Patellar Fractures

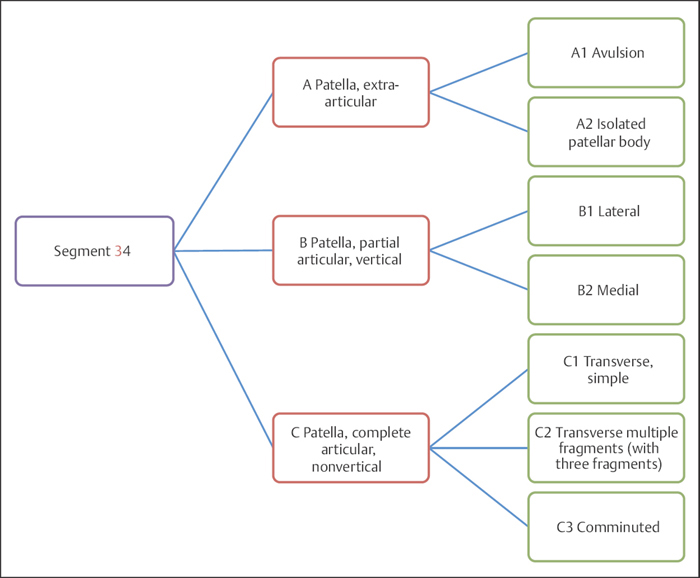

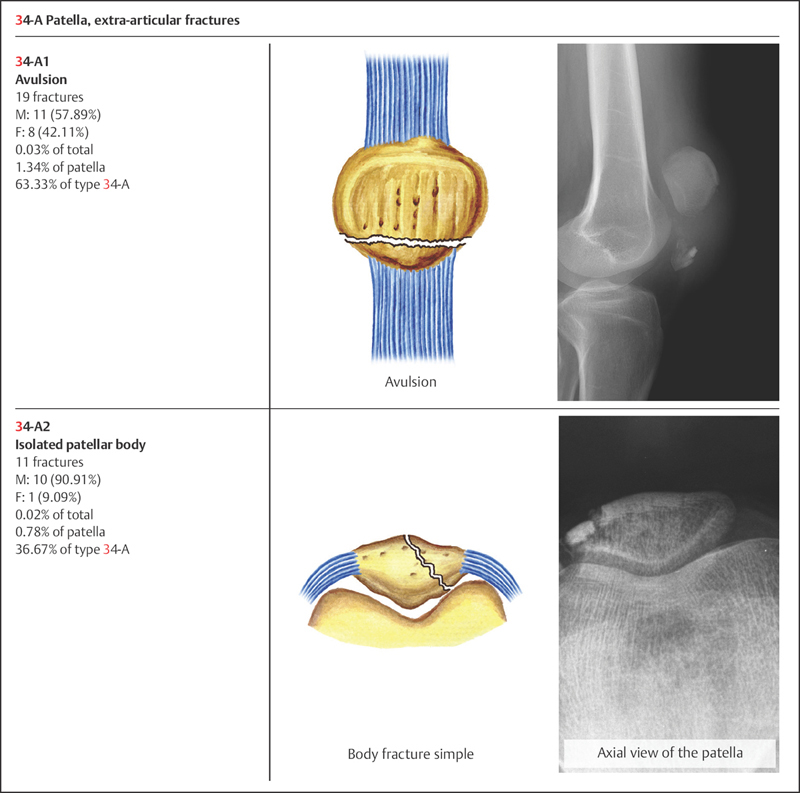

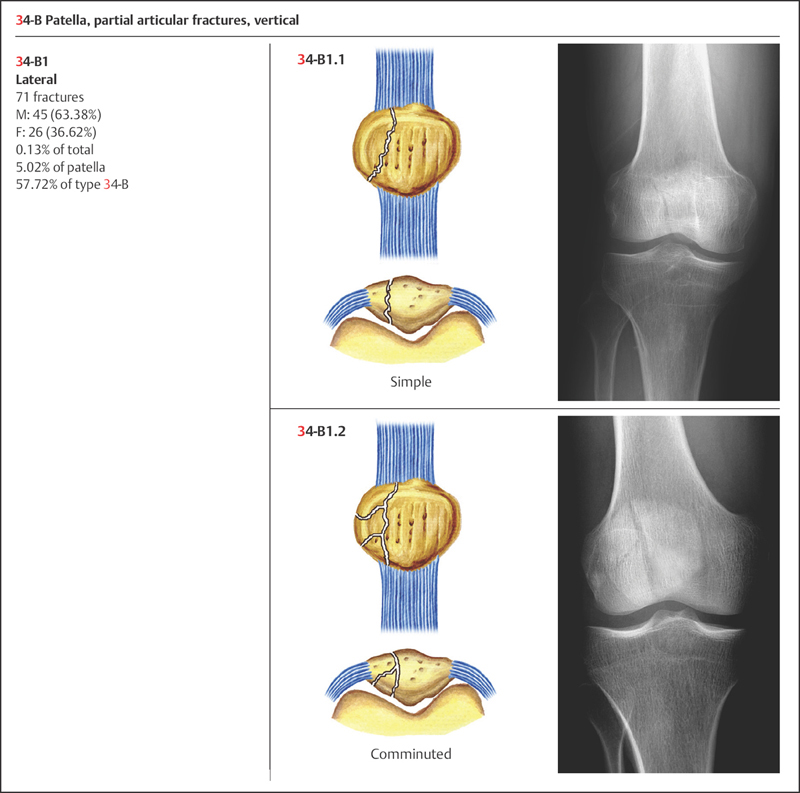

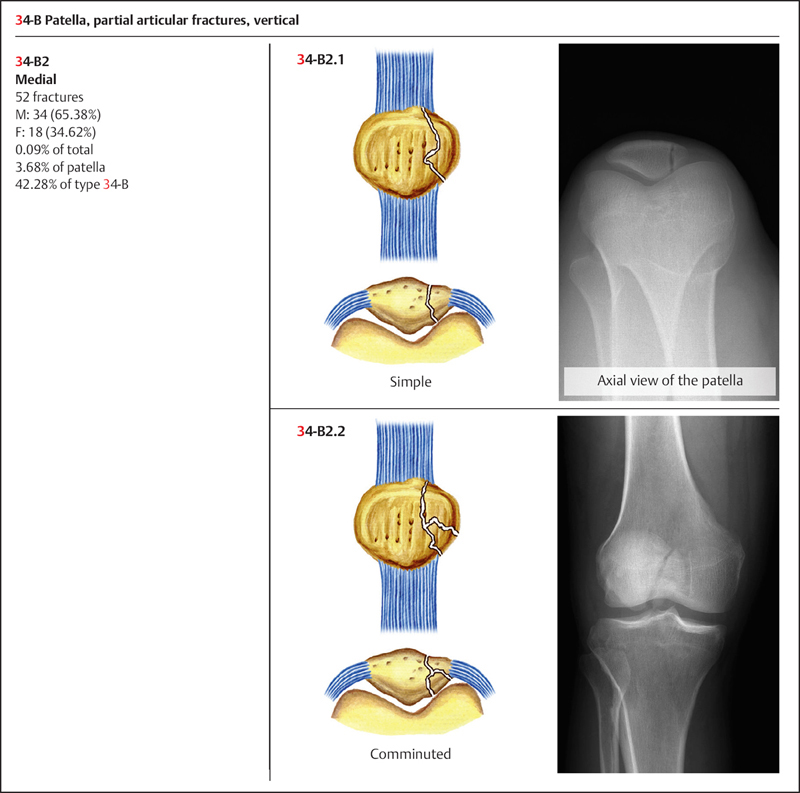

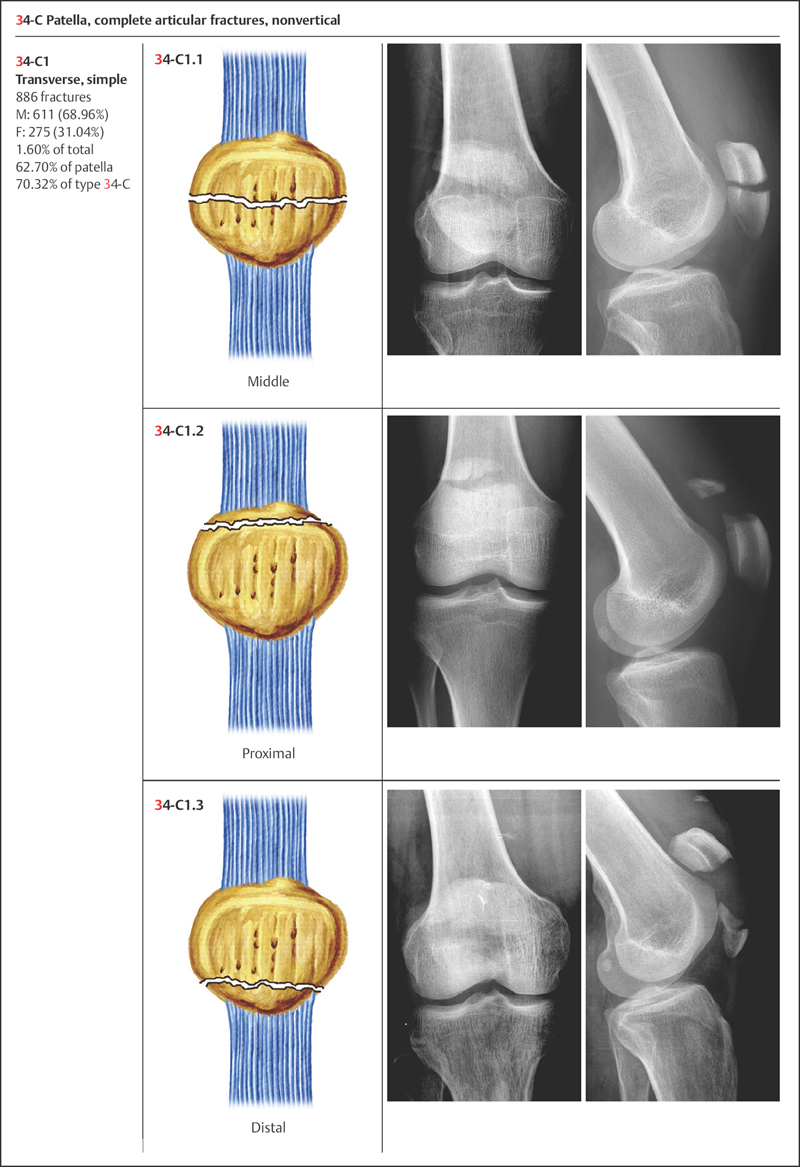

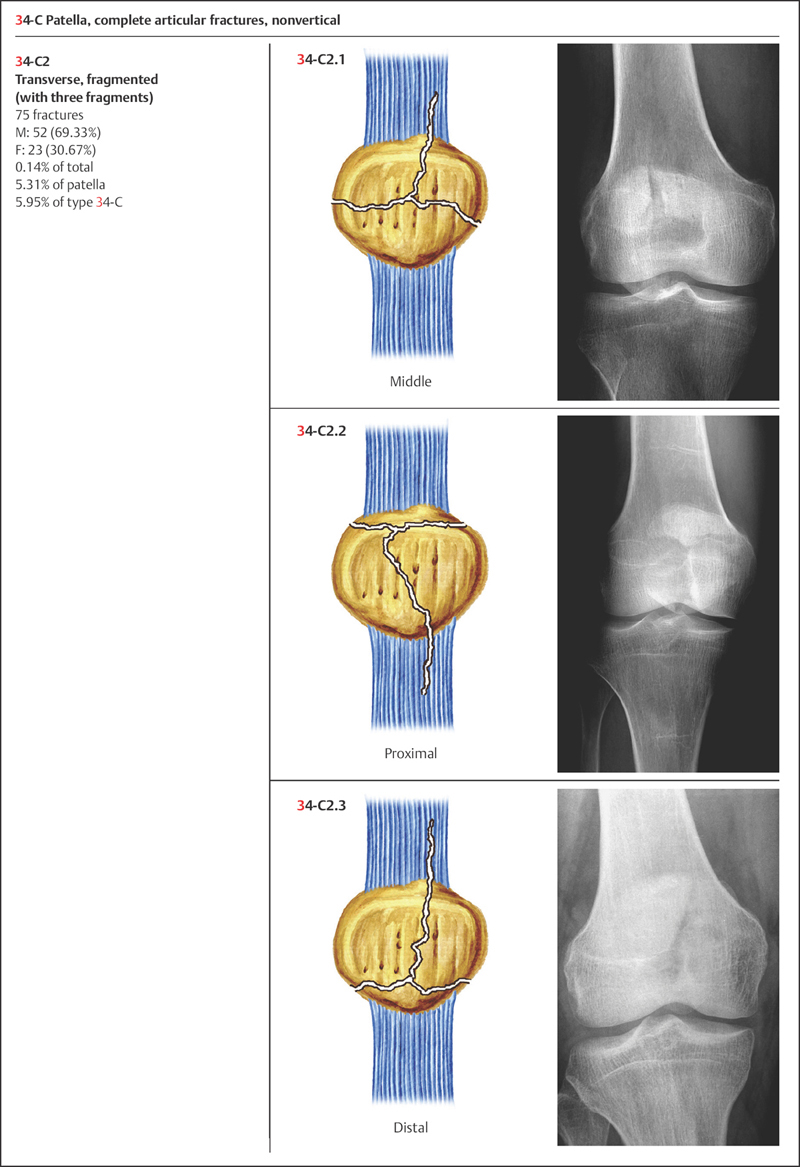

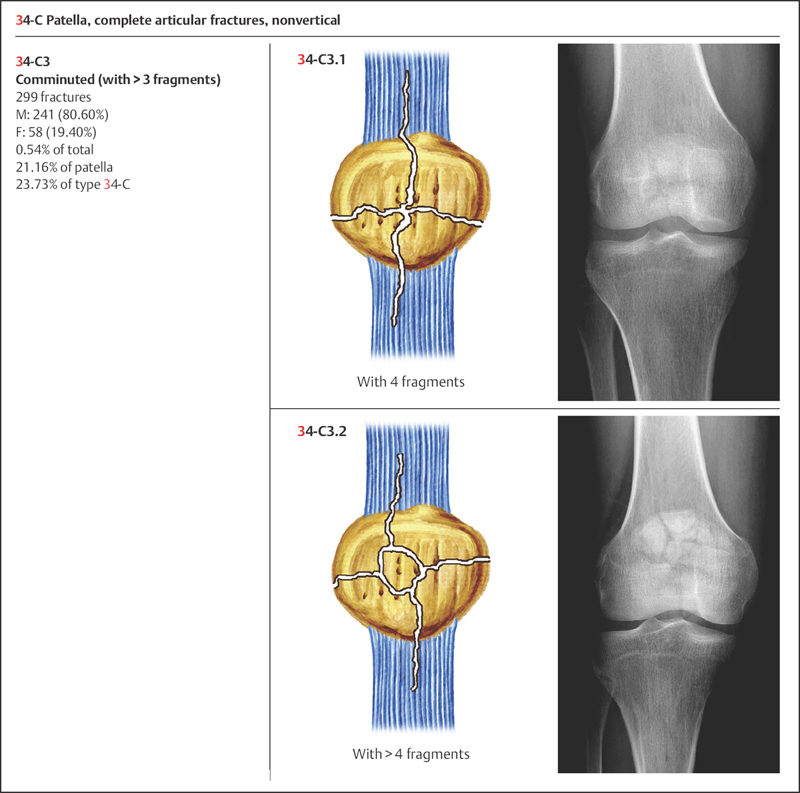

Based on Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) classification, the patella is coded as number “34” for its anatomic location. Patellar fractures are classified into three types according to the fracture pattern: type A: extra-articular; type B: partial articular, vertical; and type C: complete articular, nonvertical (Plate 10.5).

Plate 10.1

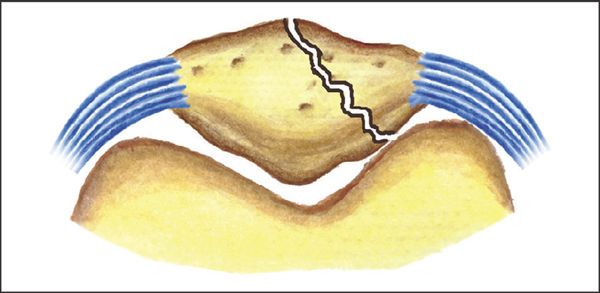

Plate 10.2

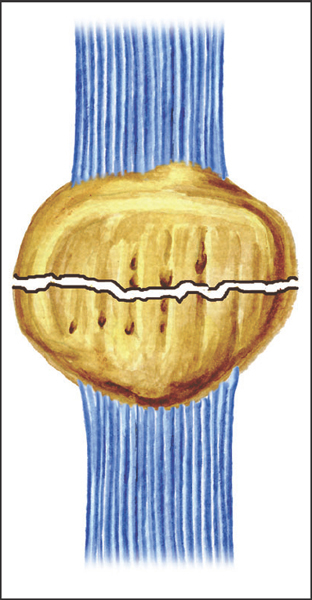

Plate 10.3

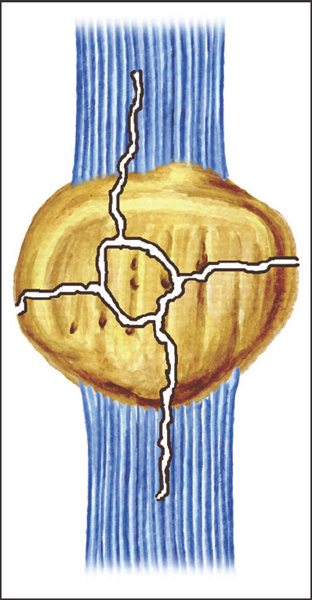

Plate 10.4

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Patellar Fractures (Segment 34)

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Patellar Fractures (Segment 34)

A total of 1429 patients with 1440 patellar fractures were treated at our trauma center over a 5-year period from 2003 to 2007. All cases were reviewed and statistically studied; the fractures accounted for 2.37% of all patients with fractures, and 2.21% of all kinds of fractures, respectively; of a total 1429 patients, there were 24 pediatric patients (27 patellar fractures) and 1405 adult patients with 1413 fractures.

Epidemiologic features of patellar fractures are as follows:

• more males than females

• more left-side than right-side fractures

• the high-risk age group is 41–50 years—the same age group for males, while for females the high-risk age group is 51–60 years

• the most common fracture type is type 34-C—the same fracture type for both males and females

• the most common fracture group is group 34-C1—the same fracture group for both males and females.

Plate 10.5

Patellar Fractures by Sex

Patellar Fractures by Sex

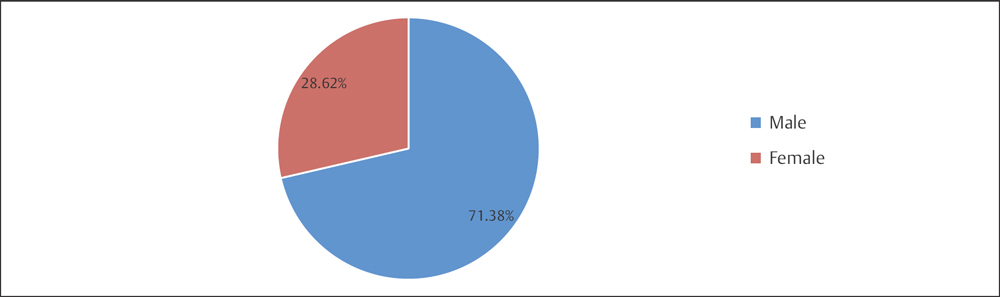

Table 10.1 Sex distribution of 1429 patients with patellar fractures

| Sex | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Male | 1020 | 71.38 |

| Female | 409 | 28.62 |

| Total | 1429 | 100.00 |

Fig. 10.1 Sex distribution of 1429 patients with patellar fractures.

Patellar Fractures by Fracture Side

Patellar Fractures by Fracture Side

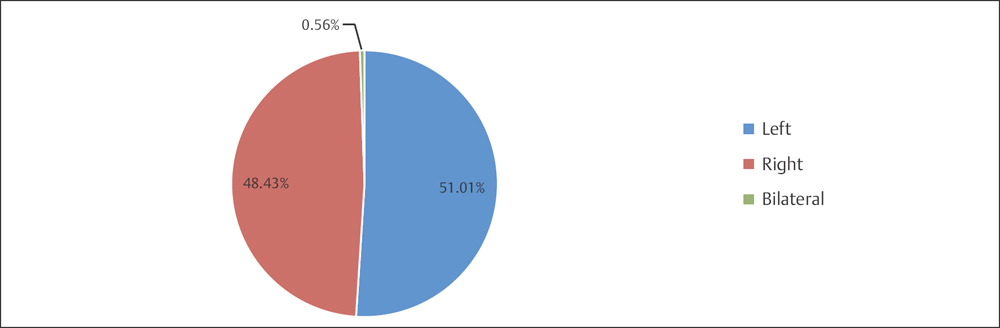

Table 10.2 Fracture side distribution of 1429 patients with Patellar fractures

| Fracture side | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Left | 729 | 51.01 |

| Right | 692 | 48.43 |

| Bilateral | 8 | 0.56 |

| Total | 1429 | 100.00 |

Fig. 10.2 Fracture side distribution of 1429 patients with patellar fractures.

Patellar Fractures by Age Group

Patellar Fractures by Age Group

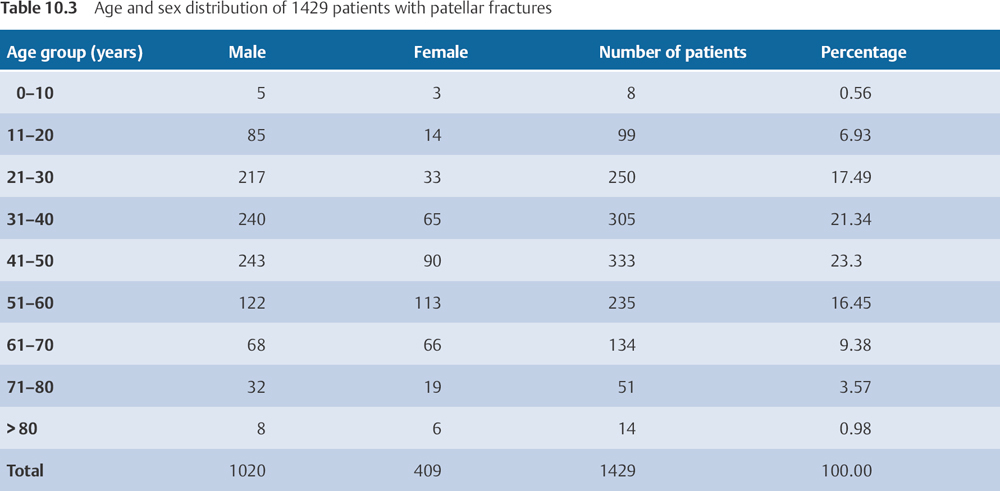

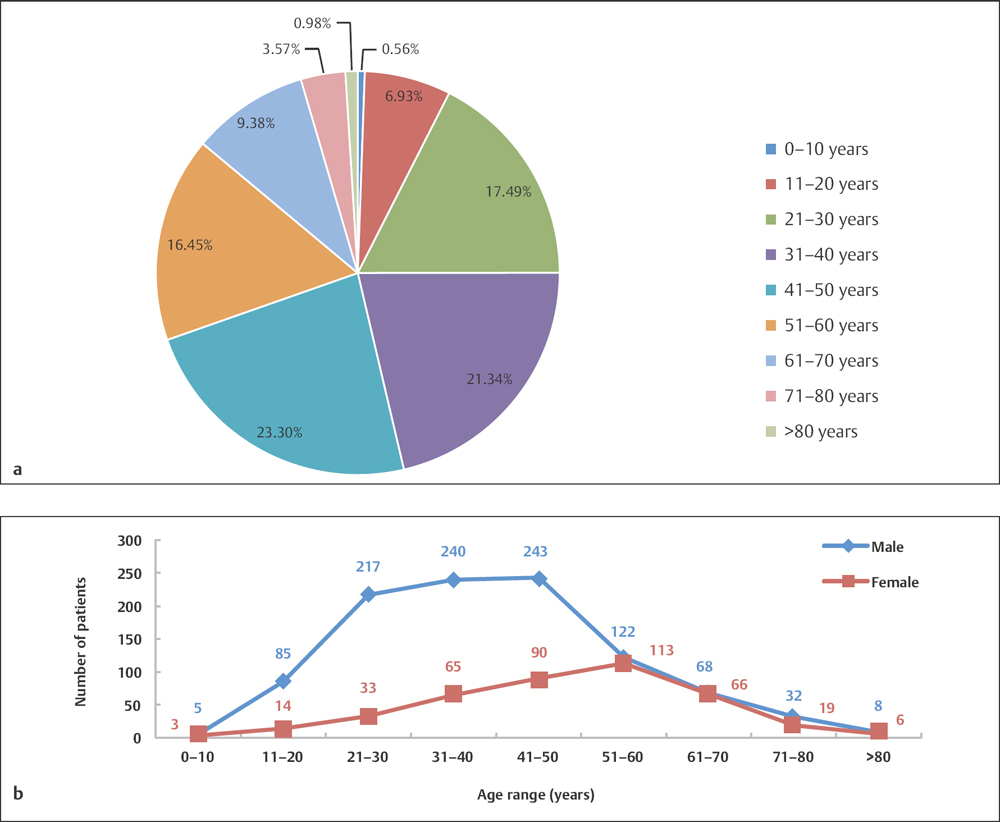

Fig. 10.3 a, b

a Age distribution of 1429 patients with patellar fractures.

b Age and sex distribution of 1429 patients with patellar fractures.

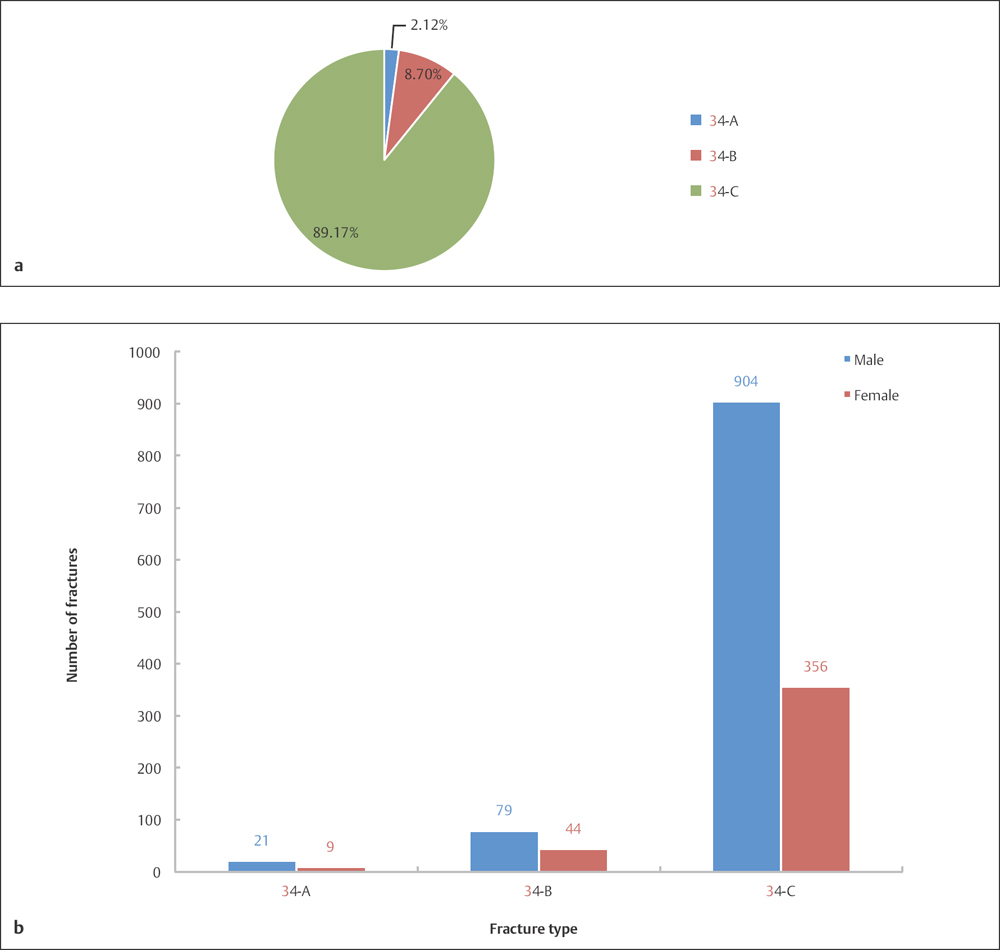

Adult Patellar Fractures by Fracture Type

Adult Patellar Fractures by Fracture Type

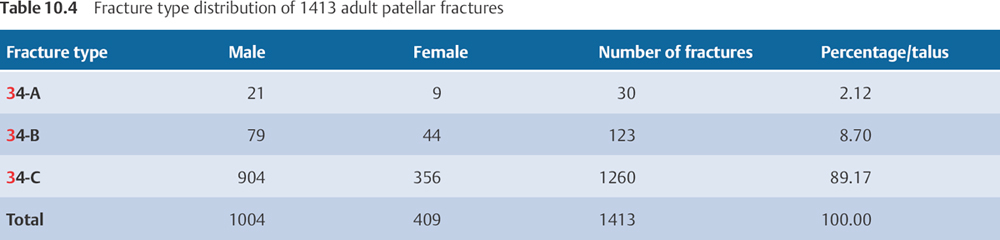

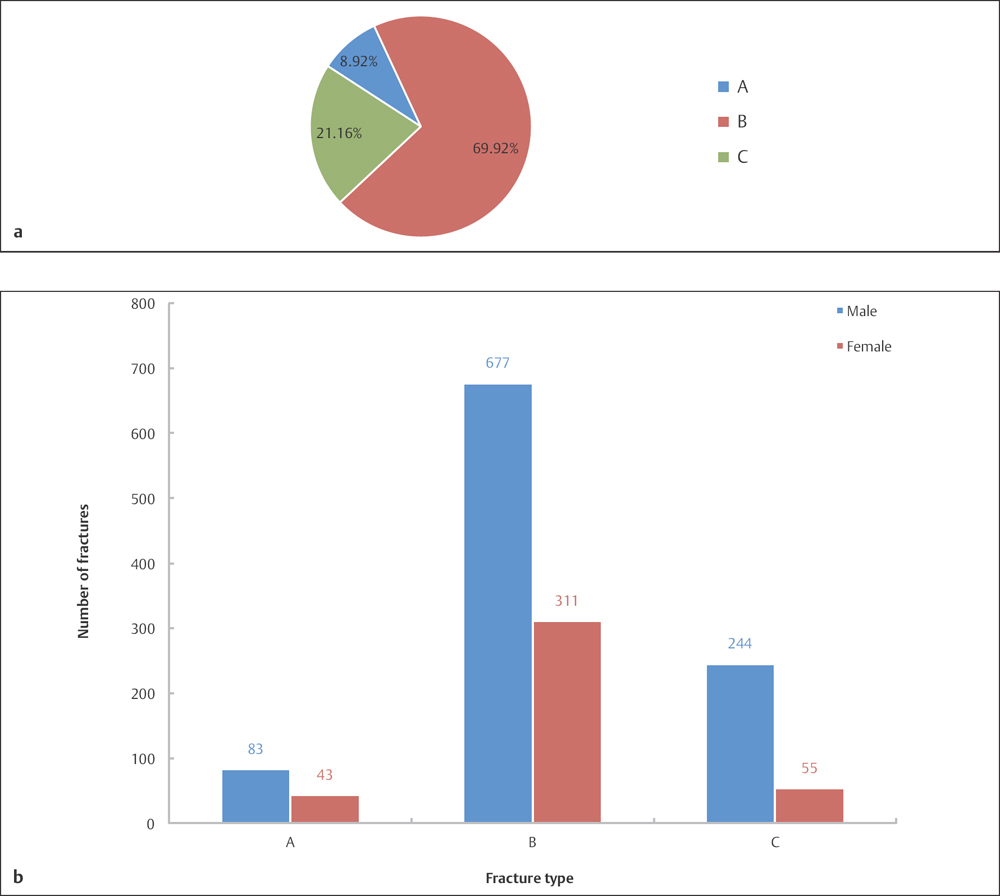

Fig. 10.4 a, b

a Fracture type distribution of 1413 adult patellar fractures by OTA classification.

b Sex and fracture type distribution of 1413 adult patellar fractures by OTA classification.

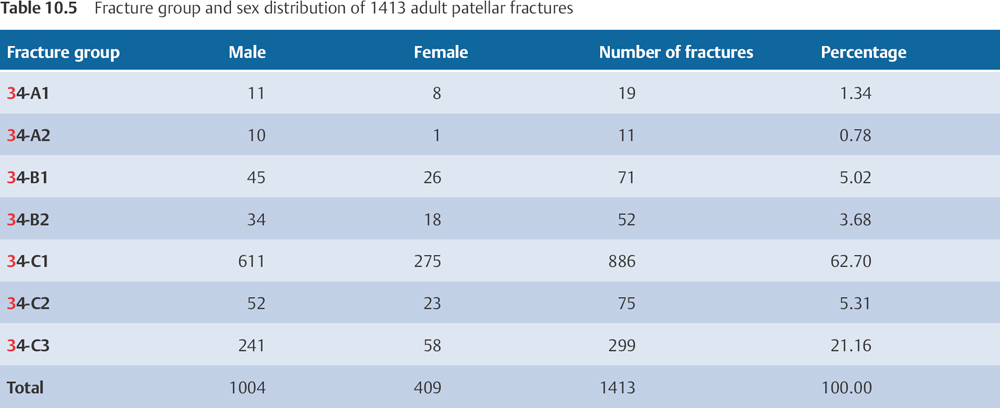

Adult Patellar Fractures by Fracture Group

Adult Patellar Fractures by Fracture Group

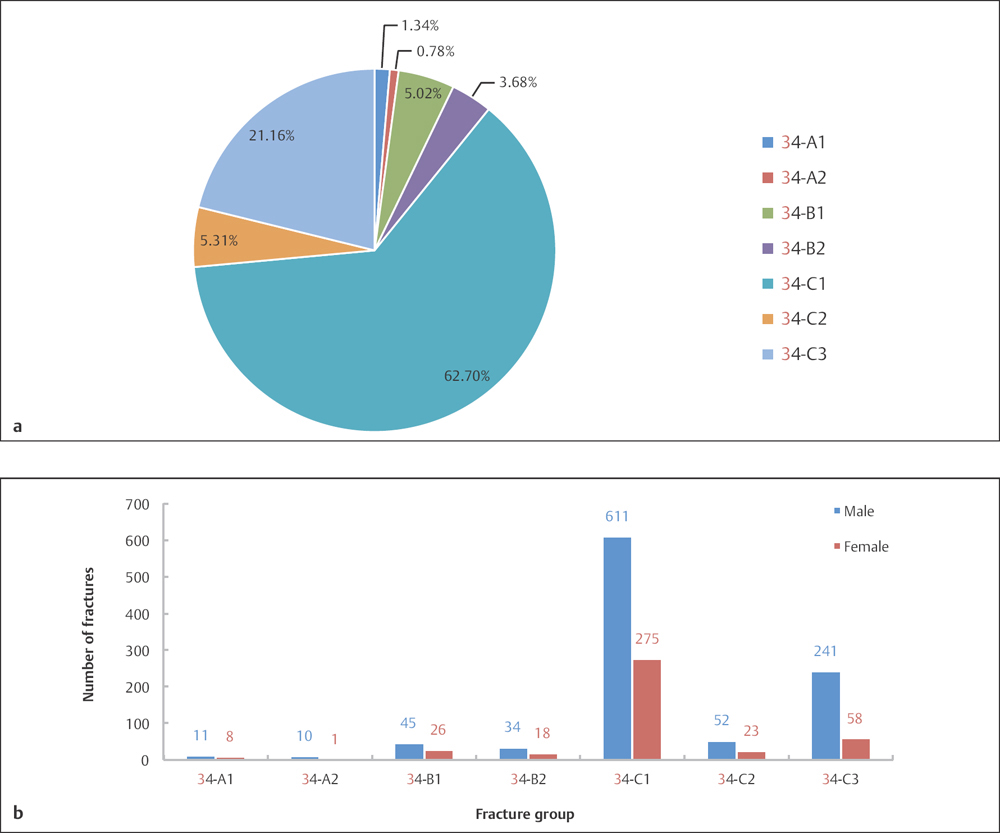

Fig. 10.5 a, b

a Fracture group distribution of 1413 patellar fractures by OTA classification.

b Sex and fracture group distribution of 1413 patellar fractures by OTA classification.

Injury of Mechanism

Injury of Mechanism

Transverse fractures of the patella and avulsion fractures of the superior and inferior poles are often caused by indirect mechanisms, seen with hyperflexion of the knee due to sudden tensile force of the quadriceps. Comminuted, vertical, and oblique fractures are more clearly associated with direct mechanisms, such as from direct blows and crush injuries. The energy of the impacting force, which results in comminuted fractures of the patella, may also cause damage to the articular cartilage of both the patella and the femoral condyles.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Patellar fractures usually present with a history of trauma. Physical examination reveals ecchymosis over the anterior aspect of the knee, hemarthrosis, swelling, tenderness, and partial to complete limitation of knee joint mobility. If fracture displacement is present, a gap between fragments and retropatellar crepitus can be noted. Radiographs of anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the knee joint usually confirm the diagnosis. If vertical or border fractures are clinically suspected, an axial view or computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee joint may be indicated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is necessary for comminuted patellar fractures due to damage of the articular cartilage of both the patella and the femoral condyles. The diagnosis of a vertical fracture of the patella should be differentiated from that of a patellar variation. Vertical fractures present with a clear trauma history, positive physical examination findings, fracture lines, and a jagged surface of the broken ends; this is in contrast to variations of the patella (binary or ternary patella), which are known to have wide gaps, smooth broken ends, or mild to absent physical signs/syndrome. In addition, the thin layer of cortex can be exposed.

Treatment

Treatment

If the fracture is displaced less than 3 mm, or the intra-articular step-off is less than 2 mm, the fracture may be treated with a nonoperative modality. However, for elderly patients, operative management with rigid internal fixation should be considered to allow early postoperative mobilization and to minimize knee fibroadhesive scar formation. In young healthy patients, patellar fractures can be treated with immobilization followed by casting, external fixation devices, and tuck loop fixation, etc. Surgical treatment is advised for displaced fractures, which are defined as fractures that have an intra-articular step-off of more than 2 mm or a separation of more than 3 mm. Additional caution should be taken for pediatric patients with patellar fractures when considering an operative approach, because operative procedures have the potential to damage growth cartilage, and subsequently impact the growth and development of the patella. Because children have a greater potential for tissue bone repair and molding, fractures with marked displacement, or even with a comminuted pattern, should initially be treated with nonoperative management. Partial surgical removal of the patella should be considered for severe comminuted fractures that are not able to be anatomically reduced. Severe comminuted patellar fractures in elderly patients should be treated with primary total surgical removal of the patella.

Further Classifications of Patellar Fractures

Further Classifications of Patellar Fractures

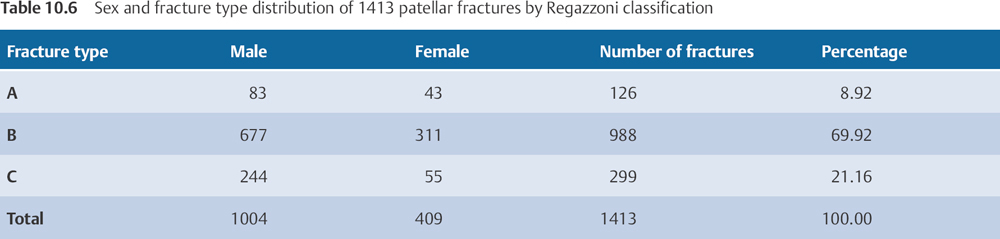

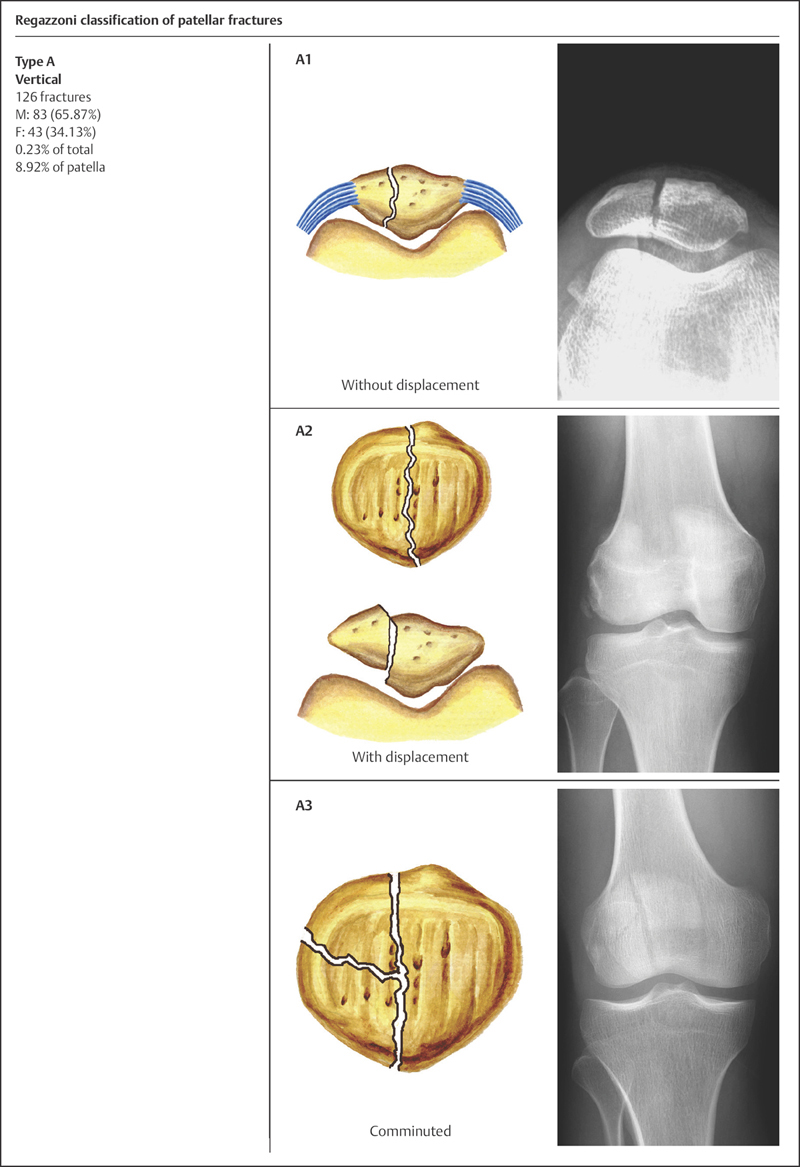

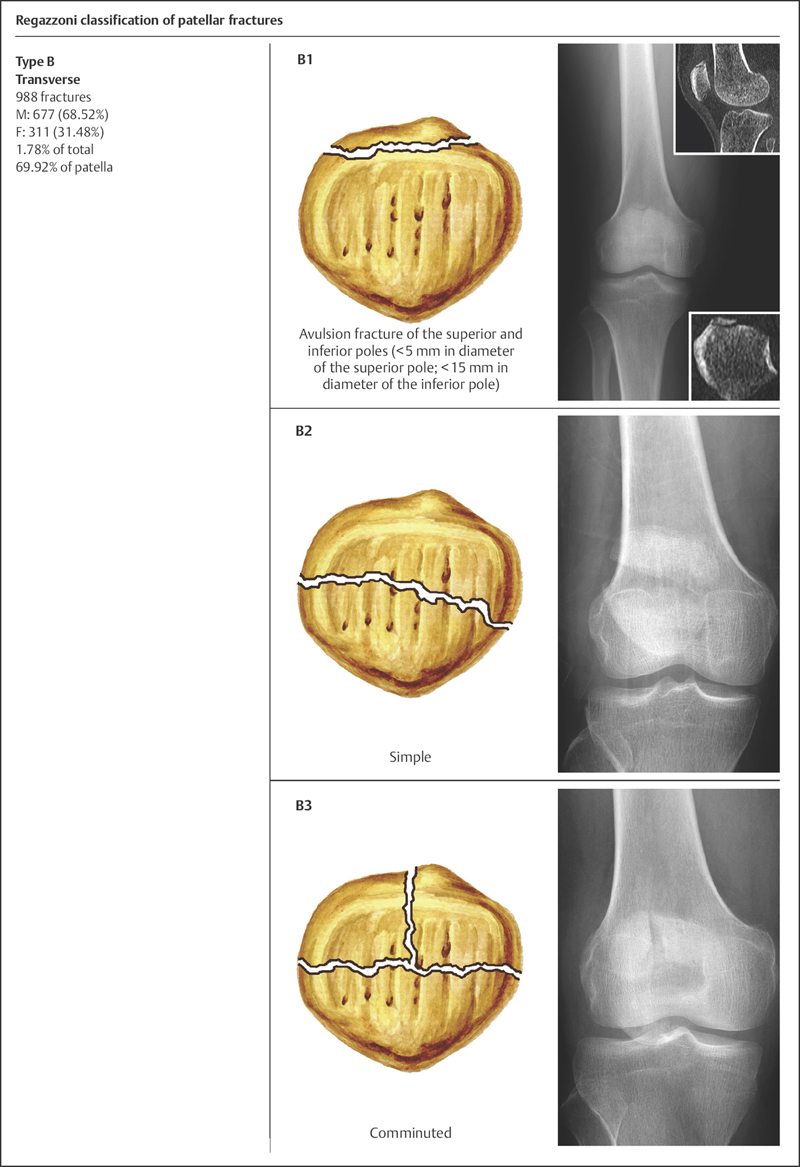

Regazzoni Classification

Based on the fracture location, pattern, and presence of displacement, Regazzoni classified patellar fractures into three types, with three subgroups for each fracture type.

• Type A: vertical fracture—A1: with no displacement; A2: with displacement; and A3: comminuted.

• Type B: transverse fracture—B1: avulsion fracture of the superior and inferior poles of the patella (< 5 mm in diameter at the superior pole, < 15 mm in diameter at the inferior pole); B2: simple; and B3 comminuted.

• Type C: comminuted fractures—C1: with no displacement; C2: with displacement of less than 2 mm; and C3: burst fractures with displacement of more than 2 mm.

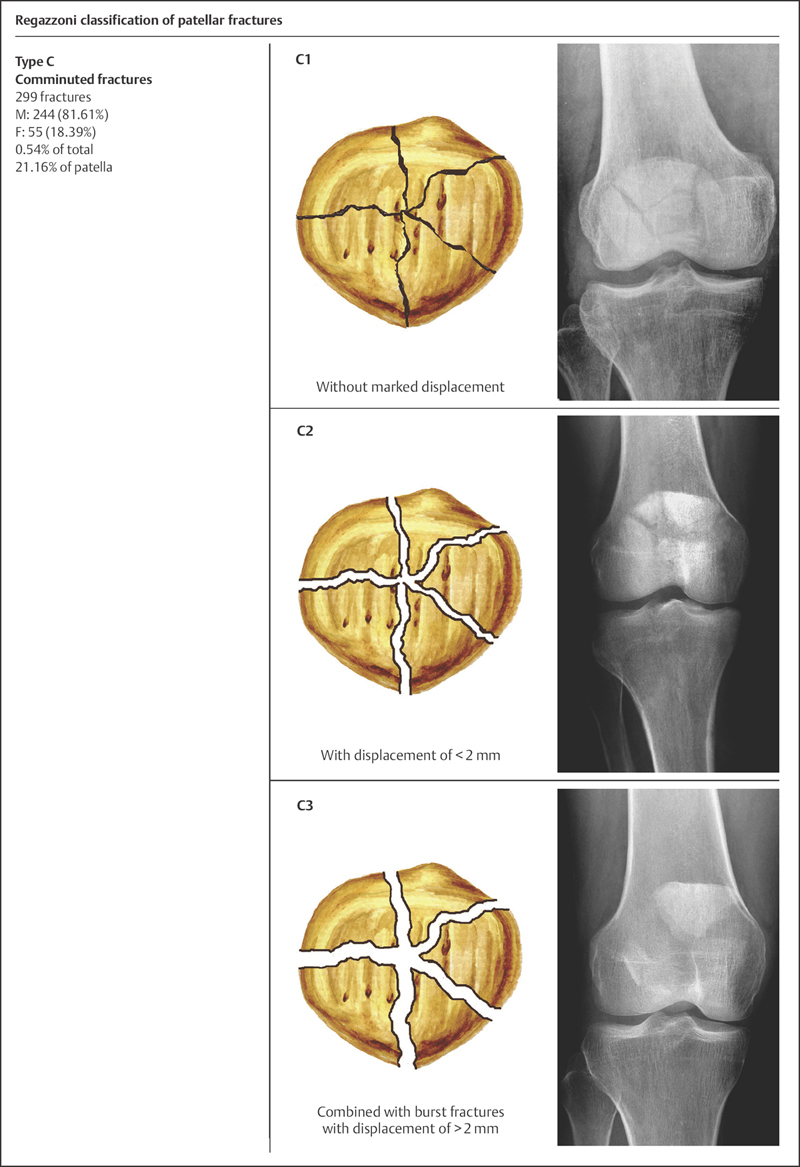

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Patellar Fractures by the Regazzoni Classification

A total of 1413 adult patellar fractures were treated at our trauma center over a 5-year period from 2003 to 2007; all cases were reviewed and statistically studied. Their epidemiologic features are as follows:

• more males than females

• the most common fracture type is type B (transverse).

Fig. 10.6 a, b

a Fracture type distribution of 1413 patellar fractures by Regazzoni classification.

b Sex and fracture type distribution of 1413 patellar fractures by Regazzoni classification.

Clavicle Fractures (Segment 15)

Anatomic Features

Anatomic Features

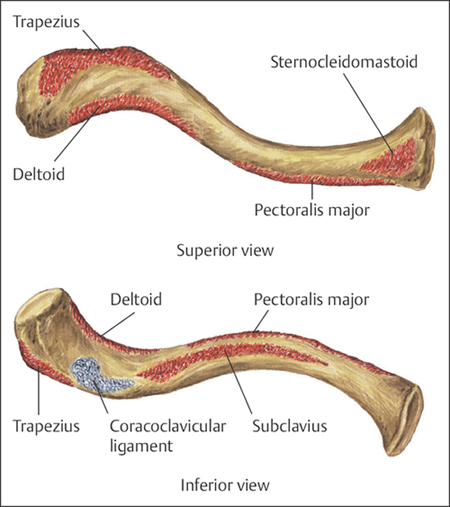

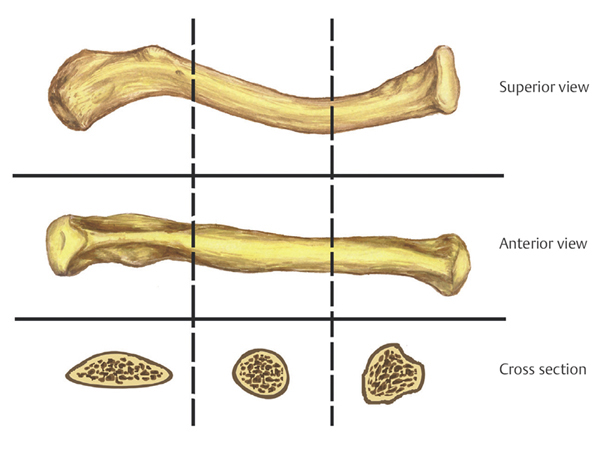

The clavicle forms the anterior portion of the shoulder girdle, and is placed nearly horizontally at the upper and anterior part of the thorax. It serves as the only direct bony attachment of the arm to the trunk. The clavicle is connected strongly to several muscles and, accordingly, to facets, most of which are essential for the stability of the shoulder girdle. It is a long bone, curved somewhat like the letter “s” in the superior view, but appears straight in the anterior view. The lateral one-third of the clavicle is flattened from above and downward, to accommodate the attachment and traction of muscles; furthermore, its middle one-third is tubular, and its medial one-third has a prismatic form to withstand the axial compression load and traction (Plate 10.6).

The lateral one-third of the clavicle gives attachment to the trapezius and deltoid muscles. On the posterior–superior border of the medial one-third, there is a rough area for attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The clavicular portion of the pectoralis major originates from the anterior surface of medial border of the medial one-third. The subclavius muscle originates from the inferior border of the middle one-third of the clavicle and inserts on the first rib, just dorsal to the subclavian surface (Plate 10.7).

Plate 10.6

Plate 10.7

Anatomic Features and Muscular Attachment of the Clavicle

Anatomic Features and Muscular Attachment of the Clavicle

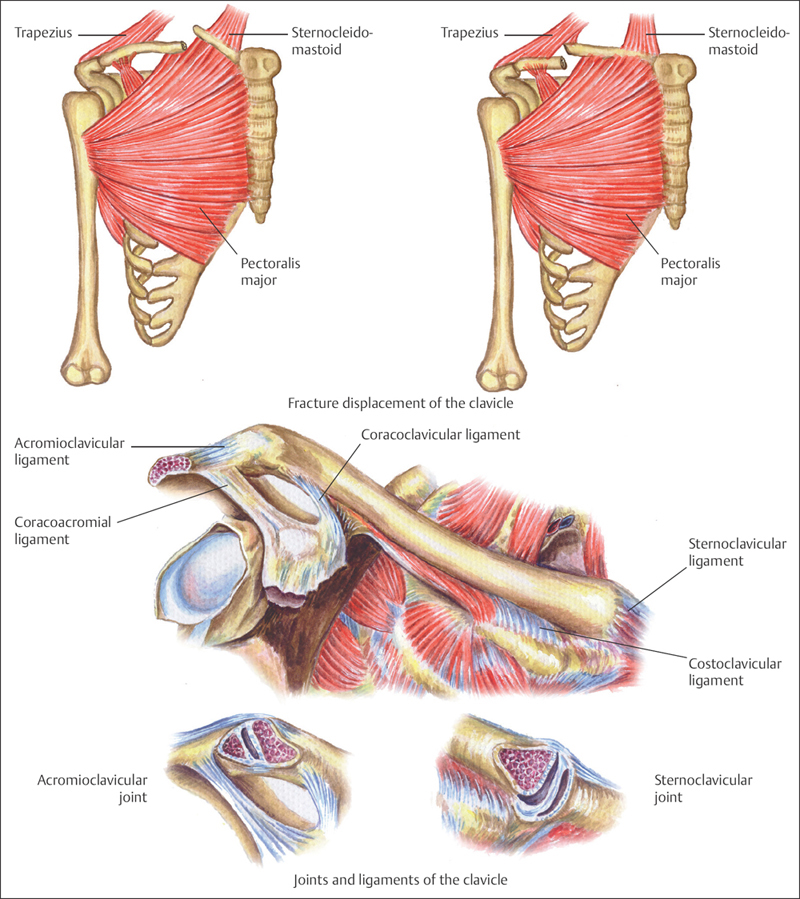

From an anatomic point of view, a few factors that result in the displacement of clavicle fractures can be summarized as follows: (1) the proximal fragment is typically displaced upward because of the pull of the sternocleidomastoid muscle; (2) although there may be some upward movement of the clavicle due to the pull of the trapezius muscle, the major displacement is caused by the downward pull of the upper extremity, since most patients would not be able to withstand the weight of the upper arm due to the pain; (3) however, if the upward pull of the trapezius muscle exceeds the weight of the upper arm, or patients are using a sling to support the arm, then the distal fragment may also be displaced upward; and (4) the pull of the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, and the latissimus dorsi draws the distal fragment medially (Plate 10.8).

Plate 10.8

The clavicle articulates medially with the clavicular notch of the manubrium sterni, forming the sternoclavicular joint, which is supported by the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular and interclavicular ligaments. The lateral end of the clavicle articulates with the acromion of the scapula, forming the acromioclavicular joint, which is stabilized by the acromioclavicular, coracoacromial, and coracoclavicular ligaments; these three ligaments form the coracoacromial arch. The coracoclavicular ligament consists of two fasciculi, the trapezoid and conoid ligament, which are attached between the coracoid process of the scapula and the underside of the clavicle; they primarily provide stabilization of the acromioclavicular joint and prevent superior dislocation of the shoulder joint (Plate 10.9).

Plate 10.9

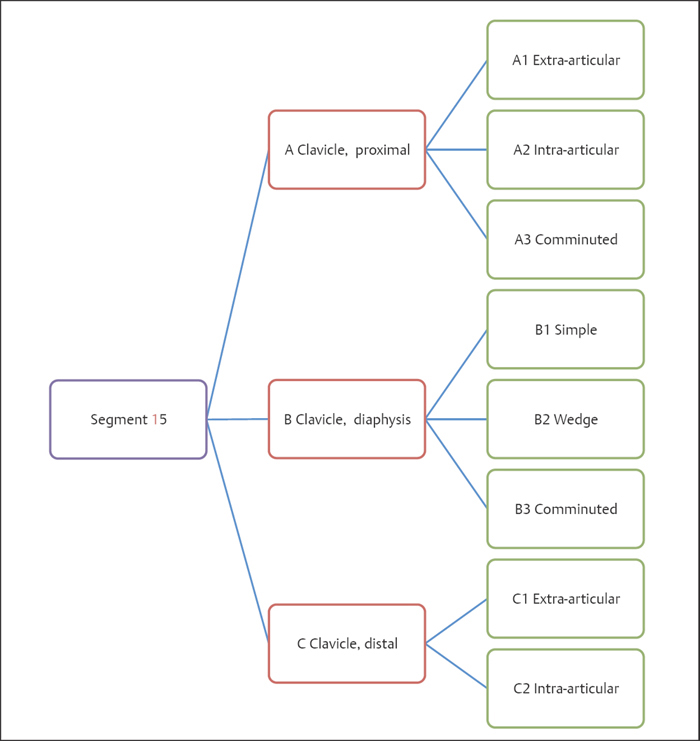

OTA Classification and Coding System for Clavicle Fractures

OTA Classification and Coding System for Clavicle Fractures

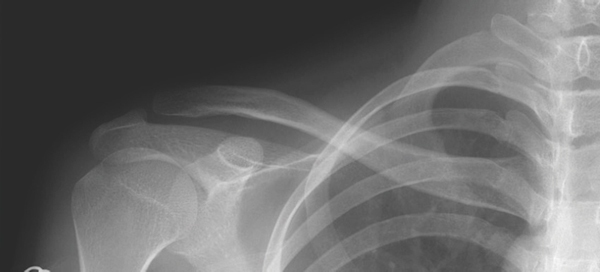

Based on OTA classification, the clavicle is coded as the number “15” for its anatomic location, and is divided into three segments: proximal, shaft, and distal according to the “Heim square” method. The OTA classification of clavicle fractures is as shown in Plate 10.10.

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Clavicle Fractures (Segment 15)

Clinical Epidemiologic Features of Clavicle Fractures (Segment 15)

A total of 1396 patients with 1404 clavicle fractures were treated at our trauma center over a 5-year period from 2003 to 2007. All cases were reviewed and statistically studied; the fractures accounted for 2.32% of all patients with fractures and 2.15% of all kinds of fractures, respectively. Among 1396 patients, there were 300 pediatric patients (300 clavicle fractures) and 1096 adult patients with 1104 clavicle fractures.

Plate 10.10

Epidemiologic features of clavicle fractures are as follows:

• more males than females

• more left-side than right-side fractures

• the high-risk age group is 41–50 years—the same age group for males, while for females the high-risk age group is 0–10 years

• the most common fracture type is type B.

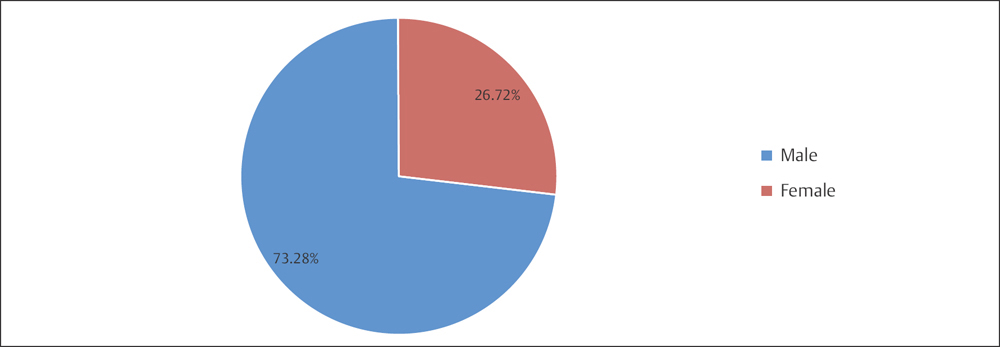

Clavicle Fractures by Sex

Clavicle Fractures by Sex

Table 10.7 Sex distribution of 1396 patients with clavicle fractures

| Sex | Number of patients | Percentage |

| Male | 1023 | 73.28 |

| Female | 373 | 26.72 |

| Total | 1396 | 100.00 |

Fig. 10.7 Sex distribution of 1396 patients with clavicle fractures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree