Entamoeba Histolytica

Bradley Howard Kessler

Amebiasis is defined as infection with Entamoeba histolytica, with or without overt clinical symptoms. Distribution of the disease is worldwide, affecting as much as 10% of the population. The highest prevalence is seen in developing areas and tropical regions. It has been estimated that approximately 1% to 5% of U.S. residents who have never traveled outside the United States have amebiasis; most of these are asymptomatic carriers. Severe disease, such as ulcerative amebic colitis or liver abscess, is relatively rare.

ETIOLOGY

Two forms of the protozoan parasite E. histolytica, cysts and trophozoites, are found in stool specimens. Trophozoites are motile, variably shaped organisms that are 7 to 30 μm in diameter and have a single nucleus and a granular, vacuolated cytoplasm. Trophozoites characteristically produce pseudopodia, which are finger-like projections from the main body that

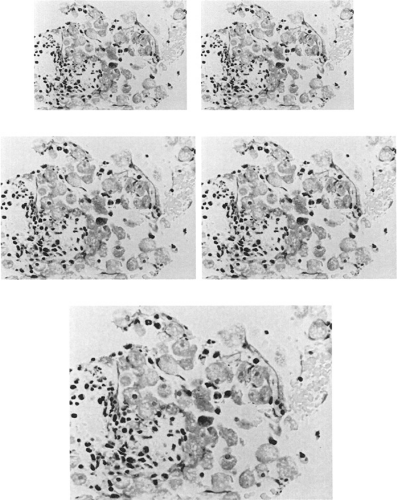

participate in both motility and phagocytosis. This form of the parasite may be found in patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic amebiasis. In individuals with symptomatic amebiasis, the pathogenic trophozoites may contain ingested red blood cells in endoplasmic vacuoles and can be as large as 60 μm in diameter (Fig. 216.1). Phagocytosis may be an important virulence factor. Specific isoenzyme migration patterns or zymodemes obtained from starch gel electrophoresis are indirect markers of virulence. Certain strains of nonpathogenic E. histolytica, now classified as E. dispar, are associated only with asymptomatic carriage.

participate in both motility and phagocytosis. This form of the parasite may be found in patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic amebiasis. In individuals with symptomatic amebiasis, the pathogenic trophozoites may contain ingested red blood cells in endoplasmic vacuoles and can be as large as 60 μm in diameter (Fig. 216.1). Phagocytosis may be an important virulence factor. Specific isoenzyme migration patterns or zymodemes obtained from starch gel electrophoresis are indirect markers of virulence. Certain strains of nonpathogenic E. histolytica, now classified as E. dispar, are associated only with asymptomatic carriage.

FIGURE 216.1. Trophozoite with hemophagocytosis. (Courtesy of Pathology Department of Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center.) |

The nonmotile cyst form is similar in size to the trophozoite but may contain as many as four nuclei. Infection occurs only with ingestion of cysts. On ingestion, after excystation in the small bowel, each single cyst results in eight trophozoites. Encystation of the trophozoite completes the life cycle. Unlike the trophozoite, which is destroyed rapidly by external environmental conditions and gastric acid, the cysts are resistant to gastric acid and to the chlorine concentrations commonly used in domestic water purification, as well as to extreme temperature and drying. Cysts may survive outside the host for several weeks in a moist environment. Cysts excreted in the stool of infected individuals perpetuate the life cycle through fecal-oral spread.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Fifty million cases of amebiasis are recorded annually. E. histolytica is the third leading parasitic cause of death in the world. Prevalence is highest in areas with poor sanitation and inadequate water treatment. Effective forms of water treatment include boiling and filtration. Infection with pathogenic tropho-zoites is not a major clinical problem in the United States, despite prevalence rates ranging from 0.1% to 50.0% in regional and institutional surveys. Overall, in the United States prevalence rates approach 2% to 4%. Amebic infection generally is confined to certain high-risk groups, including recent long-term travelers, immigrants, and immunocompromised hosts. The invasive trophozoites cause diarrhea and dysentery in 2% to 8% of infected patients. Trophozoites that enter the bloodstream may pass to the liver or other organs and cause

abscesses. Such abscesses are found as a complication of intestinal disease in all endemic areas. Reports from endemic areas worldwide also indicate that of those children who develop amebic liver abscess, most are younger than 3 years, although amebic hepatic abscess is believed to be less common in children than in adults. Amebic abscess of the liver has been reported in 1% to 9% of patients with invasive amebiasis. Abscesses are seen more frequently in men, with the highest incidence in individuals 20 to 50 years of age.

abscesses. Such abscesses are found as a complication of intestinal disease in all endemic areas. Reports from endemic areas worldwide also indicate that of those children who develop amebic liver abscess, most are younger than 3 years, although amebic hepatic abscess is believed to be less common in children than in adults. Amebic abscess of the liver has been reported in 1% to 9% of patients with invasive amebiasis. Abscesses are seen more frequently in men, with the highest incidence in individuals 20 to 50 years of age.

Humans are the natural host and reservoir for E. histolytica. Fecal-oral transmission of cysts occurs frequently through contaminated water or foods such as vegetables. Major outbreaks occur in the United States, where disease transmission predominantly occurs by person-to-person spread. Infected food handlers play a major role in transmitting the infection. Outbreaks have been associated with pollution of the water supply by sewage. Amebic infection is common in homosexuals and infects as many as 30%, with E. dispar the predominant infecting species. Patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome often harbor multiple enteric pathogens, and amebae frequently are detected in the stool of such patients. Most of these patients probably are infected with E. dispar and therefore are usually asymptomatic. The virulence of E. histolytica in specific areas, such as South Africa, Mexico, and India, may be explained by the strain of the parasite and by the nutritional status and bacterial flora in the intestine of the host.

PATHOGENESIS AND PATHOLOGY

Invasive amebiasis occurs through a number of steps: colonization in the colonic mucous blanket, penetration or depletion of the mucous layer with disruption of the epithelial barrier, and parasite lysis of responding host inflammatory cells, followed by deeper tissue penetration. Cytopathic effects of E. histolytica on monolayers of mammalian cells in tissue culture have been well described.

The factors that determine whether ingestion of E. histolytica will produce no infection, a commensal state, symptomatic colitis, or hepatic abscess are not well defined. Some factors implicated include the strain of the organism, the ability of the organism to produce cysteine proteases and pore-forming proteins (amoebapores), the adhesiveness of the organism to epithelial cells through a galactose/N-acetyl-D-galactosamine lectin-binding protein, the ability of the organism to engulf tissue elements through phagocytosis, and the interaction of the organism with the bacterial flora that is indigenous to the gastrointestinal tract. The identity of a high-affinity intestinal epithelial cell receptor is unknown. Adherence is necessary for cytolytic activity.

The mechanism of tissue invasion is not understood clearly. Some postulate that a toxin or lytic compound from the parasite provokes a generalized inflammatory response, possibly through an epithelial cell–induced cytokine, including interleukin-8, lymphokines, and activation of nuclear factor-kappa B. Activation of human caspase 3, a molecule important for apoptosis or cell death, occurs after amebic contact. In addition to tissue destruction, trophozoites may cause diarrhea by stimulating intestinal secretion by prostaglandin production. As the process continues, classic flask-shaped ulcers with undermined edges are formed. When amebae move into the bowel wall, some may be picked up in the portal circulation and become disseminated, first to the liver and then throughout the body.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree