Extra-Articular Lesions

Aaron A. Bare MD

Carlos A. Guanche MD

The anatomic and biomechanical considerations involved with these injuries include some of the more complex areas of the musculoskeletal system with a large overlap between the intra-abdominal contents and the pelvic musculature. The immature skeleton can add significant levels of complexity and broaden the differential diagnosis.

The body’s center of gravity is located within the pelvis, immediately anterior to the second sacral vertebra. Loads that are generated or transferred through this area are important in virtually every athletic endeavor.

The incidence of groin pain accounts for only approximately 5% of patient injuries, but is responsible for a large proportion of time loss from competition.

Athletic pubalgia may be the more appropriate term than sports hernia in many cases because an actual hernia is not seen.

The physical examination for a possible sports hernia includes a thorough assessment of the pelvic musculature and plain radiographs to assure no significant bony pathology is present.

The most common athletic injuries about the hip and groin are muscle strains. In an adolescent athlete, the same eccentric mechanism leading to a muscle strain may cause an apophyseal avulsion.

There appears to be a predisposition for the development of stress fractures in females with rates as high as four to ten times that of males. Amenorrhea appears to be especially prevalent in endurance athletes with notable decreases in bone mineral density as compared to those menstruating normally. The important principle is that a menstrual and dietary history should always be included in the diagnosis and treatment of the female athlete with potential stress fracture.

Avulsion fractures are most commonly seen in athletes between the ages of 14 and 17 years of age with males more commonly affected.

Avulsion fractures often occur during athletic competition. The mechanism of injury is a powerful muscle contraction that takes place during sprinting, while playing soccer or football, or in sports that require jumping. The clinical presentation is usually localized swelling, tenderness, and limitation of motion of the hip, secondary to pain.

Osteitis pubis is an unusual injury that occurs more commonly in long-distance runners. The mechanism of injury appears to be overtraining of the rectus abdominis and adductor muscles.

Pudendal neuropathy can cause groin pain and numbness, often exacerbated in the seated position and relieved by standing or lying supine.

Obturator nerve entrapment can cause groin pain in athletes. The cause of the nerve entrapment is uncertain. Repetitive kicking, side-to-side movements, and twisting are common motions which correlate with the problem.

Referred pain from lower lumbar and sacral nerves frequently cause gluteal or posterior thigh symptoms. Facet joint and erector spinae muscle abnormalities may also refer pain.

Groin and hip symptoms have a large overlap with many disciplines of medicine from the orthopaedic surgeon to the neurologist, the general surgeon, gynecologist, and endocrinologist. It is important to maintain this perspective and to seek appropriate consultations.

Orthopedic injuries about the hip and groin occur at a low frequency relative to injuries distal to the hip. Epidemiological studies have shown that injuries to the hip region comprise approximately 5% to 9% of the injuries in high school athletes (1). The incidence of hip pathology appears to be expanded as a result of an increased fund of knowledge in this area. This has occurred as a result of the improved imaging modalities as well as the implementation of hip arthroscopy.

The anatomic and biomechanical considerations involved with these injuries include some of the more complex areas of the musculoskeletal system with a very large overlap between the intra-abdominal contents and the pelvic musculature. This makes the management of these injuries very challenging. Also, the immature skeleton can add significant levels of complexity and broaden the differential diagnosis.

In addition to the complex anatomic considerations involved, the hip joint can see loads of up to eight times body weight, with even larger loads present during vigorous athletic competition (2). It appears that the structures about the hip are uniquely adapted to transfer such forces. The body center of gravity is located within the pelvis immediately anterior to the second sacral vertebra. This becomes increasingly important when one realizes that loads that are generated or transferred through this area are important in virtually every athletic endeavor (3).

Imaging modalities are now available that can help clinicians diagnose more accurately. They may provide indirect diagnostic and prognostic information. In addition, an important aspect of many hip and pelvic injuries is that of rehabilitation. The importance of trunk stability rehabilitation is being increasingly recognized and plays a part in many common injuries (4).

Finally, as a result of the large anatomic overlap between several disciplines, several different medical and surgical specialties may be involved in the treatment of a patient with many of these injuries.

This chapter will delineate many common hip injuries. These can be broken down into several components, namely soft tissue injuries, bony injuries, and nerve injuries. Many of the soft tissue injuries are particularly troublesome to the average sports medicine physician as the result of the large overlap with general surgical problems including those of hernias. In addition, there are several bursae around the pelvis and hip which can cause a significant amount of symptomatology and, in some cases, are misdiagnosed as a result of their unusual presentation.

Bony problems can be separated into a variety of injuries. Stress fractures can have a very insidious onset. Osteitis pubis is another poorly understood condition that can impact athletes and whose treatment is simple; however, the diagnosis is often not made until much later in the course. Neural injuries likewise are unusual in presentation. The most common injuries are meralgia paresthetica, obturator nerve entrapment, and sciatica.

Sports Hernias

While the incidence of groin pain accounts for only approximately 5% of patient injuries, it is responsible for a very large proportion of time loss from competition (5,6). The sports hernia, also known as the hockey hernia, has become a more common injury in athletes participating in sports requiring repetitive twisting and turning such as ice hockey, tennis, field hockey, soccer, and American football. The incidence in several high level athletic groups has been documented to be significantly increased over the last decade (7). Although it is true that the increased frequency of this diagnosis may be partly attributable to the heightened awareness of trainers and physicians, there is also the notion that the increasingly rigorous off season conditioning programs that concentrate on strengthening the lower extremities, but neglect the abdominal and pelvic musculature cause a significant imbalance, and may contribute to this problem. In addition, various theories regarding contractures of the hip flexor and adductor muscles are developing as a result of this preferential strengthening of one muscle group over another. One study has attempted to document radiographically a lack of hip extension when pelvic tilt is controlled (8). In this study, 25 professional hockey players and 25 age-matched controls were evaluated using the Thomas test and an electrical circuit device to determine pelvic tilt motion. The results demonstrated that the players had a reduced maximum hip extension in comparison with age-matched controls. The authors theorized that hockey players demonstrated a decreased extensibility of the iliopsoas musculature.

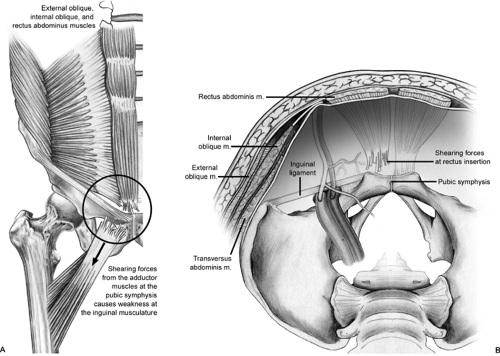

In making the diagnosis of a sports hernia, the more appropriate term may be that of athletic pubalgia since in many cases an actual hernia is not seen (9). Although the definite pathophysiology behind the development of this problem has not been implicated in overuse syndrome, in most of the athletes involved, a series of hip abduction/adduction and flexion/extension maneuvers with the resultant pelvic motion may produce a shearing force across the pubic symphysis leading to stress in the inguinal wall musculature perpendicular to the fibers of the muscle. In these cases a chronic pull from the adductor musculature against a fixed lower extremity can cause significant shear forces across the hemipelvis with subsequent attenuation or tearing of the transversalis fascia or the conjoined tendon (10). In some studies there have also been changes noted at the rectus abdominis muscle insertion (9), while in some situations, avulsions of part of the internal oblique muscle fibers at the pubic tubercle have also been documented (11). One additional theory suggests that entrapment of the genital branches of the ilioinguinal or genital femoral nerves may be the source of pain in some patients (12).

In, summary, it is apparent that the variety of abnormalities that have been reported leading to the diagnosis of sports hernias are a clear indication for the need to further delineate this area through research. In order to understand the treatment, however, it is best to think of these problems as a relative incompetence of the abdominal wall musculature in the absence of a clinically detectable hernia bulge (Fig 29-1).

Although the diagnosis of a sports hernia is made in many patients retrospectively or after eliminating the more common injuries noted about the pelvis, it is important to know the common presenting symptoms. Often, there is an insidious onset of unilateral groin pain, although some present with bilateral symptoms. Many are evaluated for a common inguinal hernia that is not typically seen and are then further misdiagnosed. In some cases, an acute tearing sensation is felt by the patient, making a diagnosis somewhat more straightforward. In many cases pain usually occurs only during exercise. It does not typically become exacerbated with coughing or sneezing as is often seen in an inguinal hernia.

Fig 29-1. Diagrammatic representation of the typical pathology encountered in a sports hernia as compared to the more common inguinal hernias. A: Extra-abdominal view. B: Intra-abdominal view. |

By definition, no clinically detectable hernia will be present during examination. The need for a thorough examination by an experienced examiner with an understanding of the anatomy cannot be over-emphasized. The physical examination includes a thorough assessment of the pelvic musculature and plain radiographs to assure no significant bony pathology is present. Tenderness is commonly seen over the conjoined tendon, pubic tubercle, and the mid inguinal region (13). In some cases, a tender internal inguinal ring is noted. While the diagnosis of an inguinal hernia is not typically missed as a result of the significant radiation into the groin, this needs to be assessed to assure that it is not a more common inguinal hernia. The most common clinical findings have been pain with resisted leg adduction in 88%, while only 22% had pubic tenderness (9). Commonly positive findings include pain with a resisted sit-up and pain reproduction with a valsalva maneuver.

Imaging modalities are typically employed including plain radiographs in order to evaluate for the possibility of either a different or coexisting pathology. Most commonly, there is a significant overlap with osteitis pubis as well as chronic adductor musculature irritation. In addition, herniography may be used as a treatment to evaluate the area and has had some support in the recent literature (14,15). In a study by Hamlin and Kahn (14) 333 consecutive herniographic studies were performed (14). An equivocal physical examination was the most common reason for requesting a herniogram. In 56 of the 57 patients who came to operation, the herniogram and the physical examination were concordant.

In a study by Sutcliffe et al. (15) a prospective study of 112 patients undergoing herniorrhaphy were evaluated over a 5-year period. In this study 30 hernias were diagnosed with one false positive and one false-negative examination, thus giving herniography a sensitivity of 96.6% and a specificity of 98.4%. There were no complications noted with the herniographic procedures.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also been employed in these difficult patients (16). In one study, the MRI findings of athletic pubalgia were delineated in 32 athletes studied with T1 weighted and T2 weighted as well as STIR images. The abnormalities found included pubic symphysis abnormalities, abdominal wall defects, and musculature abnormalities including rectus abdominis, pectineus, and adductor muscle groups. The authors felt that pubalgia, although a complex process and frequently multifactorial, could be delineated with MRI. More importantly it was felt that MRI could alter the surgical approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree