Flexor Hallucis Longus Tendon Augmentation for the Treatment of Insertional Achilles Tendinosis

William C. McGarvey

Thomas O. Clanton

DEFINITION

The term insertional Achilles tendinitis (IAT) is actually a misnomer. The condition is more typically a degenerative process, and the nomenclature should reflect this condition, more appropriately, as a tendinosis or tendinopathy.5,7,9,10,16

As the name suggests, IAT is identified by a painful condition at the tendinous insertion of the tendo Achilles (TA) on the posterior calcaneus.

It represents about 10% to 20% of all Achilles pathology.2

It is most commonly seen as an overuse injury in athletes, for example, runners and “push-off” athletes such as basketball or volleyball players, or in more sedentary patients as a degenerative process.

ANATOMY

The TA is the largest tendon in the body. Its chief function is plantarflexion of the foot and ankle.

It is viscoelastic and strong, elongating up to 15% under loads and bearing up to 10 times body weight in singlelegged stance during running.5,10

The Achilles insertion is a broad expanse that envelops the entire tuberosity of the os calcis and sends Sharpey fibers to the medial, lateral, and plantar borders of the bone.1

Immediately anterior to the TA lie the retrocalcaneal bursa and a variably sized posterolateral prominence of calcaneus, often known as Haglund deformity.

More anteriorly lies the deep posterior compartment musculature, which includes the flexor hallucis longus (FHL), and the neurovascular bundle, including the tibial nerve and vessels.

The FHL originates from the fibula and interosseous membrane, travelling obliquely and distally to pass under the sustentaculum tali, through a fibro-osseous tunnel, and on to the master knot of Henry to attach to the hallux.

PATHOGENESIS

Repetitive stress can lead to a combination of inflammatory and degenerative changes.

Degeneration or tendinosis occurs, as the already compromised vascularity of the tendon is further reduced by age and injury.9,10

Microscopic and macroscopic changes occur, leading to scarring and slow regeneration or repair.

Tenocytes are reduced in number and quality, contributing to poor repair potential.

Inflammatory changes are manifested as paratenonitis involving the investing layer surrounding the TA but not the tendon itself. This leads to thickening and adherence of the paratenon to the TA.

Additionally, the continuum of injury and inadequate repair capacity create a cycle of collagen and calcium deposition in an effort to stabilize the tendinous enthesis, leading to enlargement of the insertion site; generation of abundant, poor quality tissue; and irritation of the surrounding tissues, causing a painful thickening of the insertion of the TA.

NATURAL HISTORY

Untreated IAT has not been studied extensively. However, surgical findings and histologic analyses have provided some information.

Persistent IAT leads to continued pain and swelling of the retrocalcaneal heel.

A vicious cycle occurs in which further injury induces more attempts at repair and scar formation, leading to more irritation of surrounding tissues, decreased vascularity, and further microscopic injury.

The posterior heel is more difficult to accommodate in a shoe.

Range of motion is reduced, leading to increased susceptibility to injury with any activity that places the TA under strain.

Calcific debris is generated, both as reactive tissue response to injury and intratendinous hematoma formation as a result of injury. This compromises the viscoelasticity and, therefore, the integrity of the tendon, making it more apt to tear, either partially or completely.4,16

A less pliable, less resilient TA is the end product. Insertional avulsion or rupture may occur, presenting a difficult treatment dilemma.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients provide fairly accurate descriptions and complain of pain at the bone-tendon interface on the retrocalcaneal heel.

Pain may be worse after activity but gradually becomes more pervasive.

Athletes may note an increase in symptoms with increases in training intensity or duration or changes in surface or shoes.

Examination demonstrates tenderness directly posteriorly on the heel or, often, posterolaterally.

In advanced cases, thickening, nodularity, or hardening may be palpated.

Dorsiflexion of the ankle may be reduced compared with the contralateral leg.

Methods for examining the TA and its insertion include the following:

Direct palpation

The posterior heel and TA are inspected for visual or palpable swelling, tenderness, nodularity, or gapping, all of which are suggestive of diseased tendon.

Thompson test

With the patient prone, squeeze the calf at the gastrocnemius-soleus junction to elicit plantarflexion of the foot. Compare with the contralateral side. A positive test is identified when the excursion of the injured side is far less than its uninjured counterpart. This is evidence for complete rupture.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

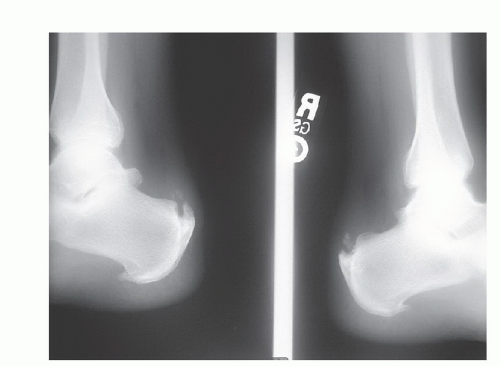

Radiographs

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a relatively inexpensive and accurate way to determine tendon quality, integrity, and function.

It has the advantage of being used dynamically to watch active tendon excursion, if so desired. It also may be used to follow the course of healing.

It is a highly user-dependent tool.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

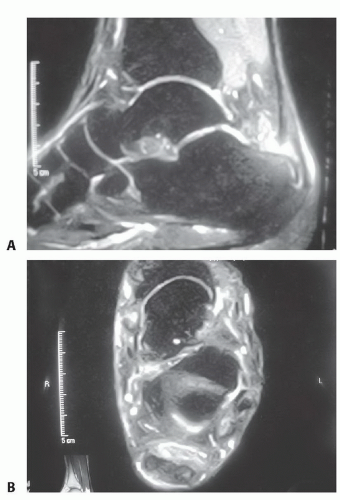

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) probably is the most comprehensive study available for investigation and evaluation of a damaged TA (FIG 2A,B).

This study gives the most accurate information regarding degree of TA involvement, quality of surrounding tissue, presence or absence of rupture, and other concomitant pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Retrocalcaneal bursitis

Haglund syndrome

Inflammatory arthritides

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies

Gout

Familial hyperlipidemia

Sarcoidosis

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

FIG 2 • MRI scan of IAT. In this T2 sequence, the degenerative areas of tendon are demonstrated by increased uptake within the substance of the tendon in the sagittal (A) and axial (B) planes.

Pharmacologically induced pathology

Fluoroquinolone use

Chronic corticosteroid use

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Success rates decline in the face of greater age at time of presentation, long-standing symptoms, and evidence of calcific tendinosis.9

Initial phases of treatment include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use, heel lifts, eccentric stretching, and shoe modifications to widen and soften the heel counter.

More advanced situations may call for formal orthoses to correct any biomechanical abnormality, night splinting to apply continual stretch to the TA, and therapy modalities such as ice, contrast baths, and iontophoresis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree