Lauren R. Eichenbaum

Geet Paul

Stephen Nickl

David Bressler

![]()

26: Fibromyalgia

![]()

PATIENT CARE

GOALS

Provide competent patient care that is team based, patient centered, compassionate, appropriate, and effective for the evaluation, treatment, education, and advocacy of fibromyalgia (FM) patients across the continuum of care and the promotion of health.

OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the key components of fibromyalgia and the assessment of FM, including history and physical examination.

2. Define the impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions of the patient with FM.

3. Identify the psychosocial and vocational implications of the patient with FM and strategies to address them.

4. Formulate an optimal rehabilitation program for the treatment and management of FM.

WHAT IS FIBROMYALGIA SYNDROME?

The etiology of the fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is not well understood. FMS is a common medical condition, which causes intermittent, chronic, widespread pain. It is more prevalent in women 20 to 60 years of age, affecting 0.5% to 5.0% of the population (1). It is exacerbated by poor sleep, activity, inactivity, and emotional stress (2). FMS continues to be a process in evolution, with symptoms being recognized since the 1700s. It was initially termed fibrositis, which was discarded when no inflammatory marker(s) could be identified. To date there are no specific tests for the diagnosis of FMS. In the 1990s the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) adapted diagnostic criteria that relied on the identification of “classical” tender points. In 2010, although still part of the physical examination, the identification of tender points was deemed no longer mandatory for a diagnosis of FMS. Instead, FMS is now considered a syndrome characterized by widespread pain due to the sensitization of the central nervous system. The cause(s) of this central maladaptation is multifactorial and has not been fully elucidated.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT PROPOSED CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF FIBROMYALGIA?

As previously noted, the ACR first developed the main diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia in 1990. At that time, patients included in the diagnosis presented with widespread pain for a minimum of 3 months and reported pain in at least 11 of 18 defined tender points. At that time, the exclusion of concomitant disease was not necessary.

In 2010, the ACR developed new guidelines for the diagnosis of FM. These guidelines no longer exclusively relied on the identification of select tender points (which were frequently performed incorrectly or not at all), but instead focused on a presentation of widespread pain with associated somatic and cognitive complaints (2,3,4). Three criteria were developed relating to the severity, the duration, and the exclusion of other diseases (Table 26.1).

WHAT IS CHRONIC WIDESPREAD PAIN?

Chronic widespread pain is characterized by pain for a minimum duration of 3 months in all four quadrants of the body, including the axial skeleton. The pain must be present on both sides of the body, both above and below the waistline (5). In addition, all other possible diseases must be ruled out (4).

WHAT IS THE WIDESPREAD PAIN INDEX?

The widespread pain index (WPI) broadens the tender point criteria to general areas of pain. It measures the presence of pain over the last week in 19 areas of the body thereby being scored from 0 to 19. The WPI includes the locations given in Table 26.2.

WHAT IS THE SYMPTOM SEVERITY SCALE?

The symptom severity (SS) scale score is a composite scale based on the severity of four specific symptoms (4). The first 3 symptoms are fatigue, waking unrefreshed, and cognitive symptoms. These symptoms are rated from 0 to 3 based on severity over the last week. The final category is the severity of somatic symptoms which include muscle pain, diarrhea, constipation, headache, dry mouth, insomnia, and depression. Somatic symptoms are rated from 0 to 3 (no symptoms, few, moderate, and a great deal of symptoms). The cumulative score for SS is between 0 and 12 (Table 26.3).

TABLE 26.1 2010 ACR Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia

1. Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity (SS) a. WPI ≥ 7 and SS ≥ 5 or b. WPI 3–6 and SS ≥ 9 2. Symptoms present for at least 3 months 3. Other possible disorders ruled out |

|

TABLE 26.2 WPI Tender Point Location

MIDLINE | RIGHT | LEFT |

Neck | Jaw | Jaw |

Chest | Shoulder girdle | Shoulder girdle |

Abdomen | Upper arm | Upper arm |

Upper back | Lower arm | Lower arm |

Lower back | Hip (buttock, trochanter) | Hip (buttock, trochanter) |

| Upper leg | Upper leg |

Lower leg | Lower leg |

WHAT ARE TENDER POINTS?

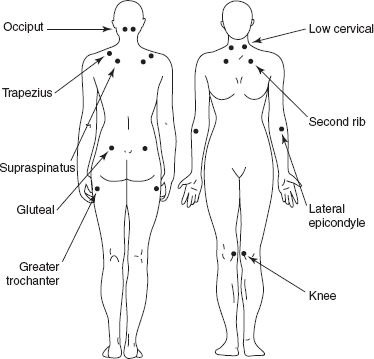

A tender point (Figure 26.1) is the presence of pain upon digital palpation of a muscle or tendon. The force with palpation should not exceed 4 kg/cm2 (approximately the amount of force that it takes to whiten your nail bed) (6). For a tender point to be positive, the patient must state that the palpation was painful. Note that a complaint of “tenderness” is not considered painful (5).

TABLE 26.3 Somatic Symptom Score

SYMPTOMS | GRADING | SOMATIC SYMPTOMS |

Fatigue | 0—Denies | 0—Denies |

Waking unrefreshed | 1 — Mild | 1—Few |

Cognitive symptoms | 2—Moderate | 2—Moderate |

| 3—Severe | 3—Great deal of symptoms |

FIGURE 26.1 Tender point locations according to 1990 ACR guidelines.

WHAT ARE THE PRIMARY SOMATIC AND COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH FMS?

SOMATIC | COGNITIVE |

IBS – Irritable Bowel Syndrome | Chronic fatigue |

Palpitations | Memory impairment (“fibrofog”) |

Subjective sensory deficits | Depression |

Headache |

|

WHAT ARE THE KEY PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS ASSOCIATED WITH FIBROMYALGIA SYNDROME?

According to Winfield, the population suffering from FM is likely to have had traumatic experiences in their childhood or other emotional stressors throughout their life (7). It is known that depression and emotional stress are strongly associated with FM (8). It is highly important that all patients diagnosed with FM be evaluated for depression or other psychiatric disorders. The disability and pain experienced in FM patients are associated with a poor quality of life (7). FM and depression have overlapping symptoms; therefore, the diagnosis and treatment of depression can often improve the somatic symptoms and quality of life of the patient with FM.

SAMPLE REHABILITATION PROGRAM

Goals: An education for the patient and family, modalities, aerobic exercise (AE), stretching, strengthening, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The program should be tailored to the needs of each individual. Warm water pool exercises have been shown to produce significant improvement (9). Aerobic training improves fatigue and depression, and participants were found to tolerate increased levels of pressure over their tender points (10). Aerobic training has also been shown to reduce muscle and cognitive fatigue, and to decrease symptoms of depression (11). A sample physical therapy (PT) prescription is presented in Table 26.4.

Alternative Treatment

There are many alternative treatments such as yoga, acupuncture, and meditation; however, Tai Chi is one of the most researched alternative exercise programs. Tai Chi is a low-intensity exercise, which utilizes a slow and constant shifting of body weight for balance training. This exercise has low impact on the spine and is void of abrupt movements, which can be a source of pain. It also incorporates deep breathing exercises for relaxation, making it a multidisciplinary treatment (12).

TABLE 26.4 Sample Physical Therapy Prescription

Diagnosis: Fibromyalgia |

Impairment: Symmetrical above and below waist tender points (11/18) |

Disability: Compromised activities of daily living |

Precautions: Standard |

Short-term goals: Reduction of tender point tenderness by 40%; increase of aerobic exercise tolerance to 10 minutes/session |

Long-term goals: Reduction of tender point tenderness by 75% to 80%; increase of aerobic exercise tolerance to 20 to 30 minutes/session |

Treatment: Tetanizing electrical stimulation + moist hot pack to area (s) of maximum tenderness for 20 minutes or massage for 20 minutes; progressive stretching/flexibility training to upper/lower extremities |

Cardiovascular conditioning with progressive aerobic training: Treadmill, bicycle, or recumbent bike (resistance free) as tolerated for 5 to 10 minutes at 50% to 60% of maximal heart rate (HR); increase as tolerated to progress to 20 to 30 minutes at 70% to 80% maximal HR |

Strength training: Isometric, isotonic, or isokinetics as tolerated |

Stretching and relaxation exercises |

Home exercise program (HEP) reflecting exercise protocol outlined earlier (HEP should be advanced to 20–30 minutes aerobic and flexibility training 5 to 6 times/week) |

Frequency: 2 to 3 times/week for 6 to 8 weeks |

At 6 to 8 weeks patient should be reevaluated and program adjusted to reflect progress to date |

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

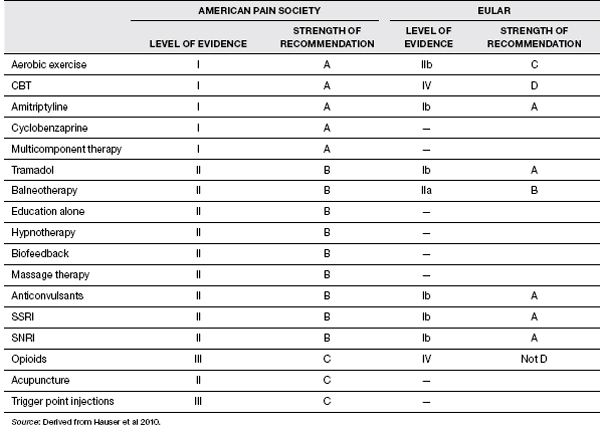

CBT is the integration of cognitive and behavioral therapies. Cognitive and behavioral factors play a large role in the symptomatic manifestations of FM. CBT provides psychological treatment that leads to modifications of dysfunctional thoughts and behavioral modifications. CBT was found to have efficacy in reducing depressed mood and in improving pain (13). The American Pain Society (APS) gave CBT a strong recommendation while the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) only gave CBT a weak recommendation.

MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

GOALS

Demonstrate knowledge of established and evolving biomedical, clinical, epidemiological, and sociobehavioral sciences pertaining to FM, as well as the application of this knowledge to guide holistic patient care treatment.

OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the epidemiology, anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology of FM.

2. Discuss the central sensitization theory.

3. Describe the role of neuroimaging in FMS.

3. Describe the neurotransmitters in pain signaling.

4. Evaluate both pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment of FMS.

According to the National Institutes of Health, FM has been diagnosed in over 5 million Americans who are over 18 years of age, the large majority of whom are women (14). Goldenberg and coauthors report that the disease is stratified in a ratio of 3.4% for women and 0.5% for men (15).

Studies have shown that there is a genetic predisposition toward the development of FMS (16). After osteoarthritis, FM is the second most common disorder seen by rheumatologists (15). Of interest, only 20% of the diagnosed population in the United States receives treatment (15). The medical costs of treating individuals suffering from FM increase with the severity of the disease, and can be an economic burden with annual expenditure ranging from $6,951 to $9,869 per patient (17).

Yunus (2001) introduced the term central sensitivity syndromes (CSS) to describe the group of syndromes that have significant overlap of symptoms with FM. These include chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, tension-type headache, migraine, temporomandibular disorder, myofascial pain syndrome, restless legs syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and more (18).

Yunus states that “Central sensitivity syndromes (CSS) comprise an overlapping and similar group of syndromes without structural pathology and are bound by the common mechanism of central sensitization (CS) that involves hyper excitement of the central neurons through various synaptic and neurotransmitter/neurochemical activities” (19).

While there are no specific diagnostic tests for FMS, an interesting electromyography (EMG)-based procedure has been proposed to establish the presence of “central sensitization” (20). An electrical correlate, which reflects central sensitization can be objectively demonstrated by using the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR). The test is performed as follows: the sural nerve that is purely sensory is slowly (start at 1 mA) stimulated over the lateral malleolus until a spinal flexion reflex contraction is recorded at the ipsilateral biceps femoris muscle tendon. The current threshold required to produce the initial contraction, has been shown to be consistently reduced, reflecting the hypersensitivity and central sensitization in FMS patient (20).

In FMS patients, the pain pathway is altered due to imbalance of several neurotransmitters resulting in centrally mediated augmentation of pain and sensory processes. Neurotransmitters that act to facilitate nociceptive processing are upregulated. This includes substance P, nerve growth factor, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Glutamate levels are also increased in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the brain. Glutamate is a key player responsible for the pain “wind-up” phenomenon, which results in greater hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain wind-up phenomenon is the perceived increase in pain intensity over time after repeated painful stimulation. Along with the upregulation of the ascending pathway there is decreased activity in the descending, antinociceptive pathway. There is a significant reduction in the CSF levels of metabolites of neurotransmitters that typically inhibit pain transmission, such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Opioid levels are also altered in FM patients. Opioid levels are found to be increased with decreased μ-opioid receptor availability. This can explain why opioid therapy may be ineffective in treatment of FM (21).

Neuroimaging studies have substantiated the growing body of evidence that FM is characterized by cortical or subcortical augmentation of pain processing. Functional MRI studies demonstrated, in FM patients, increased neuronal activation and cerebral blood flow at the pain processing centers of the brain at lower pain producing pressures compared to healthy individuals (22). Other neuroimaging studies have showed hypoperfusion of the striatum and thalamus, decreased dopamine binding in the striatum, and changes in the brain structures in the cingulated cortex, insular cortex, striatum, and thalamus. Results of these studies show that there are functional and morphological changes that occur in CNS structures involved in the pain pathway in patients with FM (23).

PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF FIBROMYALGIA

Historically, the most common agents used to treat FM were Tylenol, opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and cyclobenzaprine. But none of these medications or group of medications have been approved by the FDA to treat FM, and the studies that support their use are poorly designed. Currently there are only 3 drugs approved by the FDA for treatment of FM: pregabalin (Lyrica), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and milnacipran (Savella). These medications all serve as neuromodulating agents that alter the abnormal signaling in the spinal cord and brain of patients with FM.

The APS gave the highest level of recommendation to AE, CBT, amitriptyline, and multicomponent therapy (24). EULAR gave the highest level of recommendations to the pharmacologic treatments (tramadol, amitriptyline, fluoxetine, duloxetine, milnacipran, pregabalin, and more) (25). Note the APS recommendations are old, predating the FDA approval of pregabalin, duloxetine, and milnacipran (Table 26.5).

Tricyclic Antidepressants

TCAs, such as amitriptyline and cyclobenzaprine, have been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of pain as well as treating fatigue and poor sleep that is commonly associated with FM. TCAs increase the synaptic concentration of serotonin and nor-epinephrine by inhibiting the reuptake of these neuropeptides. However, due to their side-effect profile, including sedation, dry mouth, constipation, and cardiovascular issues, many patients are unable to tolerate these medications (26).

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that have been studied include fluoxetine, citalopram, and paroxetine. Controlled studies have shown mixed results. Mease (26) states that SSRIs are generally not as effective as TCAs and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), though they aid in the treatment of depression. APS gave SSRIs a moderate level of evidence, while EULAR gave it the highest level of evidence.

Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

SNRIs have been found to be most effective in treating FM and include venlafaxine (Effexor), duloxetine (Cymbalta), and milnacipran (Savella). Venlafaxine was the first of the SNRIs to be studied but the results were mixed (26). Duloxetine is the first of the SNRIs to be approved by the FDA for treatment of FM. In two separate double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies, duloxetine was found not only to decrease widespread pain but also to improve overall function, quality of life, and fatigue (27,28). Both studies demonstrated that the decrease in pain was direct, and not indirect through treatment of depression. The other SNRI to be approved by the FDA for FM is milnacipran (Savella). It has a higher ratio of norepinephrine to serotonin than the other SNRIs mentioned. Two separate but similarly designed double-blind RCT studies revealed that milnacipran significantly reduced pain and fatigue, and improved cognition (29,30). APS gave SNRIs a moderate level of evidence, while EULAR gave it the highest level of evidence.

Anticonvulsants

Gabapentin and pregabalin are both widely used for treating neuropathic pain. They bind to the alpha-2-delta protein associated with voltage-gated calcium channels and modulate calcium influx, resulting in the decreased release of Substance P and glutamate (26). Pregabalin was the first drug to be approved by the FDA for the treatment of FM. It was shown to be efficacious in the reduction of pain, disturbed sleep, and fatigue compared with placebo (32).

TABLE 26.5 Comparison of Evidence-Based Recommendations by APS and EULAR

Tramadol

Tramadol is a weak opioid with mild SSRI properties. Both APS and EULAR gave it a high level of recommendation. Bennett et al. in 2003 in a double-blind RCT demonstrated that tramadol combined with acetaminophen was effective in reducing pain in patients with FM (33).

NONPHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT OF FIBROMYALGIA

Exercise Program

Evidence supports the efficacy of AE for patients with FM. In a Cochrane review from 2008 (34), the authors concluded that moderate evidence supports AE having a positive effect on global well-being and physical function. In another meta-analysis, the Ottawa Panel (2008) found Grade A evidence that AE reduced pain and improved endurance and quality of life. AE should be performed at low intensity (50%–60% of maximal HR) to moderate (60%–80%) intensity, two to three times a week, and for at least 4 to 6 weeks in order to see a reduction of symptoms (35). It is important to remember that patients with FM are often overweight and with reduced cardiovascular fitness level. Overexertion can worsen pain. Start with low-intensity exercise, such as walking in place and aquatic therapy, and increase the intensity as tolerated (14). For a sedentary person who has moderate to severe FM, Jones and Liptan recommend the following progression: (a) breath, posture, and relaxation training; (b) flexibility; (c) strength and balance; and (d) aerobics (36). According to Busch et al. in a Cochrane review, strength-only and flexibility-only training remain incompletely evaluated as the studies are of either poor quality or completely lacking (34).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree