Febrile/Sick Athlete

Pierre Rouzier

INTRODUCTION

Caring for the sick athlete is both rewarding and challenging. In general your patient is healthier and more motivated to get well. However, because of training and competition needs, athletes or their coach may have an unrealistic expectation of when they can participate in their sport or training routine.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Exercise and the Immune System

Components of the immune system include the innate system and the acquired system. Innate components include the skin, mucous membranes, phagocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, cytokines, and complement factors. The acquired components of the immune system include T and B lymphocytes and plasma-secreted antibodies. Moderate exercise and intense, prolonged exercise can have different effects on the immune system. Persons who engage in regular moderate physical activity have been shown to have fewer respiratory illnesses than those who do not exercise.1,2 However, athletes with a vigorous training schedule or those who overtrain are at risk for more illness.3 Changes that occur with bouts of prolonged, intense exercise include a decrease in ciliary action, mucosal IgA levels, NK cell count and activity, T lymphocyte count, and T helper (CD4+) to T suppressor (CD8+) ratio. During this period an athlete may be more susceptible to infection. Endurance athletes may be at an increased risk for upper respiratory infections (URIs) during peak training and during the 2-week period after a marathon.4

College athletes in particular can be more susceptible to illness due to several factors, including high-density living (dormitories), exposure to sick teammates and classmates, less sleep than previously experienced, practice and competition in adverse environmental conditions, and possible overtraining.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

A 3-year analysis of college athletes’ visits to team physicians showed that athletes are more likely to seek medical care for an illness in comparison to injury.5 This chapter will look at common illnesses that athletes are likely to get and help give guidelines on return to play.

NARROWING THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The history and physical examination will be tailored to the affected systems. Appropriate diagnostic testing may be needed when indicated. Some general factors to consider in treating the sick athlete are as follows.

Should Athletes Train or Compete When They Are Sick?

Athletes should not train when they have a fever greater than 100.5 °F, significant malaise, myalgias, weakness, or shortness of breath or severe cough, or are dehydrated. Fever has been shown to compromise aerobic power, strength, endurance coordination, and concentration.6 Moderate exercise training during a rhinovirus URI does not appear to affect illness symptom severity or duration.7

The “neck check”8,9 has been a useful guideline in making a determination if athletes can participate. The basic premise is that if symptoms are above the neck (sore throat, nasal congestion, runny nose) and are not associated with symptoms below the neck (severe cough, malaise, gastrointestinal, or fever), then the athlete can have a trial of exercise at half intensity for 10 minutes, and if not worse, can continue as tolerated. When athletes resume training after recovery from an illness, it is important that they start at a moderate pace and gradually increase their intensity to the preillness level over 1 to 2 days of every training day missed.9,10

Nonmedical Factors

Unfortunately, there can be nonmedical factors contributing to or interfering with the care of the sick athlete. Elite-level athletes (professional and collegiate) as well as athletes in high school may feel that they must practice or compete despite their illness. They may feel pressure from their coaches or peers. Athletes may even underreport their illnesses to athletic trainers or team physicians because of these factors.

If athletes believe that you as a provider will return them to their sport as soon as is safely possible, they will be more willing to be compliant and honest about their symptoms.

If athletes believe that you as a provider will return them to their sport as soon as is safely possible, they will be more willing to be compliant and honest about their symptoms.

Reducing the Risk of Infection1

Keep other life stresses to a minimum

Eat a well-balanced diet

Avoid overtraining and chronic fatigue

Obtain adequate sleep

Avoid rapid weight loss

Avoid putting the hands to the eyes and nose

Before major competition avoid sick people and large crowds if possible

Get the influenza vaccine

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH UPPER RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS

Viral URIs are the most common medical ailments facing the athlete. The average adult has one to six episodes of the common cold each year, with 40% caused by rhinoviruses. In the United States, URIs are associated with major socioeconomic expense, with time lost from work and school, medical visits, and cost of medications. Though moderate exercise training may decrease the risk of getting URIs, heavy exercise may increase the risk of getting a URI. Despite this, athletes and exercise enthusiasts remain active during bouts of URI.11

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

URIs commonly present with complaints such as nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, cough, malaise, and fever. Physical examination is usually unremarkable except for potential rhinorrhea, pharyngeal erythema, and coarse upper respiratory breath sounds.

Pharyngitis and tonsillitis can be caused by group A streptococcus and viruses, including mononucleosis. The athlete will present with a sore throat, fever, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Tonsils will be enlarged and erythematous and may have exudate. A full description of mononucleosis and the athlete is reviewed below.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Lab tests are rarely needed for viral URIs unless influenza is suspected. In those situations, a rapid influenza test may be indicated. For suspected strep pharyngitis, a throat culture or rapid strep test should be obtained. Patients with clinical suspicion of mononucleosis should have a monospot or appropriate Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology checked, as noted in the section “Approach to the Athlete with Mononucleosis.”

TREATMENT

General Measures

The mainstay of treatment for viral URIs is symptomatic, including fluids, analgesia, decongestants, and cough suppressants, as needed.

Where relevant, care must be taken to document medical indication for decongestant use by athletes, as several are banned substances by various governing bodies, including pseudoephedrine.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Positive throat cultures or high clinical suspicion for group A strep pharyngitis should be treated with appropriate antibiotic.

Current recommendation for treatment of group A strep pharyngitis is penicillin V 500 mg two to three times per day for 10 days.12

For penicillin-allergic patients, treatment options include erythromycin or cephalosporin.

Prognosis/Return to Play

Current recommendations for uncomplicated viral URI are fever less than 100.5 °F, no significant malaise, myalgias, weakness, shortness of breath or severe cough, or signs of dehydration.

Affected individuals with streptococcus are usually not infectious after 24 hours of antibiotic treatment and may return to sport as tolerated if afebrile and fluid status normalized.

Complications/Indications for Referral

The most common complication from continued activity during a viral illness is simply feeling and performing poorly while sick. More significant cardiac complications, myocarditis and pericarditis, can occur as an aftermath of viral illnesses. Cardiotropic viruses, in particular Coxsackie B virus, have been implicated as the most common cause of myocarditis in the United States. Myocarditis is an inflammation of the myocardium accompanied by cellular necrosis. Athletes with myocarditis can present with chest pain or shortness of breath on exertion. They may present with congestive heart failure (CHF), syncope, or sudden death. Physical examination can show tachycardia, tachypnea, S4 gallop, edema, or other signs of CHF. An electrocardiogram (ECG) may show ST elevation and atrioventricular (AV) block. An echocardiogram can reveal left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, abnormal septal thickness, or diastolic dimensions.13

Athletes with pericarditis will frequently have an antecedent viral illness, pleuritic chest pain, hypotension, and a friction rub on clinical examination. Their ECG can show tachycardia, ST elevation, PR segment depression, and lowvoltage QRS complex. An echocardiogram should be performed and can show pericardial fluid in sac, decreased ejection fraction and global hypokinesis, and normal septal size and diastolic dimensions. Treatment can include anti-inflammatory medications, and in some cases, pericardiocentesis may need to be performed.14,15 Concern for myocarditis and pericarditis warrants a cardiology consultation.

APPROACH TO THE ATHLETE WITH OTITIS MEDIA

Common ear complaints in athletes include otitis media (OM) and otitis externa (OE). OM can be a common complication of a viral URI. Subclassification of OM includes acute OM, recurrent OM, OM with effusion, and chronic OM.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

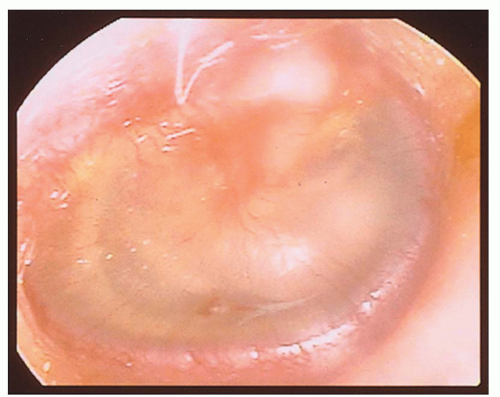

Symptoms of acute OM include ear pain, muffled hearing, and occasionally drainage. OM can be associated with a URI. Physical findings of OM include an erythematous, bulging tympanic membrane with decreased mobility (Fig. 7.1).

TESTING

Testing is usually not required in acute cases. Cases of chronic serous OM may require audiology evaluation to assess for hearing loss.

FIG. 7.1. Otits media.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|