Abstract

Introduction

In cases of agitation and aggressive behavior after severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), the benefits/risks ratio of pharmacological treatments remains unclear. A qualitative analysis of clinical situations could highlight the relevance of psychotherapy care.

Case report

In January 2005, this 24-year-old patient sustained severe traumatic brain injury (Glasgow at 4/15), with bilateral frontotemporal injury and temporal extradural hematoma. On the third day, a temporal lobectomy was performed. The patient’s evolution showed severe neurobehavioral disorders, with agitation and aggressive behavior towards family members and medical caregivers. Maximum doses of antipsychotic drugs brought no improvement. Antidepressant medication improved social contact. Several stays in the psychiatric unit, where institutionalized and psychotherapy care were implemented, showed systematically a real improvement of the behavioral disorders, increased participation in group activities and the ability to walk around alone in a closed environment.

Discussion/conclusion

Aggressive behavior can unveil organic brain injuries, depressive syndrome as well as iatrogenic nature of the environment. This clinical case is based on the fact that antipsychotic drugs, aside from their sedative effect, are not the proper treatment for agitation following traumatic brain injury. This case also highlights how management of behavioral disorders following TBI should not be based on pharmacological treatments only but instead should focus on multidisciplinary strategies of care.

Résumé

Introduction

Dans les cas d’agitation et d’agressivité secondaire à un traumatisme crânien (TC) grave, le rapport bénéfice/risques des traitements médicamenteux est discuté. L’analyse qualitative de situations cliniques peut permettre de dégager l’efficacité de prises en charge psychothérapeutiques.

Observation

Un patient de 24 ans présente en janvier 2005 un TC grave (Glasgow 4/15) avec des lésions intraparenchymateuses frontotemporales bilatérales et un hématome extradural temporal gauche. À j3 une lobectomie temporale droite est réalisée. L’évolution est marquée par des troubles du comportement majeurs avec des gestes hétéroagressifs envers les soignants et la famille. Les troubles deviennent tels qu’il doit être maintenu dans sa chambre en dehors des activités de rééducation et des visites. Les neuroleptiques à posologie maximale sont inefficaces. Un antidépresseur permet une amélioration du contact. Plusieurs hospitalisations en psychiatrie, où une prise en charge institutionnelle et psychothérapique est mise en place, montrent systématiquement une amélioration nette des troubles du comportement, une possibilité de participation à des activités de groupe et de déambulation libre dans un espace fermé.

Discussion/Conclusion

L’agressivité peut traduire les lésions cérébrales organiques, un syndrome dépressif, ainsi que le caractère iatrogène de l’environnement. Ce cas clinique appuie le fait que les neuroleptiques, en dehors de leur effet de sédation, ne sont pas un traitement efficace de l’agitation après TC. Il permet de mettre en évidence combien la prise en charge des troubles du comportement relève surtout de stratégies autres que médicamenteuses et est à la frontière avec d’autres spécialités.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) requires multidisciplinary care on both medical and social levels. The incidence of TBI is hard to assess. In United States it is estimated at 500/100,000 inhabitants, with no distinction in severity . Jahouvey et al. reported the annual incidence of severe TBI due to traffic accidents at 13.7/100,000 inhabitants .

Severe TBI is responsible for chronic cognitive and behavioral disorders . The latter can cause difficulties for a proper social integration and can sometimes be associated to mood disorders . Behavioral disorders such as aggressiveness can be at the forefront of the clinical picture. Eleven to 34% of patients after TBI present with agitation or aggressive behavior . These disorders can linger over time and become chronic .

There are some medication strategies available, yet the benefits/risks ratio is hard to assess due to the rare number of studies with a high level of scientific evidence found in the literature . A pharmacological treatment is not the only alternative: Fayol in his review of the literature listed the various prevention and non-pharmacological strategies. He differentiated the various approaches: behavioral, global and psychotherapeutic (including systemic) often intertwined in clinical practice. The relevance of a psychological and cognitive approach has been highlighted . However, very few data exist on the efficacy of these approaches due to the difficulty in conducting high quality studies.

The great diversity of existing psychotherapeutic models and techniques enable psychiatrists to bring a pathopsychological clinical response , even if the psychiatric nosography can find limits in the description and classifications of disorders secondary to TBI . As reported by H. Oppenheim-Gluckman , psychiatry had progressively turned away from the management of patients after TBI to propose alternatively for the past twenty years new approaches at the frontiers of neurology, neuropsychology, physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) and psychiatry. At the crossroads of all these specialties we can find the issue of “behavioral disorders” . In fact this “dual” vision separating the “soma” from the “psyche” would not work in case of behavioral changes after trauma (both in the physical and psychological sense) such as TBI affecting the patient and his/her loved ones.

Taken into account the great methodological difficulty, in this field, to conduct studies on homogeneous cohorts and according to the relevance of a qualitative study extended over several years, we report here the clinical case of a patient with TBI who had access to a combination of PM&R and psychiatry care with positive results.

1.2

Clinical case presentation

Mr. X, 24-year-old, the youngest of three children, his sisters were at the time of the initial injury 26- and 30-year-old respectively. He had no previous relevant history, did not take any medical treatment. He had been living with his girlfriend for the past four years and worked as an assembly line worker. On January 22 nd , 2005 he was involved in a traffic accident responsible for severe TBI; he was driving. The initial Glasgow score was 4/15, the CT-scan showed bilateral frontotemporal brain injuries and extradural temporal hematoma on the left side. The patient had emergency surgery. Postoperative follow-up showed severe intracranial hypertension (IH), up to 50 mmHg, in spite of medical treatment at maximum dosage. Brain MRI showed enhanced mass effect with severe diffuse bilateral lesions and large hemorrhaging hematoma on the right temporal lobe. At day 3, due to the uncontrollable intracranial pressure, a lobectomy of the right temporal lobe was performed by the surgical team. Following surgery IH gave way and the arousal phase started. The tracheotomy was taken out on April 5 th 2005 and the patient was transferred to the PM&R centre on April 7 th 2005.

Upon admission the patient had very few spontaneous movements; there were no obvious motor impairments. Oral expression was reduced to screams and grunts. The patient did not seem to recognize his loved ones. The patient was fed through a gastrostomy tube.

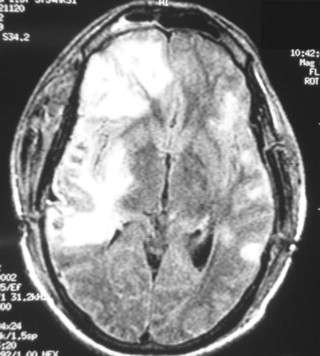

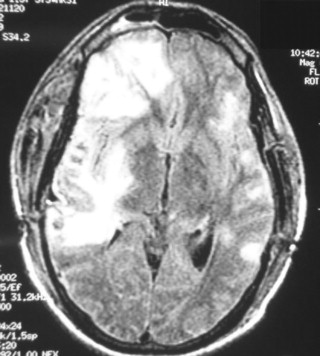

The evolution validated the lack of motor impairments but alongside the improvement of motor capacities the cognitive and behavioral disorders became more obvious. Brain MRI done on April 22 nd 2005 showed dilatations of the ventricles with right-sided frontotemporal gliosis ( Fig. 1 ). Based on the hypothesis of hydrocephalus being the potential and curable cause of this slow arousal we started mid-June 2005 with repeated spinal taps to drain excessive CSF to no avail. There was no evidence of pain, spontaneous or provoked. The gastrostomy tube was taken out in November 2005 returning to normal feeding without swallowing disorders. Standing and walking were initiated during the month of August 2005. However, right from the beginning of the arousal process the following symptoms appeared: disorganized psychomotor agitation, screams and aggressive gestures towards the medical staff, at first during invasive procedures such as injections but also during nursing care.

At the end of 2005, 12 months after the initial injury, the patient did not seem to have recovered from posttraumatic amnesia. There were no motor impairments. The contact with the patient was quite difficult to establish and needed to be very progressive. The patient’s oral communication consisted in incomprehensible words, swears words, or continuous screaming, sometimes some paraphasias. Oral comprehension could not be formally tested. Simple orders did seem to be understood by the patient. The use of daily life objects (fork, comb) was inadequate and there seemed to be praxis disorders as well. On a behavioral level, there was a non-directed agitation but also some “directed” aggressive gesture (towards any type of nursing care, or due to frustration). There was associated bulimia, non-selective polyphagia, hyperorality, inappropriate urination/defecation behaviors and sexual conduct disorders (e.g. masturbating in public). The patient also developed stereotyped motor disorders, prolonged crouch-down position on the bed, rocking back and forth either when sitting down or when standing in front of a window. Regarding the patient’s mood, there was a probable sadness with underlying anxiety as seen in the uninterrupted screams (crying?) and when hitting caregivers.

Progressively, his aggressive behavior got worse. Not only towards the medical staff but also with family members in spite of efforts from the entire medical team and help from the family associated to increased dosage of antipsychotic drugs. Rehabilitation training sessions were conducted under constant monitoring from the physiotherapist (if not there were risks of aggressive or violent gestures towards other patients), nursing care required at least four staff members, any physical contact could prompt the patient to hit members of the medical staff. This situation was so critical that it was impossible to let the patient walk around by himself outside his room (so the door had to be locked from the outside) because he could harm other patients. His aggressive behavior consisted in several violent gestures per day such as biting, scratching or screaming and it had heavy consequences on staff members (repeated work injuries, complaints of the staff reported to the management). The patient was unable to name his closed ones. Nevertheless, his behavior with them was quite different according to his closed ones. The aggressive behavior was identical towards both parents, and there were repeated episodes of physical attacks on his mother. Only his girlfriend seemed to be able to establish close enough relations without triggering an aggressive reactional behavior from the patient. The patient’s family was very present and supportive throughout the patient’s hospitalization time, they came several afternoons per week and were very friendly with the staff. The family’s moral distress and concern was considerable and kept increasing during the patient’s hospital stay.

The psychotropic treatment had greatly increased, associating several high doses of neuroleptic drugs, mood stabilizers, antidepressants and several benzodiazepines.

The daily doses used were:

- •

for the antipsychotic drugs: loxapine 400 mg, cyamemazine 375 mg, methotrimeprazine 250 mg, olanzapine 20 mg, risperidone 4 mg;

- •

for antiepileptic drugs: oxcarbazepine 1200 mg;

- •

for benzodiazepines: clorazepam 120 mg, diazepam 80 mg, prazepam 60 mg;

- •

anticholinergics and antidepressants were also used: hydroxyzine 300 mg, paroxetine 40 mg, mirtazapine 30 mg, citalopram 40 mg.

However the proper balance was impossible to find between severe sedation (implying loss of contact and risk of aspiration pneumonia) and a too-limited action on the patient’s aggressive behavior. An antidepressant drug prescribed in January 2006 (paroxetine) did decrease the screaming. The antidepressant treatment was continued up to 2009 while trying different molecules (paroxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine).

Thus, in spite of multidisciplinary care and various antipsychotic treatments the patient’s aggressive behavior was so severe that he had to be hospitalized in the psychiatric unit in December 2005. The objectives were to conduct a special evaluation of the patient’s mood and behavior, propose a therapeutic adjustment and relay the treatment with another medical team. The disorders were so severe that a standardized behavioral evaluation was not possible, but the clinical analysis of the patient’s evolution was highly significant.

The first hospital stay lasted three weeks in the psychiatric unit in December 2005. The therapeutic care associated to a different organization of care: i.e. possibility for the patient to walk more freely, lesser solicitation from the nursing staff and changes in the neuroleptic medications to maintain proper contact. Two antipsychotic drugs (cyamemazine, olanzapine) and an antiepileptic drug (oxcarbazepine) were stopped in favor of another antipsychotic drug (pipamperone). After the three-week period, the aggressive behavior improved to the detriment of verbal contact. However, as soon as the patient was back in the PM&R unit and in spite of maintaining the medical treatments implemented in the psychiatric unit, the aggressive behavior clearly got worse. Family members who were initially against this psychiatric hospitalization did notice its positive therapeutic effect on the patient’s behavior. They were in favor of a new hospital stay in the psychiatric unit.

In February 2006 a second psychiatrist stay was planned for a month, it offered therapeutic care focused on ritualized nursing care, by two staff members, adopting a soothing attitude and progressive contact with the patient (first visual, then verbal and finally physical, allowing the patient to participate). The pharmacological treatment was again updated (introduction of propericiazine associated to hydroxyzine).

From 2006 to 2008, the patient was hospitalized seven times in the same psychiatric unit, each time for one-month stay. The pharmacological treatment was often changed during these psychiatric stays (trials of various antipsychotic and anxiolytic drugs), without evidence of continuous efficacy on the long-term. Then the medical teams and family members realized that it was the hospitalization in the psychiatric unit itself that was useful, regardless of the pharmacological treatment. Any behavioral improvement in psychiatry was followed by an aggravation of the disorder upon returning to the PM&R unit even though the pharmacological treatment remained unchanged.

In 2007, Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy sessions were started (with two healthcare staff members for two patients), in partnership with the long term unit of the specialized psychiatric hospital. The relaxation therapy sessions in the PM&R environment had always failed. In June 2008 the patient was fully admitted to this unit. His loved ones were quickly convinced of the efficacy of psychiatric institutionalization, and even more so in the specialized long-term unit, since the patient behavior had improved so much.

By May 2009, the patient’s independence had increased greatly, he was now able to wash and get dressed by himself upon stimulation. On a behavioral level, the spontaneous aggressive gestures towards others had become very rare; the intolerance to frustration remained. The patient was able to walk freely around the FAM unit, a closed-off unit with a courtyard, just like any other resident. He participated in group activities (e.g. meals, drawing, physical activities). Physical contact was now possible without being felt as intrusive by the patient, that contact happened mainly during the Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy sessions or aquatic therapy. There were some phasic disorders for comprehension with sometimes proper verbal production, screaming episodes had become very rare. There were some major memory disorders but he was able to recognize some members of the medical staff. There was no clear ideomotor apraxia, but some disorders of the executive functions with lack of initiative. Hyperorality and bulimia had decreased just like the inappropriate sexual conducts. In fact, there were some acquisitions, probably implicit ones, but language disorders prevented from conducting regular evaluations and there was no possibility to determine if there was some memory fixation.

1.3

Discussion

We report the clinical case of a patient with severe TBI and major aggressive behavior not improved by PM&R care. This behavior had psychological consequences both on the patient’s family and medical staff. Individualized PM&R care associated to a pharmacological treatment did not significantly decrease the symptoms. The clinical situation brought the PM&R team and the family to agree to psychiatric institutionalization rather than inefficient back and forth stays between the PM&R and psychiatric units. This institutionalization brought significant improvements on the patient’s aggressive behavior, attributed more to changes in the patient’s environment than changes to the pharmacological treatment.

First we will look at the semiological analysis of this clinical case, before discussing pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapeutic care.

1.3.1

Semiological analysis

Major aggressive behavior towards others is at the forefront of the patient’s symptoms. This symptom is not rare after TBI . A literature review of the guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury , reported that 11 to 34% of patients after TBI present some agitation or aggressive behavior according to the Overt Aggression Scale . This aggressive attitude can be associated to a depressive syndrome .

In this clinical case the symptoms are atypical, not only with the severe aggressive behavior but also hyperorality and stereotyped motor movements presented by the patient. “Behavioral disorders” post severe TBI can be correlated to brain injuries. Severe TBI is the cause of focal lesions associated to diffuse lesions, with a possible alteration of the cognitive functions. This explains, in this clinical case, the severe cognitive and behavioral impairments. For this case we can bring up the Kluver-Bucy syndrome . Described initially in primates, it is sometimes incomplete in humans. The association of major memory disorders and indiscriminate hyperorality, bulimia, hyperphagia, sexual conduct disorders points towards this syndrome seen after bitemporal lesion. One of the symptoms of this syndrome is generally a placid behavior, yet some explosive, violent behaviors have sometimes been reported . Anatomically, bitemporal brain injury is the most common type of TBI for this syndrome, but some unilateral lesion and subdural hematoma were also reported. In this case, the temporal lobectomy is unilateral but associated to other brain lesions and temporal extradural hematoma.

Furthermore in this observation it is quite possible for the aggressive symptoms to be related to an atypical depressive syndrome. Screams, anticipating anxiety during nursing care and aggressive gestures towards others could be the symptoms. This hypothesis is even more relevant since antidepressants had positive effects on the patient’s behavior. The frequency of depressive syndromes in the eight years following TBI is quite high, from 25 to 60% . According to the review of literature by Van Reekum et al. , the relative risk of developing a depressive syndrome after TBI is 7.5.

1.3.2

On a pharmacological level

Very few studies with good level of scientific evidence are available regarding pharmacological treatment for posttraumatic behavioral disorders . The review of the literature from the Cochrane Database could not bring recommendations but it is possible that the recent mood stabilizers, antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs available on the market might be useful.

There is no validated efficacy for neuroleptic drugs after TBI. There are very effective in psychotic patients acting on productive elements, delirium and hallucinations. However, there is no notion of delirium element in this observation. In this clinical case, the medication changes implemented in the psychiatric unit never worked on the long-term outside of that unit. This clinical case highlights the fact that neuroleptics, outside of their sedative action, are not an effective treatment for agitation and aggressive behavior after TBI.

Also, the efficacy of benzodiazepines has not been validated and can have potentially adverse side effects on the posttraumatic recovery process .

In this clinical case the prescription of an antidepressant did improve contact with the patient. Even though it is impossible to establish recommendations , some studies did highlight that a combination of antidepressant treatment and mood-stabilizer/anti-epileptic drugs could have a positive impact on the aggressive behavior symptoms .

In fact, this clinical case and an analysis of the literature both show that the therapeutic care of aggressive symptoms goes beyond a simple pharmacological therapeutic care. On the one hand the therapeutic approach cannot and must not be reduced to simply prescribing medications for which there are no validated efficacy and potential adverse side effects. On the other hand it is essential to evaluate the significance of this aggressive behavior, especially identifying a potential of a depressive syndrome.

1.3.3

The non-pharmacological treatment: individual therapeutic care (multisensory stimulation therapy and psychotherapy)

In this clinical case, multisensory stimulation therapy (Snoezelen) showed some relevance. However, the studies on this technique have a low-level of scientific evidence .

The literature review from the Cochrane Database does not report an improvement on the mood, behavior or interaction in patients with dementia. However, other authors do highlight its effectiveness on the aggressive behavior of patients with dementia. Regarding autistic and mentally retarded patients, the results are either contradictory , or positive, but never significant .

To our knowledge, only one study was published on patients with TBI but it focused on children . It highlights the relevance of this technique. However it seems quite difficult to construct studies with a good level of scientific evidence for this technique. Nevertheless for patients who cannot access language-mediated psychotherapy and when medications are insufficient or even harmful, it can find its place for severe aggressive symptoms. It would seem quite appropriate to conduct further studies on the relevance of this type of therapy for patients with TBI.

The literature is poor regarding the psychotherapeutic care of posttraumatic aggressive symptoms. According to some authors, a behavioral-type attitude from the medical staff could bring some improvement on the symptoms . Global and psychotherapeutic approaches can also be interesting but rather for patients with less severe disorders .

Regarding patients with dementia, Opie in his review of the literature reports that psychosocial approaches can be effective on behavioral disorders . Another literature review promoted the efficacy of sensory-type therapeutics compared to other approaches. Furthermore, Cohen-Mansfield showed some improvements with specific and individual psychobehavioral approaches in patients with dementia and agitation.

1.3.4

Non-pharmacological treatment: institutionalized psychiatric care

In this clinical case, the obvious improvements brought by psychiatric institutionalization were not due to the changes in medications (that remained unchanged in the PM&R unit), the Snoezelen multisensory stimulation therapy (started in 2007), or any type of individual psychotherapy inaccessible to the patient. It was the hospitalization in the psychiatric unit itself that was effective.

The relevance of this clinical case is based on the other type of treatment represented by institutionalized psychiatric care. By combining lower patient’s solicitation, more opportunities to walk freely, ritualized nursing care, the psychiatric hospitalization triggers less psychological suffering for the patient who in return has less aggressive gestures towards others. Thus, institutionalized care based on an implicit learning process, with little language and no explicit memory processes seems to be an interesting alternative in this framework.

Furthermore, for this type of care it also seems that accepting the chronic nature of the symptoms was associated to not advocating “progress” or “recovery”. Faced with behavioral disorders where PM&R care could be insufficient, other types of approaches seem better suited to such particular clinical situations. Social healthcare structures, psychiatric units appear to be more in favor of adapting the environment to the person rather than changing the person’s behavior according to a set structure. According to the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), the institutionalized environment seems here to be a facilitating factor for reducing the disability.

Psychiatric care did reduce the various constraints that were triggering suffering in this patient. Furthermore, this clinical case showed that evolution of behavior, capacities and impairments after brain injury is a slow process. It underlines also that the notion of time is not to be neglected in the case of posttraumatic behavioral disorders, not only for the patient’s capacities to progress but also for the medical team to be able to adjust.

We bring forth the hypothesis that for cognitive impairment cases, PM&R teams can have difficulties in giving up the objectives of therapeutic care based on the evolution of impairments in order to envision real changes in the environment. It seems that other healthcare professionals in other institutions are more knowledgeable in this field, whether in psychiatry, social healthcare institution or geriatrics (e.g. for patients with dementia in small-family like structures “cantous”). By following inadequate objectives, putting the patient in a situation of failure, insufficient expertise from medical teams, lack of structure adaptations it can lead, just like in the clinical case, to a real iatrogenicity, partly mediated by depressive elements.

Finally, this therapeutic care can only be effective if the psychiatric team is trained and sensitive to traumatic brain injury. Multidisciplinary care can be beneficial as long as there is a dialog between PM&R and psychiatric teams, going beyond the issue of “organic” or “non-organic” etiology for behavioral disorders.

1.4

Conclusion

Regardless of TBI severity, the impact of psychiatry in the therapeutic care of behavioral disorders is important, both in the semiological analysis and in the therapeutic. This clinical case seems a perfect example of the relevance of multidisciplinary care in PM&R. Professional ties between PM&R and psychiatry appear obvious in this situation of major behavioral disorders after severe TBI. They facilitated a positive issue to a very complex situation.

The relevance of this clinical case resides also in updating another type of “treatment” for post-traumatic behavioral disorders. In fact, pharmacological treatments have once more shown their lack of efficacy (expect antidepressants). Individual care brought some improvement, but it was mainly a change in the environment and institutionalized care that resolved this therapeutic dilemma. Here the social model of disability becomes highly relevant, including when it does not lead to promoting integration in the ordinary environment, but rather adapting that environment.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Le traumatisme crânien (TC) est emblématique d’une prise en charge pluridisciplinaire, au carrefour des structures sanitaires et médicosociales. L’incidence dans la population est difficile à évaluer. Aux États-Unis, elle est évaluée à 500/100 000 habitants, tous niveaux de gravité confondus . Jahouvey et al. estiment l’incidence annuelle des TC graves par accidents de la route à 13,7/100 000 habitants .

Le TC grave est responsable de troubles cognitifs et comportementaux, qui persistent au long terme . Ces derniers peuvent être responsables de difficultés d’intégration sociale, qui peuvent être majorées par des troubles thymiques . Les troubles du comportement à type de comportement agressif peuvent être au premier plan. Onze à 34 % des patients après TC présentent une agitation ou un comportement agressif . Ces troubles peuvent persister à long terme .

Des stratégies médicamenteuses existent, dont le rapport bénéfice-risques est difficile à préciser en raison du faible nombre d’études de bon niveau de preuve . Le traitement chimiothérapeutique n’est pas la seule alternative : Fayol dans sa revue de littérature répertorie les différents axes de prévention et de traitement non pharmacologiques. Il distingue les approches comportementales, les approches globales et les approches psychothérapeutiques (dont l’approche systémique) qui dans la pratique se recoupent souvent. L’intérêt d’une approche tant psychologique que cognitive est soulignée . Cependant, peu de données existent sur leur efficacité, du fait de la difficulté à conduire des études de qualité.

La diversité des modèles et des techniques psychothérapeutiques existantes permet aux psychiatres d’apporter un éclairage clinique psychopathologique , même si la nosographie psychiatrique peut trouver des limites dans la description et la classification des troubles secondaires à un TC . Comme le rapporte H. Oppenheim-Gluckman , la psychiatrie s’était progressivement détournée de la prise en charge des patients après TC, pour proposer, au contraire, depuis une vingtaine d’années, de nouvelles approches aux confins de la neurologie, de la neuropsychologie, de la médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR) et de la psychiatrie. Au confluent de l’ensemble de ces disciplines se situe probablement la problématique du « trouble du comportement » . En effet, une vision « dualiste » séparant le « soma » de la « psyche » ne saurait être efficiente dans le cas de modifications comportementales après le traumatisme (au sens physique et psychologique), qu’est pour un patient et ses proches, le traumatisme crânien.

Compte tenu de la très grande difficulté méthodologique à rapporter, dans ce domaine, des cohortes homogènes et compte tenu de l’intérêt que peut avoir une analyse qualitative prolongée sur plusieurs années, nous rapportons ici le cas clinique d’un patient, victime d’un traumatisme crânien, pour qui une prise en charge conjointe MPR-psychiatrie a été l’alternative efficace retenue.

2.2

Présentation du cas clinique

Monsieur X, âgé de 24 ans, est le troisième d’une fratrie de trois enfants, ses sœurs sont âgées de 26 et 30 ans. Il n’a aucun antécédent et ne prend pas de traitement. Il vit en couple depuis four ans, est employé comme monteur-assembleur. Le 22 janvier 2005, il est victime d’un accident de la voie publique, au volant de sa voiture, responsable d’un traumatisme crânien grave. Le score de Glasgow initial est de 4/15, le scanner cérébral révèle des lésions intraparenchymateuses bilatérales frontotemporales et un hématome extradural temporal gauche, évacué en urgence. Les suites opératoires sont marquées par une hypertension intracrânienne sévère, jusqu’à 50 mmHg, malgré un traitement médical maximal. À l’IRM cérébrale existent une majoration de l’effet de masse, avec des lésions bilatérales diffuses importantes et une volumineuse contusion hémorragique lobaire temporale droite. À j3, en raison de l’absence de contrôle de la pression intracrânienne, une lobectomie temporale droite est décidée. L’hypertension intracrânienne cède ensuite, puis la phase d’éveil débute. La trachéotomie est ôtée le 5 avril 2005 et le patient est transféré au centre de MPR le 7 avril.

À l’arrivée, il existe peu de mouvements spontanés, il n’y a pas de déficit moteur évident. L’expression orale est réduite à des cris et des grognements. Le patient ne paraît pas reconnaître ses proches. L’alimentation se fait par l’intermédiaire d’une sonde de gastrostomie.

L’évolution confirme l’absence de déficit moteur, mais parallèlement à l’amélioration des possibilités motrices, les troubles cognitifs et comportementaux apparaissent plus prégnants. L’IRM cérébrale du 22 avril 2005 met en évidence une dilatation ventriculaire avec zone de gliose parenchymateuse frontotemporale droite ( Fig. 1 ). Dans l’hypothèse d’une hydrocéphalie comme cause curable d’un éveil lent, on procède mi-juin 2005 à des ponctions lombaires évacuatrices qui sont sans effet. Il n’y a pas de douleur évidente, spontanée ni provoquée. La gastrostomie est ôtée en novembre 2005 avec reprise d’une alimentation normale sans trouble de déglutition. La station debout et la marche sont reprises courant août 2005. Cependant, dès le début de la phase d’éveil apparaissent une agitation psychomotrice désordonnée, des cris, et des gestes hétéro-agressifs envers les soignants, initialement lors des soins potentiellement « intrusifs » comme les injections sous-cutanées, mais également lors des soins de nursing.