Endoscopic Treatment of Posterior Ankle Impingement through a Posterior Approach

Phinit Phisitkul

Annunziato Amendola

DEFINITION

Posterior ankle impingement syndrome is a clinical disorder characterized by posterior ankle pain that occurs in forced plantarflexion. It can be caused by an acute or chronic injury, with the os trigonum or trigonal process of the talus as the most offending structure.10,19

Synonyms used for posterior ankle impingement syndrome include posterior block of the ankle, posterior triangle pain, talar compression syndrome, os trigonum syndrome, os trigonum impingement, posterior tibiotalar impingement syndrome, and nutcracker-type syndrome.4,11,20,38

The os trigonum is a secondary ossification center of the talus. It mineralizes between the ages of 11 and 13 years in boys and 8 and 11 years in girls. It fuses with the posterior talus within 1 year, forming the posterolateral process, often called the Stieda or trigonal process. The os trigonum remain as a separate ossicle in 1.7% to 7% of normal feet, twice as often unilaterally as bilaterally.3,8,16,24

ANATOMY

The posterior process of the talus is composed of a smaller posteromedial process and a larger posterolateral or trigonal process flanking the sulcus for the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon.

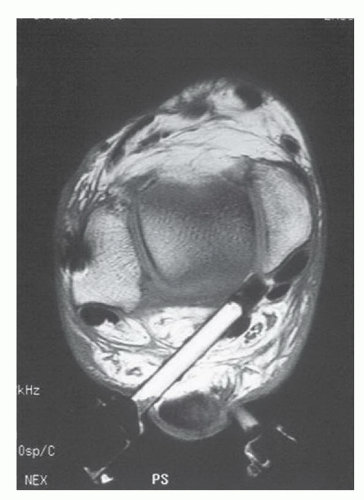

The os trigonum may be found in connection with the posterolateral tubercle (FIG 1). It is completely corticalized and has three surfaces: anterior, inferior, and posterior.

The anterior surface connects to the posterolateral tubercle via fibrous, fibrocartilaginous, or cartilaginous tissue. The inferior surface forms the posterior part of the talocalcaneal joint.

The posterior surface is nonarticular and has the attachments of posterior talofibular ligament, posterior talocalcaneal ligament, deep layer of the flexor retinaculum, and the talar component of the fibuloastragalocalcaneal ligament of Rouviere and Canela Lazaro.30

The tibialis posterior tendon, the flexor digitorum longus tendon, and the FHL tendon situate in their own fibrous tunnels in continuity with the fascia of the deep posterior compartment.

The neurovascular bundles are just medial and posterior to the FHL tendon at the level of the ankle joint, with the tibial nerve as the most lateral structure (FIG 2). Peroneocalcaneal internus muscle, known as a false FHL, can mimic the FHL leading to a potential neurovascular injury.28

PATHOGENESIS

Most cases of posterior ankle impingement syndrome occur in athletes such as ballet dancers or soccer players who have sustained acute or repetitive injuries with the ankle in forced plantarflexion, causing the “nutcracker effect”12,20(FIG 3). Ankle sprain may cause avulsion fracture of the posterior talofibular ligament and secondary impingement.15,21,25,36

Symptoms can be aggravated by any structures localized between the posterior tibial plafond and the calcaneal facet of

the posterior subtalar joint, such as the os trigonum; long trigonal process; FHL tendon; posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament; intermalleolar ligament; and any osseous, articular cartilage, capsule, or synovial lesions of the posterior ankle or subtalar joint.

FHL tenosynovitis is commonly associated with posterior ankle impingement due to the intimate relationship between the tendon and the os trigonum or the trigonal process at the posterior aspect of the talus. This lesion can be an associated injury or secondary to the inflamed surrounding structures.17,27,32

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of posterior ankle impingement is currently unknown. Os trigonum is a benign condition and usually is asymptomatic.

When symptomatic, nonoperative treatment has been found to be successful in 60% of cases. However, Hedrick and McBryde10 reported that only 40% of those successfully treated patients could achieve full preinjury activity levels. The prognosis with nonoperative treatment is generally poor in high-activity patients such as ballet dancers.20

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The routine history should include sex, age, occupation, sports activities, and mechanism of the injury.

Patients should be asked for the description of pain, its location, and any aggravating positions or activities. Pain from the impingement usually is directly posterior or posterolateral to the ankle joint. Pain in the posteromedial aspect may be associated with tenosynovitis of the FHL tendon, which is usually described as pain along the tendon longitudinally. Aggravation of the symptoms with the ankle in full plantarflexion is essential to the diagnosis.

Examination must be performed to rule out other pathologies causing posterior ankle and hindfoot pain, such as Achilles tendinopathy, Haglund syndrome, “pump bump” syndrome, tibialis posterior tendinitis, and peroneal tendon injuries. Diligent palpation of the described structures for pain is recommended.

The physical examination should include the following:

Examination for retromalleolar swelling. Mild swelling occurs in posterior ankle impingement syndrome. Significant swelling should raise the suspicion of peroneal or tibialis posterior tenosynovitis.

Passive ankle plantarflexion. In a positive test, sharp pain or crepitus is produced at full plantarflexion.

In FHL tenosynovitis, pain is produced with active/passive motion of the hallux while a thumb palpates the tendon for tenderness and crepitus. The presence of FHL tenosynovitis should be documented, and it should be treated accordingly.

Tenderness from FHL tenosynovitis is produced with active/passive motion of the hallux while a thumb palpates the tendon for tenderness and crepitus. The presence of FHL tenosynovitis should be documented, and it should be treated accordingly.

Tenderness of other posterior ankle structures. Individual palpation of the peroneal tendons, tibialis posterior tendon, Achilles tendon, and posterior aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity is essential to exclude other pathologies. Palpation of the os trigonum itself is difficult due to its depth. Other diagnoses should be considered if there is no pain with passive ankle plantarflexion and the positive test for other possible lesions in spite of the presence of the os trigonum on radiographs.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A lateral radiograph of the ankle usually demonstrates the osseous lesions sufficiently (FIG 4A). Lateral radiographs can be taken in full ankle plantarflexion and slight external rotation of the limb to visualize impingement from the os trigonum.9

Bone scanning has been reported to identify the symptomatic os trigonum. It is not routinely obtained, however, and does not replace accurate history taking and physical examination (FIG 4B). False-positive results in patients with high activity levels make this study less useful.31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree