External Fixation of the Pelvis

Stephen A. Kottmeier

Brian Campfield

John C. P. Floyd

Nicholas Divaris

DEFINITION

Pelvic instability is defined as inability of the pelvis to assume physiologic loads without displacement and functional compromise.

Pelvic external fixation can serve several different purposes depending on hemodynamic and pelvic structural instability.

Early external fixator application during resuscitative acute phase management can serve to control intrapelvic hemorrhage.9

External fixation of the pelvis may confer sufficient provisional stability to some injury patterns to facilitate patient mobilization. It may, however, prove inadequate in achieving long-term goals in the absence of additional surgical stabilizing efforts.

With certain rotationally unstable yet vertically stable patterns, external fixation of the pelvis or an internalized anterior fixator may serve as definitive management.

ANATOMY

The pelvis provides structural continuity between the axial skeleton and lower extremities.

The pelvis affords protection and passage for genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and neurovascular structures.

Life-threatening massive hemorrhage, a complication of pelvic injury, can be of arterial (branches of the iliac system), venous plexus, or fracture surface origins.

Additional concerns when treating pelvic ring trauma include injury to the lumbosacral and coccygeal nerves and male urethra.

The anterior portion of the pelvic ring assumes minimal weightbearing function and affords little pelvic ring stability.

The pelvic ring is made up of the sacrum and paired innominate bones. Ligamentous, rather than osseous, support is the sole source of stability to the pelvis.

Stability of the pelvis is particularly dependent on the tension band of the posterior weight-bearing sacroiliac complex (comprising the anterior sacroiliac ligaments, the interosseous ligaments, and the posterior sacroiliac ligaments) in addition to the iliosacral ligaments within the pelvic floor (sacrospinous and sacrotuberous). The iliolumbar ligaments confer additional stability between the axial skeleton (L5 transverse process) and the hemipelvis (ilium).

PATHOGENESIS

Pelvic injury patterns (osseous or ligamentous) are determined by the direction, point of application, and magnitude of applied forces.

Applied forces can be simplified into anteroposterior (AP) compression, lateral compression, and vertical shear. Actual forces and accordingly mechanism of injury are likely more complex.

Resultant instability patterns are categorized as (1) vertically and rotationally stable, (2) rotationally unstable and vertically stable, and (3) rotationally and vertically unstable.

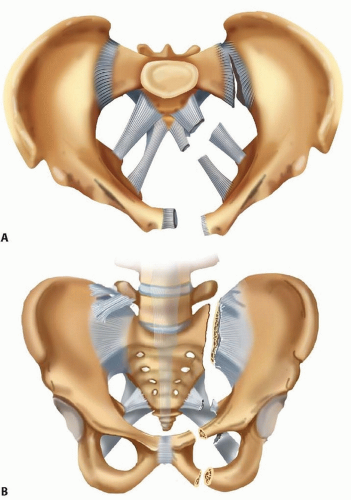

AP compression and hemipelvic rotational forces tend to result in injury to the “anterior ligamentous” complex (severity order: symphysis pubis, ischiosacral ligaments, anterior sacroiliac ligament). The integrity of the posterior tension band is preserved and vertical stability accordingly maintained (FIG 1A). Depending on the severity of injury to the anterior ligamentous complex, rotational instability may ensue.

Lateral compression injuries, depending on severity, may result in internal collapse of the pelvis. Ligaments both anteriorly and posteriorly generally remain intact. Osseous injuries both anteriorly and posteriorly are typically stable impaction variants. Occasionally, internal rotatory instability is sufficient to warrant surgical stabilization (external or internal fixation).

Vertical instability implies disruption of the posterior tension band of the pelvic ring. This may be of osseous, ligamentous, or combined origin. Division of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments in the presence of intact posterior ligaments will render a pelvis rotationally unstable. Further division of the posterior ligaments of the sacroiliac complex will result in both rotational and vertical instability. The involved hemipelvis is unstable in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes (FIG 1B).

Any injury mechanism (AP compression, lateral compression, vertical shear) may result in complete (vertical and rotational) instability if the magnitude of force is sufficient.

NATURAL HISTORY

Life-threatening hemorrhage associated with pelvic fractures may be intrapelvic or extrapelvic. Identifying the source of bleeding may be challenging.27 In the absence of extrapelvic and intraperitoneal sources, external fixation of the pelvis may prevent life-threatening exsanguination.

Early sheeting (circumferential external compression) may offer an initial beneficial hemodynamic response. Suspected sustained hemorrhage of indeterminate source may be intrapelvic arterial in origin.2 This may respond favorably to angiographic transcatheter embolization.

Exploratory laparotomy, from the standpoints of role and timing, remains controversial.

Imaging findings, results of diagnostic peritoneal lavage (if indicated), and response to fluid resuscitation must be considered before exposing the unstable trauma victim to the potential negative effects of abdominal exploration (decompression of intrapelvic tamponade, among others).

Pelvic fractures associated with violation of the perineal, rectal, or vaginal regions must be identified immediately, and early measures directed toward preventing regional and systemic sepsis must be implemented. Appropriate soft tissue management requires early aggressive débridement and restoration of pelvic stability to facilitate wound care. External fixation is of paramount importance in many such cases, as is diverting colostomy.

Lumbosacral plexopathy may present in combination with sacral spinal canal or foraminal fractures. Pelvic reduction with restoration of stability and occasionally neurologic decompression may afford a more favorable prognosis if properly indicated and executed.23

Insufficient restoration of pelvic stability may result in complications associated with prolonged recumbency. Additional concerns include malunion and nonunion. Lower extremity limb length inequality and rotational deformity may result in functional deficits. Anterior ring injuries with significant displacement (tilt fragments) can result in sexual dysfunction, particularly in females.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The history, in terms of the mechanism of injury, offers insight into the energy of injury imparted. Force application and magnitude in turn determine pelvic injury and instability patterns as well as the type and frequency of associated injuries.7

The patient’s age may affect both physiologic reserve and bone quality. This dictates, respectively, the hemodynamic response and the energy of injury required to generate certain pelvic ring injuries.

Preexisting medical comorbidities must be ascertained, as they may have considerable impact on survivability and complications associated with both operative and nonoperative management of pelvic injuries.

Pelvic ring disruption is often accompanied by potentially life-threatening injuries to organs, vessels, and nerves within the pelvis, as well as other extrapelvic and closed cavity lesions of the abdomen, thorax, and head.

Adequate adherence and response to principles of resuscitation must be assessed and primary and secondary surveys completed.

Clinical evaluation includes inspection for abrasions, contusions, limb length discrepancy, or abnormal rotation of the lower extremities.

Palpation and manual testing for instability patterns may be pursued with caution. Stability is suggested (not confirmed) both radiographically and clinically.

Identification of any open fracture variants and those with rectal or vaginal continuity is mandatory, as mortality rates in the presence of such lesions are considerable.5

Physical examination should include the following:

Pelvic inspection to identify threatened or compromised soft tissues

Inspection of lower extremities for limb length inequality, rotational deformity, associated limb fractures or dislocations

Significant asymmetry in limb length or rotation implies rotational or vertical pelvic instability.

Further clinical examination or imaging of the limb is warranted if asymmetry is of other than pelvic origin.

Assessment of pelvic instability

Lateral compression injury is implied by internal rotation and shortening.

Vertical shear injury is implied by external rotation and shortening.

The genitourinary area is observed for regional hemorrhage. If present, it implies a urethral tear in a male and a vaginal tear in a female.

Neurologic assessment to identify deficits in voluntary sphincter control or perianal sensation. Lumbosacral plexopathy implies pelvic instability.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Imaging studies offer a static view of the pelvis. These accordingly may imply but do not confirm stability (or instability) of the pelvis.

Conventional radiography is initiated with performance of an AP radiograph of the pelvis. In the hemodynamically unstable patient, this image alone is sufficient to allow implementation of treatment.

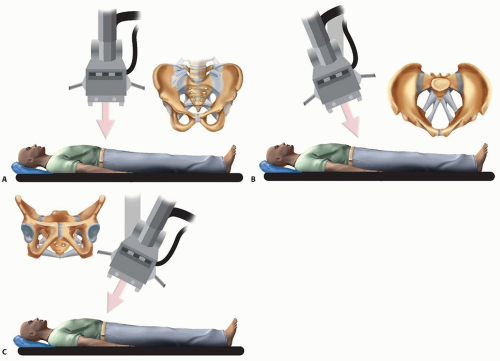

The pelvic inlet and outlet views in combination with the

AP radiograph constitute the pelvic trauma radiographic triad (FIG 2A). The inlet view (FIG 2B) best depicts axial

(most often posterior) and rotational displacement. In contrast, the outlet view (FIG 2C) best demonstrates vertical displacement.

Posterior pelvic displacement of more than 1 cm suggests posterior pelvic disruption. Symphyseal diastasis of more than 2.5 cm denotes disruption of the anterior ligament complex.

Other radiographic clues implying vertical or rotational instability include the following:

Sacrospinous ligament avulsions (ischial spine or sacral border fractures)

Iliolumbar ligament avulsion (L5 transverse process fracture)

Sacral fractures or sacroiliac joint displacement

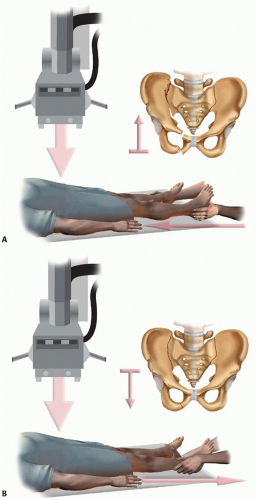

Stress radiographs (“push-pull” studies) may offer a dynamic interpretation of pelvic instability (FIG 3). Longitudinal load and traction are sequentially imparted to the lower extremity of the involved hemipelvis with manual stabilization of the contralateral extremity.

This is performed with the patient anesthetized and under

AP radiographic control.

Such maneuvers are contraindicated in the presence of lumbosacral plexopathy, hemodynamic instability, or ipsilateral lower extremity fractures.

Computed tomography (CT) serves as a valuable adjunctive study. Cross-sectional axial images characterize posterior lesions best. Sacral foraminal and central spinal canal involvement is confirmed, as is integrity of the posterior tension band. Sacral impaction as opposed to gap displacement may suggest (but does not confirm) inherent stability.

The role of diagnostic and therapeutic angiography remains controversial with regard to management pathways.4, 10, 17 External fixation of the pelvis may effectively arrest venous and osseous hemorrhage (the source of 90% of intrapelvic hemorrhage).

Sustained hemodynamic instability may suggest extrapelvic or intrapelvic arterial blood loss. In such cases, exploratory angiography may be considered and therapeutic arterial angiographic embolization performed as necessary.

Diagnostic peritoneal tap and lavage (first described in 1965) has a poorly defined contemporary role.15 Procedure performance, indications, and assay result criteria (cell count) remain ambiguous. The presence of a pelvic fracture may contribute to a false-positive result.

Current imaging technology (contrast-enhanced CT, focused abdominal ultrasound) may prove a more reliable tool to determine the likelihood of abdominal injury and the need for laparotomy.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Low-energy pelvic fractures in senescent bone

High-energy pelvic fractures in younger patients with better quality bone

Similar fracture patterns in the two groups cited earlier suggest a high magnitude of force in the younger population. This, in turn, is more commonly associated with additional injuries of concerning severity.

“Nonring” fractures: iliac crest, ischial tuberosity

Ring fractures of increasing severity and instability

Rotationally and vertically stable

Rotationally unstable and vertically stable

Rotationally and vertically unstable

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Circumferential pelvic antishock sheeting may offer comfort and enhance ring stability.24 This noninvasive method employs readily available and inexpensive materials.

Nonsurgical management is appropriate for lesions accurately deemed stable (confirmed on follow-up both clinically and radiographically).

The goals for nonsurgical and surgical management are identical. These include avoidance or correction of deformity, maintenance of stability, and pain-free function.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The role of the external fixator must be defined before application.21 By decreasing pelvic volume, it offers intrapelvic tamponade. This, in addition to diminishing fracture motion, encourages hemostasis. In this capacity, it serves as acute phase management.

It may offer provisional stabilization of some injury patterns to facilitate patient mobilization. Attempts to stabilize vertically unstable lesions with external fixation alone are inadequate (FIG 4); these injuries require staged supplemental posterior fixation. Used for this purpose, it serves as provisional stabilization.

Rotationally unstable yet vertically stable patterns may be amenable to external fixation as a source of definitive stabilization. Lesions with considerable symphyseal comminution unreceptive to anterior plating may be managed to union with external fixation, provided the posterior tension band remains functionally intact.

Preoperative Planning

The surgeon must identify associated intrapelvic, vascular, urologic, and gynecologic comorbidities.

The surgeon must confirm the patient’s neurologic status and document deficits. Soft tissues are inspected thoroughly and circumferentially.

The surgeon characterizes, if applicable, the presence and type of pelvic instability, assigning the injury pattern to a classification scheme.

The intended purpose of external fixator must be defined

(resuscitation or provisional vs. definitive stabilization).

If for purposes of provisional stabilization, the surgeon should determine the anticipated timing, sequence, and method of subsequent definitive stabilization.

Frame design and pin location are selected (anterior iliac crest, supra-acetabular, posterior C-clamp) based on the pelvic injury pattern, the patient’s hemodynamic status, the available imaging, and surgeon familiarity.

An immediate presurgical pelvic radiograph is obtained to assess the impact of retained bowel gas or contrast on imaging capability (if required).

Positioning

The patient is placed supine on a radiolucent table.

Adequacy of imaging and efficacy of closed reduction maneuvers are confirmed.

Preparation is done from the umbilicus to the anterior thighs, including both iliac crests.

One or both lower extremities are included circumferentially as required to effect rehearsed closed reduction maneuvers.

Approach

Adequate fixation and accordingly proper pin placement are the principal requirements for restoring pelvic stability when applying an external fixator.

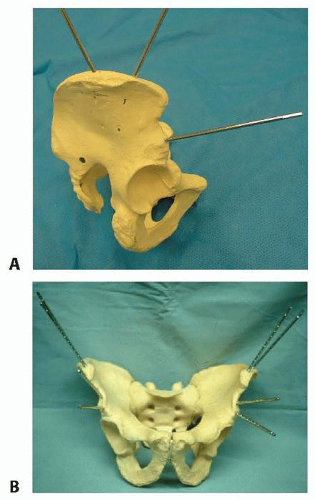

Pins for purposes of anterior pelvic external fixation may be placed either in the anterior iliac crest or in the supraacetabular region (FIG 5).

Ease of insertion is an important attribute when applying a resuscitation frame.

FIG 5 • The anterior hemipelvis offers two sites for pin insertion: the iliac crest (superiorly) and the supra-acetabular region (more inferiorly). A. Profile view. B. Frontal view.

Pin placement within the iliac crest is more expeditiously performed and lacks significant regional anatomic hazards.

On occasion, this area may be compromised by soft tissue concerns or proximity to fracture planes.

In such cases, pin placement within the supra-acetabular region is an option.

Pins and frames in this lower position may offer improved access to the abdomen and, unlike pins placed within the iliac crest, are less irritating to anterolateral abdominal soft tissues.19

In an obese patient, these pins (supra-acetabular) may be better tolerated and less prone to loosening and infection.

The dense bone of the supra-acetabular region offers stability of fixation as good as or better than the iliac crest.

Some authors investigating the biomechanical performance of these pins (supra-acetabular) demonstrated superior purchase within bone and diminished displacement of posterior portions of the pelvic ring.12

Because supra-acetabular pin insertion is more time consuming and instrumentation and fluoroscopy dependent, its role as a resuscitative measure is limited.

The pelvic antishock clamp (C-clamp) is a posteriorly (or trochanteric) applied device that may offer greater stability to vertically unstable fractures than anteriorly applied frames (FIG 6).1, 11 It is designed for the emergent treatment of unstable pelvic ring injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree