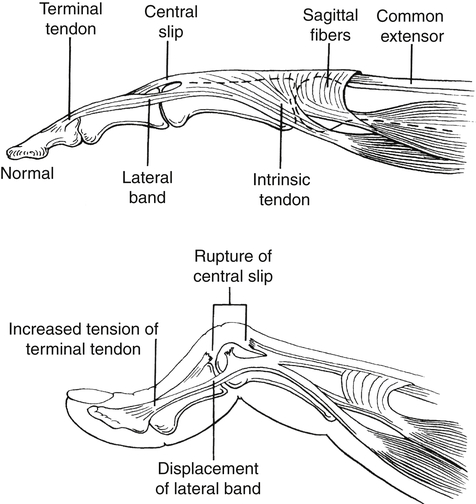

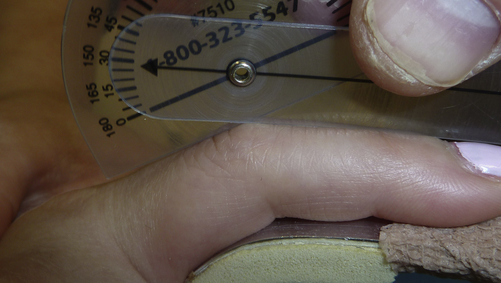

Injuries to the digits occur often in sports. Football players have a high incidence of proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint injuries. In these sports-related injuries, dorsal dislocations are more common than volar dislocations. Boutonniere deformities frequently occur in basketball players. Mallet injuries occur when the player’s fingertip strikes a helmet or ball.1 Therapists whose clients participate in sports can expect to see these common sprains and finger injuries as part of their caseload. A finger with drooping of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint is called a mallet finger (Fig. 29-1).2 Typically the DIP can be passively corrected to neutral, but the client is unable to actively extend it; this condition is called a DIP extensor lag. If the DIP joint cannot be passively extended to neutral, the condition is called a DIP flexion contracture. A DIP flexion contracture seldom is present early after injury; however, if the injury goes untreated, this problem may develop. The DIP joint of the finger is a ginglymus joint, or hinge joint. It is bicondylar (it has two condyles) and is similar to the PIP joint in its capsular ligaments. The terminal extensor tendon and terminal flexor tendon attach to the most proximal edge of the distal phalanx. This insertion contributes to the joint’s dynamic stability.3 A mallet injury frequently is caused by a blow to the fingertip with flexion force or by axial loading while the DIP is extended.4 The terminal tendon is avulsed. An avulsion fracture also may occur and should be ruled out. Laceration injuries (extensor zone I) are another cause of this deformity. Anterior/posterior (A/P) and true lateral x-rays typically are obtained. In addition, the PIP joint should be examined for possible injury.5 An orthosis is fabricated to hold the DIP joint in extension to slight hyperextension, depending on the physician’s preference. If hyperextension is recommended, the therapist should make sure the position of hyperextension is less than that which causes skin blanching. Exceeding tissue tolerance in DIP hyperextension can compromise circulation and nutrition to the healing tissues.6 Many types of DIP orthosis designs are available, and clients sometimes need more than one type (Fig. 29-2). They may also need an orthosis designated for showering; the client can carefully remove it after showering, according to the therapist’s instructions, and replace it with a dry orthosis. In this way, the skin is protected against maceration, which occurs if a wet splint is left on a digit. Casting also can be used when client compliance is a concern. If the DIP joint cannot be passively extended to neutral, serial adjustments of the orthosis may be done. If necessary, a small static progressive DIP extension orthosis can be used.7 Edema is treated as appropriate, and normal PIP active range of motion (AROM) with the DIP immobilized is promoted. Dorsal edema and tenderness over the DIP are common and can interfere with full DIP extension. After 6 weeks of continuous orthosis use, if no DIP extensor lag is present and the physician approves, gentle AROM can be started. A template may be provided (Fig. 29-3) to allow the patient to actively flex and extend the DIP joint from 0° to 25° for 1 week, and then adjusted to allow 35° of flexion the next week. If no lag is present, gentle composite AROM should then be permitted. The therapist should instruct the client to avoid forceful or quick grasping or forceful DIP flexion in the early phase of AROM therapy, and emphasis during exercise should be on DIP extension. It is very important to watch for DIP extensor lag. If DIP extensor lag occurs, the orthosis use and exercise progression must be adjusted. Passive motion to restore DIP flexion should not be used except in cases of extreme stiffness with limited progress with AROM only. Passive flexion will significantly increase the risk of extensor lag especially early in the rehabilitation process. Although the use of an orthosis is best initiated as soon as possible after injury, even a delayed regimen can be effective.8 Operative intervention can produce complications; therefore, non-operative solutions often are well worth the effort. If the mallet injury has associated large fracture fragments (greater than 30% of the joint surface) or the patient asserts that they cannot be compliant with orthosis use, surgery may be necessary. A variety of procedures can be performed to treat this injury.4,9,10 Surgical complications include the possibility of infection and nail deformities. With a boutonniere deformity, the finger postures in PIP flexion and DIP hyperextension (Fig. 29-6). The injury may be open or closed. With a closed injury, the boutonniere deformity may not develop immediately but may become noticeable within 2 or 3 weeks after the injury.8 The client may have a PIP extensor lag or, with an older injury, a PIP flexion contracture. This distinction affects the therapy choices. A boutonniere deformity involves disruption of the central slip of the extensor tendon, which normally inserts into the dorsal base of the middle phalanx. The disruption of the central slip causes the lateral bands to slip volar to the PIP joint axis of motion, creating flexor forces on the PIP joint.11 The imbalance results in hyperextension of the DIP joint.12 With this DIP posture, the oblique retinacular ligament (ORL) of Landsmeer, which is located at the dorsal DIP joint, is at risk of becoming tight. A pseudoboutonniere deformity is actually an injury to the PIP VP and is usually the result of a PIP hyperextension injury. A PIP extension thermoplastic orthosis or circumferential cast13 is typically used day and night for up to 6 weeks (Fig. 29-7). When ROM of the PIP is initiated, flexion to 30° to 45° is typically permitted and advanced 15° per week as long as no lag is present (Fig. 29-8). This is followed by 3 weeks of nighttime and intermittent daytime orthosis use. The orthosis is used during the time needed for the central slip to re-establish tissue continuity and for correction of the deformity.8 A variation from complete immobilization for 6 weeks is a short arc motion6 protocol that combines immobilization with intermittent controlled PIP motion to 30° to 40° of flexion during therapy sessions. After 3 weeks, the patient is provided a template for PIP ROM at home, and the template is advanced 10° to 15° per week if no lag is present. While the PIP is immobilized, it is very important that the therapist instruct the client in isolated DIP flexion exercises to recover normal length of the ORL. These exercises are done actively and passively in a gentle fashion (Fig. 29-9). The therapist should watch for normal MP AROM and should exercise this as needed. If exercise fails to recover DIP flexion with the PIP extended, ORL tightness (limited passive DIP flexion with the PIP extended) may need to be addressed with an orthosis. Various small, custom-made orthoses can be used for dynamic or static progressive DIP flexion with the PIP in full extension.14 Boutonniere deformity is caused by injury to zone III of the extensor tendons. Various surgical techniques are used to treat these injuries.8 The therapy protocol is determined in collaboration with the hand surgeon. The short arc of motion protocol for zone III extensor tendon repairs is appropriate if the client is considered a good candidate for this treatment (see Chapter 31).

Finger Sprains and Deformities

Mallet Finger

A fracture may also occur with this injury. (From American Society for Surgery of the Hand: The hand: examination and diagnosis, ed 2, Edinburgh, 1983, Churchill Livingstone.)

Anatomy

Diagnosis and Pathology

Non-Operative Treatment

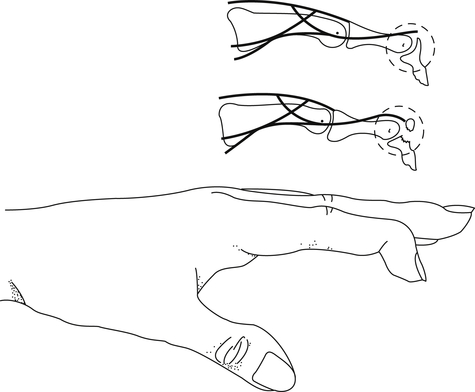

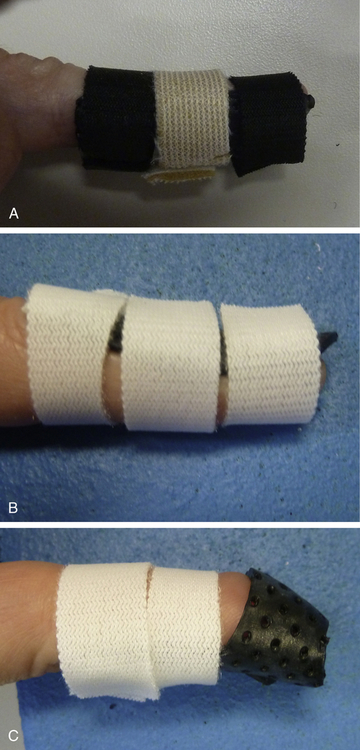

A, Custom thermoplastic volar. B, Dorsal. C, Combination dorsal/volar. (Reproduced with permission, Gary Solomon, MS, OTR/L, CHT.)

Operative Treatment

Boutonniere Deformity

Anatomy

Diagnosis and Pathology

Timelines and Healing

Non-Operative Treatment

Operative Treatment

Finger Sprains and Deformities