Evaluation of pain in older individuals

John O. Barr

Introduction

Pain is the symptom that most commonly prompts individuals to seek healthcare, and it has come to be recognized as a ‘fifth vital sign’ (Molony et al., 2005). Over 80% of older adults have at least one chronic condition that results in some type of discomfort, including pain (Burke & Jerret, 1989). While arthritis is the most common cause of pain, other conditions that result in chronic pain for the elderly include cancer, compression fracture, degenerative disc disease, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, hip fracture, postherpetic or trigeminal neuralgia and stroke. Older individuals have noted the three most common sites of pain to be the back, leg/knee or hip, and other joints (Abdulla et al., 2013). In outpatient settings, older adults receive less adequate analgesia for moderate to severe acute pain (Moskovitz et al., 2011). During the last 2 years of life, pain is experienced by more than 25% of the elderly, with the prevalence increasing during the last 4 months of life (Smith et al., 2010). Across the continuum from acute postoperative to chronic persistent pain, older people experience less than optimal pain management. Unfortunately, older individuals frequently believe that pain is an inevitable consequence of aging that must simply be endured. Upon being questioned by a health professional, they may deny being in pain out of fear of medical procedures and related expenses, loss of autonomy and possible institutionalization.

The atypical presentation of pain in older persons complicates its clinical evaluation. The cardinal signs of inflammation, including pain, redness, elevated temperature and swelling, are less pronounced in the elderly. For example, acute myocardial infarction can occur without significant pain, while conditions such as appendicitis, bowel gangrene, peptic ulcers and pneumonia may result in only mild discomfort. Instead of producing pain, these conditions may contribute to other behavioral signs such as confusion and fatigue. Conversely, pain that is less common in the elderly, such as headache, can signal serious medical problems such as cerebrovascular accident and temporal arteritis (Papadakis et al., 2013). Inadequate assessment and undertreatment of pain are two primary problems for older individuals (Taylor et al., 2005).

Evaluation of pain

Key international organizations (e.g. World Health Organization, 2007), professional organizations (e.g. the American Geriatrics Society, 1998, 2000, 2009) and regulatory agencies (e.g. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 2013) have advocated for improved assessment and treatment of pain experienced by older people. Appropriate evaluation of pain involves the synthesis of information derived from the patient’s history, subjective interview, objective physical examination and special tests (e.g. laboratory, imaging, electroneuromyography etc.). The evaluation should clarify the underlying basis for pain and guide therapeutic interventions or result in referral for other specialized healthcare services. Importantly, this evaluation provides baseline information needed to determine the effectiveness of treatment. Periodic re-evaluation allows assessment of the response to treatment, including adverse reactions. The evaluation of pain is unfortunately complicated by its very personal and subjective character. The manner in which an individual reports pain is related to a range of factors that include age, cognitive status, gender, personality, ethnic/cultural background, behavioral needs and past pain experiences.

The patient/client history should include information about current medical conditions and medications that are prescribed: over-the-counter and natural or home remedies. Past interventions that have been both successful and unsuccessful in controlling pain should also be noted. It may be possible to determine patient expectations for or biases against certain interventions, and also to gain further insight as to why a prior treatment was a success or a failure. For example, a previous lack of patient education may have contributed to poor adherence to a prior pain management strategy.

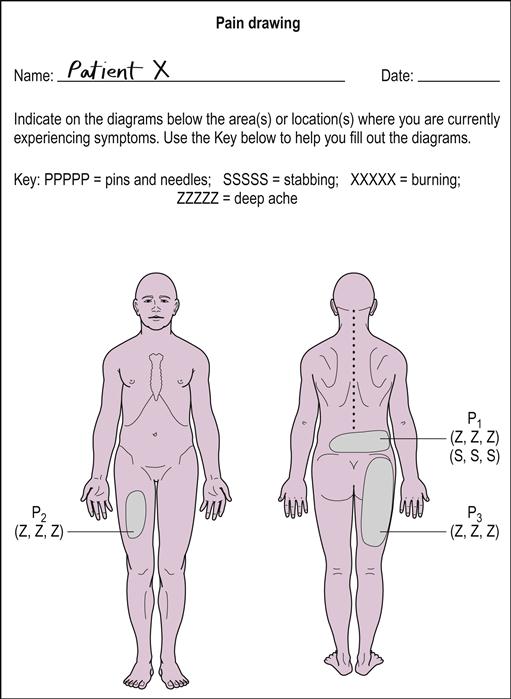

The individual should be given the opportunity to freely verbalize complaints of pain and related symptoms (e.g. aching, burning, fatigue, joint locking, joint warmth, paresthesia, stiffness etc.). The clinician should then direct specific questions concerning the onset, occurrence (e.g. at rest vs. activity), intensity (current vs. greatest and least during a specific time period), quality, distribution and duration of pain. Situations that aggravate and relieve pain should be identified (e.g. types of movement, postures, rest etc.). The patient can mark a body diagram to document the location(s) and quality of their pain (Fig. 66.1). Assessment of behavioral indicators of pain is especially useful for documenting the presence of pain in individuals with limited verbal or impaired cognitive abilities (Box 66.1).

The objective examination should focus on physical signs or impairments thought to be associated with a given pain problem (e.g. edema, gait parameters, joint tenderness, muscle strength and endurance, posture, pulmonary functions, range of motion, skin temperature, tissue healing, tolerance to palpation etc.). Typically, there are reduced levels of activity and functional independence, so it is important to evaluate physical function including activities of daily living (ADL) and physical performance related to occupational and recreational pursuits. It should be recognized that some ADL assessment tools (e.g. the Katz Index of ADL or the Barthel Index) do not represent an adequate range of functional activities for community-active older people, while other tools require too high a level of functioning for some institutionalized cognitively impaired elderly individuals (e.g. the Physical Performance Test). Observational analysis of simulated ADL performance has been found to be sensitive and valid in assessing pain behavior in older people with chronic low back pain (Weiner et al., 1996). Importantly, functional limitations should be translated into treatment plan outcome goals.

Pain assessment tools

A number of pain assessment tools have been developed over the years in the attempt to document clinical pain more objectively. The most basic tool for the assessment of pain intensity is the Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS; also called the ‘Verbal Rating Scale’). Patients are instructed to rate their pain intensity as being ‘none’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’, or ‘unbearable’. This scale is preferred by individuals who find it easy to understand, resulting in low failure rates for their scoring. Lack of sensitivity in detecting changes based on the limited number of rating categories is the primary limitation of this type of scale. The Iowa Pain Thermometer (IPT) combines an expanded VDS and a pain thermometer (PT) (Taylor et al., 2005).

The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS; also call the Pain Estimate or PE) requires patients to rate the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10, or 0 to 100 (‘0’ indicating no pain, and endpoints of ‘10’ or ‘100’ representing the worst possible pain that could ever be imagined). Understanding the definitions related to these endpoints is critical. If a patient mistakenly believes that a rating of ‘100’ is to indicate ‘the worst pain I’ve ever had’, pain that is even more severe the next day could not be properly rated. The primary advantages of this approach are that it is easy to understand and that ratings can be done verbally.

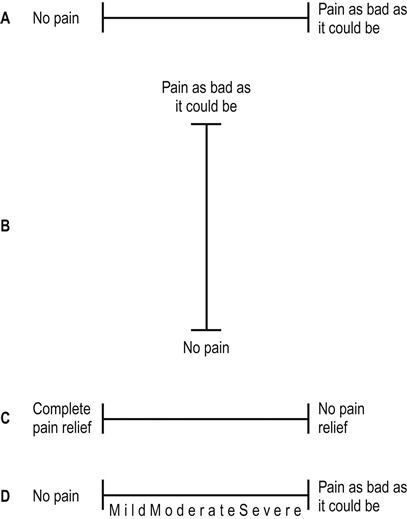

The Visual Analogue Pain Scale (VAPS) employs a horizontal 10 cm line with ‘no pain’ at the left and ‘pain as bad as it could be’ at the right (Fig. 66.2). Patients mark one location on the line corresponding to the intensity of their pain. This scale may also be vertically oriented. An alternative format requires the rating of pain relief, employing scale anchors of ‘complete pain relief’ and ‘no pain relief’. A major limitation of visual analogue scales is that they rely on vision and motor control, which may be limited in some older patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree