Fasciotomies of the Lower Extremity

Christopher J. Salgado

Amir A. Jamali

Jason Nascone

Indications/Contraindications

Compartment syndrome is the most common indication for fasciotomy. Compartment syndrome is a clinical condition with elevated tissue pressure within a closed anatomic compartment. Muscles are contained within an osseofascial compartment that has a limited capacity to expand. The causes of compartment syndrome can be divided into two major categories: decreased compartment size and increased compartment volume. Decreases in compartment size can be due to extrinsic factors such as tight dressings or casts or due to intrinsic causes such as bleeding into a compartment after injury or a postoperative coagulopathy. Increased compartment volume can occur at the macroscopic or microscopic level. Bleeding or iatrogenic infiltration of intravenous fluid into a closed compartment are both common causes of compartment syndrome. At the microscopic level, compartment volume can be increased in proportion to either increased capillary permeability and/or capillary pressure. Conditions associated with tissue damage such as burns, ischemia/reperfusion, and trauma can all lead to increased capillary permeability. Increased capillary pressure is the underlying cause of compartment syndrome due to venous obstruction or exercise.

The underlying pathologic condition leading to compartment syndrome is an elevated tissue pressure which leads to decreased arteriolar perfusion. At this point shunting occurs, bypassing the capillary circulation which then worsens the tissue ischemia, and in turn, increases the capillary permeability and interstitial tissue pressure. This vicious cycle can quickly lead to permanent tissue damage if not treated expediently. The tissues most at risk in compartment syndrome are the nerves and muscles. If untreated, compartment syndrome can lead to Volkmann’s contracture, a permanent paralysis of muscles in the compartment with scarring in a shortened position leading to the term “contracture.” Assessment of an injured lower extremity must include a thorough evaluation of factors, which can contribute either directly or indirectly to compartment syndrome. A list of such factors is given in Table 30-1. The treatment of compartment syndrome is the correction of the underlying pathologic state and the performance of a fasciotomy. Fasciotomy is the incision of fascial compartments in order to expand the size of the compartment and to restore tissue perfusion to the contents of the compartment.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning of a fasciotomy is based on an accurate and timely diagnosis of compartment syndrome. The most important data guiding this decision is the clinical examination. In the setting of an awake, unsedated patient, the diagnosis can commonly be made based on clinical grounds. The classical clinical signs of compartment syndrome are the six P’s: pain, pressure, paresthesia, paralysis, pallor, and pulselessness. Note that significant muscle damage occurs prior to the onset of pallor, pulselessness, and paralysis, and that these are late findings of a missed compartment syndrome. The most sensitive clinical sign of compartment syndrome is pain. This is often described as being out of proportion to the injury. In the author’s experience, the variability of pain threshold among

patients can make the assessment of “expected level of pain” somewhat arbitrary. The presence of a greater than expected level of pain does not indicate definitive compartment syndrome and the absence of pain does not rule out the diagnosis, particularly in the setting of a possible neurologic injury. The use of sedatives and analgesics, a history of central nervous system trauma, and the possibility of peripheral nerve injury highlight the need for a high index of suspicion and the need for early intracompartmental pressure measurements. Passive stretching of muscles within the compartment leads to elevated pressures and increased pain, another valuable tool in establishing a clinical diagnosis. Other signs of compartment syndrome include paresthesias and paralysis. Paresthesias are due to ischemic damage to the peripheral nerves running in the compartment. Decreased 2-point discrimination is the most consistent early finding. Correlation has also been reported between diminished vibration sense (256 cycles per sec) and increasing compartment pressure. On deep palpation, a firm wooden feeling is a specific sign when present. Bullae may also be observed. In later stages, the paresthesias can progress to complete anesthesia in the distribution of the peripheral nerve.

patients can make the assessment of “expected level of pain” somewhat arbitrary. The presence of a greater than expected level of pain does not indicate definitive compartment syndrome and the absence of pain does not rule out the diagnosis, particularly in the setting of a possible neurologic injury. The use of sedatives and analgesics, a history of central nervous system trauma, and the possibility of peripheral nerve injury highlight the need for a high index of suspicion and the need for early intracompartmental pressure measurements. Passive stretching of muscles within the compartment leads to elevated pressures and increased pain, another valuable tool in establishing a clinical diagnosis. Other signs of compartment syndrome include paresthesias and paralysis. Paresthesias are due to ischemic damage to the peripheral nerves running in the compartment. Decreased 2-point discrimination is the most consistent early finding. Correlation has also been reported between diminished vibration sense (256 cycles per sec) and increasing compartment pressure. On deep palpation, a firm wooden feeling is a specific sign when present. Bullae may also be observed. In later stages, the paresthesias can progress to complete anesthesia in the distribution of the peripheral nerve.

Table 30-1. Compartment Syndrome Risk Factors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paralysis can be due to muscle ischemia, nerve ischemia, direct injury to these structures, or secondary to pain inhibition. Pulselessness is uncommon in an isolated compartment syndrome and heralds a probable vascular injury. Laboratory testing revealing a creatine kinase (CK) of 1,000 to 5,000 U/mL or higher or the presence of myoglobinuria may alert the physician to the occurrence of compartment syndrome. When the clinical picture is borderline, compartment pressure measurements must be performed as soon as possible.

A number of techniques have been employed to determine compartment pressures, including variations in size and needle design. At our institution all compartment measurements are performed with a side-port needle attached to a commercially available pressure monitor (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) or a standard arterial line pressure transduction line (Fig. 30-1). The Stryker pressure tonometer is widely used, and pressure measurements from the Stryker device are within 5 mm Hg of the slit catheter for 95% of all readings. Measurements with a standard 18-gauge needle are not accurate and are not recommended. Pressure measurements should be performed within all compartments and at multiple sites.

The compartment pressure data can be viewed in isolation or in relation to the patient’s diastolic blood pressure. Although there is no absolute minimum compartment pressure value, most current literature indicates that the ΔP value from measured compartment pressure to diastolic blood pressure is a more valuable guide in performance of a fasciotomy. Studies suggest that the ischemic threshold of muscle is a perfusion pressure of at least 20 mmHg between the compartment pressure and the diastolic pressure. The ΔP is a direct measure of the pressure gradient between diastolic blood pressure and the tissue pressure within the compartment, indicating the presence of shunting. At our institution, a ΔP of 30 mmHg combined with increased palpable pressure is a strong indication and a ΔP of 20 mmHg an absolute indication for fasciotomy.

Therapy is begun for the treatment of compartment syndrome while preparations are made for actual surgical decompression. The affected limb(s) are placed at the level of the heart. Elevation is

contraindicated because it decreases arterial inflow and narrows the arterial-venous pressure gradient and thus worsens the ischemia. If a cast is on the affected extremity, releasing one side of the plaster cast can reduce compartment pressure by 30%; bi-valving can produce an additional 35% reduction; and cutting the cast padding may further decrease compartmental pressure by 10% to 20%. In cases of snake envenomation, administration of antivenom may reverse a developing compartment syndrome. Hypoperfusion may be corrected with crystalloid and blood products, and mannitol may reduce compartment pressures and lessen reperfusion injury.

contraindicated because it decreases arterial inflow and narrows the arterial-venous pressure gradient and thus worsens the ischemia. If a cast is on the affected extremity, releasing one side of the plaster cast can reduce compartment pressure by 30%; bi-valving can produce an additional 35% reduction; and cutting the cast padding may further decrease compartmental pressure by 10% to 20%. In cases of snake envenomation, administration of antivenom may reverse a developing compartment syndrome. Hypoperfusion may be corrected with crystalloid and blood products, and mannitol may reduce compartment pressures and lessen reperfusion injury.

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) is a valuable adjunct in the treatment of compartment syndrome. It promotes hyperoxic vasoconstriction, which reduces swelling and edema and improves local blood flow and oxygenation. It also increases tissue oxygen tensions and improves the survival of marginally viable tissue. The best results are obtained when therapy is started early after fasciotomy. Twice-daily treatments at 2.0 atmospheres absolute (ata) to 2.5 ata for 90 to 120 minutes for 5 to 7 days, with frequent examinations of the affected area, may be beneficial. This may be more practical in centers familiar with the use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Vacuum-assisted closure devices (VAC) have a number of advantages in the treatment of post-fasciotomy wounds. They reduce interstitial edema and provide a one-way flow of exudate from the wound. Additionally, this therapy increases granulation tissue formation and may lead to an earlier ability to close or skin graft the wound.

Fasciotomy of the Thigh

Thigh and gluteal compartment syndromes are uncommon and may often go unrecognized. The pathophysiology and the principles of diagnosis and treatment, however, are the same as those for other compartment syndromes. Gluteal compartment syndromes are often associated with substance abuse and a prolonged period of unconsciousness or recumbency and can occur in the absence of any obvious trauma. As a result of the large muscle mass involved, systemic manifestations of a crush syndrome are usually present. Altered mental status and metabolic abnormalities may distract from the primary problem, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. The proximity of the sciatic nerve can result in compression-induced neuropathy.

Clinical Findings

Thigh compartment syndrome is rare because of the large volume required to cause a pathologic increase in the interstitial pressure. It may occur in the setting of high-energy thigh trauma such as femur fractures with an associated crush component. These patients often have pain and swelling after fixation, which may confound the diagnosis. In addition, these trauma patients are often obtunded and require substantial fluid resuscitation, increasing the risk of compartment issues. The fascial compartments in the thigh blend anatomically with muscles of the hip, potentially allowing extravasation of blood outside these compartments. Anticoagulation can be a major risk factor leading to bleeding into the thigh compartments and the development of a compartment syndrome.

Patient Positioning

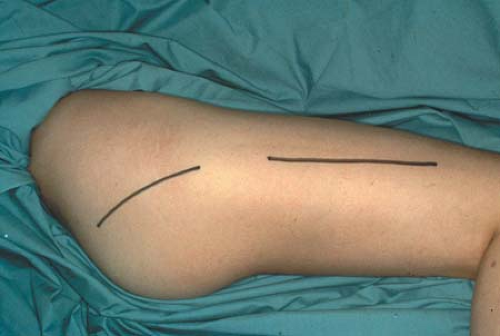

The approach to thigh compartments may be medial or lateral depending on the area of injury or suspected hematoma. The thigh should be prepared from the iliac crest to the knee joint with the patient in either the lateral decubitis position or supine.

Technique

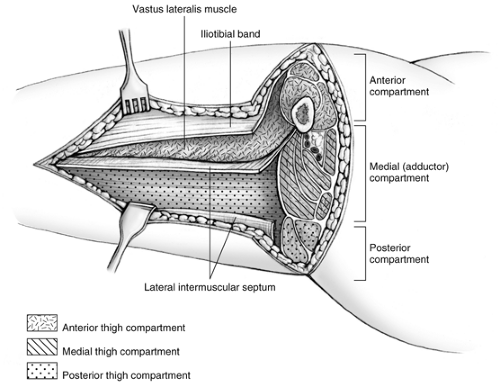

For lateral and posterior compartment syndromes, the skin and subcutaneous tissues are incised beginning just distal to the intertrochanteric line and extending to the lateral epicondyle of the femur to expose the iliotibial band or fascia lata (Fig. 30-2). The iliotibial band is incised for the length of the incision. The vastus lateralis muscle is reflected superiorly and medially to expose the lateral intermuscular septum, which is incised for the length of the incision, thus freeing the posterior compartment. Caution is required to control the perforating branches of the descending branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery traversing the lateral intermuscular septum (vessels which supply the anterolateral thigh skin), since these may retract and bleed during this portion of the decompression (Fig. 30-3). After the anterior and posterior compartments have been released, measure the pressure of the medial compartment. If elevated, then the compartment can be approached through a separate medial incision. The incision is carried along the course of the saphenous vein. Reflect the sartorius muscle superiorly, and incise the medial intermuscular septum. Intramuscular hematomas may require release through gentle muscle splitting. The wounds are packed open and a large bulky dressing applied or, alternatively, a vacuum-assisted closure device is applied.

Two to three days later, the patient is returned to the operating room for debridement of any nonviable tissue. If there is no evidence of necrotic tissue, the skin is either loosely closed, packed once again for closure at a later date, or again covered with a vacuum-assisted closure device. Often a medial thigh fasciotomy is not needed once a lateral release is performed.

Results

Because this diagnosis is not always obvious, the surgeon must maintain a high index of suspicion. Early treatment by operative compartment release follows anatomic tracts and produces good results.

Fasciotomy of the Leg

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree