Exercise considerations for aging adults

Pamela Reynolds

Introduction

All exercise requires the coordinated function of both the heart and lungs, as well as the peripheral and pulmonary circulations, to transport nutrients and exchange the oxygen required to support muscular contraction and movement. Age-related cardiovascular and pulmonary changes have been described earlier (see Chapters 6, 7 and 9). This chapter primarily presents an overview of endurance or aerobic exercise considerations for normal age-related changes. Other chapters discuss appropriate exercise interventions for specific cardiovascular and pulmonary pathologies (see Chapters 42–45) as well as additional information related to muscle strengthening (see Chapter 16).

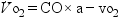

The availability of oxygen and the body’s ability to utilize it during physical activity is a key performance factor of therapeutic exercise and related interventions. The Fick equation,  , concisely represents this concept, where

, concisely represents this concept, where  represents the volume of oxygen/min/unit of body weight that is utilized during a specific activity; CO is cardiac output; and a−vO2 is arteriovenous difference.

represents the volume of oxygen/min/unit of body weight that is utilized during a specific activity; CO is cardiac output; and a−vO2 is arteriovenous difference.  is the maximum amount of oxygen that the body can obtain and utilize for any physical activity. This can also be described as a person’s physical fitness level or functional capacity. The amount of oxygen that the body can obtain and effectively utilize is dependent on two factors: (i) the delivery of oxygen-rich blood to metabolically active tissues, especially muscles; and (ii) the ability of these tissues to extract and utilize the delivered oxygen. The delivery factor or central component is dependent on CO, which is a product of heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV). The peripheral component is represented by the arteriovenous difference (a–vO2), or the difference between the oxygen content of the arterial blood entering the metabolically active tissue and the amount of oxygen left in the venous blood that is returned to the heart. Cardiopulmonary dysfunctions are usually a result of impairments in the delivery system (McArdle et al., 2011).

is the maximum amount of oxygen that the body can obtain and utilize for any physical activity. This can also be described as a person’s physical fitness level or functional capacity. The amount of oxygen that the body can obtain and effectively utilize is dependent on two factors: (i) the delivery of oxygen-rich blood to metabolically active tissues, especially muscles; and (ii) the ability of these tissues to extract and utilize the delivered oxygen. The delivery factor or central component is dependent on CO, which is a product of heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV). The peripheral component is represented by the arteriovenous difference (a–vO2), or the difference between the oxygen content of the arterial blood entering the metabolically active tissue and the amount of oxygen left in the venous blood that is returned to the heart. Cardiopulmonary dysfunctions are usually a result of impairments in the delivery system (McArdle et al., 2011).

Exercise considerations

When developing an exercise program or prescription, it is important to consider the following:

• medical screening or clearance

• baseline functional capacity

• consideration of the mode, intensity, frequency and duration

• safety

Screening and informed consent

Aging has some immutable factors that increase a person’s risk for exercise. Many disorders do not demonstrate significant clinical signs during regular daily activities but they may become evident during exercise. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM, 2010) identifies men and women as having low cardiovascular disease if they are asymptomatic and have one or less risk factor listed in Table 39.1. Note that age is a positive risk factor for men≥45 years and women≥55 years. Men and women who are asymptomatic and have two or more cardiovascular risk factors are categorized as having moderate risk. Any individual who has known or symptomatic cardiovascular, pulmonary, of metabolic disease or has one or more of the symptoms listed in Box 39.1, is considered at high risk for cardiovascular disease.

Table 39.1

| Positive Risk Factors | Defining Criteria |

| Age | Men≥45 yr, Women≥55 yr |

| Family history | Myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or sudden death before 55 yr of age in father or other male first-degree relative, or before 65 yr of age in mother or other female first-degree relative |

| Cigarette smoking | Current cigarette smoker or those who quit within the previous 6 months or exposure to environmental tobacco smoke |

| Sedentary lifestyle | Not participating in at least 30 min of moderate intensity (40%–60% V˙O2R) physical activity on at least 3 days of the week for at least 3 months |

| Obesitya | Body mass index≥30 kg/m2or waist girth>102 cm (40 inches) for men and>88 cm (35 inches) for women |

| Hypertension | Systolic blood pressure≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic≥90 mmHg, confirmed by measurements on at least two separate occasions, or on antihypertensive medication |

| Dyslipidemia | Low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) cholesterol≥130 mg/dl (3.37 mmol/l) or high density lipoprotein (HDL-C) cholesterol<40 mg/dl (1.04 mmol/l) or on lipid lowering medication. If total serum cholesterol is all that is available use≥200 mg/dLl (5.18 mmol/l) |

| Prediabetes | Impaired fasting glucose (IFG)=fasting plasma glucose≥100 mg/dl (5.50 mmol/l) but<126 mg/dl (6.93 mmol/l) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)=2-hour values in oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)≥140 mg/dl (7.70 mmol/l) but<200 mg/dl (11.00 mmol/l) confirmed by measurements on at least two separate occasions |

| Negative Risk Factor | Defining Criteria |

| High-serum HDL cholesterol | ≥60 mg/dl (1.55 mmol/l) |

aProfessional opinions vary regarding the most appropriate markers and threshold, for obesity; therefore, allied health professionals should use clinical judgment when evaluating this risk factor.

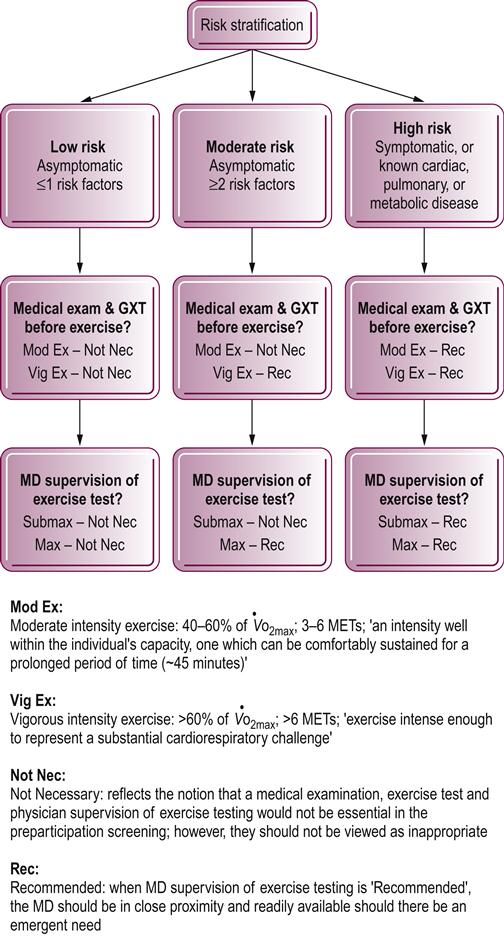

After establishing risk category, the recommendation for medical examination and need for physician supervision during graded exercise testing can be determined. See Figure 39.1 for this information from the ACSM.

For the elderly in the moderate-risk category only, who plan to engage in moderate exercise training, medical screening is not necessary. Moderate exercise training entails activities requiring three to six METs (metabolic equivalents). However, although training at this level may be designated as screening ‘not necessary’, it should not be deemed inappropriate. Examination and evaluation should always guide a clinician’s decisions in this area (ACSM, 2010). It is also important to identify the medications that a patient is taking. Regular use of cardiovascular drugs, tranquilizers, diuretics and sedatives can affect the physiological response to exercise.

Patient/clients who are receiving skilled therapeutic rehabilitation services regularly sign informed consent forms before treatment. Informed consent is an important ethical and legal consideration, particularly for health promotion services that may not be covered by insurances. The participant should know the purposes and risks associated with an exercise program and testing.

Baseline functional capacity

Establishing a baseline functional capacity is essential for those who intend to participate in an exercise program. As the individual progresses through the exercise program, comparison of the initial exercise test with subsequent tests will provide feedback regarding the individual’s success in the program. Such assessments have been shown to play a significant role in decreasing attrition rates in exercise programs.

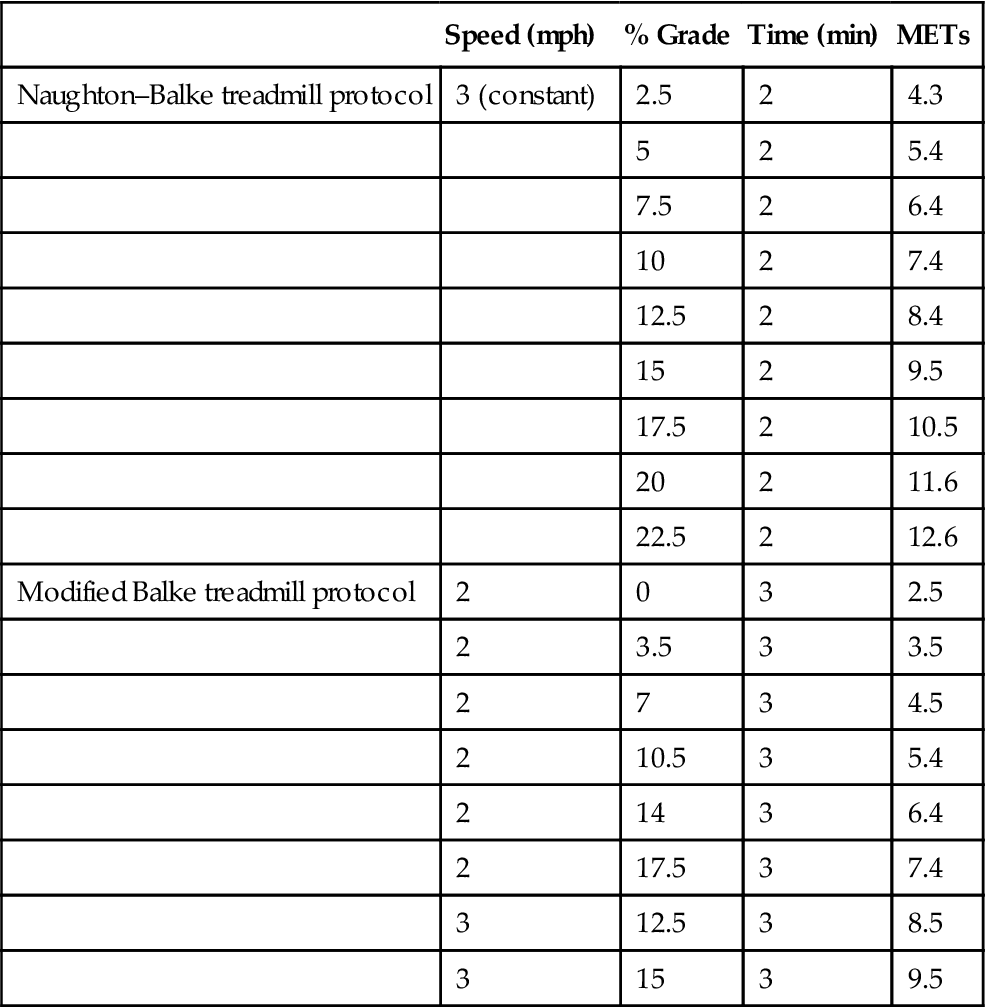

The selection of a graded exercise test should take into consideration the purpose of the test, desired outcome and the individual being tested. A graded exercise test protocol must effectively challenge the patient/client but not be too aggressive. Tests can be categorized into single-stage and multistage tests. An example of a single-stage exercise test is the 6 minute walk test. It requires a measured course. A seldom used indoor corridor is recommended, with cones indicating turning points. The measure is the distance walked in 6 minutes. The person may use an assistive device and rest as often as necessary during this cycle of time (Roy et al., 2013). Multistage exercise tests include treadmill and cycle ergometer. The Naughton–Balke, modified Balke (Table 39.2) and modified Bruce treadmill protocols (Table 39.3) are recommended for deconditioned individuals with cardiovascular or pulmonary disease (ACSM, 2010; Watchie, 2010).

Table 39.2

Naughton–Balke and modified treadmill protocols

| Speed (mph) | % Grade | Time (min) | METs | |

| Naughton–Balke treadmill protocol | 3 (constant) | 2.5 | 2 | 4.3 |

| 5 | 2 | 5.4 | ||

| 7.5 | 2 | 6.4 | ||

| 10 | 2 | 7.4 | ||

| 12.5 | 2 | 8.4 | ||

| 15 | 2 | 9.5 | ||

| 17.5 | 2 | 10.5 | ||

| 20 | 2 | 11.6 | ||

| 22.5 | 2 | 12.6 | ||

| Modified Balke treadmill protocol | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 3 | 3.5 | |

| 2 | 7 | 3 | 4.5 | |

| 2 | 10.5 | 3 | 5.4 | |

| 2 | 14 | 3 | 6.4 | |

| 2 | 17.5 | 3 | 7.4 | |

| 3 | 12.5 | 3 | 8.5 | |

| 3 | 15 | 3 | 9.5 |

From ACSM, 2010, Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 8th edn, with permission from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Table 39.3

Modified Bruce treadmill protocols

| Stage | Speed MPH | Elevation | METs | |

| M | S | Duration=3 minutes each stage | ||

| 1 | 1.7 | 0% | 2 | |

| 2 | 1.7 | 5% | 3 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1.7 | 10% | 5 |

| 4 | 2 | 2.5 | 12% | 7. |

| 5 | 3 | 3.4 | 14% | 10 |

| 6 | 4 | 4.2 | 16% | 13 |

| 7 | 5 | 5.0 | 18% | 16 |

| 8 | 6 | 5.5 | 20% | 19 |

| 9 | 7 | 6.0 | 22% | 22 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree