Ewing Tumor

Ewing tumor is a distinctive, small, round cell sarcoma that was, until recently, considered one of the most lethal of all bone tumors. It has been the subject of controversy in the literature because of the somewhat nonspecific histologic characteristics of the tumor, which is composed of solidly packed small cells. Previously, the controversy involved whether all Ewing sarcomas represented metastatic neuroblastomas or not. Another controversy involved the question as to whether the so-called primitive neuroectodermal tumor is distinctly different from Ewing sarcoma. Formerly, some of the small cell osteosarcomas, most of the malignant lymphomas, and even some benign conditions, such as eosinophilic granulomas, were at times classified with Ewing tumor.

A practical working definition is to regard as Ewing tumors all highly malignant, small, round-to-oval cell sarcomas that have the clinical and radiographic characteristics of a primary osseous lesion. Inherent in this concept is the exclusion of cytologically incompatible lesions such as myeloma, malignant lymphoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Production of a chondroid or osteoid matrix by the neoplastic cells likewise excludes Ewing sarcoma. Similarly, true spindling of the nuclei is incompatible with the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma. However, artifactual spindling, especially at the periphery of the tumor, produced by crushing at the time of biopsy, has to be distinguished from true spindling of tumor cells. It is sometimes impossible to differentiate a biopsy specimen of a metastatic malignant tumor such as a neuroblastoma, small cell carcinoma of the lung, or even a leukemic infiltrate from a specimen of Ewing tumor, even after critical histologic study, according to modern concepts. Immunoperoxidase stains, however, can effectively rule out metastatic carcinomas and lymphomas and leukemias.

There has been much speculation on the possible origin of the cells that comprise Ewing tumor. Although previously the tumor was considered to arise from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, it is now considered a tumor of neuroectodermal origin.

Although Ewing tumor and malignant lymphoma can be distinguished histologically in most cases, an occasional tumor has a histologic appearance that is midway between the two. In the present series, some tumors contain cells that were larger and somewhat more irregular than those of classic Ewing tumor. Their clinical characteristics and prognosis made it practical to include them with Ewing tumors rather than attempt to define a new tumor type. These have been considered to be large cell or atypical Ewing tumors.

A soft tissue counterpart of Ewing sarcoma is occasionally encountered.

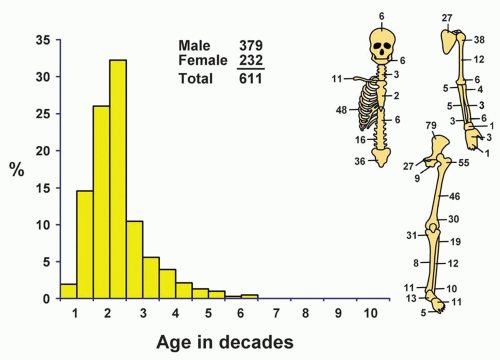

SEX

Ewing tumor has a distinct predilection for males (62%).

AGE

The patients affected by this tumor are, on average, younger than those affected by any other primary malignant tumor of bone. Just over 58% of all patients were in the second decade of life, and approximately 75% were in the first two decades of life. Twelve patients were younger than 5 years. The youngest patient was 17 months. This small group included six females and six males. The oldest patient was 59 years old. Four patients were older than 50 years, and all were males. When confronted with the problem of Ewing tumor in a patient who is beyond the third decade of life, one must be especially careful to exclude metastatic carcinoma. Similarly,

in a very young patient, metastatic neuroblastoma and even acute leukemia must be considered.

in a very young patient, metastatic neuroblastoma and even acute leukemia must be considered.

LOCALIZATION

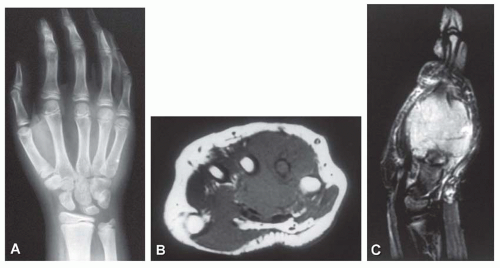

Most Ewing tumors are in the extremities, but any bone of the body may be involved. Any portion of a long tubular bone may be affected. Although the proximal and distal metaphyses of long bone are more commonly affected, the shaft is involved more often than in other types of sarcomas. The lower extremities and pelvic girdle accounted for 59.6% of the tumors in the Mayo Clinic series. Although 29 lesions involved the small bones of the feet, only 5 lesions involved the small bones of the hands, 3 involved the metacarpals, 1 each involved a carpal and a phalanx. Sixty-one lesions involved the spinal column, including the sacrum. The maxilla was not involved in any case, but there were six examples of lesions in the mandible and six in the skull bones. Three patients had two skeletal sites of involvement at presentation as follows: one patient had tumors in the left ischium and right ilium, one had lesions in a rib and the ilium, and one had lesions of a metatarsal and the tibia. In addition, three patients presented with disease involving multiple bones. One tumor appeared to arise on the surface of bone.

SYMPTOMS

Pain and swelling are the most common symptoms of Ewing tumor. Pain is the first symptom in more than half the patients. Pain may be intermittent at first, and it tends to increase in severity with time. Although swelling in the region of the tumor is common by the time the patient seeks medical advice, it is rarely the first symptom. Pathologic fracture is unusual. The typical patient has had symptoms for several months before seeking medical care. In this series, the survival of patients whose symptoms lasted for 6 months or longer did not differ from that of patients who had symptoms of a shorter duration.

PHYSICAL AND LABORATORY FINDINGS

Most patients have a palpable, tender mass, and some have dilated veins over the tumor. Patients with Ewing tumor sometimes have an elevated temperature and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, often associated with secondary anemia and sometimes with leukocytosis. These findings may suggest that the osseous lesion has an inflammatory origin. When the lesion is associated with systemic features, the prognosis is even worse than average.

Neuroblastoma with metastasis to bone, simulating Ewing sarcoma, can be diagnosed reliably in most cases with qualitative and quantitative determination of catecholamine metabolites in the urine. One patient in this series had bilateral retinoblastoma, and another patient had a brother who also had Ewing tumor. In one patient, carcinoma of breast developed 13 years after treatment of Ewing tumor of the sacrum.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

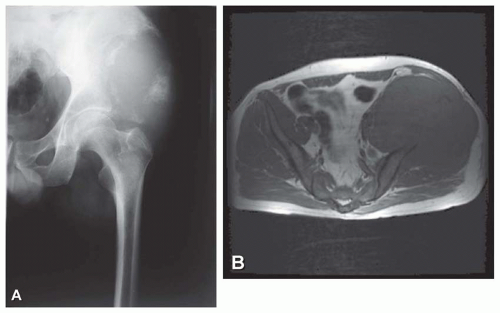

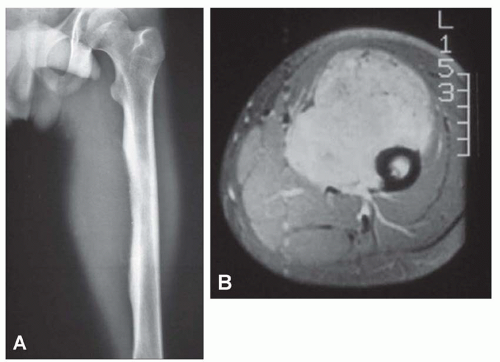

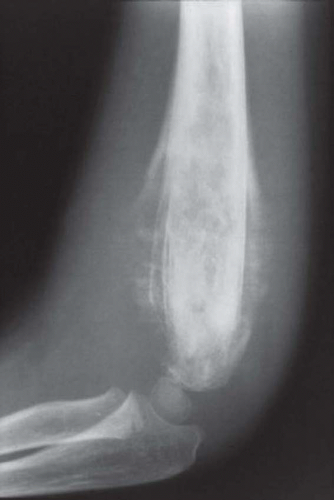

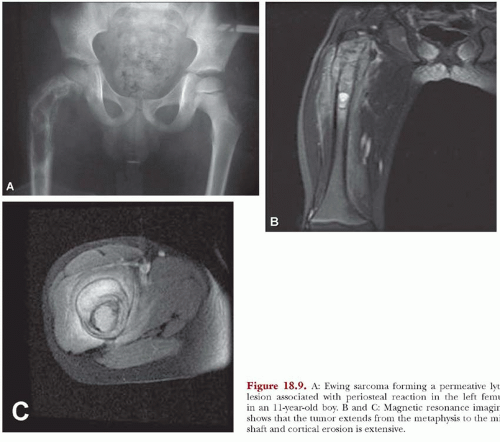

Ewing tumor tends to be extensive, sometimes involving the entire shaft of a long bone. Even so, generally more bone will be found pathologically involved than was obvious on the radiograph. Lytic destruction is the most common finding, but there may be regions of density due to stimulation of new bone formation. As the tumor bursts through the cortex, which may show only minimal radiographic changes, it often elevates the periosteum gradually. This elevation produces the characteristic multiple layers of subperiosteal reactive new bone, which produces the onionskin appearance of Ewing tumor (Fig. 18.2). Radiating spicules from the cortex of an affected bone are not uncommon, a fact that complicates the differentiation from osteosarcoma. This differentiation may be especially difficult when the lesion involves a flat bone such as the ilium. Occasionally, Ewing tumor expands the affected bone and may even superficially resemble a cyst (Figs. 18.2, 18.3, 18.4, 18.5 and 18.6).

A rare example of Ewing sarcoma may have little or no medullary component. A few tumors are almost completely in a juxtaosseous position and show little cortical destruction. Edeiken has stressed that saucerization of the exterior surface of the cortex is an early and characteristic sign of tumors presenting subperiosteally (Fig. 18.7).

Figure 18.2. Ewing sarcoma involving the proximal humerus in a 15-year-old boy. Pronounced periosteal new bone formation produces an “onionskin” appearance. |

Figure 18.3. Ewing sarcoma extensively involving the radius in an 8-year-old boy. The lesion has a permeative pattern of bone destruction. |

Figure 18.4. Ewing sarcoma involving the distal humerus. There is extensive periosteal new bone formation. |

Experienced observers have concluded that although Ewing tumor can sometimes be diagnosed with a high degree of assurance on the basis of its radiographic features and although the tumor very often produces features that are virtually pathognomonic of malignant bone tumor, several conditions can produce similar features. When the tumor produces a permeative destructive process, the differential diagnosis involves metastatic carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, and osteomyelitis. When the lesion produces an area of geographic destruction, other malignant tumors, including osteosarcoma, are included in the differential diagnosis.

Modern imaging techniques such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging do not produce images that are diagnostic of Ewing tumor. However, both of these modalities are superior to plain radiographs in defining the extent of the disease, both intermedullary and in the soft tissues. The images are especially useful in establishing the relationship of the neoplasm with the neurovascular bundle. This information may be critical in planning surgery (Figs. 18.5, 18.8, & 18.9).

GROSS PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

Solid masses of viable tumor are characteristically gray-white, moist, glistening, and sometimes translucent. They may have an almost liquid consistency, which may mimic pus. This appearance may result in the entire specimen being sent to microbiology for culture, with disastrous results. The tumor frequently invades bone beyond the limits indicated on the radiograph. Zones of necrosis, hemorrhage, and even cyst formation are common. The neoplastic tissue is often admixed with proliferating bony and fibrous tissue in the periosseous regions (Figs. 18.10, 18.11, 18.12, 18.13 and 18.14).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|