Abstract

Fear of falling may be as debilitating as the fall itself, leading to a restriction in activities and even a loss of autonomy.

Objectives

The main objective was to evaluate the prevalence of the fear of falling among elderly fallers. The secondary objectives were to determine the factors associated with the fear of falling and evaluate the impact of this fear on the activity “getting out of the house”.

Patients and method

Prospective study conducted between 1995 and 2006 in which fallers and patients at high risk for falling were seen at baseline by the multidisciplinary falls consultation team (including a geriatrician, a neurologist and a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician) and then, again 6 month later, by the same geriatrician. The fear of falling was evaluated with a yes/no question: “are you afraid of falling?”.

Results

Out of 635 patients with a mean age of 80.6 years, 502 patients (78%) expressed a fear of falling. Patients with fear of falling were not older than those who did not report this fear, but the former were mostly women ( P < 0,001), who experienced more falls in the 6 months preceding the consultation ( P = 0.01), reported more frequently a long period of time spent on the floor after a fall ( P < 0.001), had more balance disorders ( P = 0.002) and finally, were using more frequently a walking technical aid ( P = 0.02). Patients with fear of falling were not going out alone as much as the fearless group (31% vs 53%, P < 0.0001). Eighty-two percent of patients in the fearful group admitted to avoiding going out because they were afraid of falling.

Conclusion

The strong prevalence of the fear of falling observed in this population and its consequences in terms of restricted activities justifies systematically screening for it in fallers or patients at risk for falling.

Résumé

La peur de tomber peut être aussi invalidante que la chute elle-même, pouvant entraîner une restriction d’activité, voire une perte d’autonomie.

Objectifs

L’objectif principal était de déterminer la prévalence de la peur de tomber dans une population de sujets âgés chuteurs, appréciée par une échelle d’évaluation dichotomique « Avez-vous peur de chuter ? Oui/Non » ; les objectifs secondaires étaient de déterminer les facteurs associés à la peur de tomber ; et de préciser le retentissement de la peur de tomber sur l’activité « sortir de chez soi ».

Patients et méthodes

Étude prospective des patients s’étant présentés consécutivement à la consultation multidisciplinaire de la chute (un gériatre, un neurologue, un médecin rééducateur) du centre hospitalier regional et universitaire (CHRU) de Lille (France) entre 1995 et 2006.

Résultats

Sur 635 patients d’âge moyen de 80,6 ans, 502 patients alléguaient une peur de tomber. Les patients reconnaissant une peur de tomber n’étaient pas plus âgés que ceux n’exprimant pas cette peur, mais étaient plus souvent des femmes ( p < 0,001), avaient présenté plus de chutes dans les six mois précédant la consultation ( p = 0,01), rapportaient plus fréquemment une chute avec un séjour prolongé au sol ( p < 0,001), présentaient plus souvent des troubles de l’équilibre ( p = 0,002) et utilisaient plus souvent une aide technique de marche ( p = 0,02). Les patients exprimant une peur de chuter sortaient moins souvent seul de chez eux (31 % vs 53 %, p < 0,0001). Quatre-vingt-deux pour cent des patients ayant peur de tomber admettaient éviter de sortir de peur de tomber.

Conclusion

La forte prévalence de la peur de tomber observée ici et les conséquences de celle-ci en termes de restriction d’activité justifient sa recherche systématique chez un patient chuteur ou à risque de chute.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Falls are one of 10 leading causes of death for the elderly. After the age of 70, falls even are the primary leading cause of accidental death. In fact, numbers show that a third of elderly persons living at home and half of institutionalized elderly persons fall every year. The fear of falling has been reported as a very common feature in elderly persons, regardless of previous falls ; it has usually been associated to a restriction of activities in this population . This fear has also been identified as a risk factor for falls, especially as part of a post-fall syndrome or psychomotor disadaptation syndrome (PDS) .

Other terms have been used to define this fear of falling such as feeling of insecurity, apprehension, anxiety, avoiding some specific activities . There are as many tools to evaluate the fear of falling as there are definitions of this fear (e.g. more than 20) .

The great variability of these scales and the subsequent multiple definitions of this fear of falling result in disparate prevalence numbers reported for this phenomenon . The restriction of activities in fallers has been perfectly described in the literature . It can have a protective impact on the short term, by limiting the risk of a new fall yet it ends up having a negative impact on the long term by reducing the physical abilities of geriatric patients. The activity restriction linked to the fear of falling has been correlated also to the following elements: a traumatizing fall in the past year, existence of comorbidities, depressive symptoms and decreased physical capacities . This fear of falling can explain the restriction of some activities in this population, such as bending down, trying to get something above their head, not going out of the house as much, especially outings associated to social activities (e.g. religious services, social activity clubs, visiting friends or family) .

The main objective of our study was to determine the prevalence of this fear of falling in patients seen in the framework of our multidisciplinary falls consultation at the University Hospital of Lille, France (CHRU) and to achieve this goal we used a yes/no questions evaluation scale (e.g. “are you afraid of falling? Yes/No”). The secondary objectives were to determine factors associated with the fear of falling and to assess the impact of this fear on the “going out” activity.

1.2

Patients and methods

The multidisciplinary falls consultation was created at the Lille University Hospital in 1995 as part of Les Bateliers Geriatrics Hospital. All patients seen at this multidisciplinary falls consultation at the Lille Hospital between 1995 and 2006 were included in this study. Each patient was successively examined by a geriatrician, a neurologist and a physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) physician . The initial examination was analytic, functional and environmental. The variables were collected with a standardized file and included sociodemographic data (age, sex, type of housing, living alone or not, educational level, and occupation), medical history and ongoing medical treatments. Weight and height were measured to calculate the patients’ body mass index (BMI). The autonomy was evaluated with the Activity of Daily Living (ADL) Scale . Cognitive functions were assessed with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) . Patients were considered as having dementia when they had a MMSE ≤ 24, had previously been diagnosed with dementia before the consultation or had been diagnosed within 6 months post-consultation (aside from their MMSE score). The circumstances of the falls, number of falls in the 6 months before the consultation and maximum period of time spent on the floor after a fall were also compiled. The interview conducted with the patients and their caregivers or loved ones helped identify behavioral and environmental factors. The physical examination refined the individual factors promoting or triggering these falls while systematically screening for gait and balance disorders. Balance disorders were defined as patients loosing balance in double stance with eyes open or close, or patients having difficulties to adapt posture, especially when pushing lightly on sternum with palm. Data from the clinical examination and a precise gait description written by each of the physician having examined the patient allowed us to classify the gait disorders in a retrospective manner for each patient according to the classification proposed by Alexander and Goldberg in 2005 . The great prevalence of neurological pathologies in our patients completely justified the participation of a neurologist . Four questions evaluated the fear of falling ( Table 1 ).

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Are you afraid of falling? | ||

| Inside of your home? | ||

| Outside of your home? | ||

| Do you avoid going out for fear of falling? | ||

After the multidisciplinary falls consultation, the geriatrician wrote a letter to the patient’s family physician with a copy to the patient if he/she requested one. The letter ended with a list of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors and practical therapeutic proposals. The prescription for physiotherapy sessions, when necessary, was written up by the PM&R physician and sent at the same time as the previous letter to the family physician. The application of these practical measures was the responsibility of the patient, his or her family and family physician. The patients were seen 6 months later during a follow-up consultation with the geriatrician.

The first part of our work consisted in describing the characteristics of this population. For the second part of this study, we identified the patients having answered yes to the question “are you afraid of falling” ( Table 1 ).

Then, we analyzed the existence of an association between the fear of falling, restriction of outing activities linked to this apprehension and the characteristics of the population.

The statistical analyses were computed with the SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC 25513). The Student’s t -test was used to compare two groups according to a numeric variable. To compare more than two groups according to one variable we used a Fisher’s exact test for ANOVA (analysis of variance). We used the Pearson’s correlation coefficient to search for the correlation between two numeric variables. The correlation between two variables was deemed significant when P ≤ 0.05. Two multivariate logistic regression models were computed: one to analyze the fear of falling and the other one to analyze the action of going out alone. In order to do this, we introduced into a step-by-step multivariate logistic regression model the variables that had a significance level ≤ 0.2 along with the variable to be analyzed. The results were presented as odds ratio with a confidence interval of 95%.

1.3

Results

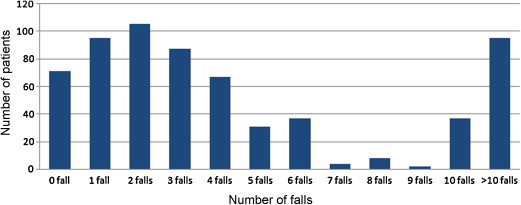

Six hundred and forty_one patients were seen in the multidisciplinary falls consultation between 1995 and 2006. Eighty-nine percent of these patients reported at least one fall in the past 6 months ( Fig. 1 ). It was possible to analyze the fear of falling in 635 patients, yielding a prevalence of 79% (502 patients). The characteristics of these patients were reported in Table 2 .

| Characteristics of the population | Fear of falling ( n = 502) | No fear of falling ( n = 133) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean age (years) | 80.6 | 80.6 | NS |

| Gender (F/M) | 382/120 = 2.7/1 | 81/52 = 1.6/1 | 0.0005 |

| Psychosocial data | |||

| High level of education | 178 ( n’ = 463) (38%) | 58 ( n’ = 125) (46%) | NS |

| Patient living in an institution | 122 ( n’ = 499) (24%) | 34 ( n’ = 131) (26%) | NS |

| Patient living alone | 291 ( n’ = 501) (58%) | 70 ( n’ = 132) (53%) | NS |

| ADL (mean/median) | 4.9/5.5 | 5.1/5.5 | NS |

| Using a walking aid | 215 ( n’ = 484) (44%) | 41 ( n’ = 124) (33%) | 0.02 |

| Medical data | |||

| Mean BMI | |||

| Men | 26 | 25.3 | NS |

| Women | 24.9 | 24.4 | NS |

| High blood pressure | 280 (56%) | 60 (45%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 89 (18%) | 18 (14%) | NS |

| Dementia | 233 (46%) | 64 (48%) | NS |

| History of stroke | 72 ( n’ = 501) (14%) | 17 (13%) | NS |

| Parkinsonian syndrome | 45 (9%) | 10 (8%) | NS |

| Depression | 112 (22%) | 24 (18%) | NS |

| History of fractures | 202 (40%) | 54 (41%) | NS |

| Number of prescription drugs | 349 (70%) | 91 (68%) | NS |

| Taking at least 1 psychotropic drug | 281 (56%) | 71 (53%) | NS |

| Under antidepressant treatment | 121 (24%) | 21 (16%) | 0.04 |

| Fall risk factors | |||

| Number of falls in the past 6 months (median) | 3 | 2 | 0.01 |

| None | 49 (10%) | 23 (17%) | 0.02 |

| 1 fall | 71 (14%) | 24 (18%) | NS |

| ≥ 2 falls | 381 (76%) | 86 (65%) | 0.01 |

| Lying on the floor ≥ 1 hour | 168 ( n’ = 486) (34%) | 14 ( n’ = 128) (11%) | < 0.0001 |

| Get up and go > 20 seconds | 236 ( n’ = 388) (61%) | 48 ( n’ = 99) (48%) | 0.03 |

| At least one environmental factor | 368 ( n’ = 461) (80%) | 86 ( n’ = 123) (70%) | 0.03 |

| Proprioceptive disorder | 317 ( n’ = 443) (72%) | 69 ( n’ = 104) (66%) | NS |

| Gait disorder | 417 ( n’ = 479) (87%) | 104 ( n’ = 122) (85%) | NS |

| Balance disorder | 333 ( n’ = 480) (69%) | 66 ( n’ = 121) (55%) | 0.0002 |

| Visual impairment | 215 ( n’ = 484) (44%) | 53 ( n’ = 124) (43%) | NS |

| Follow-up at 6 months | |||

| Recurrence of falls | 129 ( n’ = 341) (38%) | 30 ( n’ = 87) (34%) | NS |

| Deaths | 18 ( n’ = 485) (4%) | 7 ( n’ = 132) (5%) | NS |

| Institutionnalization | 25 ( n’ = 328) (8%) | 9 ( n’ = 85) (11%) | NS |

This fear of falling was reported by more women than men ( P < 0.0005). A history of falls and the number of falls in the 6 months before baseline consultation were significantly associated with the fear of falling. In patients afraid of falling, 34% had spent a long time on the floor after a fall (over 1 hour) versus 11% of patients not without fear of falling ( P < 0.0001). A balance disorder was more often found in patients with fear of falling ( P = 0.03). In multivariate analysis, being a woman and having spent a long time on the floor seemed to be independent risk factors from the fear of falling itself ( Table 3 ). The use of a technical aid for walking was significantly more frequent in the group of patients afraid of falling ( P = 0.02). No significant difference was found between both groups regarding depression, but a significant difference was found for taking an antidepressant treatment ( Table 3 ).

| Odds ratio (confidence interval 95%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) |

| Time spent on the floor > 1 hour | 4.02 (1.99–8.11) |

| Going out alone | 0.56 (0.35–0.88) |

| Taking an antidepressant treatment | 2.39 (1.22–4.65) |

| Balance disorders | 1.58 (0.99–2.52) |

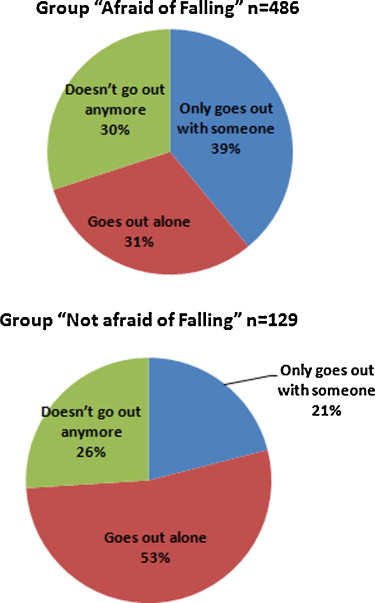

Among the 502 patients who reported a fear of falling, 374 (75%) admitted to being afraid of falling inside their homes and 493 (98%) admitted to being afraid of falling outside their homes. Among the 625 patients (data missing for 10 of the 635 patients), 438 (70%) said they did go out of their homes, but only 218 patients (35%) reported going out alone for a walk outside their homes. More than one third of patients seen during this consultation ( n = 184) were not going outside their homes any longer. Our data showed a link between this fear of falling and the ability of patients to go out of their homes alone (odds ratio = 0.52 [0.30–0.89]), independently of the existence of gait disorders ( Table 4 ). One hundred fifty patients (31%) who were afraid of falling reported going out alone ( Fig. 2 ), versus 68 patients (53%) in the group not afraid of falling ( P < 0.0001). Eighty-two percent of patients afraid of falling admitted they avoided going out their homes because of their fear of falling. At the 6-month follow-up visit, we did not highlight any significant difference in terms of recurrent falls, patients placed in an institutionalized setting or deaths between the group afraid of falling and the group not afraid of falling ( Table 2 ).

| Odds ratio (confidence interval 95%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 2.01 (1.17–3.47) |

| Patient living alone | 2.19 (1.37–3.52) |

| Patient living in an institution | 0.49 (0.27–0.88) |

| Number of falls | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) |

| Time spent on the floor > 1 hour | 0.39 (0.23–0.67) |

| History of fracture | 0.66 (0.42–1.04) |

| Depression | 0.53 (0.30–0.93) |

| Dementia | 0.37 (0.23–0.58) |

| Using a technical aid for walking | 0.36 (0.22–0.57) |

| Fear of falling | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) |

| Gait disorders | 0.27 (0.14–0.50) |

1.4

Discussion

The main results of this study showed a high prevalence of the fear of falling in the elderly population (79%), with predominant apprehension for going outside their homes (98% of these 79%). This fear of falling was significantly associated to limited outings when the patients were not accompanied by a third person. The prevalence of the fear of falling in elderly patients varied between 20 and 85% according to the studies . Our reported prevalence rate is in the upper range; this is probably due to patients’ recruitment in the multidisciplinary falls consultation. In fact, most patients seen in this consultation have fallen several times; the proper therapeutic care becomes difficult for our colleagues referring these patients to us. These patients admitting to being afraid of falling were in majority women, agreeing with the results from the literature . When in the literature, age was also reported as a risk factor for fear of falling ; we did not observe any difference by age groups in our population. This could be explained by the advanced age of most patients evaluated in the multidisciplinary falls consultation and the very small number of younger patients. For Tinetti et al., the proportion of patients afraid of falling increased according to the number and severity of the falls they had experienced . Many older patients restricted their activities in the 2 years following a severe fall (fracture, brain trauma), but the correlation was not found 5 years after the fall . Our results indicate that in the group of patients afraid of falling, significantly more patients had reported having spent more than 1 hour on the floor after a fall. This notion was also reported in several published works . A long time spent on the floor is often experienced by elderly patients as a deep identity wound, even more than the fall itself, because it highlights their lost functional independence and leads to self-esteem loss.

For these patients, this can partly explain the fear of going out of their homes after a fall. Independently from a long time spent on the floor or an inability to get up, the restriction of activities right after a fall, can often be considered like a protection towards risks of recurrent falls, thus unveiling a “reasonable” fear of falling taking into account the individual and environmental factors that could have promoted the fall. Unfortunately, on the long term, this restriction of activities was often associated to a decrease in physical and intellectual abilities, increasing the risk of falls .

Just like a long time spent on the floor, a fracture is a traumatizing event. Yet, we did not observe an association between a history of fracture post-fall and the fear of falling. This could probably be explained by the fact that the item “history of fracture” takes into account all fractures when the patient’s fell from his or her own height during adulthood. More generally, the fear of falling has been reported in association to musculoskeletal diseases (arthritis, osteoporosis and other types of joint disorders) . In several studies, depression was strongly correlated to the fear of falling, sometimes as its cause and other times as a consequence . It is also a factor frequently associated with the restricted mobility of elderly patients. We did not observe any association in our study, yet this could be explained by the lack of a specific evaluation for depression using validated scales. The term “depression” we used in our work, grouped together patients who reported a history of depression (even an old one) at baseline and patients who were considered depressive by the physicians in charge of the falls consultation. However, taking an antidepressant at the time of the consultation, a reliable yet imperfect witness of a recent depressive episode, was significantly associated to the fear of falling. Of course we could not exclude the notion that the prescription of this antidepressant treatment could be proposed to fallers as a solution to their fear of falling.

The fear of going outside is quite common in elder patients, associated to increased difficulties for getting around for distances less than 2 km . Our data also show a change in the way patients go out of their homes – they go out more when accompanied, related to the fear of falling, without totally suppressing the going out activity. This result should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of data regarding the frequency of these outings (the data could not be analyzed because they were not available for all patients) and the notion of life space. We can understand that the restriction of activity linked to the fear of falling could be different for patients driving their car and for patients with a life space restricted to 100 m beyond their doorstep. Since our study, this element has been collected using the French version of the Life Space Assessment .

The lack of significant difference between the groups “fear of falling” and “no fear of falling” in the population of patients not going outside their homes is quite surprising. The fear of falling is probably one of the factors explaining this home confinement in the first case. Disability stems from a discrepancy between a person’s capacities and the environmental requirements . Thus, a person’s state of health and environmental characteristics could also restrict his or her outside activities. For Rantakoko et al., the fear of going outside could also be the consequence of a discrepancy between these environmental requirements and the capacities of an individual .

Even though they were not part of this study, some environmental factors were reported as associated to a restriction of outings outside the home; such as poor road state (holes, uneven grounds), noisy road traffic and hills. Evaluating the fear of falling with a yes/no questionnaire does not allow for a gradual evaluation of this fear. Several scales can be used by physicians to refine this evaluation of the fear of falling, mainly to identify the activities generating this apprehension . Unfortunately, using these scale takes time, and for patients with cognitive impairments, i.e. almost half of the patients in falls consultations, it is quite problematic to administer these scales (scoring difficulties especially with visual scales) .

In spite of the validated efficacy of the therapeutic care proposed in the multidisciplinary falls consultation , one of the limits of this study is the lack of comparative data 6 months after the first evaluation on the prevalence of the fear of falling, the capacity of patients to go out of their homes and the frequency of their outings. Finally, a 6-month delay for follow-up is interesting for appreciating the recurrence or not of falls, but it is probably too short to observe an association between the fear of falling and placement in a medical living environment.

1.5

Conclusion

The fear of falling is quite common in elderly fallers. Women, persons with a history of recurrent falls, persons who spent a long time on the floor after a fall, persons with balance disorders are more prone to have fear of falling. This apprehension of falling is often translated, in these patients, into a restriction of activities, as we observed with a significant reduction in the activity “going out of the home alone”. We encourage seeking the fear of falling in elderly patients who are fallers or at risk of falling in order to better adapt their therapeutic care.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La chute compte parmi les dix premières causes de décès du sujet âgé et représente après 70 ans, la première cause de décès de cause accidentelle. Un tiers des personnes âgées à domicile et la moitié des personnes âgées institutionnalisées chutent chaque année. La peur de tomber est fréquente chez le sujet âgé, qu’il soit chuteur ou non , s’accompagnant volontiers d’une restriction d’activité . Elle est un facteur de risque de chuter, particulièrement lorsqu’elle s’intègre dans le syndrome post chute ou syndrome de désadaptation psychomotrice (SDPM) .

Les termes sensation d’insécurité, d’appréhension, d’anxiété, d’évitement de certaines activités… sont d’autres termes utilisés pour définir la peur de tomber . Il existe autant d’échelles de mesure de la peur de chuter que de définitions de celle-ci (plus de 20) . La variabilité de ces échelles et de la définition de la peur de chuter qu’elle sous-entend entraîne une grande disparité des chiffres de prévalence de ce phénomène . La restriction des activités chez le chuteur est parfaitement décrite . Elle peut être protectrice à court terme en limitant le risque de nouvelle chute, mais se révèle délétère à long terme, car responsable d’une diminution des capacités physiques. La restriction d’activité liée à la peur de tomber est corrélée à la notion de chute traumatisante dans l’année écoulée, à l’existence de comorbidités, à la présence de symptômes dépressifs et à la diminution des performances physiques . La peur de tomber explique la restriction de certaines activités des sujets âgés comme se baisser, atteindre quelque chose au-dessus de sa tête, une diminution de la fréquence des sorties hors du domicile, en particulier, des sorties associées à des activités sociales (office religieux, club, visite à des amis ou à la famille…) .

Notre travail avait, pour objectif principal, de déterminer la prévalence de la peur de tomber des patients rencontrés en consultation multidisciplinaire de la chute au centre hospitalier régional universitaire (CHRU) de Lille, appréciée par une échelle d’évaluation dichotomique « Avez-vous peur de chuter ? Oui/Non » ; les objectifs secondaires étaient de déterminer les facteurs associés à la peur de tomber ; et de préciser le retentissement de la peur de tomber sur l’activité « sortir de chez soi ».

2.2

Patients et méthodes

La consultation pluridisciplinaire de la chute du CHRU de Lille a été créée, en 1995, au sein de l’hôpital gériatrique Les-Bateliers. Tous les patients rencontrés à la consultation multidisciplinaire de la chute du CHRU de Lille de 1995 à 2006 ont été inclus. Chaque patient est successivement examiné par un gériatre, un neurologue et un médecin rééducateur .

L’examen initial est analytique, fonctionnel et environnemental. Les variables recueillies à l’aide d’un dossier standardisé comprennent les données sociodémographiques (âge, sexe, mode et lieu de vie, niveau d’études, profession), les antécédents médicaux, le traitement habituel. Le poids et la taille sont mesurés permettant de calculer l’index de masse corporelle (IMC). L’autonomie est évaluée par l’Activity of Daily Living (ADL) . Les fonctions cognitives sont évaluées par le Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) . Nous avons considéré comme déments les patients avec un MMSE inférieur ou égal à 24, les patients avec un diagnostic connu de démence avant la consultation, ainsi que les patients pour lesquels un diagnostic de démence a été porté dans les six mois suivant la consultation (indépendamment du score MMSE). Les circonstances des chutes, leur nombre au cours des six mois précédant la consultation et le temps maximal passé au sol après la chute sont précisés. L’interrogatoire du patient et de l’aidant identifie aussi les facteurs comportementaux et environnementaux. L’examen physique précise les facteurs individuels favorisant ou précipitant les chutes et recherche de manière systématique les troubles de la marche et de l’équilibre. Un trouble de l’équilibre était défini par un déséquilibre en station bipodale les yeux ouverts ou les yeux fermés ou par l’absence d’adaptation posturale à la poussée sternale. Les données de l’examen clinique et la description de la marche rapportée en toutes lettres par chaque praticien ayant examiné le patient nous ont permis de classer les troubles de la marche de manière rétrospective pour chaque patient selon la classification proposée par Alexander et Goldberg, en 2005 . Les patients pour lesquels nous n’avons pu établir avec précision de trouble de la marche ont été classés dans le groupe « marche non étiquetée » de cette classification et non considérés pour l’analyse statistique. La forte prévalence des pathologies neurologiques rencontrées chez les consultants justifient pleinement la présence du neurologue .

Quatre questions évaluent la peur de tomber ( Tableau 1 ).