Flat Wedged Taper Femoral Components

Zachary Post

Richard H. Rothman

For many reasons, total hip arthroplasty is considered one of the most successful operations in orthopedic surgery and is extremely successful compared to many other surgical procedures of all types (1). This standard of success has largely been based upon the ability of hip replacement to alleviate pain, restore function, and allow patients to return to a more active lifestyle. From the successes of John Charnley to the sophisticated achievements of modern surgeons today, hip replacement has evidence of outcomes that any surgeon would envy.

Early hip replacement relied upon cement fixation to secure both the cup and the stem. This approach, fine tuned by Charnley, set the gold standard of pain relief and long-term function. However, not too many years after the universally celebrated success of cemented THA, problems began to develop. Aseptic loosening was seen on both the femoral and acetabular sides of the joint. What would eventually be known as osteolysis secondary to polyethylene wear was initially thought to be somehow related to the cement used in fixation. Bill Harris even coined the term “cement disease” to describe the phenomenon (2).

In spite of the concern that cement was somehow causing bone loss and leading to failure of THA, the operation continued to grow in popularity. Meticulous technique could, and did, lead to even better results. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with Charnley’s low friction, cemented hip arthroplasty shows an average 25-year survivorship of greater than 80% (3). However, the technique, particularly the mixing and use of the cement, was not easily reproduced by many surgeons. Cement technique initially required mixing in an open bowl and hand packing the cement in the canal with the stem. Several innovations were required to make good cementing more universally reproducible (4). The variability and inconsistency of cement was one of the factors that began the search for a more efficient and easily reproduced form of fixation for femoral components in THA.

A close look at Charnley’s patients reveals that many were older and less active. As the popularity and success of the operation spread, it became applied to a more diverse group of patients with disabling hip disease including the young and active. This younger group needed a hip replacement that could be functional for 20 years or longer under a wide variety of activity levels. Some studies have found that good outcomes diminished substantially when cemented THA was done in younger, more active patients (5,6). The concerns about “cement disease,” in combination with a need for more long-lasting fixation for younger patients ultimately led to the development of press-fit, biologically fixed stems widely used today. The tapered wedge design was introduced in the early 1980s and was widely available and used at our institution beginning in 1983. We have used this general design continuously since that time. Small innovations in the material as well as modifications of the design have improved the universal appeal of the stem. However, the concept of the tapered wedge has remained unchanged. The senior author (Richard H. Rothman) has implanted over 16,000 stems of this type and it continues to be used for nearly all patients undergoing THA at our institution.

Example Case

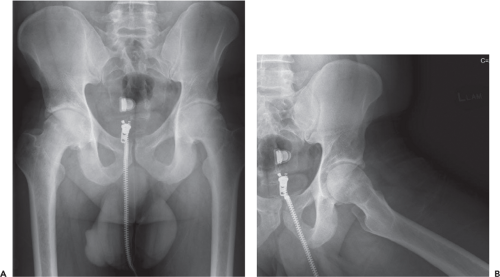

CT is a 42-year-old male who presented with several months of bilateral groin pain with the left being more severe than the right. The pain has begun to limit his ability to work and maintain his normal activities. His work as an athletic trainer requires him to maintain a high level of physical fitness and the hip pain has severely restricted that capacity. He has taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories for many months. Initially they helped with the pain, but they have become less effective over the last 2 to 3 months. He has no medical problems and does not take any other medication. On examination he has pain with hip motion, particularly forced internal rotation. He also has a fixed external rotation contracture. X-rays taken at the first office visit show bilateral joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and early osteophyte formation (Fig. 62.1A,B). On the initial visit he was diagnosed with degenerative joint disease of the hip. He was given a prescription for a different anti-inflammatory medication in hopes of improving his symptoms. He returned after 3 months without experiencing substantial pain relief.

CT has progressive arthritis of both hips and has failed conservative management. He would like to proceed with hip replacement to improve his ability to work and improve his quality of life. He represents a patient for whom dynamic bone ingrowth fixation would be an ideal solution.

Stem Design Characteristics

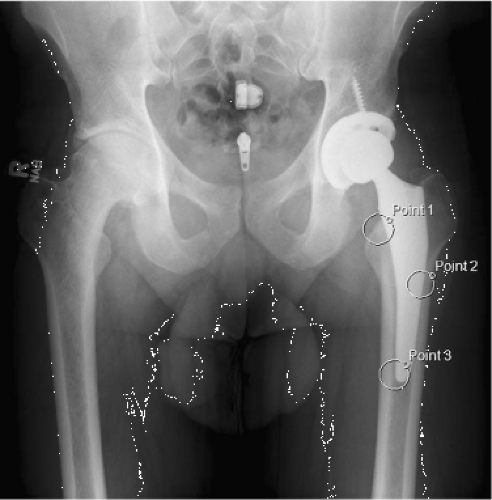

Long-term success and good outcomes for a press-fit THA stem are dependent on three main characteristics: stable fixation, minimization of stress shielding, and absence of thigh pain. Of the three basic types of press-fit stems, tapered wedge, anatomical, or cylindrical, the tapered wedge stem has several advantages. First is achievement of stable fixation. In general, the tapered wedge design is tapered in the medial to lateral dimension and then straight, or slightly tapered in the anterior to posterior dimension. The design includes a circumferential porous plasma spray coating that is restricted to the upper portion of the stem (Fig. 62.2A,B). The circumferential nature of the plasma spray seals the femoral canal from the effective joint space and minimizes osteolysis distal to the calcar. After initial implantation, this wedge design becomes tighter with additional pressure. As patients bear weight on the stem, the porous surface is more tightly compressed against the bone, encouraging bone ingrowth.

The tapered wedge also utilizes three-point fixation to achieve initial stability (Fig. 62.3). The tapered, porous-coated portion of the stem allows for tight engagement of the medial and lateral cortices while avoiding excess contact with the anterior and posterior cortices. Intimate contact is typically achieved with the medial calcar (point 1), and the lateral cortex (point 2). As the stem is impacted into place a tight fit is established between the bone and the proximal porous surface. The thinned, distal portion of the stem completing the three-point fixation (point 3), typically rests against the lateral and/or posterior cortex. The stem is thus

wedged into position where it is stable until bone ingrowth occurs. Typically, bone ingrowth is achieved during the first 6 to 10 weeks after implantation. The initial fixation is sufficiently stable to allow immediate weight bearing, without significant subsidence of the stem.

wedged into position where it is stable until bone ingrowth occurs. Typically, bone ingrowth is achieved during the first 6 to 10 weeks after implantation. The initial fixation is sufficiently stable to allow immediate weight bearing, without significant subsidence of the stem.

Figure 62.2. A: Frontal view of tapered wedge stem showing the proximal porous coating and tapered distal portion of the stem. B: Side view of tapered wedge stem showing the proximal porous coating. |

Figure 62.3. X-ray showing implanted tapered wedge stem and demonstrating the three-point fixation that secures the stem. |

Stress shielding is a phenomenon that results from excessive stress transfer by the implant resulting in decreased stress transfer to the host bone. The ultimate effect is to weaken the stress-shielded bone and potentially increase the probability of fracture. It has been described in cemented and press-fit stems (7,8). Some press-fit stem varieties, particularly anatomic designs made of cobalt-chrome, have shown increased rates of bone loss associated with stress shielding (9). The tapered wedge stem used in our practice is made of titanium, which has a modulus of elasticity more closely resembling that of bone. This results in a more flexible implant compared to cobalt-chrome. Decreased stiffness leads to a more natural proximal stress transfer by the host bone and diminished stress shielding (10). In addition, the tapered wedge stem ingrowth surface is restricted to the upper third of the implant. This design feature ensures weight transfer to the host bone in the region of the calcar and not to the diaphysis. Fully porous-coated press-fit stems, in contrast, transfer force all along the stem, including in the diaphyseal region of the femur, thereby leading to increased stress shielding of the proximal portion of the femur. One final design trait that helps minimize stress shielding is a tapered distal portion of the stem. This feature assists the stem to accommodate for decreased space in the diaphyseal region. Ideally, it also prevents engagement of the diaphyseal bone thereby preventing stress transfer in that region (Fig. 62.2A). Taken together, the design features of the tapered wedge stem minimize bone loss from stress shielding.

This incidence of thigh pain after uncemented THA has been reported to be as high as 40%, though the incidence of patients with severe pain is closer to 4% (11,12). There are several factors that contribute to thigh pain, but the design of the stem and material it is constructed from are well-known causes (12). The characteristics of a stem that lead to increased stress shielding are also associated with elevated levels of thigh pain. In general, the more rigid a stem, larger its size, and the more diaphyseal its fixation, the more likely it is to cause thigh pain. Here the tapered wedge design excels (12,13,14). The titanium construction in conjunction with a narrow anterior to posterior profile minimizes the rigidity of the implant. The coronal slot of removed material in the distal portion further decreases rigidity. Finally, restriction of the porous ingrowth surface to the proximal portion of the stem (and thereby the metaphyseal region of the bone) ensures stress transfer in a more anatomic fashion. The combined effect of these attributes is a very low incidence of thigh pain. Studies have found thigh pain associated with a tapered wedge design to generally be between 0% and 3% (15,16,17).

Indications and Contraindications

In our practice the indications for use of a tapered wedge stem in THA are simple. We essentially use this technique and style device for all patients who are candidates for elective THA. The only exception would be patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) and severe anteversion of the femoral neck. Our experience, over more than 30 years, has shown that a tapered wedge stem works well in nearly all other patients. There are published guidelines recommending caution when using a tapered wedge stem in patients with Dorr type C bone, rheumatoid arthritis, a femoral neck fracture, or patients who are elderly and sedentary (18). There are also many reports which demonstrate that the use of a tapered wedge in these settings is safe (10,17). The concern in patients with fragile bone is that a press-fit stem, impacted into position, is more likely to cause fracture. However, our experience has shown that careful technique makes the risk of fracture no greater than that associated with younger, healthier patients. There are situations where a cemented stem may be preferable. Patients, who have a history of metastatic disease requiring radiation treatment to the area where the femoral stem is to be implanted, potentially compromising bone ingrowth, should be considered for a cemented stem. However, in most institutions in the United States, ours included, the use of cement for femoral stem fixation is nearly nonexistent. It is so infrequent that the familiarity of most surgeons with good cement technique is extremely limited. This makes the outcome and long-term success of a cemented femoral stem, in any circumstance, more questionable.

There are situations where a press-fit stem is appropriate but a tapered wedge design may not be the ideal choice. Conversion from a cephalomedullary device used for treatment of hip fracture is one such situation. In fact, removal of any retained hardware in the region where the femoral stem is to be implanted can weaken the bone sufficiently to warrant additional support from a femoral prosthesis. It is these

situations where we consider use of a more fully coated, anatomic, or cylindrical stem for THA.

situations where we consider use of a more fully coated, anatomic, or cylindrical stem for THA.

Technique

Preoperative Planning

Perhaps the most important part of any surgical procedure, especially THA, is the preparation and planning done before making the incision. There are several aspects of THA that require a careful assessment of the x-rays and review of the characteristics of the planned implant to ensure a successful outcome. These include, but are not limited to; assessment of leg length, femoral offset, planning for location of the femoral neck cut, measurement and templating for size and position of the femoral and acetabular component, and evaluation for any potential hazards.

The first aspect of good preoperative planning involves a careful patient history. Details that affect the implantation of a tapered femoral component could include a history of steroid use, osteopenia or osteoporosis, or previous surgeries to the proximal femur. In general, any anomaly in the anticipated anatomy or patient factor that could weaken the proximal femoral bone or make the patient at greater risk of fracture should be discovered, recorded, and taken into consideration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree