Femoral Neck Fractures: Hemiarthroplasty and Total Hip Arthroplasty

Ross Leighton

INTRODUCTION

Displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone provide unique challenges in treatment. Controversy continues regarding the optimal method of treatment (1). In displaced femoral neck fractures, most studies support replacement of the femoral head in older patients (2, 3, 4 and 5). Numerous authors have documented high rates of osteonecrosis, fixation failure, and nonunion when these fractures have been treated with internal fixation (6). Economic analyses indicate that the cost of treating such complications is immense (7, 8, 9 and 10). A long-term follow-up study of patients treated with open reduction of the displaced femoral neck fracture, evaluated 13 years after fracture fixation, found that the functional outcome deteriorated even among patients with a healed fracture and no osteonecrosis (11).

In contrast, arthroplasty allows rapid, safe mobilization of the patient without concern about fixation failure or fracture union (2, 3 and 4,12). Replacement arthroplasty is routinely done in patients most at risk for complications after internal fixation. These patients include elderly patients with compromised bone quality and fracture comminution. Over the last 10 years, prospective randomized trials have demonstrated the superiority of arthroplasty compared with internal fixation in this group of patients over the age of 60. The indications for hemiarthroplasty versus a total hip replacement are less clear (4,13).

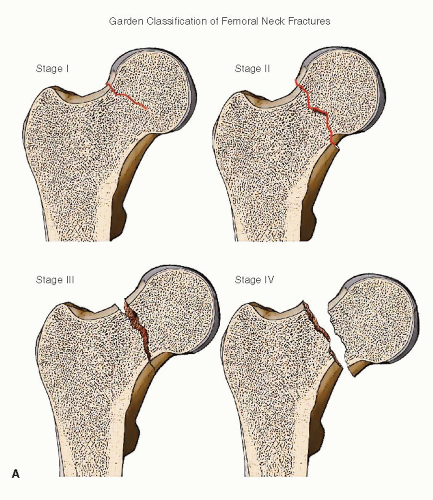

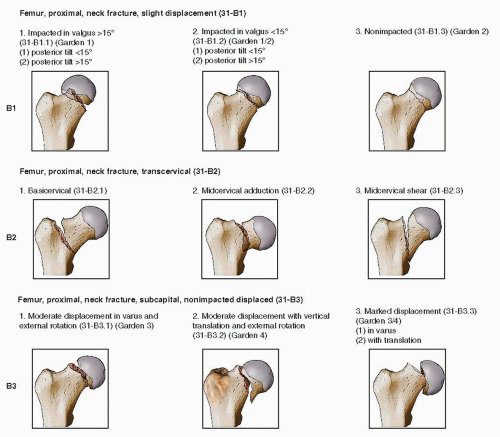

Despite substantial limitations, the Garden classification is probably the most frequently cited classification in North America. Garden I and II describe undisplaced fractures, while Garden III and IV are displaced femoral neck injuries. In the comprehensive AO/OTA classification scheme, femoral neck fractures are categorized as 31-B (Fig. 16.1A,B).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Internal Fixation

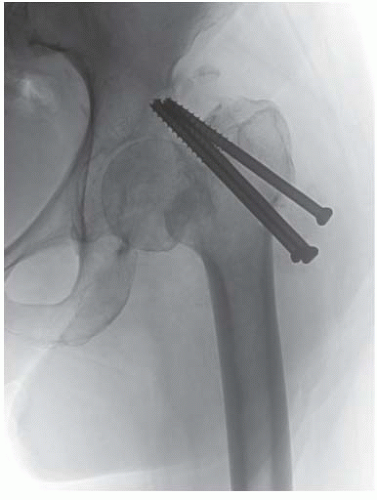

Internal fixation remains the treatment of choice for the majority of femoral neck fractures in patients <60 years of age. In patients >60 years of age, internal fixation using cannulated screws is reserved for nondisplaced Garden I and II fractures. The details and techniques of internal fixation are covered in Chapter 15.

Bipolar or Modular Hemiarthroplasty

The bipolar or modular hemiarthroplasty is the most commonly used implants to treat displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly. It can be used with a fixed head (unipolar) or bipolar head and provides a relatively easy conversion to a total hip arthroplasty (THA), if required in the future.

Strong indications for hemiarthroplasty are

Displaced femoral neck fracture in patients over 60 to 65 years of age without antecedent hip arthritis (Fig. 16.2).

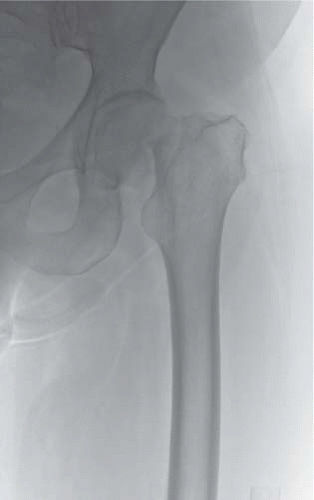

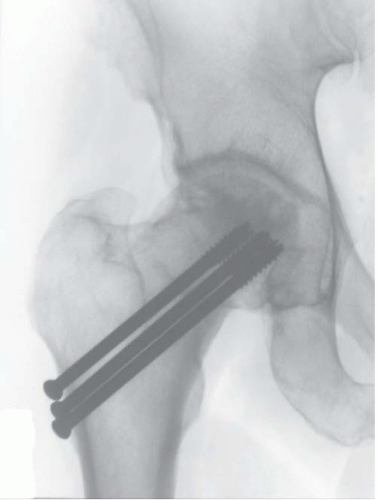

Patients >60 years of age with minimally displaced femoral neck fractures but whose bone is too poor for internal fixation (Fig. 16.3).

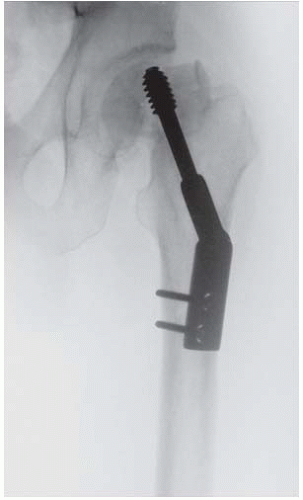

Failed internal fixation without associated acetabular damage (Fig. 16.4).

Comparisons between cemented bipolar and unipolar hemiarthroplasty have shown similar outcomes in terms of dislocation rates, postoperative pain, and recovery of ambulatory status (14, 15 and 16). Fluoroscopic evaluation after 1 year has shown that many bipolar prostheses placed for fractures act as a unipolar implant.

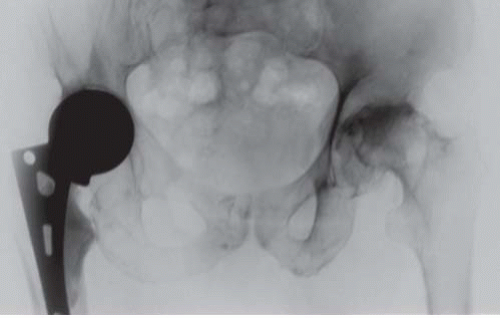

A cemented femoral stem is considered the standard treatment in the elderly osteopenic patient population (Fig. 16.5). The cement provides immediate stability and permits early weight bearing. The prevalence of postoperative acetabular pain or arthritis is uncommon with this method of treatment. Hemiarthroplasty should be modular to allow for changes in offset, length adjustment, and tensioning of the hip girdle muscles (17,18). The use of a Moore or Thompson prosthesis is of historical interest and is not recommended (Fig. 16.6). A modular head with a well-fitted cemented or occasionally uncemented femoral component is our preferred implant in elderly patients with displaced subcapital neck fractures (19).

Total Hip Arthroplasty

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an attractive treatment modality for selected elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures (Fig. 16.7). It is a technique known to most orthopedic surgeons. When used to treat hip arthritis, it has very predictable long-term results. Initial studies using total hip arthroplasty for fractures showed an increased rate of dislocation plus an increased amount of blood loss (20, 21 and 22). The initial cost is increased compared to a unipolar or bipolar arthroplasty; however, proponents of the technique (THA) argue that it may reduce the overall costs due to its theoretically improved long-term survival (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and 32). It is not indicated for most geriatric femoral neck fractures. The slightly higher dislocation rates combined with the difficulty in this frail patient population following the usual postoperative THA protocols has limited its use. However, in younger highly active patients (age 60 to 75 years) with little or no cognitive impairment and increased longevity of life, well-controlled studies have shown improved outcomes after THA (23,29).

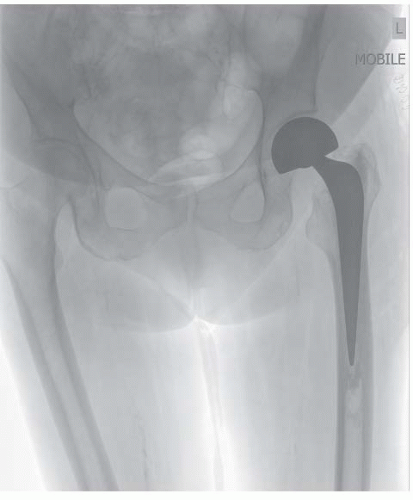

FIGURE 16.3 A minimally displaced femoral neck fracture in a patient with hemiplegia and poor bone stock. |

Strong indications for the use of THA in the management of acute femoral neck fractures in the elderly include (30,31):

Femoral neck fractures with associated hip joint disease.

Significant symptomatic contralateral hip disease.

Advanced osteoporosis with poor bone quality (Fig. 16.8).

Failure of internal fixation of a femoral neck fracture in patients over 60 years of age with acetabular damage (Fig. 16.9).

Failure of a hemiarthroplasty.

Relative Indications for Total Hip Arthroplasty include

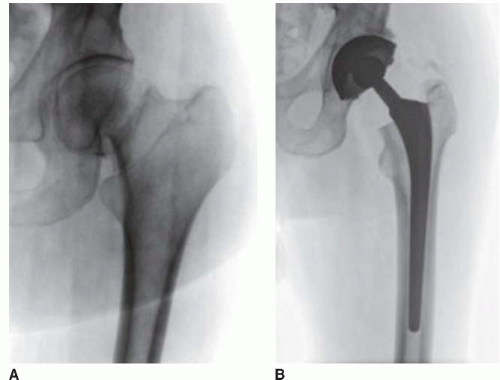

Healthy active patients over the age of 60 with a displaced femoral neck fracture (Fig. 16.10A,B).

Older cooperative patient with normal cognition and statistical survival rates >10 years.

Fractures secondary to metastatic disease with acetabular involvement.

In our center, an elderly patient with a displaced subcapital femoral neck fracture is most commonly treated with a cemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty (4). Uncemented stems are utilized in patients with excellent bone quality and canal diameters <16.5 mm. Uncemented stems are also preferred in patients with significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease (32) (approximately 3% to 5% of patients) (Fig. 16.11). In patients that are over the 60 years of age with osteoporotic bone that have a displaced femoral neck fracture, it is rare to regret doing a bipolar or modular unipolar hemiarthroplasty; however, it is very common to regret doing an ORIF in this particular group (Fig. 16.12).

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning is important to the success of the procedure. Leg length, offset, femoral head size, and the stability of the hip have to be carefully planned prior to surgery.

Preoperative templating of the contralateral side can be used as an alternate to templating the fractured hip and is strongly recommended.

History and Physical

A well-performed and documented history and physical should be performed on every patient. This includes determining important medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes (the Charlson comorbidity index). The patient’s current list of medication must be known as many elderly patients are on anticoagulants, antihypertensive medications, or corticosteroids, which may impact anesthesia or the timing of surgery. Most elderly patients with a hip fracture benefit from internal medicine and cardiology consultation, which have been shown to improve outcome and reduce hospital stay (33). Confirmation, with family members, of the drug history, medical and surgical history, and the presence of drug sensitivities and allergies can be very helpful in this population. The medical evaluation should proceed as quickly and safely as possible. Most patients should be ready for surgery within 24 hours of admission.

The vast majority of hip fractures in the elderly occur as a result of a mechanical ground-level fall. Physical examination reveals a tender and painful hip. The leg is shortened and externally rotated if the fracture is displaced. Range of motion of the hip is decreased or impossible secondary to pain. The peripheral pulses and neurologic examination should be carefully evaluated and documented.

FIGURE 16.11 An uncemented bipolar hemiarthroplasty utilized in a healthy 71-year-old female following a displaced femoral neck fracture. |

Imaging Studies

Radiographs should include an anteroposterior (AP) of the pelvis, an AP of the affected hip including 50% of the femoral shaft, and a lateral of the hip joint (shoot-through lateral). This allows the fracture to be classified as undisplaced Garden I or II or displaced Garden III or IV. A Clayton-Johnson lateral should be obtained, as opposed to a frog-leg lateral because it provides more information about acetabular version and possible posterior comminution in the femoral neck. High-quality imaging is essential both to understand the fracture morphology and allow for preoperative templating. As a general rule, templating is done on the uninjured hip to help reproduce the patient’s normal offset and height relative to the lesser trochanter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree